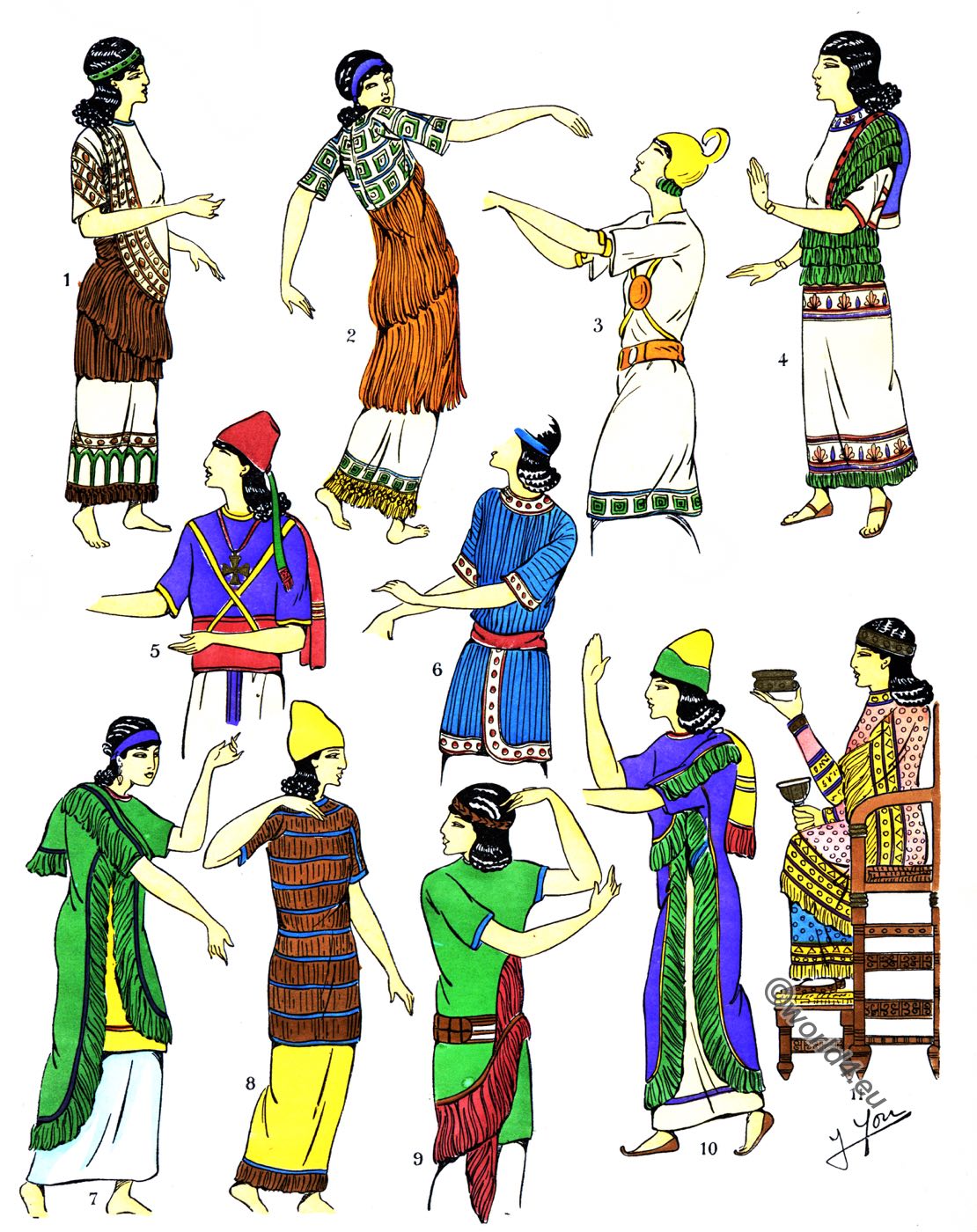

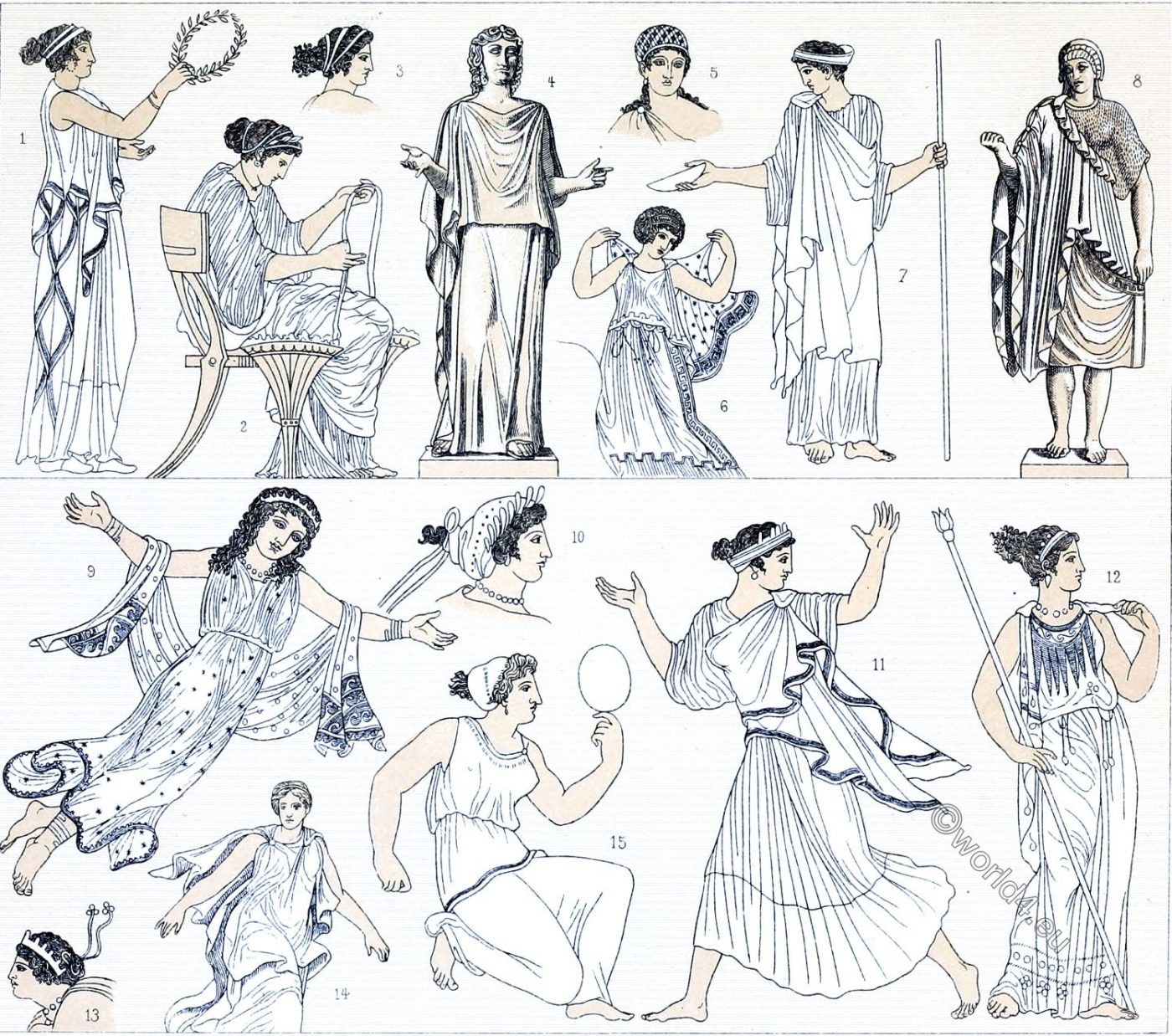

GREECE. WOMEN’S COSTUMES.

Endymata and epiblemata. Fashion of Antiquity.

