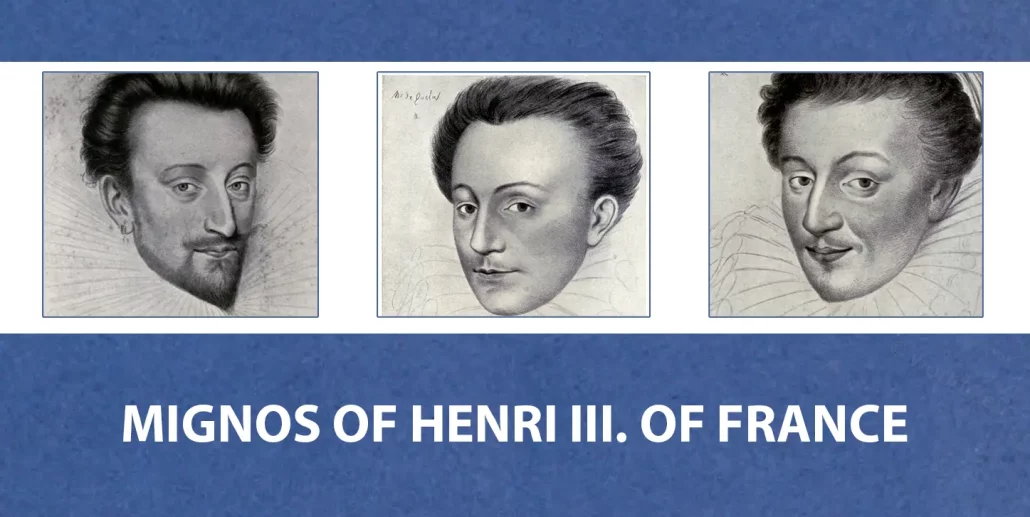

Henry III pushed the high nobility of France out of the affairs of state when they did not cease to fight for power after the beginning of the Huguenot wars. He replaced their members with those of the lower nobility, to whom he gave high tasks and on whom he relied in his government. These young men were not clients of high nobles; rather, their position was based on a loyalty exclusively to the king, to whom they provided unfiltered information. His court was thus a narrow circle of favourites who were able to amass immense fortunes thanks to their master. They came to be called ironically “les mignons”.

Huguenot and League polemicists took it in turns to denounce the king’s favourites and close servants, accusing them of frivolous and “effeminate” morals and even homosexual practices (Henri III’s favourites put on make-up and powder, wore earrings, lace and tinsel).

See also: The Art of Perfumery in Italy and in France.

THE MIGNONS OF HENRI III. OF FRANCE

by Francis Lawrance Bickley

When Henri III., the last of his line, ascended the throne, France had been ruled by the Valois for two centuries and a half. If in that time there were no kings with an undisputed title to be called great, several had high abilities in statecraft, war, or the fields of intellect. Philippe VI., Charles V., Louis XI., and François I. were all, in their various ways, remarkable as men and monarchs; and the race, as a whole, has exercised a fascination over the minds of men such as the Stuarts alone, of all other royal families, have exercised. But by 1574 the best qualities of the Valois were exhausted. Only their vices and weaknesses flourished. Generations of excess had tainted the blood, and the grandsons of François I., three of whom reigned in succession, were a feeble lot. François II., Mary Stuart’s first husband, reigned but two years, and was a child at his death. Charles IX. was a nonentity, whose mother, Caterina de’ Medici, ruled in his stead. His reign is chiefly remembered for the black night of the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre in 1572.

Caterina de’ Medici, for all her vigour, seems to have introduced into the blood of the Valois an Italian softness. Other kings of the house had been lovers of luxury, but they had not that despicable effeminacy which characterised Charles IV., and, in a still higher degree, Henri III.

Even as a boy in his ‘teens, the Duke of Anjou, as Henri was styled during his brother’s lifetime, displayed many of those characteristics which, when he was on the throne, made him the derision of manlier men. He fought with some distinction against the Huguenots at Moncontour *) and Jarnac **); but his chief prowess was with the cup-and-ball and the pea-shooter.

*) The Battle of Moncontour took place on 3 October 1569 during the Third Huguenot War (1568-1570) between the Catholic troops of King Charles IX of France and the Huguenots.

**) In the battle of Jarnac on 13 March 1569, the Protestant army under Louis I de Bourbon, prince de Condé and the royal army under Henri, duc d’Anjou and Gaspard de Saulx, seigneur de Tavannes faced each other near Jarnac in the Charente within the Third Huguenot War. The meeting was remembered above all for Condé’s death.

He was celebrated for his good looks; but his beauty was of a womanish type large round eyes, a shapely nose, a mouth very red and smiling. His dress was exquisite, as his portraits bear witness. Here is a typical costume: a bonnet of crimson velvet laced with gold, surmounted by a white aigrette; a ruff open at the throat after the Venetian fashion; a satin justaucorps; a doublet of white silk; and a little cape of cloth of gold over his shoulder.

Gay, elegant, not without intellectual qualities, Henri was very much in place in the court at the Louvre, where his mother held sway. The life there, a life of amorous intrigue, of soft pleasures and silken scandals, suited his temperament. He himself was immensely in love with the Princess of Condé, and pressed his suit, it appears, with no small success. Consequently he showed little elation when, at the beginning of 1574, he was offered the elective crown of Poland. He would far liefer have been a duke in Paris than a king in the cold north.

Go he must, however. The ambitious Catherine de’ Medici was not going to forgo the satisfaction of seeing another of her sons with a crown on his head ; and at that date there was no great probability that Henri would ever be King of France. Charles had just taken a wife, and was expected to beget an heir. The Huguenots, indeed, who hated Anjou as one of the most extreme of the Papists, wished to make his acceptance of the Polish crown a bar to his succession to the French. Catherine, however, would put no such disability on her favourite son, and it was an understood thing that if Charles should die without male offspring, Henri should reign in his stead.

