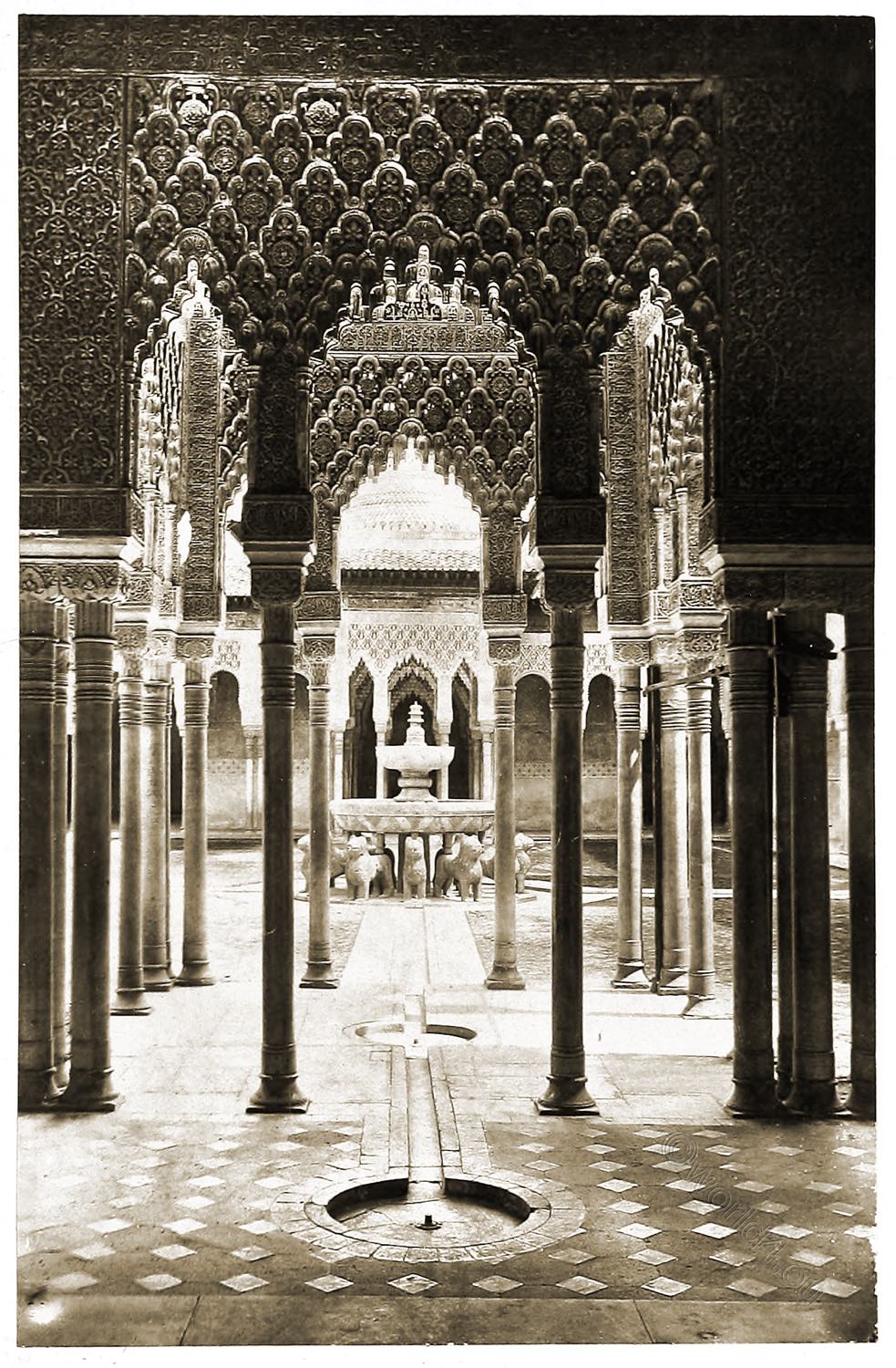

COURT OF LIONS, ALHAMBRA.

ABOUT the middle of the eighth century, when the Moors established the kingdom of Cordova in Southern Spain, they founded the city of Granada. In 1236 this kingdom was brought to an end by Ferdinand III. of Castile, called the Saint and the Holy, and a great part of it was wrested by him from the Moors and annexed to his dominions. That portion which the Moors still held, Mohammed-al-Hamar erected into a kingdom which he called the kingdom of Granada, after the town he selected as his capital; and as soon as he had secured his throne against the attacks of the Christians, his neighbors, he set to work in earnest to beautify the city that he had already fortified.

Close to Granada, on an eminence which commanded it, stood the citadel of the Moorish king. This stronghold bore the Arabic name of “Kal’at-al-hamra,” or the Red Castle, from which, by an easy transition, comes its modern name of the Alhambra. It was girt by a wall more than a mile in circuit, flanked at intervals by roomy towers, and within it, in 1248, Mohammed commenced to build a magnificent palace which it took a century to complete, and which is now called the Casa Real. All that now remains of this superb building, which may be justly called “a poem in stone,” is comprised in two rectangular courts of oblong shape called respectively the “Court of the Fishpond” and the “Court of the Lions.”

The latter, which takes its name from a fountain of marble and alabaster in the centre sustained on the backs of sculptured lions, is shown in the accompanying illustration. The court itself is one hundred feet in length by fifty in breadth; and is surrounded by porticoes, halls, and chambers, supported by light and slender pillars of white marble, which are said to be 128 in number. The apartments which are built around the court are lighted by windows opening on the interior of the court itself, and the reason why the mastermind which conceived and carried out this striking and unique specimen of Moorish architecture, adopted this peculiar mode of construction, is revealed in an Arabic inscription on the walls, which may be thus translated :- “Though my windows admit the light of day, they exclude the view of external objects, lest the beauties of Nature should divert your attention from the beauties of my work.”

The exquisite effect of lights and shadows that prevails throughout the building, the beautiful proportions of the columns and the arches they support, and the elegance of the fretwork and elaborate arabesques with which the capitals of the columns, the cornices, and the faces of the walls are profusely adorned, are conveyed in the illustration, in which the design of the fine marble pavement, and the circular basins by which its uniformity is broken, are clearly shown. The only thing which it fails to convey to the eye of the beholder is the brilliancy of the coloring which is lavished on every part of the building and its ornamentation, and which is but slightly impaired by the lapse of time. The hues and tints that prevail are pink, light blue, and dusky purple, plentifully relieved by gold, and always blended in exquisite taste, and harmonious though most gorgeous.

The Alhambra, carefully preserved by the Spanish government as a work of art, now serves no other purpose than that of a reminiscence of the dead past of Spain, with which times present exhibit a contrast alike unfavorable and deplorable.

Descriptive Article by Francis Young. Photographed by Stuart.

Source: Treasure spots of the world: a selection of the chief beauties and wonders of nature and art by Walter Bentley Woodbury (1834-1885); Francis Clement Naish. London: Ward, Lock, and Tyler, Paternoster Row, 1875.

Continuing

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.