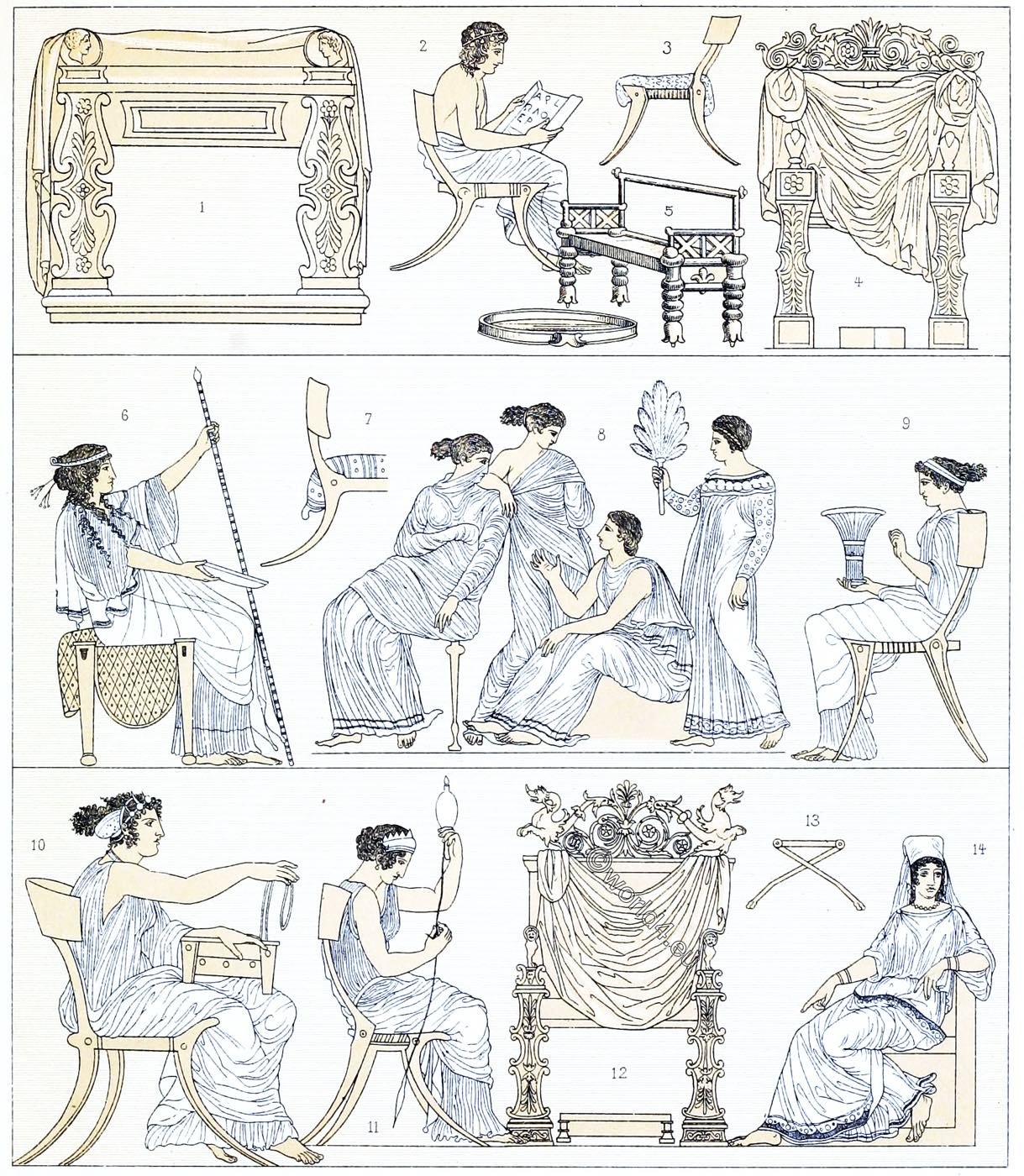

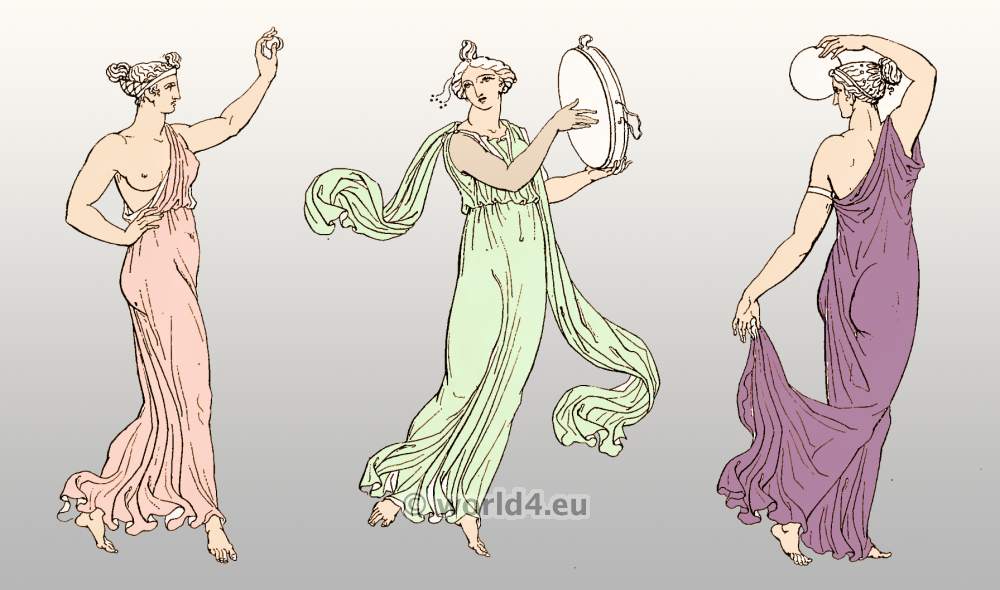

The figures in this panel, which are partly taken from vase pictures and partly replicas of statues, show the various forms of the female costumes customary in the middle period of Greece.

One divided the garments into Endymata 1), which were worn on the bare body, and Epiblemata (coats) 2), which were thrown over it.

1) Endymata or endumata means underwear, i.e. the first layer of clothing worn directly on the body. Therefore Chiton and Peplos are to be regarded as types of Endymata.

2) Epiblemata, literally “outerwear”, were worn over endumata like the chiton. They differ mainly in their structure: while endumata are generally preformed garments attached to the shoulders, epiblemata are simply lengths of fabric wrapped around the body (although they can be fixed with clothing plugs). As these are simple pieces of fabric, it is unclear how different types of epiblemata have been distinguished; it may be the quality of the fabric or the way the garment is draped. As with endumata, epiblemata change over time and according to the sex of the wearer. The most characteristic feature of epiblemata is that as draped garments they offer a greater degree of variability than preformed garments. In addition, Epiblemata, as the ultimate garment, holds the greatest potential for personal communication and presentation. (Source: Body, Dress, and Identity in Ancient Greece by Mireille M. Lee).

The main piece of clothing was the chiton, in Roman times the tunica, a long, folded piece of textile that was wrapped around the body in such a way that one arm was inserted through an armhole on the closed side, while the two upper corners of the open side were stapled together with a buckle or a button on the shoulder of the other arm, the garment was therefore completely open downwards on this side and at the most stuck together at the two lower tips or the open side was also connected by a seam from the hip downwards.