With this problematical chance of ever again knowing the gaiety of the Louvre and the graces of the Princess of Condé, the young prince had to be content. His departure from Paris was celebrated with festivities. All over the town his cipher as King of Poland was to be seen. Balls, masquerades, and all kinds of entertainment were given in his honour.

At the Tuileries there was a magnificent banquet. Emblematic pictures of Catherine de’ Medici and her two sons were exhibited: the queen-mother as Pallas Gallica, a morion on her head, a buckler, emblazoned with the Medusa, on her left arm, and a halberd in her right hand; Charles IX. as Jupiter the Preserver; Henri as Apollo Gallicus, with lyre, quiver, and arrows. After these celebrations, the new king set out on his journey, accompanied as far as the frontier of Germany by his mother and brother.

Henri chose to consider Poland a place of exile, but it was an exile of a very tempered sort. From the first he was popular with his subjects. Sons of the stern north, the Poles looked with admiration on this crimped dandy from the south whom they had chosen to rule over them. And if the king was likely to find few kindred spirits in Cracow, he was not companionless.

At the Louvre he had gathered round him a group of young men of tastes similar to his own, who were ready to bear him company in his pleasures, follow his fashions in dress, give him countenance in his love-making. These were the celebrated ‘ whose ascendency when Henri came back to France as king did much to make his reign anathema to sober historians.

It says a great deal for the affection of these young men towards their master that they were ready to leave the delights of Paris and follow him into this wild country, whence, perhaps, he might never return. All of them had mistresses in France, for the most part among the maids-of-honour of Catherine de’ Medici, and though they were soon seeking present consolation among the ladies of Poland, theoretically, at any rate, they were faithful in absence. Every week couriers rode post from Cracow and Warsaw to the French capital bearing passionate protestations, sometimes written in the blood of these extravagant youths, and then rode back to cheer the hearts of the exiles with desired replies.

One day, towards the end of 1574, a letter of more serious import came to the king. Charles IX. was dead, and Henri was heir to the throne of France. It is improbable that he spent long in mourning his brother. He wished with all his heart to be back in Paris, and he at once published his accession in the streets of Warsaw, sent letters constituting his mother queen-regent until his arrival, and began preparations for his journey.

The Poles, however, were not going to let their king desert them without a struggle. They were in love with him and the bright French courtiers, whose ways they strove to emulate, and they announced their intention of retaining them by force. So Henri was reduced to the somewhat undignified course of a surreptitious flight from the land over which he was the lawful ruler.

The Sieur Pibrac (Guy Du Faur, Seigneur de Pibrac 1529–1584, French jurist and poet), a counsellor of the king and a man of resource, was the leading spirit in this adventure. On an October night, in the midst of a thick fog, he conducted the French court silently out of Cracow. Once clear of the city, the fugitives made for the German frontier, hoping to reach it before their flight was discovered. Pibrac himself, who, with some others, stayed behind to cover the retreat, very nearly fell into the hands of the infuriated Poles, who, as soon as they discovered that their king was missing, turned out in a body to catch him. The unfortunate counsellor had to hide for some time in a reedy marsh, and presented himself to Henri covered with thick, black mud, much to the amusement of the mignons.

Henri and his friends made their way to Vienna, where they were honourably received by the Emperor Maximilian, father-in-law to Charles IX. By him they were warned against taking the direct route across Germany, which would have entailed a perilous passage through the domains of Protestant princes. Acting on his advice, therefore, they turned southwards, and crossed the Alps into Italy, intending to reach France by that devious but safer route.

Once in Italy, Henri felt the call of the land which was half his own. Anxious as he had been to hurry home and to claim his crown, he could not resist the lure of Venice. His arrival in Paris was delayed several weeks.

The Republic, then in the heyday of its glory, gave him a reception which put any Parisian pageant in the shade. The Venetian love of colour, which Titian and Veronese have immortalised, made the carnivals of the city of canals sumptuous beyond imagination. And Henri’s stay there was one gorgeous carnival. It is no wonder that, with his ardent love of all luxury and beauty, he should, for this, have been content to delay even the state entry into his kingdom.

Catherine de’ Medici met her son at Avignon, where, with that extravagant piety which was the natural complement of his profligacy, he was received into a brotherhood of penitents, and took part in their mortifications. He was anointed king at Rheims.

As King of France, Henri did not abandon the boon companions who had shared his earlier amusements at the Louvre, and lightened his two years’ exile in Poland. On the contrary, he added to their number. He surrounded himself with a crowd of young men, of noble birth, for the most part, but whose chief qualifications were good looks and tastes similar to his own. They did not aspire to high military commands or posts in the state, these favourites of the early years of the reign. Their duty was to amuse their king and themselves. They did, therefore, little direct harm to the country at large, such as has been done by favourites invested with great power. Nevertheless, they soon became unpopular.

Their extravagant effeminacy, their quarrelsome habits and loose morals did not

commend them to simpler and manlier folk. “About that time” writes Lestoile, “the mignons began to be gossiped of among the people, to whom they were very odious, because of their unruly and arrogant ways, the effeminacy of their habits and the enormous gifts which the king bestowed on them. These exquisite mignons wore their hair long, frizzed and curled up round their little velvet bonnets, in the manner of women, and frills of linen half a foot in length which made their heads look like John the Baptist’s on a charger. … Their recreations were to gamble, blaspheme, leap, dance, fence, quarrel, and wench, and to follow the king anywhere and everywhere; to do nothing and to say nothing except to please him.”

