Empire français.

The Second Empire.

1852–1870

The kingship of the July Monarchy was overthrown in 1848 by the February Revolution of 1848 and replaced by the Second Republic. Louis Napoleon Bonaparte took advantage of his uncle Napoleon I’s posthumous fame in the presidential elections of 1848 and won the election. On 7 November 1852, he had the title of emperor conferred on him by a resolution of the Senate. Since then he has called himself Napoleon III. In terms of state symbols, the Second Empire drew on the First Empire. France temporarily became the second strongest economy after Great Britain.

This period also saw the modernisation of the cities. Paris in particular was transformed into a modern metropolis under the direction of Georges-Eugène Haussmann by demolishing the old slums and building boulevards and ring roads. Magnificent buildings such as the Paris Opera were built in the city. In two world exhibitions in 1855 and 1867, France confidently presented itself as a leading industrial nation. At the same time, the exhibitions were intended to strengthen the prestige of the emperor.

REIGN OF NAPOLEON III.

1851 TO 1854.

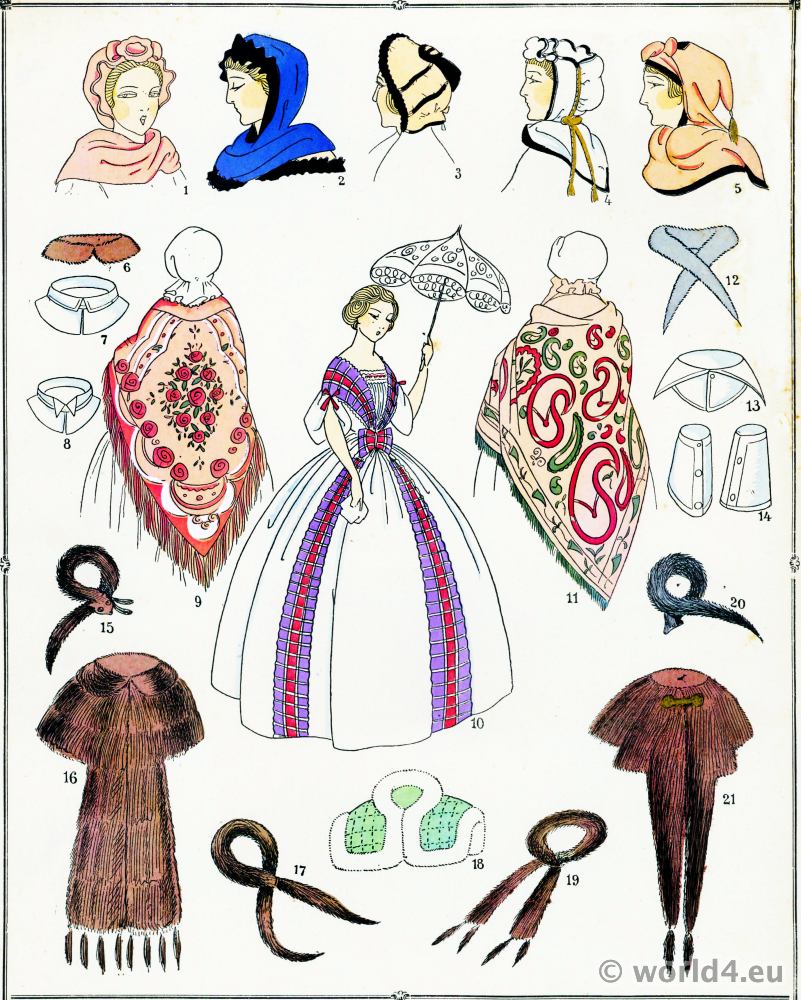

Content: Ready-made mantles – Tulmas, mousquetaires, and rotondes – The Second Empire; reminiscences of the reign of Napoleon I.; Marriage of Napoleon III; dress of the new empress; her hair dressed by Félix Escalier; court mantle and train – Four kinds of dress – Opera dress in 1853-4 – Bodices “à la Vierge,” Pompadour bodices, and Watteau bodices – Skirt trimmings – A new color, “Théba” – Light tints – Social and theatrical celebrities – The Eugénie head-dress and Mainnier bands – End of the first period of Imperial fashions.

The Fashion of the Crinoline.

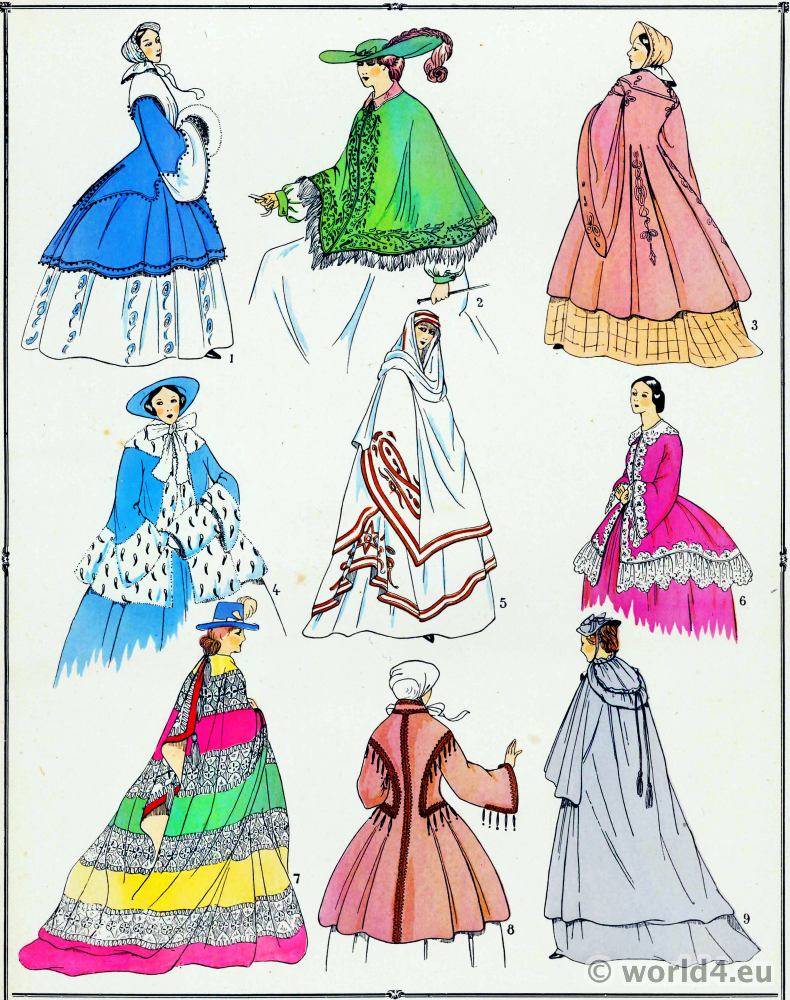

DRESSMAKERS, like tailors, had begun to deal in ready-made garments; and found purchasers for their cloaks, mantles, and trimmed shawls. Special shops were established all over Paris, where customers might make selections from immense assortments of goods. Some of these houses have developed since then into monster bazaars.