Around the hip, however, the chiton was girded by a band or a belt and its length, which hindered the free movement of the legs, was shortened at will by pulling the garment upwards over the belt. A shirt in our sense was not worn in Greece.

Nos. 1, 9, 12, 15 remind us of the simpler form of the sleeveless chiton. Later, sleeves were added to the chiton, which was made of woolen fabric, soon covering only the upper arm, soon the whole arm up to the wrist.

No. 2, 7, 11. In this shape, the chiton looked like our shirt. Over time, the chiton developed into the double chiton, also an elongated piece of fabric with one and a half body lengths. It was designed in such a way that “the excess of fabric was turned over from the neck downwards over the chest and back, the upper edge formed by the yoke was placed around the neck and the two open corners were nested together on one shoulder, so that the naked body became visible on this open side”.

Beside it there was a semi- and completely closed double chiton (Chiton poderes), which the women wear no. 1, 4, 6, 12, 14. This double chiton was always sleeveless. The flap was called diploidion.

The same was sometimes replaced by the chiton and then served as a short coat (Ampechonion). Figs. 6 and 11 show this shorter type of cloak, while Figs. 1, 2, 9 show the longer Himation and at the same time illustrate the form in which it was draped around the body. The art of draping had to be learned and practiced. In order to facilitate draping, small pieces of lead were sewn into the corners of the Himation.

No 8 (of Etruscan origin) is clad in a coat whose shape was determined from the outset by the tailor and was not left to chance draping. The folds were also artificial. The Lacerna and the Paludamentum (war coat) of the Romans developed from this coat.