To give them and Henri their due, however, there were more admirable elements in the company of the mignons. None of them lacked courage, and some were too good for their position. Gilles de Souvré, Marquess of Courtenvaux, for instance, who was one of those in Poland, fitted better into Henri IV.’s reign than Henri III., and under the first of the Bourbons rose, by sheer merit, to be a marshal of France.

The use Henri III. made of his gallant companions is well illustrated by the following anecdote. When at Lyons, he cast the eye of desire on the wife of a distinguished citizen. Balzac d’Entragues (of whom more anon) and the Count of Maulevrier were commissioned to obtain the lady’s complaisance. That was easily done. The difficulty was to square the husband, who was excessively jealous, and followed his wife like a shadow. An appeal was made to his reputed avarice. A voyage that might have been much to his profit was suggested, and rejected. Then his desire for honour was attacked. He was offered a commission to visit certain Hanseatic towns on a diplomatic errand. Even this bait was refused. Finally, a subtler ruse was employed. The two courtiers went to the man’s confessor, who was also head of the Franciscans in Lyons, and asked him how it was that so prominent a citizen disdained to belong to the Brotherhood of the Penitents, of whom the king himself was a member. Finding the confessor had reasons to offer, they boldly threw off all disguise, told him what they wanted, and begged his assistance. The Franciscan proved a loyal subject.

The next day a procession of the Penitents was held, in which the unfortunate citizen, as the newest professed, had to carry the cross. The king and Maulevrier, who were also in the procession, seeing their victim fairly started, slipped away to their assignation. The new Penitent, however, was by no means happy. His suspicions were aroused, and when, on passing near his own house, he thought he saw the shadow of a man’s hat in a window, he nearly dropped the cross. So overcome was he that he had to be carried out of the procession. He was borne homewards, accompanied by a crowd of friends and relatives. And while, in one room, he was being restored by the ministrations of his dutiful wife, in another the king was hastily getting into his Penitent’s dress, wherein he eventually rejoined the procession unnoticed.

Such enterprises as these were hardly likely to render the mignons popular. Nor was indignation against them confined to honest citizens. Their conduct made them odious to men in higher places than the poor burgess of Lyons. Nothing delighted them more than to stir up strife. They assailed with their seductions the wives of the greatest. They quarrelled interminably with those who were not of their circle.

Naturally enough vengeance was sworn and taken. Duels and ambushes were frequent. It was an age when you killed your enemy without being too nice as to the method. Gaps soon began to show in the ranks of Henri’s young men.

The first of them to come by a violent death was Louis Beranger du Guast (c. 1540 – 31 October 1575), one who, whatever his vices, had no lack of manhood. He had been longer than any of his colleagues in the royal favour. In 1574 he negotiated Henri’s marriage with Louise de Vaudemont. Then, quitting for a time the life of pleasure, he joined the Duke of Guise, who was campaigning against the Huguenots. His bravery was conspicuous at the battle of Dormans, where Guise got the wound in his face for which he was ever afterwards known as Le Balafré. After this victory Du Guast returned to the court. He had done better to have stayed among the slain at Dormans.

There must have been something in the atmosphere of the Louvre which made dubious and perilous intrigue irresistible. Du Guast had not been back from the wars many days before he was in the thick of a discreditable scandal. A zealous Catholic and follower of the Guises, he hated the king’s brother, the Duke of Alençon, who had Protestant leanings. And like others of the mignons, he specially detested the duke’s favourite, Bussy d’Amboise, le brave Bussy, the brilliant swordsman of Dumas’s La Dame de Monsoreau. Now Bussy occupied the position, charming but by no means unique, of lover to the beautiful and large-hearted Marguerite, sister to the king and the duke, and wife to the Huguenot Henri of Navarre. Du Guast must needs signalise his return to court by ferreting out and exposing this amour.

Every one concerned was terribly upset; but it was Marguerite and not Bussy who had to bear the brunt. Her brother, her mother, and her husband heaped reproaches on her pretty head. She vowed to be revenged on the author of her discomfiture. The manner of her vengeance was characteristic.

In the convent of the Augustines at Paris a certain Baron de Vitteaux was lying in hiding, because of a murder he had committed four years previously. Now Marguerite knew that the chief opposition to Vitteaux’s pardon had come from Du Guast. She went to the convent. Her errand was extremely reasonable. She had a grudge against the minion, and so had Vitteaux. Why should not Vitteaux aid her in doing away with this common enemy? The baron hesitated at first, but Marguerite, putting forth her charms, at length won him to do her will.

Du Guast had, in the Rue Saint Honore, near the Louvre, a little house, which had commended itself to him by reason of its unobtrusiveness. It had struck him as a good place for secret assignations, an important consideration to men of the minion breed. Thither, at ten o’clock on the last night of October 1575, accompanied by a number of hired assassins, came the Baron de Vitteaux. They found Du Guast in bed, and, while some put out the lights, others cut his throat. Then they made a holocaust of the unprepared servants and departed.

The outrage was, of course, discovered on the following day, and Henri commenced proceedings against Vitteaux, who, letting himself down from the city walls by means of a rope, had taken refuge with the Duke of Alençon. The matter was not pressed, however. Henri did not feel inclined to embroil himself with his brother. For some time Du Guast had not stood so high as formerly in his favour. He was of too energetic a nature to be wholly pleasant to the king, whom he had had the bad taste to urge to a manlier course of life than he cared to pursue. So Henri contented himself by giving the murdered man an expensive funeral, and then turned to the living. Among these none stood higher in their master’s favour than the handsome Jacques de Quelus, scion of an ancient and distinguished house of the Languedoc, and the equally well-born François de Maugiron, whose father, the Baron d’Ampuis, was lieutenant-general of his native Dauphiné.