A “Talma” was a cloth mantle, with or without a hood, and trimmed in various ways, and was a special favorite with ladies. Some other shapes were extremely simple. Talmas were also called “Cervantes,” or “Charles X.,” or “Valois,” or “Charles IX.”

The Talma clearly derived its origin from Spain. A cloak called “Andromache” was also worn; it recalled the fashions of Greece, and still more the stage triumphs of Rachel. So ineffaceable is the influence of genius!

Next came “Romeos,” “mousquetaires,” “Charles the Fifth’s,” and “rotondes.” Mousquetaires were trimmed with velvet” chevrons,” and were fastened by tabs and large buttons. The others were all shaped like the talma, with a few unimportant variations.

On the establishment of the Second Empire, the fashions of the First were not immediately adopted, notwithstanding the prognostications of certain enthusiasts. We must note, however, that waists became shorter, and that reminiscences of the time of the Great Napoleon were perceptible in some of the accessories of dress, although they took no real root among us. Frenchwomen showed a reluctance to wear costumes that had been severely criticized in their hearing.

Many years were destined to pass by before any attempt should be made to revive the shapes of the First Empire. The marriage of Napoleon III, however, gave a new impetus to feminine fashion, and every woman set herself to imitate as far as possible the style of dress worn by the Empress, now suddenly become the arbiter of attire.

The dress worn by the Emperor’s bride at the marriage in the Cathedral of Notre Dame, was of white terry velvet, with a long train. The basque bodice was high, and profusely adorned with diamonds, sapphires, and orange-blossoms. The skirt was covered with” point d’Angleterre.” This kind of lace had been selected on account of the veil, which it had been impossible to procure in “point d’Alençon.” Felix Escalier dressed the new Empress’s hair. There were two bandeaus in front; one was raised and peaked in the Marie Stuart shape, the other was rolled from the top of the head to the neck, w here it fell in curls that, according to a poet, looked like” nests for Cupids.”

This costume was long the subject of conversation in both aristocratic and bourgeois salons, especially among the adherents of the Imperial Regime.

We must say a few words concerning the court mantle, and the court train, which soon took its place in official attire.

The true court mantle falling from the shoulders was reserved, it is said, for the Empress, the princesses, and some few highly honored ladies exclusively; for the Imperial Court wished to imitate exactly the magnificence displayed by Louis XIV., and the first ranks of Society became luxurious in the extreme.

A court train consisted of a skirt opening in front, but falling low at the sides, and ending in a long train. The train was attached to the waist. Ladies found it necessary to consult a dancing-master in order to learn, not how to advance with a train, which was easy enough, but how to turn round, and especially how to retreat, which was extremely difficult.

Lappets were necessary for court dress; they fell to the waist, and were generally made of lace, and occasionally embroidered in gold or silver.

At full-dress assemblies, elegance and splendor of attire increased day by day; the most brilliant inventions in millinery succeeded each other uninterruptedly.

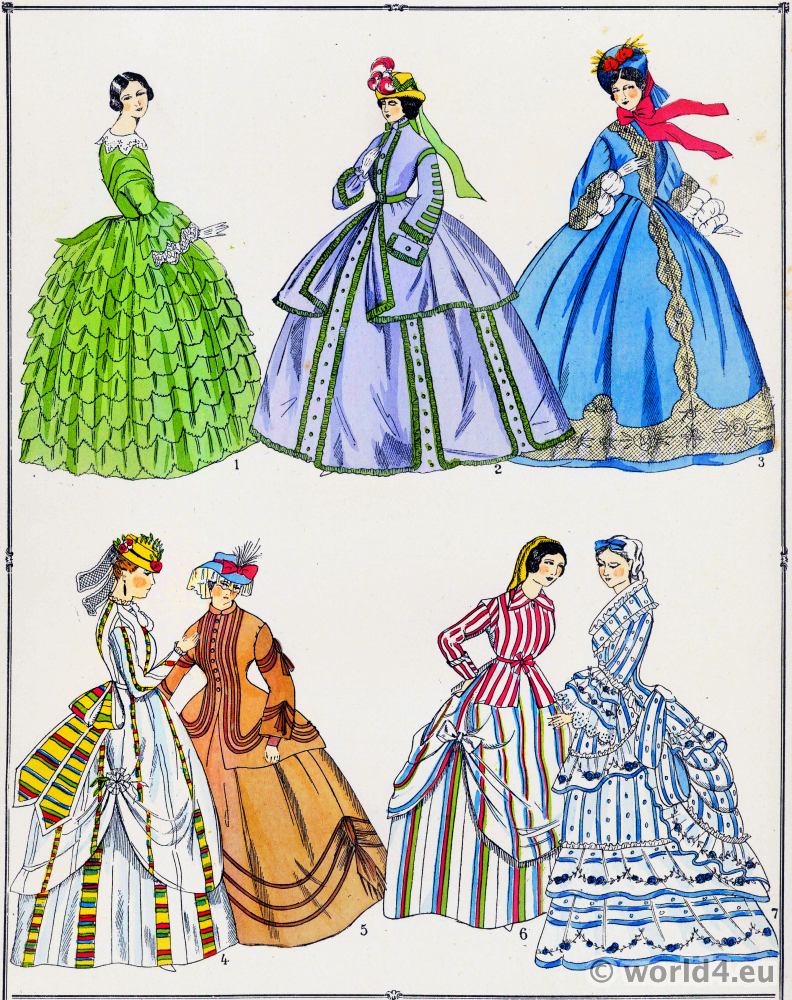

The first dressmakers in Paris were employed in making for the new Empress four series of gowns, if we may so describe them, viz. evening gowns, hall-dresses, visiting dresses, and morning gowns. Among those for” full dress” was one of pink moire antique; it had a basque bodice trimmed with fringe, lace, and white feathers; another was of green silk, the flounces trimmed with curled feathers; and a third of mauve silk, the flounces bordered with Brussels lace. All were made with basques, long-waisted, and either with trains or demi-trains rounded off. The bodices for the most part were draped.

However great the desire of many persons to see the fashions of the First Empire revived, those I have just described were certainly far from resembling them. Although waists were slightly shortened, the general aspect of dress retained the youthful, elegant, and slim effect which has always been, and will always remain, so creditable to the French taste.

The majority of ladies felt no temptation to recall the times of that Maréchale Lefebvre, who was as famous for her finery and feathers as for her singular choice of language and her extraordinary remarks. Nothing of the past can be enduring, except that which has succeeded.

During the winter of 1853-4, dresses were worn at the opera, of which I will describe one as a typical example. The gown was of grey “poult de soie,” the high bodice was fastened by ruby buttons, and the basques, open on the hips, were trimmed with a knot of cherry-colored ribbon. The five flounces of the skirt were trimmed with ribbon of the same hue, laid on flat, and terminating in bows with long ends. This was very unlike the dresses of 1810.

Bodices “à la Vierge,” Pompadour and Watteau bodices with trimmings of lace, velvet, flowers, and ruched, quilled, or plain ribbon, were extremely fashionable. There was a certain grace about them.

