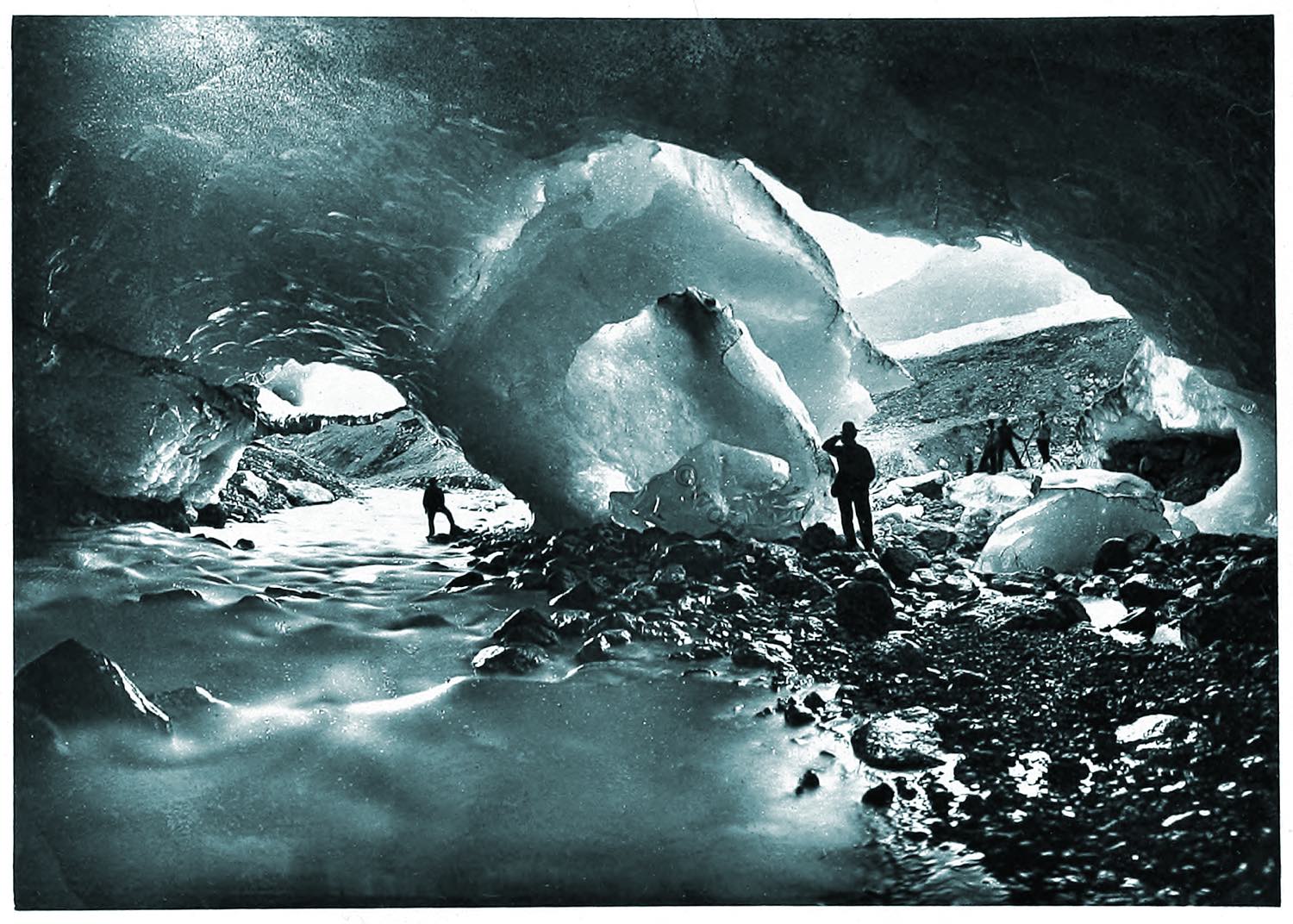

ICE CAVERN.

ONE of the most charming natural phenomena of the Alpine world is the Ice Cavern, or Grotto. Unfortunately for the casual visitor, it is rarely found in perfection, for although every glacier that streams down the mountain side, to melt in the warm air of the valleys, assumes at its extremity an arch-like form, through which the snow water seeks an outlet, it is seldom the structure has the grand and picturesque outline of our photograph. In certain localities, however, where the natural surroundings are favorable, an ice cavern or arch is formed almost every summer, for during the cold weather, be it remembered, all trace of the structure vanishes under the accumulation of fresh masses of ice and snow. At Grindelwald, at Chamounix, at Pontresina, and in other lofty Alpine valleys, year after year, a natural grotto of this kind, fashioned out of solid ice, may be seen.

There are few things that appear more wonderful and fascinating to the traveller than the glittering walls and glassy vault-like roof, as he stands within the cool and sombre retreat. Crystalline pendants of ice sparkle overhead, wherever a ray of sunshine penetrates, and out of the depths of the cavern shines a lustrous blue, as from a thousand prisms. Where a cleft in the ice is deeper than usual, there the colour grows in intensity, until it becomes a gorgeous purple. Big ice blocks, like broken pillars of marble, are scattered in all directions, and from a hidden source foams up the white glacier water, the childhood of a mighty river that here breaks into the sunshine for the first time.

It must be in a fairy palace such as this, that water-sprites have their home, and the beautiful but cold-hearted Lurlines are born, who glide down the dancing rivulet, until, like other water-babies, they attain maturity, and dwell on the Rhine or elsewhere, luring mortals to their death.

Sometimes the locality of these ice caverns is a romantic one, among big rocks and boulders at the very margin of a pine forest, so that from a distance the dazzling white crystals appear in the midst of dark fir-trees. As you peep through a gap in the foliage, or look down from some eminence at the frozen billows streaming through a ravine to the very borders of the wood, it seems to you but an easy walk to the snow-fields. Let not the traveller be deceived, however, for nothing is so illusionary as the proximity of these icy wonders.

Unless the actual distance is known, the traveller does well not to attempt to reach the glacier. Apparently within half-an-hour’s stroll, the tantalising ice pinnacles seem never to grow nearer; mile after mile do you march through the rough pine forest, picking your way over moss-grown boulders and across numberless torrents, until you grow despairing. At last a turn in the path brings you to the edge of the wood, and there is the glacier right before you, only it is probably another mile or two up a wet stony channel before the ice is reached, and this part of the journey it is which is the most tiring of all. Your brief excursion of an hour or so has by this time grown into half a day, and it is evening before you get back again to the comfortable hotel in the village. But the rough scramble over the rocks and rivulets is well worth the trouble, for climbing about and around these grand piles of nature, whose form and beauty are ever’ changing, has a charm peculiarly its own.

Sometimes the icy field is full of rough furrows, with huge white needles and pinnacles of the most fantastic shapes, while elsewhere the glassy surface is only interrupted by deep crevasses, with walls of translucent blue. Above the glacier is a smooth stream of white lava flowing from an adjacent snow peak, but as it descends into the valley the frozen mass breaks up and assumes the forms of spires, blocks, and prisms, and sometimes, as our picture shows, that of a wonderful arch or cavern, through which the snow water passes on its way to feed the broad rivers in the green plains below.

Descriptive Article by H. Baden Pritchard, Author of “Tramps in the Tyrol,” “Beauty Spots of the Continent,” &c. Photographed by Braun.

Source: Treasure spots of the world: a selection of the chief beauties and wonders of nature and art by Walter Bentley Woodbury (1834-1885); Francis Clement Naish. London: Ward, Lock, and Tyler, Paternoster Row, 1875.