Maugiron was remarkable for the fact that he had lost an eye at the siege of Issoire. This misfortune was the theme of a sonnet by Ronsard, who, by the way, describes the left eye as missing, though in the favourite’s portrait the empty socket, over which the quaint little cap droops, is on the right side. At one time he was a minion of the Duke of Alençon’s, but for some reason grew dissatisfied with that service. He then joined Henri and, since none is so zealous as the convert, threw himself with energy into that campaign against the duke and his followers, which was the principal occupation of the king’s turbulent favourites.

For Du Guast was not the only one to bear animosity against Alençon. Maugiron, who had been his servant, Quelus, who had never served him, but had been in Poland with Henri, were a like against him. And, as in Du Guast’s case, the victim of their malice was not the duke himself, but Bussy d’Amboise. They, too, charged him with being Queen Margot’s lover, though this quarrel was at its height two years and more after Du Guast’s exposure had met its prompt reward. Bussy answered with mockery at the effeminate fashions of his enemies. It was no unusual occurrence for Henri and his mignons to don female garb, making themselves fair game for the derision of such virile swashbucklers as Bussy d’Amboise.

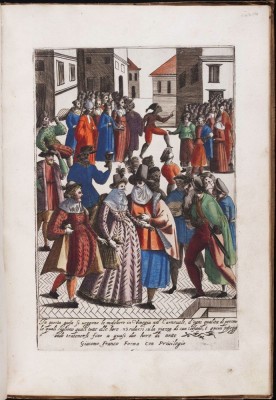

On Twelfth Night – le jour des rois – in 1578, Henri, following the old custom, led the Queen of the Bean *) from the Louvre to the Bourbon Chapel, where Mass was to be said. Both the king and his mignons were frizzed and bedizened even more extravagantly than usual. Alençon was also at the service with his suite, including Bussy d’Amboise, who, though attended by half a dozen pages in cloth of gold, was himself clad in his usual quiet style. Looking at the gay company around him, he flung out a scornful remark which he took good care should be plainly heard.

*) The Queen of Beans, also known as the “Queen for a Day”, celebrated the Feast of Epiphany around 8 January, held at French Court by King Henry. The bakers hid a bean in a cake and the one who found it “ruled” as temporary Queen over the festivities that comprised the Epiphany.

One night, not long after this, twelve hired assassins sprang on and killed a servant who was walking with him. Bussy saw at once that the men had missed their quarry, guessed that they would soon discover their mistake and would set about repairing it. Fine swordsman as he was, he was no match for twelve. Slipping into a doorway which stood half open, he despatched a messenger post haste to his friend Crillon, who came with six armed men and conducted him safely to his own home.

After this incident, Bussy was not seen at court for some time. His absence, however, did nothing to heal the breach between him and the favourites, and as soon as he returned their quarrels broke out afresh. At length Henri determined to interfere. Summoning Quélus and Bussy before him, he said that he desired to see them reconciled there and then. Turning to his brother’s favourite he bid him embrace Quélus.

“Only that, sire”? replied Bussy. “If you please, I will kiss him. I should be delighted.” Suiting the action to the word, he embraced his enemy in so exaggerated a manner à la pantalonne, says the Queen of Navarre that the assembled courtiers could not repress their laughter.

So the king’s efforts as peacemaker utterly failed. Two days after the scene just described, Quélus and M. de Beauvais-Nangis, a minion, with two others, saw Bussy d’Amboise, who was coming from the Tuileries. He was riding a fine Spanish horse, we are told, and had with him a certain Captain Rochebrune. Coming thus upon his enemy, Quélus, forgetful of the recent reconciliation, doubtless, under the memory of Bussy’s smarting, buffooneries, set on him with his companions, four against two.

At that time Henri, then Duke of Anjou, was hand and glove with the Duke of Guise. In politics and in pleasuring their tastes were similar. They were ever in one another’s company, and Anjou saw much of his friend’s young protégé. He found him after his own heart. For Entraguet was growing up handsome, brilliant, and extravagant. His predilections were rather wanton than warlike. He loved the boudoir better than the battlefield. There was nothing Henri cherished more than a good causeur, and Entraguet’s tongue was both witty and scandalous. It was not long before a transference was made, and the youth passed from the service of Guise to that of Valois.

Charles de Balzac baron de Dunes, known as Entragues (c. 1547 –c. 1599), was in an age of gallants, notorious for his gallantries. He is said to have wooed the Duchess of Retz with success; and, like Bussy d’Amboise, he is numbered in the goodly company of the lovers of Marguerite de Valois. According to the scandalous Divorce satirique *) he was the first of them all, but it is probable that he must yield place to the Duke of Guise, who won Margot’s favour about 1570. If Balzac succeeded his old patron, his term of bliss cannot have been long. In 1572 the princess was married to Henri of Navarre, and the courtiers sought oblivion in Poland.

*) Le Divorce satyricque is a violent satirical attack on Marguerite de Valois, written to justify Henry IV’s divorce from the princess.

Three years later, however, if scandal may be believed, negotiations were renewed. Entraguet was lying sick at Lyons, and Queen Marguerite was one night seen going stealthily to his lodging. This fact came to the ears of Quélus and Du Guast, both of whom hated Balzac as a dangerous rival. They at once hurried to the king with their news, and so successfully poisoned his mind against his old friend that le bel Entraguet never again stood in the front rank of the mignons. For a time he remained of their number, but it was not long before he had left them altogether.