On the whole, women greatly preferred the stomachers of the eighteenth century to the short waists of the first years of the nineteenth. They modelled themselves rather on the ancient order of things, than on the commencement of the new order, because above all they sought for pure and delicate outline.

The fashions of the reign of Louis the Eighteenth were resorted to for trimming the skirts of ball-dresses. Large puflings of muslin or lace came almost up to the knees. Here and there little butterfly bows of ribbon nestled in the interstices of the puffs, and produced a charming effect.

The number of new colors was considerable. “Théba” was a brownish-yellow tint, much favored, it is said, by the Empress, and consequently a good deal used by authorities on dress. But it did not remain in fashion longer than was considered desirable by persons always in quest of fresh novelties. Light colors were generally preferred, and every imaginable tint was tried in turn with inconceivable rapidity.

A glimpse of the Empress Eugénie as she drove through the Bois de Boulogne sufficed to set the fair observers to work upon a faithful reproduction of her costume. The toilette at a ball at the Tuileries afforded food for thought during many days to those who had been present.

A few of the court ladies seemed to legislate for Fashion, and sometimes they even competed with their sovereign. Scores of newspapers described the shape and color of their dresses, their jewels, and the flowers or feathers in their hair, and gave minute details of the fete; which they adorned as much by their attire as by their beauty, when they were not tempted into eccentricity.

Only a few actresses of celebrity rivaled the influence of the Empress and her court, especially in the matter of hair-dressing.

The modes adopted by Princess Mathilde, Mme. Espinasse, Mme. de Mouchy, Princess Murat, and the Duchess de Morny, were admired, it is true, but so also were those called Marco-Spada, Favart, Miolan-Carvalho, Doche, Traviata, Biche-au-Bois, Pierson, Cabel, Ophelia, Marie Rose, and Adelina Patti.

One “coiffure Eugénie” was effected by raising and drawing back the hair from the forehead, and arranging it with the aid of the “Mainnier bandeau,” a simple and easily used contrivance. It was only necessary to divide the bandeau into two equal parts, reserving in the middle a small lock that was tightly plaited. This plait was fixed by a comb, and it supported the foundation on which the cc coiffure” was arranged; the firm, puffed-out bands then only required smoothing. With this very few curls were worn. With the help of the Mainnier bands, the Eugenic coiffure formed a roll that increased in size from above the forehead until it reached the ear, where one or two curls falling on the neck completed the arrangement.

Such were the fashions of the first Imperial period, which inaugurated an era of luxury in every rank of society, but did not as yet produce those successive inventions in dress that we shall afterwards have to note, and which are continuously developed in the present generation.

CHAPTER XXVI.

REIGN OF NAPOLEON III. (CONTINUED).

1854 AND 1855.

Contents:

Crinoline inaugurates the second era of Imperial fashions – The reign of crinoline – Starched petticoats – Whaleboned petticoats – Steel hoops – Two camps are formed, one in favor of, and one inimical to crinoline – Large collars – Marie Antoinette fichus and mantles – Exhibition of 1855 – Cashmere shawls – Pure cashmeres – Indian cashmere shawls – Indian woollen shawls – “Mouzaia” shawls – Algerian burnouses – Pompadour parasols – Straight parasols – School for fans – The fan drill – The Queen of Oude’s fans – The Charlotte Corday fichu.

CRINOLINE made its appearance, and revived the era of hoops. It was an ungraceful invention; the crinoline swayed about under the skirt in large graduated tubes made of horsehair.

“Crinoline is only fit,” said a clever woman, “for making grape-bags or soldiers’ stocks.”

This fashion was vigorously and constantly attacked. A lady, for instance, taking her seat in a railway carriage, was compelled to hold her flounces together within the space allotted to her; but a great wave of crinoline overshadowed her neighbor during the whole journey. The next neighbor grumbled naturally, but in suppressed tones, for fear of giving offenze. When the journey was over, very uncomplimentary remarks were passed on the obnoxious garment.

There were several other modes of sustaining the flounces of a gown. Why not adopt starched petticoats, or flounced or three-skirted petticoats in coarse calico?

Horsehair was surely not the only resource for swelling out one’s clothes.

In spite of its opponents, or perhaps because of them, crinoline soon ruled with an absolute sway.

Numbers of women, after holding forth against “those horrid crinolines,” were ready to wear starched and flounced petticoats, less ungraceful indeed than horsehair, but extremely inconvenient. The essential point was to increase the size of the figure, to conceal thinness, and, above all, to go with the stream.

Some very fashionable women invented a whaleboned skirt, not unlike a bee-hive. The largest circumference was round the hips, whence the rest of the dress fell in perpendicular lines. Others preferred hoops arranged like those on a barrel. The most unassuming had their flounces lined with stiff muslin, and the edges of their gowns with horsehair, and loaded themselves with four or five starched or “caned” petticoats. What a weight of clothes!

As for the steel hoops that were soon universally worn, not only were they extremely ugly, but they swayed from side to side, and sometimes, if not made sufficiently long, the lower part of the skirt would fall inwards. Men smiled involuntarily at such exhibitions as they passed them in the streets, but the fair wearers were not one whit disturbed.

The gravest political question of the day was not more exciting to Frenchmen than that of crinoline to Frenchwomen. Two camps were formed, in one of which the adversaries of crinoline declaimed against it, while in the other its defenders took their stand on Fashion, whose decrees they contended must be blindly obeyed. Moreover, crinoline had now become generally worn, and its enemies were acquiring a reputation for ill-nature, prejudice, and obstinate grumbling.

But though swelling skirts retained their pre-eminence in fashion, cages and hoops were gradually succeeded by numerous starched petticoats, and this was a slight improvement.

Crinoline therefore became less ridiculous, but not without a struggle; and it took years to bring about a change that the simplest good taste should have effected after the appearance of horsehair, whalebone, and steels.

During the prevalence of skirts resembling balloons, ladies wore very large collars, to which they gave historic names of the time of Louis XIII. and Louis XIV., evoking reminiscences of Anne or Austria, Cinq-Mars, Mdlle. de Mancini, and the Musketeers.

An immense crinoline and an enormous collar constituted the principal part of a costume. The rest was merely accessory, and was unnoticed on the moving mass for which the pavement of the capital was far too narrow, and which offered a large surface to splashes of mud.

At the same period, Marie Antoinette fichus, either black or white, and trimmed with two rows of lace, were very fashionable; they were crossed over the chest, and tied behind the waist. Black lace bodices were equally popular. Both looked very well over a low dress. Beautiful lace, long hidden in old cupboards, was now brought out and turned to account. Several articles of dress were revived in remembrance of Marie-Antoinette. Besides the fichu, our great ladies wore Marie Antoinette canezous and mantillas. The ends of the canezou finished at the waist, while those of the mantilla were crossed under the arms. Nothing could be lighter or more graceful. Both fichu and canezou found fanatical admirers.

