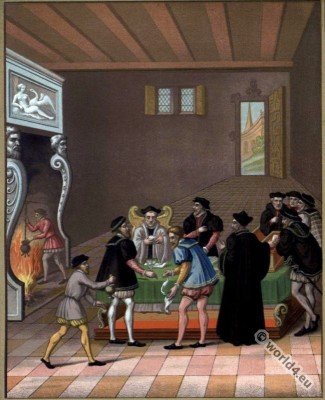

Fashion under the Reign of Henry II. 1547 to 1558.

Table of Content:

Fashions under Henry II. — The ruff — A satirical print of the time —Catherine de Médicis eats soup — The Italian taste — Regulations for dress — Crimson — Who shall wear silk? — Lines on velvet, by Ronsard — Rotond — ” Collet monté ” — Spring-water — Style of gowns and head-dresses — Wired sleeves — Girdles — Caps, bonnets, and hoods — The “touret de nez ” mask worn by women — The ” coffin à roupies ” — Shoes — A quotation from Rabelais.

Henry II (March 31, 1519 at the Château Saint-Germain-en-Laye; † July 10, 1559) was King of France from 1547 to 1559. He came from the dynasty of the Valois-Angoulême.

Henry was married to Catherine de’ Medici (1519-1589) on 28 October 1533, when both were 14 years old. In 1536, after the death of his elder brother Francis, he became heir to the throne (Dauphin) and Duke of Brittany.

On 10 August 1536, the elder brother François died at the age of only 18 years. Thereupon Henry moved up to the immediate position of heir to the throne. During this time he made Diana of Poitiers his mistress, while his wife Katharina did not appear.

Because of the age difference of about 19 years between the young Henry and his older mistress, the relationship is still the subject of speculation. Although Diana could have led a quiet life as a wealthy widow in the province after the death of her husband Louis de Brézé, she returned to the French court for reasons which have not been fully clarified. She cared for Henry, organized his love life and was the unquestionable center of the court. She did not leave the court until Henry died and retreated to her estates. To this day, due to the ambivalent historical and more recent portrayal, she is one of the most controversial and interesting women at the French royal court of modern times.

He was anointed king on 25 July 1547 in the cathedral of Notre-Dame de Reims. Henry’s foreign policy was mainly characterized by wars with the House of Habsburg (Emperor Charles V and his son King Philip II of Spain), which were fought for supremacy in Central Europe and took place mainly on Italian soil

During a joust on June 30, 1559, on the occasion of the celebration of the peace treaty with Habsburg (Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis), a splinter of Count Montgomery’s broken lance stump pierced the visor of Henry’s helmet and penetrated through the eye into his brain. Despite emergency surgery by the best doctors of his time, he died after terrible suffering on 10 July 1559 and was buried in the Basilica of St. Denis.

Fashion under Henry II.

The taste for display had received an irresistible impulse; dress was a fascinating pursuit, and one well adapted to our manners and customs. In the reigns succeeding to that of Francis I. there was neither a reaction, nor any very remarkable novelty. The principal characteristic of feminine attire, however, in the time of Henry II. was the amplitude of skirts and sleeves. Costumes were alternately either of extreme splendour, or of a grave, not to say sombre appearance. It has been observed: “The sixteenth century offers a curious mixture of very striking and of very simple costumes.”

The Ruff.

Catherine de Medicis, the wife of Henri II., who was an Italian, introduced “ruffs” into France. The ruff was a sort of double collar, in stiff goffered plaits. It completely encircled the throat, and sometimes rose above the ears. Ruffs became immensely fashionable, both for men and women. A print of the time proves this. It represents a shop in which three grotesque figures are starching and ironing ruffs. A lady, seated, is having her own ironed, and a gentleman is bringing others. Death is seen on the threshold of the shop, on the right. On the margin there are half a dozen inscriptions in German and French against the fashion of wearing ruffs.

A satirical print of the time.

Beneath the engraving are four German and four French lines, of a highly satirical nature:- “Hommes et femmes empèsent par orgueil Fraises longues pour ne trouver leur pareil; Mais en enfer le diable souffiera, Et à brusler les âmes le feu allumera.”

( ” Men and women out of pride Starch their long ruffs until they find no equal; But in hell the devil will blow (the bellows), And the fire will be lighted to burn souls.”)

Catherine de Médicis eats soup.

Brantôme, the historian (Pierre de Bourdeille 1540-1614, seigneur de Brantome was a French writer in the Renaissance. He gave in his memoirs a vivid picture of French aristocratic society of his time.), relates an amusing anecdote concerning the starched ruffs. He tells us that on one occasion M. de Fresnes-Forget, in conversing with Queen Catherine, expressed his surprise that women should wear such deep ruffs, and affected to doubt that they could eat their soup when thus attired.