One cause of his defection or disgrace was probably political. The friendship which the Duke of Anjou had shown for the Guises was not continued by the King of France. The house of Lorraine was the centre of the extreme Catholic party, and the soul of the recently formed Henri, on the other hand, had receded somewhat from his zeal of the days of the Bartholomew. The Guises accused him of lukewarmth in the cause, while he saw in the popularity of the Duke of Guise a menace to his own authority. Nor was he wrong; but that is later history. Meanwhile, Balzac d’Entragues had shown that his sympathies were with his old master.

The exact cause of the great duel is unknown. There was never, certainly, any love lost between Quélus and his former colleague, but there must have been some special impulse to this climax. Lestoile *) speaks of a trivial quarrel which had sprung up at the Louvre the day before the combat. That queen of misrule, Marguerite of Navarre, incensed at the treatment accorded to Bussy, may have had a hand in it, though it seems scarcely probable that even she would have induced one lover to fight the battles of another. But it was an age when many things were possible.

*) Pierre de L’Estoile (1546 – 1611) was a French jurist, writer and chronicler. L’Estoile’s diary-like notes are one of the most important sources on French history under Henry III and Henry IV.

Whatever the cause, on Sunday, 27 April 1578, at daybreak, six gentlemen gathered at a quiet spot at the end of Rue Saint Antoine, near the Bastille. Quélus brought with him Maugiron and Livarot, another of the mignons. Entraguet’s seconds were Ribérac and Georges de Schomberg, a lad of eighteen years, brother of Gaspard de Schomberg, the sage and celebrated councillor of Henri IV.

A dispute arose between the principals. Quélus complained that Entraguet had a dagger, while he had none. “The more fool you to have forgotten it” replied Entraguet. “We are here for fighting, not for punctilios.” And he refused to forgo the uses of his own dagger, as would have been done in a more chivalrous age. So Quélus fought him at a disadvantage, and got his left hand slashed to ribbons with fending his adversary’s blows.

As Brantôme laments, no one witnessed the duel but three or four poor people, certes chétifs tesmoings de la valeur de ces gens de bien. But results prove that it was no play. Maugiron and young Schomberg were slain on the field. Ribérac died the next day, Quélus a month later. Livarot lay ill for six weeks of a wound in his head, but at last recovered. Le bel Entraguet alone came off practically unscathed. The king would have gladly brought him to the scaffold, but Henri de Guise put out his powerful arm to protect his friend, who had only acted, he said, as an honourable man should. So Henri de Valois tamely sheathed his claws.

Balzac’s subsequent career suggests that gratitude was not a virtue he cultivated. At first he threw in his lot altogether with the Guises and joined the League. But when he found that he did not get as much out of it as he had hoped, he began to look again towards the court. His brother, François Balzac d’Entragues, was lieutenant-governor of Orléans, and with him he conspired to sell the town to the king. After some haggling the bargain was struck. François was made governor and Charles lieutenant in Henri’s name.

It was a barren bargain for the Valois. Orleans might be sold but the men within the walls refused to shift their allegiance. Charles Balzac, however, remained faithful to the king. By Henri IV. he was held in some esteem, received several honourable appointments, and was admitted to the Order of the Holy Ghost. In 1599 he was espoused to a daughter of the famous Marshal de Montluc, but died before his wedding day, and just too soon to see his niece, Henriette Balzac d’Entragues, raised to the honourable position of maîtresse en titre in succession to Gabrielle d’Estrees.

Henri’s grief for this slaughter of his favourites was boundless. Day and night he sat by Quelus’s bedside, attending to his wants with his own hands. The favourite had nineteen wounds and a pierced lung. There was little hope of his recovery. But the king refused to despair. He even tried to bribe the destinies. He offered Quelus himself a hundred thousand crowns, and the surgeon a hundred thousand francs if the patient should live. Chains were stretched across the road in front of the Hotel de Boisy, where the sick man lay, that he might not be vexed by passing traffic.

Now that Quelus was dead there was none dearer to the king than Paul d’Estuer de Caussade de Saint-Mégrin. A brilliant Gascon, he had won Henri’s favour by his handsome form, his intellectual cleverness and physical abilities, his exquisite taste. His two passions were love of women and hatred of the Guises. He used the one to further the ends of the other. He is said to have been loved by the proud Princess of Condé, and, it is hardly necessary to add, by Marguerite of Navarre. He laid siege to the hearts of the Duchess of Guise *) and of the Duke of Mayenne’s mistress, striking thus at the two greatest men of the great family whom the king himself so feared. One day he spitted his glove on his sword’s point, and boasted that he thus would serve the princes of the house of Lorraine. Doubtless all this was fine entertainment for the loungers of the Louvre, but it was a dangerous game. Henri of Guise, in his large way, scorned to notice the young man’s Gasconnades. His brother Mayenne, however, was less magnanimous. It must be remembered that the scandal touched Guise’s wife, but Mayenne’s mistress.

It was all in vain. On the last day of May the end came. If Henri was sorrowful at losing Quelus, Quelus regretted leaving Henri. ‘My king, my king’ were his last words. He spoke neither of his God nor of his mother, says Lestoile, shocked. Tenderly Henri kissed his dead friend’s lips, and took from his ears the earrings he had given him. With anxious care he saw that he who in life had so loved to be fairly apparelled, should in death be comely to look upon.

It was Henri’s will that Quelus should lie in state, as though he had been a prince or some great patriot. Then he was buried with Maugiron in the church of Saint Paul. The whole court watched the funeral. Only Henri was absent. It was not customary for kings to attend these melancholy ceremonies. On that very day he laid the foundation-stone of the great bridge destined to stretch from the Quai des Augustins to the Quai de Louvre. But in the evening he shut himself up with his grief and refused to see any man.