The Empress demi-veils were also a lasting success. Some were made of tulle “point d’esprit,” and edged with a deep blond lace, frilled on; others were of open network, and hardly concealed the face at all.

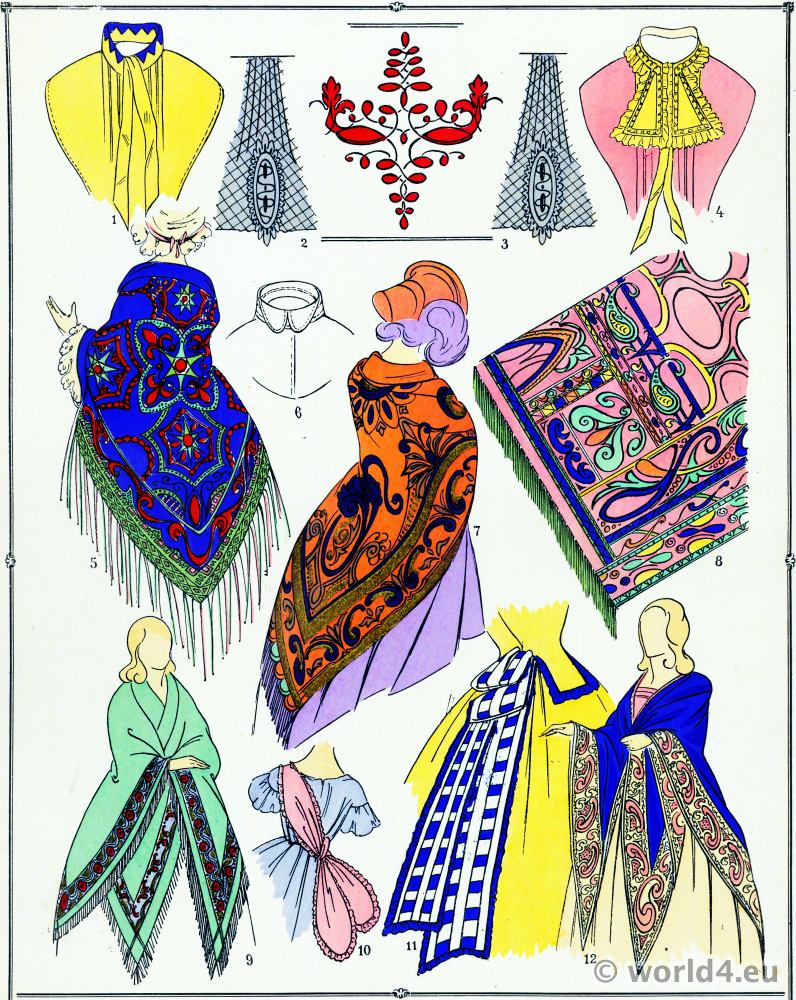

The year following the Paris International Exhibition of 1855, cashmere shawls generally formed a portion of handsome winter costumes. Shawls, even in Ternaux’ time, had not been so universally worn.

In addition to those of India, shawls of excellent quality were manufactured in Paris, Lyons, and Nirnes, and in textures not inferior to those of the East.

The pure cashmere shawls were entirely composed of cashmere wool; the “Hindoo” cashmere shawls were the same as the pure cashmere, with the exception of the warp, which was in fancy silk twisted at the ends; ” Hindoo ” woollen shawls had the same warp as the Indian cashmere, but the woof was of wool, more or less fine in quality.

Towards the end of the summer, as the evenings became cooler, mantillas and basquines were succeeded by “Mouzaia” or “Tunisian” shawls, manufactured from silk refuse, and generally striped in two colors. Some blue and white ones were very pretty, resembling African shawls.

Algerian burnouses with Tibet tassels were greatly used for wraps at theatres, concerts, and balls. French ladies, seen from a distance, looked much like Arabs; but at least their shoulders were protected from the cold, and that was the essential point Burnouses with slightly pointed capes, called “Empress mantles,” were made in plush, Siberian fur, and plaid velvet. These mantles were universally popular; they were worn in France, and throughout Europe, being most comfortable as well as elegant, when gracefully put on.

In the same year straight parasols were succeeded by those with folding handles, made principally of bordered moire antique, and trimmed either with frills of the same, or with fringe.

These “Pompadour” parasols became more and more splendid; they were covered in Chantilly, Alençon, point lace, or blond, and some were embroidered in silk and gold.

They were mostly made of moire antique, and always with a double frill, the edges of which were pinked. Generally speaking, the handles were of ivory and coral. The lace coverings fell gradually into disuse, owing to their liability to be torn.

The handles of parasols for morning wear were generally of cane or bamboo; more expensive ones had handles of rhinoceros horn, green ivory, or tortoise-shell, with coral, cornelian, or agate knobs. The “bourgeoises” were quite satisfied to use such as these when out on household business or paying unceremonious visits.

Parasols with folding handles were soon laid aside, and straight handled ones, worthy rivals of the “marquises” or “duchesses,” resumed their old place. Women of fashion possessed exquisite white or colored moire parasols, lined with blue, pink, or white, with handles of foreign woods, tortoise-shell inlaid with gold, or rhinoceros horn. For country wear they were made in écru batiste, lined with colored sarsnet.

Parasols were now quite indispensable, for in the wide, open spaces of Paris there was no protection from the sun, the trees affording only a delusive shade,

At the same time, fans were in such universal request, especially with young ladies, that it was proposed in jest to found a school of instruction in the art of managing them.

According to the programme proposed for the imaginary pupils, the word of command would be, “Prepare fans,” on which they were to be taken in the hand, and held in readiness. At the word “Unfurl fans,” they were to be gradually opened, then closed, then opened again.

Frenchwomen used their fans as skillfully as Spanish women manoeuvred theirs. A fashionable Frenchwoman knew how to manage very gracefully all the accessories of her visiting or walking costumes, viz. her fan, parasol, handkerchief, smelling-bottle, card-case, and purse.

In 1859 the public was much interested in the fan bequeathed to the Princess Clotilde by the Queen of Oude; it was of white silk, richly embroidered with emeralds and pearls; the handle of ivory and gold was set with rubies and with seventeen diamonds of the finest water.

But, without being equally splendid, many fans of the period were worthy of being classed among works of art. They were exquisitely painted copies of the works of Watteau, Lancret, and Boucher. Since then young girls have learned to paint fans in our art-schools.

One more variation must be noted in the fashions of 1859. The Marie Antoinette fichu was succeeded by the Charlotte Corday, which formed a sort of drapery, raised upon the shoulders, and loosely tied in front. It was principally worn by the “bourgeoises.” In the “great world,” to use an old but conventional expression, ladies preferred the Marie Antoinette; the Empress Eugenie wearing it frequently, as did the most fashionable women of the Second Empire, at varying intervals.

CHAPTER XXVI.

REIGN OF NAPOLEON III. (CONTINUED).