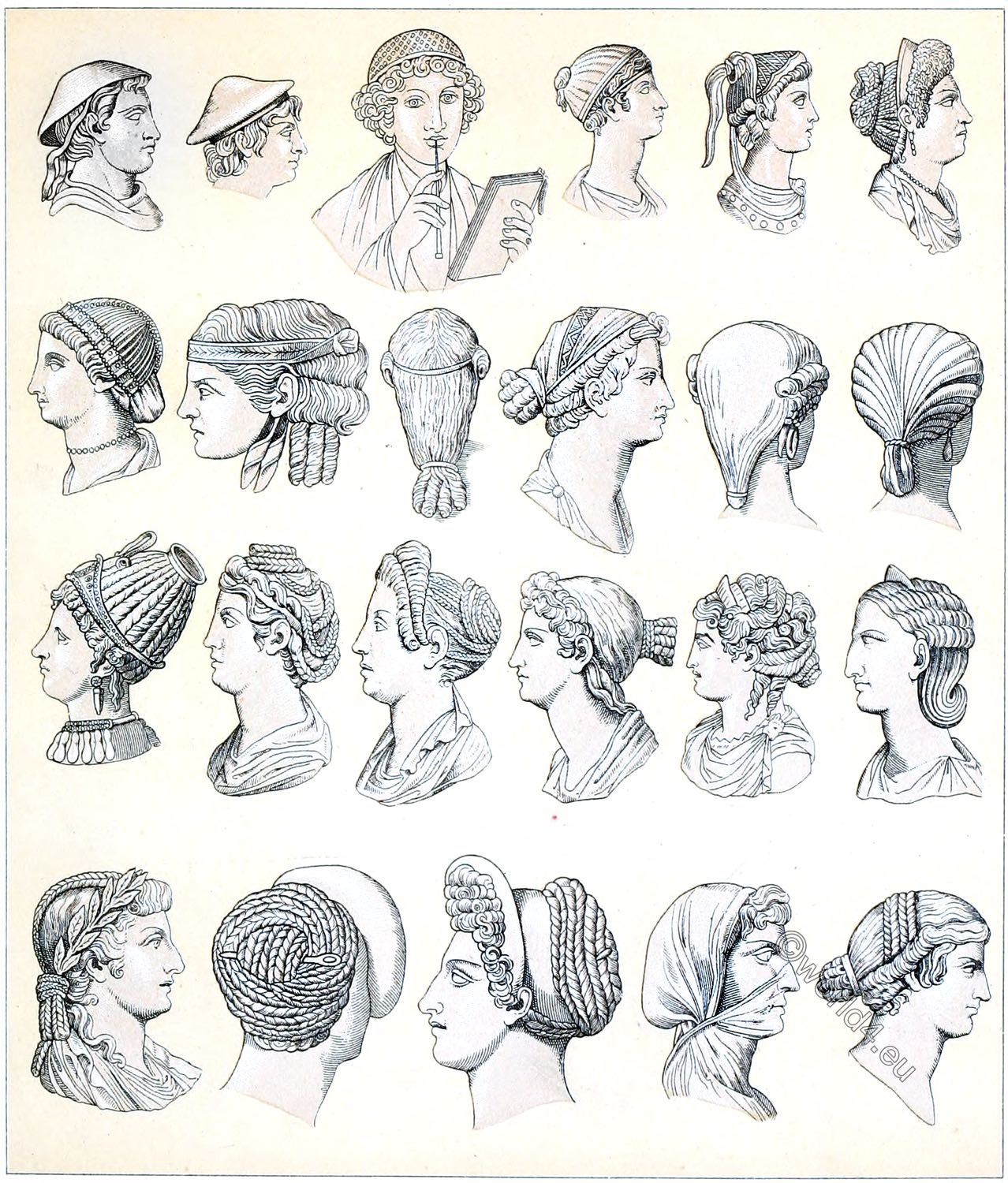

Nos. 3, 5, 10 and 13 are examples of various headdresses, formed partly by hoods and nets, partly by ribbons and headbands.

(After Willemin, Costumes de l’antiquité and Mongez, Encyclopédie méthodique. See also Guhl and Koner, the lives of the Greeks and Romans, Berlin.)

Source: History of the costume in chronological development by Auguste Racinet. Edited by Adolf Rosenberg. Berlin 1888.

[wpucv_list id=”136457″ title=”Classic grid with thumbs 2″]