The obsequies of Quelus and Maugiron were celebrated in royal fashion. The court mourned as though kings were dead. Special panegyrics were prepared. Poets like Ronsard and Philippe Desportes were bidden write elegies. Despite popular murmurings, statues of marble were set up in the church of Saint Paul. Soon a third was added.

*) Henri of Guise had a son who was camus (flat-nosed). There is a legend

that Saint-Mégrin had the same deformity, and on that ground he has been

reputed the boy’s father. But, in his portrait, the minion’s nose is quite shapely; and, seeing that Henri III. chose his favourites largely for their good looks, there seems little reason for accepting the story.

Late on a July evening of that fatal year, 1578, as Saint- Mégrin was strolling down the Rue du Louvre in the direction of the Rue Saint Honoré, twenty or thirty men set on him with swords and pistols. Their work was soon over. They left their victim for dead on the street; and when one learns that he bore thirty-four or thirty-five mortal wounds, one does not wonder that the assassins were satisfied. Nevertheless, the tough Gascon did not expire till the day following. He was carried to the Hôtel de Boisy, where Quélus had died but two months before. Like his colleague, he was buried at Saint Paul’s in stately manner; an eulogistic funeral oration was delivered; and, as already mentioned, a statue was set up with those of Quélus and Maugiron. It was these statues to which the people of Paris, who detested the mignons, particularly objected. In the days of the barricades they showed their resentment by mutilating them.

This time the king made no attempt to punish his friend’s murderers, one of whom was reported to have borne a marked resemblance to the Duke of Mayenne. It is probable that his spirit was broken.

The old order was changing. Duel and ambuscade had almost exterminated the old brood of perfumed dandies. In the following year, almost the last of those who had quarrelled with Bussy d’Amboise left the court in disgrace. Two versions are given of Saint-Luc’s fall from favour. According to Lestoile, his wife, Jeanne de Brissac, who was ‘ugly, hunchbacked, and worse,’ waxed indiscreet about the king and the Duchess of Aumâle.

According to D’Aubigne, Saint-Luc, on the advice of his wife and Joyeuse, made an attempt to wean Henri from his evil courses. In the middle of the night, by means of a brass tube presumably a megaphone introduced into the king’s bedchamber, he threatened his master in awful tones with the judgment of God.

Poor Henri, whose nerves probably were not very sound, was nearly frightened out of his wits. Whether the supernatural voice would have had any effect on his subsequent conduct cannot, unfortunately, be determined; for the false Joyeuse betrayed the whole trick. The unattractive Jeanne was thrown into prison, and François d’Epinay, lord of Saint-Luc, having bought the governorship of Saintonge and Brouage, shut himself up in the latter and consoled himself with study and the writing of verse. He fought on the losing side at Coutras, where Joyeuse was slain, and after doing good service to Henri iv., met his death at the siege of Amiens in 1597. He was made of better stuff than most of the mignons of his time.

The name of Joyeuse brings us to the second epoch of Henri de Valois’s mignons. For two distinct periods are marked in this reign of favourites, of which the bloody year is the dividing line. In the earlier time Henri was surrounded by a crowd of young men, some of whom were brave enough, some of whom were mere fops and swaggerers, but none of whom played any great part in public history, or had any hand in their country’s destiny. In 1578 swift tragedy cleared the stage for men of a different stamp. Though chosen for much the same reasons as their predecessors, Anne de Joyeuse and Jean Louis de Nogaret were of far more ambitious nature. Unlike Quélus or Du Guast, they would not brook a host of participators in their privileges. There were only two mignons now, and each thought there was one too many; and after Joyeuse’s death there was only one.

For half a year after Saint-Megrin’s assassination the country was insuspense. There were still youngmen in plenty about the king, but there was none who was in such an indubitable position of favour as Quélus, Maugiron, or Saint-Mégrin had been. There was precedent for the certainty that Henri would not be long without a boon companion. The question was: on whom would his favour be bestowed. Early in 1579 the question was answered. To a chapter of the Order of the Holy Ghost came the king accompanied by François d’O, Saint-Luc, Joyeuse, and Nogaret, all dressed in clothes to match his own. The significance of this honour was obvious.

François d’O was, of course, well known. For some time past he had enjoyed royal favour. As superintendent of finances he pandered to the king’s extravagance, while he filled his own pockets. He was not of the mignons, being already middle-aged, but was assiduous in introducing likely young men to the king’s notice.

Likely young men enough were his three companions at the chapter of the Holy Ghost, and it was obvious that they were to be the favourites of the future. Saint-Luc’s prosperity was short-lived, as has already been mentioned; and by the end of the year there were only two competitors.

Neither Joyeuse nor Nogaret were newcomers at the court, and both had already enjoyed some measure of favour. Joyeuse, or Monsieur d’Arques as he then was, had been of Quélus’s set, and one of the persecutors of the gallant Bussy. Nogaret, some years older, was a man of a different, a larger, nature, and had already shown his ability in matters more serious than the bickerings of pampered courtiers.

Born in 1554, the son of Jean de Nogaret, lord of La Valette, a gallant officer, Jean Louis was, together with his elder brother Bernard, afterwards Marquess of La Valette, sent, at the age of thirteen, to be educated at the college of Navarre in Paris. The two boys were placed under the protection of Villeroi, the secretary of state, a friend of their father, who hoped that this powerful man would be useful to his sons’ welfare. As it turned out, Villeroi proved, in later years, one of the Nogarets’ bitterest enemies.

It was not long, however, before La Valette, finding his sons to be more ardent for arms than for the arts, wisely consented to let them have their way. They followed, him, therefore, through the latter stages of the Third Religious War; and on one occasion the future favourite saved his father’s life at no small risk to his own.