1855 TO 1860.

Sea-bathing and watering-places – Special costumes – Traveling-bags – Hoods and woolen shawls – Convenient style of dress – Kid and satin boots; high heels – Introduction of the “several” and the “Ristori” – Expensive pocket-handkerchiefs – Waists are worn shorter – Zouave, Turkish, and Greek jackets – Bonnet-fronts – Gold trimmings universally used – Tarlatane, tulle, and lace.

FASHION does not assert itself only in the ordinary round of life. It frequently enlarges its domain in consequence of some new custom, or, at least, the development of some old one; and an exceptional occurrence will produce variations in it.

For many years French people had been in the habit of frequenting watering-places, and during the Second Empire the “villeggiatura” assumed extraordinary proportions.

Fashionable crowds hastened to Dieppe, Trouville, Pornic, Biarritz, &c., or to Vichy, Plombières, Bagnères, and other thermal places, on the pretext of health.

But these temporary absences did not emancipate them from the yoke of Fashion. The most fantastic and even eccentric costumes were invented for ladies, young girls, and children, and certain costumes that had been popular at the seaside were worn during the ensuing winter season in Paris.

Casaques, hoods, and capelines found their way from the sea-beach into the towns, where, if not worn by great ladies, they were adopted by the ., bourgeoises” and working-women.

Traveling-bags, for instance, came into general use in France, and were sometimes transformed into dressing-cases.

Extravagance in dress was the rule at watering-places. Ladies walked by the sea splendidly attired in silk gowns, brocaded, or shot with gold or silver. One would have imagined one’s self present at a ball at the Tuileries, or some ministerial reception, rather than at a seaside place of resort. On fine days ladies wore satin spring-side boots, with or without patent leather tips, but invariably black; blue and chestnut-brown boots being no longer in fashion. In the heat of summer, however, grey boots were admissible. High heels were worn, and have since that time become higher still, until one wonders how women will at last contrive to keep their balance.

Generally speaking, boots were made entirely of kid, but sometimes they were of patent leather. The most stylish were partly kid and partly patent leather, ornamentally stitched, and laced on the instep.

To these we must add slippers, shoes with large bows or buckles, and even modern sandals, which, although very elegantly arranged, were only worn by a small minority.

At the time of which we speak, a singular novelty was produced, called the “several,” from the English word meaning many.

A “several” contained within itself seven different garments, and could be worn either as a burnous, a shawl, a shawl-mantle, a scarf, a “Ristori,” or a half-length basquine. Although patented and of moderate price, “severals” did not long remain in fashion. “Ristoris,” in particular, ceased to be worn so soon as the celebrated Italian tragedian whose name they bore, and who had been thoroughly appreciated in France, had left our country.

Pocket-handkerchiefs were round, printed in colors, or with chess-board borders. or hem-stitched, or trimmed with Valenciennes insertion and stitched bias bands. The fashion of expensive handkerchiefs was by no means new, yet never before had they been made with such exceeding care, trimmed with such valuable lace, or so delicately embroidered. It was usual for ladies to embroider their own handkerchief” a task on which they bestowed extreme pains, achieving perfect marvels of patience and art.

In 1859, waists were almost on a sudden perceptibly shortened, and a considerable number of women seemed to fear that fashion was returning to the ungraceful waists of the First Empire-a period which they looked upon as the Iron Age of dress. The style of costume most generally worn that year consisted of a dark green gown with pagoda sleeves, very full, much trimmed, and a wide ribbon sash tied in front. The bonnet would be white and green, with white curtain and strings edged with green, and pretty artificial flowers-particularly daisies, that look like pearls, notwithstanding their golden centers.

The apprehension of a return to short waists was not realized. Good taste triumphed over the incomprehensible whim of wishing to resume former fashions, which had given rise to the adverse and well-founded criticism under which they had previously succumbed.

During 1859 and the following years there was a rage for Zouave, Turkish, and Greek jackets, for “Figaros” and “Ristoris.” Ladies considered them, and still consider them, very comfortable and becoming. They were made in muslin for summer wear, and for the autumn in cashmere or cloth. Some were black, and braided in various colors in the Algerian style, others of different bright shades were braided in black, and some in gold. These jackets were very much worn in the country.

Now it is next to impossible that a jacket should go well with a very short waist, and as jackets were particularly graceful, they certainly helped to maintain the reign of long waists still in fashion at the present day.

Among adjuncts of dress we may mention bonnet-caps, consisting of ruchings or twists, as being very much worn. Nets, also, were extremely fashionable, as they well deserved to be; some were finished with bias bands of velvet, and others with gilt buttons and buckles.

Shortly afterwards, gold began to be used in every possible way; even bonnets were spotted with gold or trimmed with gold buckles. \’alking dresses had gold pipings, bouquets of auriculas were worn, gilt pins with little chains, and frequently large gold buckles.

White Arabian burnouses, shot with gold and silver, were used as opera and ball wraps. Tarlatans were made with diamond-shaped spots of black velvet, having a gold pip in the centre, and tulles with gold stars; tarlatans, also, with gold spots or stripes.

The extremely transparent muslin texture known as tarlatan is of unknown origin-it had an immense success for balls and parties, and is still much patronized by the most elegant women; at the present time it is constantly seen in our salons.

CHAPTER XXVIII.

REIGN OF NAPOLEON III. (CONTINUED).

1860 TO 1862.

Fashions in 1860 and 1861 – Jewellery – Shape of “Russian” bonnets – Nomenclature of girdles – Different styles of dressing the hair – The “Ceres” wreath – Flowers and leaves for the hair – Prohibition of green materials – Anecdotes from the Union Médicale and the Journal de Nièvre – Cloth and silk mantles = Braid and astrakan – Four types of bonnet – Morning bonnets – Artificial flowers.

Now that our task is nearly completed, we might, if necessary, appeal to the recollections of our readers, for we have reached the contemporary era, and we approach the present time.

In 1860, as in 1840, necklaces, lockets, and gold or diamond crosses, suspended by a velvet ribbon or a gold chain, were worn round the neck.

The wealthy wore necklaces composed of separate stars formed of precious stones, or of large gold beads arranged three by three, pear-shaped, and terminating in a gold point.

Some little variations apart, ornaments of this kind have always been conspicuous in feminine dress. The utmost inventiveness of jewelers has only modified the shapes of necklaces, lockets, and crosses.

The same may be said of buckles, watches, watch-chains, buttons, and bracelets; in a word, of all the trinkets successively sanctioned by Fashion.