Catherine laughed. The next moment a valet handed her a bouillie (Porridge, Mus) for collation. The queen asked for a long-handled spoon, ate her bouillie easily and without soiling her ruff, and then said, “You see. Monsieur de Fresnes, that with a little intelligence one can manage anything.”

The Italian taste.

French ladies copied the Italian fashions in their dress, but with more grandeur and magnificence.

The influence of the Renaissance still prevailed, and art regulated the style of dress to a considerable extent. There was little change in the actual shape of the garments worn, more especially among the middle classes. It became necessary to restrict foreign importation, in order not to crush our home manufactures, and Henri II. also thought it right to issue edicts with reference to propriety of attire, and to the diversity of ranks as indicated by dress. Laws were even passed concerning the quality and colour of stuffs.

Jeanne d’Autriche or Joanna of Austria (1547 -1578) was an Archduchess of Austria, and by marriage Grand Duchess of Tuscany. On December 18, 1565 Johann married in Florence the later Grand Duke Francis I of Tuscany from the Medici House (1541-1587). Their daughter, Marie de ‘Medici (1575–1642) was Queen of France as the second wife of King Henry IV of France, of the House of Bourbon.

Regulations for dress.

Thus, no woman, not being a princess, might wear a costume entirely of crimson; the wives of gentlemen might have one part only of their under dress of that colour.

Maids of honour to the queen, or to the princesses of the blood, might wear velvet gowns of any colour except crimson; the attendants on other princesses were restricted to velvet, either black, or tan viz. an ordinary red, not crimson.

The wealthy bourgeoises, without exception, longed to wear the forbidden material, and thus to vie with the great ladies; but their ambitious desires were necessarily thwarted, and the law only allowed them velvet when made into petticoats and sleeves. Working-women were forbidden to wear silk. This was an extremely expensive material, and women would make any sacrifice to procure it.

Who shall wear silk?

But as we have already remarked, nothing is so difficult of application as a sumptuary law. The wives of gentlemen, of bourgeois, and of artisans were loud in complaint. Then was the lawgiver moved with compassion, and gave permission for bands of goldsmith’s work to be worn on the head, for gold braid as borderings to dresses of ceremony, for necklaces and belts of the same precious metal.

He allowed working-women to trim their gowns with borders or linings of silk; and silk was also allowed for false sleeves, the whole dress only of such costly material was forbidden. But just in proportion as the relaxation of the first rigorous enactments was reasonable and right, so did the authorities show themselves stern and severe towards those women who ventured to transgress the king’s commands.

Lines on velvet, by Ronsard.

Ronsard, *) the poet, exclaims admiringly, like the clever courtier he was:-

*) Pierre de Ronsard 1524-1585, was a French author. Highly esteemed by his contemporaries, then long forgotten, he is now regarded as the most important French poet of the second half of the 16th century.

” Le velours, trop commun en France,

Sous toi reprend son vieil honneur;

Tellement que ta remontrance

Nous a fait voir la différence

Du valet et de son seigneur,

Et du muguet chargé de soye.

Qui à tes princes s’esgaloit,

Et, riche en drap de soye, alloit

Faisant flamber toute la voye.

Les tusques ingénieuses

Jà trop de volouter s’usoyent

Pour nos femmes délicieuses.

Qui, en robes trop précieuses,

Du rang des nobles abusoyent.

Mais or la laine mesprisée

Reprend son premier ornement;

Tant vaut le grave enseignement

De ta parole autorisée.“

( “Velvet, grown too common in France,

Resumes, beneath your sway, its former honour;

So that your remonstrance

Has made us see the difference

Between the servant and his lord.

And the coxcomb, silk-bedecked.

Who equalled your princes,

And rich in cloth of silk went glittering

On his way, showing off the bravery of his attire.

I have more indulgence for our fair women

Who, in dresses far too precious.

Usurp the rank of the nobles.

But now, the long-despised wool

Resumes its former station.” )

Rotond, “Collet monté”.

Starched and plaited linen ruffs, or “rotondes,” were first worn in this reign, also Spanish capes and “collets mounts.“

The proverbial expression, a “collet monté,“ was applied then as now to persons who affected great gravity of manner. It owes its origin to the severity of the Spanish dress, which was adopted in certain quarters in France.