When war broke out again, the two brothers went to play their parts at the siege of La Rochelle; but without their father this time, for the jealous machinations of the powerful marshals, Biron and Bellegarde, debarred him from any chance of adding to the reputation which he had won at Jarnac and Moncontour.

Forbidden to have any intercourse with the two marshals, the young men were recommended to the Duke of Guise, the third of the generals who were serving under the Duke of Anjou at the siege. From the duke they got fair words, and were for a time devoted to him; but when, after their father’s death, which shortly occurred, they found that he intended to do nothing for them, their devotion cooled. Memory of this early disappointment was probably mingled with loyalty to his master in that hatred which the Duke of Epernon was afterwards to evince towards the Guises and their doings.

Soon afterwards, Jean Louis became the friend of another man who was subsequently to be his enemy. The younger Nogaret, known in those days as Monsieur de Caumont, made his first appearance at court towards the end of 1574, soon after Henri III.’s return from Poland. At the court was the young King of Navarre, still a professed Catholic, but suspected of undue sympathy with the Huguenots, and therefore kept a virtual prisoner by his masterful mother-in-law.

It is true that his captivity was an easy one. The life at the court was just such as one side of his nature loved. It was a time of peace, and luxury and love-making were the order of the day; which things none liked better than Henri of Navarre. None the less, even the shadow of detention irked the proud Béarnais. He determined to escape, and told his determination to Caumont, with whom he had struck up a close friendship, finding in him a congenial mixture of luxuriousness and daring.

So Caumont’s first visit to the court in which he was soon to be so conspicuous a figure ended in a sudden flight. For he was one of the five or six who, on the pretence of going a-hunting, rode one morning further than deer would have led them. He accompanied Henri of Navarre as far as Alençon, where an incident occurred which was apparently the cause of his deserting his friend.

The king’s physician invited his master to stand sponsor to his child. Henri complied, although the ceremony was to be according to the Huguenot form. He held the Huguenot faith in at least as much reverence as the Catholic. Not so Caumont, who, with what seems incredibly bad taste, turned the service into a farce by his buffooneries. Henri was naturally annoyed, and administered a snub to his too presumptuous friend. Caumont, who had expected the easy king to applaud his jest, saw in his seriousness an indication that he was soon to change his Church. The conclusion, though correct enough, was not a necessary one to draw from the facts. Howbeit, the young man shortly made an excuse to leave Navarre, and was soon for the second time on his way to court.

His reception, both from Henri in. and from the queenmother, was very favourable, for he brought letters calculated to make him acceptable, the which he had obtained from the governors of Guienne and Angoulême. His ability commended him to Catherine, though the king probably set more store by the lighter side of his character. That Caumont could be frivolous, the incident at Alençon is proof. His extravagance appeared when he decided to join the army which the king’s brother was to lead against the Huguenots. Henri was so pleased with Caumont’s patriotism that he presented him with twelve thousand crowns for his equipment; of which sum he made such magnificent use as entirely to eclipse the rest of the army.

In spite of these virtues, it was some time before Caumont took his place as a recognised favourite, and even after Henri had given so signal a demonstration of his affection at the chapter of the Holy Ghost, he was undoubtedly for a time second to Joyeuse.

Seven years younger than his rival, and brilliantly handsome, Anne de Joyeuse, Sieur d’Arques, was more of the authentic minion type. The eldest son of Guillaume II., Viscount of Joyeuse, of an ancient house, he was brought up in a fine tradition of chivalry; while his mother, Marie de Batarnay, inspired him with her own devotion to the Catholic Church.

As a young man at court, he was a minor member of Quélus’s party, and before 1579 ms most redoubtable achievement was a share in an ambuscade against Bussy d’Amboise. He had, however, in a high degree that charm and gallantry which was the passport to Henri’s favour, and his succession to the office of chief minion must have been far more expected than Caumont’s.

He was only eighteen at the time, and altogether lacked his rival’s experience of affairs. Nor did he ever show Caumont’s ability. The characters of the two men were strongly contrasted. Nogaret was made for success, Joyeuse for failure. The one, a man of no great birth, had the will and the power to push himself forward; the other, an aristocrat to the finger-tips, was at the mercy of circumstance.

Circumstance at first was kind enough to Anne de Joyeuse. He was honoured by the king, overwhelmed with favour. Moreover, he was allowed to win glory cheaply. In 1580 Henri decided to drive the Huguenots from La Fère, which was too near Paris for his liking. The siege became known as the ‘Velvet Siege’ because it entailed so little danger to the besiegers. Joyeuse, nevertheless, had his jaw broken and seven teeth knocked out by a ball from an arquebus. The wound did not dis figure him, but, for the moment, he was a hero.

It was not long before he received a distinction greater than had as yet been shown to any other of the mignons. He was offered the hand of Marguerite of Lorraine, sister of Henri’s handsome queen. Notwithstanding his previous engagement to Marguerite de Chabot, the Count of Charny’s daughter, he gladly availed himself of the chance of becoming so nearly allied with the royal house. Mademoiselle de Chabot must find another husband.

The betrothal took place in the queen’s chamber at the Louvre, 18 September 1581. Six days later the wedding was celebrated at Saint-Germain l’Auxerrois with the utmost magnificence. Let Lestoile describe the scene. ‘The king led the bride to the church, followed by the queen, the princesses, and the ladies of the court, so richly and grandly clad that nothing so sumptuous can be remembered in France.