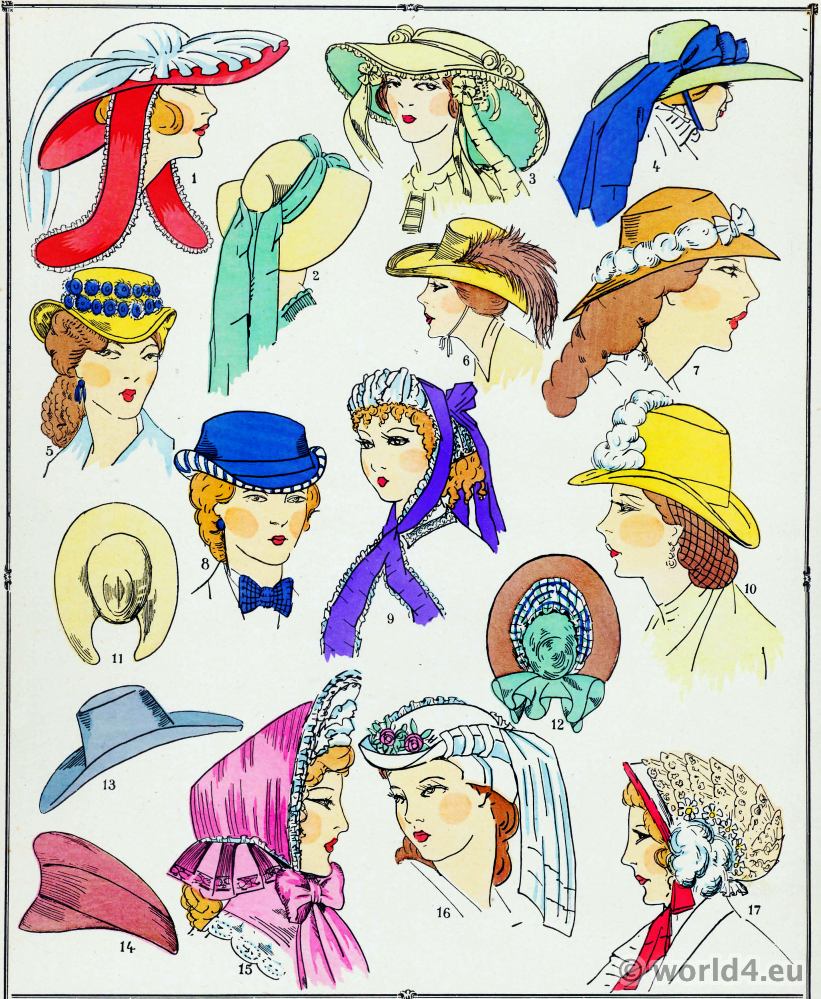

In the year of which we are now writing, the best dressed women, adopted for watering-place wear the Russian hat proper, if I may so style it. This hat was of Belgian straw, high crowned, the brims turned up and covered with velvet, of perfectly round shape, like a plate, and trimmed with a large rosette in front, and an aigrette higher than the crown of the hat.

With that exception, there was nothing new or original in dress. Milliners and dressmakers made certain improvements in small matters, and, as is always the case, in default of new inventions, they endeavored to revive, if only for a very brief period, some of the fashions of the past.

There was a great variety of girdles and belts in 1860, viz.: long and wide ones matching the gown trimmings; long, plain sashes, the ends trimmed with bands of velvet, and fringe; also waistbands in Russian or German leather, hand embroidered, or braided in gold and beads.

In 1861, wide velvet belts called “Medici” were worn, and since that time sashes have become an important article of attire, on account of their forming pout of the national dress of Alsace and Lorraine.

Bands and belts of all sorts seemed to indicate, even at that period, the metal belts that were afterwards fashionable in 1875.

In 1861, bands of gold, either straight or diadem shaped, were worn on the head, and were extremely becoming to dark-haired women. Large gold combs, with a heavy ring to hold the hair, velvet coronets with gold beads or buttons, velvet twists and aigrettes, feather head-dresses, bunches of flowers, velvet bows, and “Ceres” wreaths were very fashionable.

The favorite style of dressing the hair was in very large rolls, with a bunch of berries and ash privet on the top of the head; or a wreath of hops and foliage; or one of oak leaves with gold acorns, and a gold aigrette in the centre. Wreaths of cornflower, with wheat-ears meeting over the forehead, were “Ceres” wreaths. These seem to us to have been among the lust styles arranged with order, and in which the talent of the hairdresser might manifest itself or produce any artistic result.

The fashion of wearing false and dyed hair was about to reappear, and French ladies were to put in practice the axiom, that “beautiful disorder is an effect of art.”

A curious fact attracted the attention of Parisian society in 1861; and the ladies promptly discarded all green materials. In a professional journal, the Union Médicale, the following paragraph appeared :- “A young married lady who had gone to a party, wearing a pale green satin gown, was attacked, after dancing several quadrilles, with sensations of numbness and want of power in the lower limbs, tightness in the chest, vertigo, and headache, and was obliged to return home. The symptoms gradually abated, but the feeling of weakness in the abdominal region lasted until the third day. No special cause, such as tight lacing, &c., could be discovered, and suspicion having been directed to the color of the lady’s gown, a chemical analysis was made, and the presence of a quantity of arsenide of copper detected. It is the opinion of Professor Blasius, that the movement produced by dancing might, especially with dresses of the ample width required by the present fashion, suffice to detach a quantity of the arsenical dye, which on being absorbed by the lungs would give rise to symptoms of arsenical poisoning.”

The Journal de la Nièvre wrote as follows;-

“Some dressmakers living at Nevers had received an order to make a green tarlatan gown. Several strips of the material had been torn off for ruchings, thereby producing a fine dust, which, settling on the face and penetrating the body through the respiratory and nasal organs, had occasioned colic in some cases, and in others an eruption on the face … .”

Green wall-papers and green dress materials were declared to be equally pernicious to health.

An interdict was accordingly laid on green, until some chemical process had been discovered to obviate the dangers described by the Union Médicale and the Journal de la Nièvre.

Women were quite ready to suffer for the sake of their beauty, to tighten their waists, to imprison their feet in shoes too narrow for them, to run the risk of inflammation of the chest by wearing low-cut gowns; but they were not willing to be poisoned by green dyes, especially as green is not a very becoming colour to most women, and by no means sets off the complexion.

In order to withstand the cold of winter, our Parisian ladies made up their minds to wear mantles of soft cloth, or heavy” grosgrain” silk, although the weight of such garments fatigued them.

These mantles were generally trimmed with broad braid; but some of them were literally covered with embroidery, and were consequently very expensive. Real or imitation Astrakan was used for every kind of paletot; the curly coats of the still-born lambs being greatly admired.

Braiding and Astrakan had a long reign; both were constantly used to trim various new shapes in mantles or coats, which they greatly improve without adding to the cost. The town of Astrakan, in Russia, benefited largely by the French fashions in that particular instance.

The following are types of the most fashionable bonnets, with which feathers, or velvet flowers, and rosettes, tufts (called chous), or bows of black lace and white blond, were worn: (1) a bonnet in royal blue velvet, with a scarf of white tulle laid on the brim; (2) a black velvet bonnet, with white tulle scarf put round the crown, and falling over the curtain; (3) a red satin (groseille des Alpes) drawn bonnet, covered with tulle, and with bows at the side; (4) an orange velvet bonnet, with soft crown and white tulle brim, a wreath of flowers on the edge.

For morning dress, horsehair, Belgian straw, and chip bonnets were worn.

Very little change was observable in boots, which were generally made of leather or Turkish satin (satin turc}; shoes, either trimmed or plain, and pumps were no longer in fashion.