Catherine de Médicis, who deemed it incumbent on her to grieve unceasingly for her royal husband, manifested her sorrow by means of the widow’s dress she habitually wore. Her costume was remarkably austere. It consisted of a sort of cap, with the edge bent down in the middle of the forehead, a collerette with large gofferings, a tightly-fitting buttoned bodice, a wide plaited skirt, and a long mantle with “collet montant,” or high standup collar.

This simplicity of dress on the part of the queen-mother formed an exception to the boundless caprices of the ladies who formed a brilliant court circle around Catherine de Médicis. While confining herself to black, she made no objection to the splendid attire of her companions. Coquetry reached to the highest pitch. The beautiful Diana of Poitiers preserved her beauty by bathing her face, even in winter, in spring water. This heroic practice did not come into general use, notwithstanding its supposed efficacy.

Style of gowns and head-dresses.

The form of women’s attire and head-dresses in the reign of Henri II. was really admirable. There can be no more complicated needlework than that employed on the bodice of a dress as represented in an engraving of 1558. It is trimmed with two little epaulettes, and is made with a basque barely three inches in depth, and far from being “décolleté,“ it is high to the throat, like a man’s jacket (sayon).

Occasionally the fair wearer threw this bodice open, in order to show the pourpoint or vest underneath, and generally it was also slashed either in front or behind, or on the shoulders. By this means it looked less thick, and kept the chest less warm. The sleeves harmonized perfectly with the gown, particularly with the bodice. They were not wide, though ten years previously they had been puffed, but were slashed like the bodice. They diminished in size from the shoulder to the wrist, and were slashed from top to bottom. They were frequently trimmed with beads, and still more frequently with silk riband.

Certain ladies of high birth ornamented them with “fers,” or delicate pieces of goldsmith’s work, not unlike metal buttons. A curious appendage to the costume of the most fashionable ladies, such as we are now describing it, existed; behind the sleeve there falls straight down a false sleeve or “mancheron,” fastened to the epaulette. We have already mentioned these.

The high collerette, detached from the bodice and embroidered or goffered, was attached to a light cambric handkerchief covering the throat, hence its name “gorgias,” from “la gorge,” the throat. When ladies preferred a low-cut bodice, they would wear with it a very large ” gorgias,” covering the shoulders and neck, and of such material as to add to the beauty of the costume.

Skirts were plain, and slightly open in front, A girdle, knotted at the waist, fell gracefully from the peak or point of the bodice, in front, down to the bottom ot the skirt, or was worn hanging from the side, like the rosary of a nun at the present day.

Exquisite lace, imported from Venice, completed the adornment of feminine costume, and made it of immense value. Various styles of head-gear were in fashion, and were worn without distinction by persons in all ranks of society. There were caps, bonnets, and hoods.

The hair was first kept in its place by a little bag called a “cale,” and then the head-dress was put on. Cales remained in use for a long time, and young girls of the class known as “the people” were subsequently called by the name.

The cap was toque-shaped, and generally of velvet, with a white feather over the right ear. The constant movement of the feather, waving in every breeze, produced a charming effect, and conferred on the fair wearers a little cavalier air that poets have frequently sung, and that modern novel-writers have not overlooked. Hats, which seem to have been less generally worn than caps or hoods, were usually of oval shape. They were high with wide brims, and were made in rich materials, or in very fine felt.

Hoods (a favourite head-dress of Catherine de Médicis) were also generally preferred by Parisian women, and were very like those of modern times. They were made of velvet, cloth, or silk, with deep fronts, strings, and a curtain. By a royal edict, velvet hoods were forbidden to all except “the ladies of the court;” on which the bourgeoises ingeniously concealed the velvet under gold and silver embroidery, or a mass of beads and jewels.

The “coffin à roupies”.

The coif suggested the ancient shape of the hood, of which we shall speak hereafter. It was padded, and had a short veil falling down at the back. “For going out in cold weather,” observes M. Jules Quicherat, “a square of stuff was fastened to the strings of the hood, and covered all the face from the eyes downwards, like the fringe of a mask.” This was called either a “touret de nez,” or a “coffin à roupies,” according to the humour of the satirists, whose jests, however, did not prevent ladies from wearing it. We must add that ladies also wore capes with hoods in the severe cold of winter.

Nor must we omit the question of clothing for the feet. This is one of the most important parts of dress, and the woman with the prettiest shoes will generally be found the most graceful in other respects. Ladies wore shoes and slippers, both adapted for indoor wear only, and quite unsuited for the hard stones and thick mud of Paris. In the streets there were but few coaches or litters, and so ladies wore pattens with cork soles, over their shoes or slippers, to protect them from cold and damp.

By Augustin Challamel

Continuing

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.