Ball-dresses in 1861-2 were generally rose-colored, with an over-skirt of lace, and adorned with flowers. On the head was worn a brilliant bunch of roses, giving a charming finish to the whole costume.

The manufacture of artificial flowers received a great impetus at the Exhibition of 1855; and it is no exaggeration to say that flowers which rivaled Nature itself were produced.

CHAPTER XXIX.

REIGN OF NAPOLEON III. (CONTINUED).

1862 TO 1867.

Sunshades in 1862 – Sailors’ jackets, jerseys, and pilot-jackets – Princess or demi-princess gowns; Swiss bodices; corset or postillion belts – Lydia and Lalla Rookh jackets – Vespertina opera cloaks – “Longchamps is no more” – Bois de Boulogne – Russian or Garibaldi bodices – Paletot vest – Empress belt – 1885 patents for inventions regarding dress are taken out in 1864 – Victoria skeleton skirts; Indian stays; train supporters – “Titian”-colored hair – The Peplum in 1866 – Epicycloide steels; aquarium earrings – Description of a court ball-dress – The fashions of Louis XV., Louis XVI., and the Empire are revived – Sedan chairs – Handkerchiefs at all price.

In our beautiful France, where the fault of the climate is its too frequent showers, it often happened that ladies set out to walk, parasol in hand, with the sun shining brightly overhead, but during their walk a downpour of rain would overtake them, ruin their dress in one moment, and reduce them to utter despair.

I low were such heavy misfortunes to be avoided? How were mortals to contend against the uncertainty of climate?

A remedy was sought and found. Parasol-makers invented the “en-tout-cas,” equally useful in sunshine and in rain; and in 1862 they went a step farther, and manufactured parasols that might have been called “métis,” or half-breeds – that is to say, half en-tout-cas and half sunshade. These were equally useful as a protection against heavy rain or burning sunshine.

And now began the reign of the comfortable; every day the dress and bearing of women became more unrestrained, and less formal.

In 1862, sailors’ jackets, jerseys, and pilot-jackets were not only worn while traveling, or in the country, but also in towns. They were made of light cloth, in English textures, in silk poplin, alpaca, and black silk with much gimp trimming – for gimp is never out of fashion; it is too valuable to the dressmakers, as a means of increasing the amount of their bills.

Simultaneously with the introduction of the fancy garments I have just mentioned, gowns were very prettily made, with bodices either slightly pointed, or with waistbands or long sashes, or else princess shape or del1li-princess. Swiss bodices were also worn, and “corslet” and “postillion” belts.

The above designations need no commentary; the elegant appearance of such costumes can be easily imagined; they were “characteristic,” and not always of French origin. On that very account, perhaps, they were the more successful.

Very many fashions are the result of caprice; hut they are also modes of commemorating some great literary, musical, or dramatic success, or of celebrating some important event.

In 1863, the Fashion journals were loud in praise of the “Lydia” paletot, the “Lalla Rookh” jacket, and the “Vespertina” opera cloak. “Senorita” jackets, in velvet, silk, light shades of cashmere, and cloth, were in great favour.

The ready reception nowadays given to new fashions without waiting, as formely, for certain seasons is easily explained. In 1863 a cry was heard, “Longchamps is no more!” and it is true that Longchamps has ceased to exist. The traditional drive has lost its importance. Only a few tailors and dressmakers, seated in hired carriages, parade their new designs in the broad avenue of the Champs Elysées; poor lay figures, wanting in any kind of ease or elegance. The days are gone when fashionable Paris used to display the newly invented modes on the road leading from the Abbey of Longchamps to the Tuileries; when the Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday in Holy Week were red-letter days in the annals of extravagance ami splendor. At the presce time, the Bois de Boulogne is a constant scene of fashionable rivalry, and is equally crowded in winter and summer, spring and autumn.

Daily drives have thus taken the place of the annual solemnities of Longchamps. The garments that art: most noticeable set the fashion, which is greatly determined by the rank of the wearer. True, Longchamps is dead; but it has been resuscitated in a brilliant and permanent form among the leafy avenues of the Bois de Boulogne.

For visiting dress, in 1863, Frenchwomen gave the preference to white bodices of some thin material; a pink skirt, striped with a darker shade of the same color; a straw bonnet, trimmed with black ribbon and a few wild flowers; a knot of lace at the throat, and some black lace round the wrists.

The most striking of the slight innovations of 1864 were the Russian or “Garibaldi ” bodices of foulard, or of white, reel, blue, or Havana silk, either braided or embroidered in Russian stitch; and the Louis XV. coats and waistcoats, of an English cloth of black and grey mixture. The waistcoats, when not of the same material, were of velvet, smooth cloth, or “gros-grain” silk. The Russian bodices, however, and the coat-waistcoats, were considered too much in “undress” style, and were soon succeeded by further novelties.

Ladies who still wore them, provided themselves with silken “aumonières,” or bags embroidered in jet and suspended by bows of ribbon and lace; and with the Empress or hygienic belt, a small corset made of clastic material, which, when warm, adapted itself to every movement of the body. It was, in fact, the” stays ” perfected.

The quantity of toilet articles manufactured in a single year is really remarkable.

In 1864, the Bulletin des Lois published an edict, by which eighteen hundred and eighty-five inventions patented in that one year were registered. On every page is something concerning dress, viz.: an instrument for waving the hair; steel skeleton skirts, called “Victoria cages,” “corset it jour,” or Indian stays; petticoats for supporting trains, called “porte-trains;” bonnets with faded American creeper, feather parasols, a “transformable and multiple system of clothing,” iron shoes, wicker head-dresses, petticoats with movable flounces, “bijou ” garters, &c.

We must not forget that the year 1864 was famous for the adoption of the “Titian” tresses. Red hair or yellow hair was an ideal eagerly sought after by many ladies, who either concealed their own beautiful dark hair, or dyed it to the desired shade. In a certain section of society there was quite a rage for Titian coloured hair.

There were some quite impossible hues, intended to harmonize with the thickly laid-on paint of the face,-for faces were painted, -just as in the eighteenth century.

Laughter frequently greeted the appearance of these painted idols in places of public resort, but it was quite ineffectual.

An elegant costume, worn in 186 S, consisted of a pearl grey dress, with braidings of the same color, a black belt and silver buckle, and a black bonnet with red ribbons.

The “peplum” of 1866 was formed of a small “corslet,” to which a basque was attached, square in front and at the back, and very long at the sides. This was called the Empress peplum. With this new garment, crinoline was decidedly an anomaly, and its fall commenced. The” peplum,” regarded from that point of view, marks an epoch in history, and deserves our gratitude.

Unfortunately all gowns of heavy material were shaped “à l’Empire.” The skirts were cut straight at the back, and worn with melon-shaped dress-improvers in horsehair. Stiff muslin or a small down cushion was sometimes used instead of horsehair.

One manufacturer invented a petticoat with springs, of which part could be detached at pleasure; another, a transparent parasol; a third advertised his system of aeration for the hair; and a fourth sold notched steels for petticoats, called “épicycloïdes.” There were “aquarium” earrings, consisting of small globes in rock crystal suspended to little branches of water-grasses in enamel; the globes contained fishes. Chains called “Benôiton,” after Sardou’s famous play, were worn below the chin and underneath the bonnet strings, like a curb chain.

The principal Paris newspapers described the dress of Mme. R. K. — at a court ball as follows: “A white gown with alternate bands of tulle and satin; above this a skirt of silver tulle, with wreaths of roses, and spangled with little stars or dots of black velvet; a very long black velvet train edged with satin; a belt of emeralds and diamonds; hail’ dressed ‘à l’Empire,’ and powdered with gold; a knot of black velvet and a diamond aigrette in the hair; no crinoline.”

Yet a few years, and crinoline will be no more. From 1865 to 1867 costumes were worn short, and no longer swept the streets. But shortly afterwards skirts were lengthened again, almost as much as in 1860.

The Louis XV. and the Louis XVI. styles were equal favorites for ball dresses, and they soon became fashionable for walking. Ruchings, kiltings, and plaitings “à la vieille” were much used. The Watteau mantle, with two large box plaits hanging at the back, and the “Bachelick,” with a pointed hood, were both equally popular. The fashionable bonnets were the “Trianon,” “Watteau,” “Lamballe,” and “Marie Antoinette.”

Under the influence of these eighteenth-century costumes, sedan chairs for going to church, or for early morning visits, seemed bound to reappear. Mmes. de la Rochefoucauld, De la Trémouille, De Faucènes, and De Metternich used them; but this was a mere caprice of wealth, and it did not last.

Muffs were small in 1866: the handsomest were of sable tails, and were very valuable. A very small one cost 350 francs. Women who were not rich, or who were of an economical turn, contented themselves with imitation fur, or with Australian marten, Astrakan being now out of fashion. A good many muffs were made of velvet, trimmed with fur or feathers, and as they were essentially useful appendages, they were no longer confined to elegant costumes as formerly; the “bourgeoises” and even the Paris working-women used those of inferior quality, and have continued to do so.

CHAPTER XXX.

REIGN OF NAPOLEON III. (END).

1867 TO 1870.

Five different styles of dressing the hair in 1868 and 1869 – “Petit catogan;” three triple bandeaus – The hair is worn loose – Dress of the Duchess de Mouchy – Refinements of fashion – Various journals – New shades – Crinoline is attacked; it resists; it succumbs – Chinese fashions.

AT this time women indulged more than ever in extravagance in dress, and in the strangest whims of fashion. The minor newspapers published paragraphs describing the costumes of this or that great lady, designating each by her name, by no means to the displeasure of the fair ones thus distinguished. Tailors and dressmakers grew rich.

A very favorite costume consisted of a pink gown, a straw bonnet and white feather, yellow gloves, and pale grey boots.

In 1868-9 the following styles of dressing the hair were fashionable:-

- The hair drawn lip from the forehead in a small “catogan” or club, and a large “coque” or bow of hair above; short curls over the” catogan,” and the same on each side.

- The hair drawn up from the forehead without a parting; a large “coque” in the middle, surrounded by six smaller ones; six long ringlets falling from the back of the head, a little higher than the “coque,” low on the shoulders.

- The hair fixed on the forehead, three immense “coques” on the tup of the head, and ringlets forming a chignon behind.

- The hair drawn straight up from the roots, and forming three rolls falling back wards; a “catogan” and three “coques” underneath; one long “repentir” or ringlet, waved, but not curled.

- Three triple bandeaus in front; a small “catogan” surrounded by three rows of plaits; three large curls behind.

The hair was generally worn high, and dressed in a complicated style, but it was, above all, disheveled. It was frequently worn quite loose and in disorder; less so, however, than in 1875.

The ornamental portions of dress were extremely handsome and expensive. A great deal of jewelry was worn. In 1869, at the Beauvais ball, the Duchess de Mouchy wore diamonds to the value of 1,500,000 francs. Her dress consisted of a gown and train of white gauze spotted with silver; a rather short overskirt of red currant-colored silk, forming a ruched “tablier;” a low, square-cut bodice, and shoulder-straps of precious stones; a sort of scarf of flowers, with silver foliage, fell from one shoulder slanting across the skirt.

At Compiègne, Biarritz, and the Tuileries, by turns, brilliant costumes such as these were seen and admired, and the day after a fete the fashionable newspapers gave minute descriptions of the most elegant dresses, and a guess at their approximate cost.

For many years, and although there was little novelty in the fashions, they never ceased to be the order of the day. More than ever did women make them their occupation, and men also were deeply interested in the subject.

There was, so to speak, a tournament of coquetry in Europe, in which the French ladies always bore away the palm.

New periodicals specially devoted to Fashion were published in France and abroad, and supplied a real want in circles where many articles of dress were made at home.

A taste for handsome dress pervaded every class of society, a “good cut” became every day of more importance, and the smallest variations were adopted, since radical changes were not taking place.

During the Second Empire new colors called “Magenta,” “Solferino,” “Shanghai,” and” Pekin” were produced in much the same chronological succession as the military expeditions to which they owed their names, and which had been successful, indeed, but at a great cost in blood.

Our victories in Italy being thus commemorated by Frenchwomen, they condescended to recall in like manner the capture of Pekin and the famous treaty of Shanghai. The extreme East was to them no longer an unknown land.

A decided change soon took place in the cut of dresses. As had frequently happened before, Fashion went from one extreme to the other; balloons were succeeded by sacks, and tubs by laths.

In 1869, when the question of giving up crinoline was mooted, the leaders of fashion consulted together. One party declared that the reign of crinoline must come to an end on account of its abuses; the other pointed out that “as women now walk so badly on their high heels, crinolines are necessary. and must be retained, because they sustain the weight of the skirts.”

The latter part)’ gained the day at first, and crinolines were merely modified. They were made in white horsehair, with rolls round the bottom and up the back only.

But, after all, crinoline was destined to extinction, were it only because it had already lasted a long time. At various intervals its adversaries had dealt it vigorous blows, and its partisans now began to perceive that it was both inconvenient and ridiculous.

Crinoline could resist no further, and it fell. Dare we say for ever?

Crinoline was succeeded by Chinese skirts, extremely narrow ova the hips, and precisely like those worn by the inhabitants of Pékin (Beijing) or Canton.

The transition was abrupt and sudden. It seemed, however, the most natural thing in the world.

Together with tight skirts, several other accessories of dress

were made as much like Chinese fashions as possible. Up to a certain point French ladies approved of the new style, which has since that time undergone several transformations, the first being the introduction of the poufs and “tournures” (Cul de Paris) that were still worn as recently as four years ago.

Source:

- The history of fashion in France, or, The dress of women from the Gallo-Roman period to the present time by Augustin Challamel, Frances Cashel Hoey, John Lillie. Publisher: New York, Scribner and Welford, 1882.

- Dame fashion: Paris – London, 1786-1912 by Julius Mendes Price. London: S. Low, Marston 1913.

Continuing