The dresses of the king and of the bridegroom were the same, covered with embroidery and with pearls and jewels, which could not be counted, for such a costume cost ten thousand crowns. And at each of the seventeen entertainments which day after day, at the king’s command, were made after the wedding by the bride’s relatives, and other great princes and lords, all the lords and ladies appeared in new costumes, which were mostly of cloth of gold and silver, embellished with lace, guipure and embroideries of gold and silver, and with gems and pearls in great number and of great price.

The expenditure was so enormous, including masquerades, combats on foot and on horseback, jousts, tourneys, music, dances, and the horses and presents and liveries, that it was rumoured that it could not have cost the king less than twelve hundred thousand crowns. In fact, the cloth of gold and silver everywhere, even to the masques and chariots and other devices and the dresses of pages and lackeys, the velvet and embroidery of gold and silver were spared no more than if they had been given for the love of God.

And everyone was astonished at so much luxury and such enormous and unnecessary expenditure as the king made and his courtiers by his special command, especially as the times were not the best in the world, being troublous and hard for the people in the country, devoured and gnawed to the bone by the soldiery, and in the towns by new offices, duties and taxes.’

The poor people might groan, and moralists like Lestoile disapprove, but the marriage of the king’s favourite must be fittingly celebrated. On 15 October, at the Hotel de Bourbon, an entertainment was given which is not without significance in the history of the opera. This was the Ballet de Circé, invented by Balthazar de Beaujoyeue, one of Catherine de Medici’s Italians, who enlisted the musical and poetic and artistic and dramatic talent of the court to make his production a success.

Before his marriage, and in order to make him a more suitable match for the queen’s sister, Joyeuse had been created Duke of Joyeuse and a peer of France, with precedence of all other peers except the princes of the bloodroyal. The rich territory of Limoux was given him; an estate which seemed destined to belong to a royal favourite, for the Duchess of Étampes and Diane de Poitiers had both held it. In quick succession he was made Admiral of France, a knight of the Order of the Holy Ghost, and Governor of Normandy. His name was in every one’s mouth, and those who did not love Henri and his circle spoke it with scant courtesy or delicacy.

Meanwhile, though in those days the king undoubtedly preferred Joyeuse, Caumont was not by any means forgotten. Indeed Henri showed considerable anxiety to keep the balance between the two fairly weighted. But while Joyeuse was essentially the kind of man whom he loved to have about him, he found it necessary to school the elder favourite. Caumont was clever and showy, but he had not naturally the easy elegance of the true minion.

There is a story, for instance, of his coming into the king’s presence with his dress in disarray, his laces untied, his buttons divorced from their holes. Now Henri was a dandy, and expected his favourites to be well dressed. Caumont’s appearance shocked and annoyed him. He told him sharply never again to enter his presence in such a condition.

So perturbed was the young man that he prepared to quit the court, and would have done so had not Henri sent for him and gently admonished him for his hot-headedness, upon which he decided to remain, and for the future to look to his buttons. In order to acquire the cultivation necessary for his position, he associated himself much with Philippe Desportes, who took up his education at the point where it had left his books for the sword.

From the moment of their accession to favour, both Caumont and Joyeuse were frequently called to the king’s most intimate and weighty councils. As early as 1579, Caumont was entrusted with his first important commission. This was an embassy to Emanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy, the object whereof was to dissuade that prince from his intention of attacking the Genevese. The success with which he performed his part confirmed him in his position.

Just a year after Joyeuse’s promotion to the peerage, a similar honour was done to Caumont. He was presented with the manor of Épernon, which was elevated into a duchy, and created a peer of France with precedence, like Joyeuse, of all the peers except those of the blood, but with the further exception of Joyeuse himself. Naturally the other peers murmured at these sudden elevations.

Henri was evidently determined that neither of his favourites should ever complain that he was unduly partial to the other. He had advanced both to ranks in the peerage as nearly as possible identical. He had married Joyeuse to one of his sisters-in-law. He proposed to marry Épernon to another.

The chosen bride, Christine of Lorraine, the last of the queen’s sisters, was at the time too young for wedlock; but the dowry of three hundred thousand crowns was given to the favourite in advance. But the marriage never took place. Why Épernon refused such an alliance it is difficult to say. Possibly, as was rumoured at the time, he wished by his modesty to throw into relief the ambition of Joyeuse. Possibly his reasons were more political. Marriage with Christine, while it joined him to the royal house, would connect him no less with the Guises. He may have desired, in view of the coming struggle, to keep himself free from all obligation to the chiefs of the League. At any rate, that he felt himself strong enough to refuse a bride offered him by the king and that bride of so higha rank is very significant. One feels that Joyeuse could never have done the like. Some years later, Épernon married Marguerite de Foix, Countess of Candale, the heiress of an illustrious house.

His refusal to mate with Christine of Lorraine resulted in no diminishment of prosperity. His offices and estates were ever increasing. He had the government of Metz and the Metzin country, of Dauphiné, Boulogne, Calais, La Fére, Loches, and Lyons. The scantily-filled treasury was the emptier because of him. He did not forget the ties of kinship. His brother, La Valette, was only less well provided for than himself.

The death of the king’s brother, Alençon, in 1584, made Henri of Navarre, now the acknowledged head of the Huguenots, next heir to the throne of France. That a heretic should ever mount the throne was unthinkable to the extreme Catholics, the Guises, and their followers of the Holy League. Henri of Navarre was their archenemy; and the feeble Henri of France, vacillating between the two parties, without the determination to espouse the cause of one or other, or the power to take an independent course, they regarded with little more of friendship. Their oath was to rid the country of the accursed heretic, and if the keeping of it involved hostility to the anointed king, it was not their fault. Their attitude became more and more threatening; their intercourse with Spain more and more significant.

At a council which Henri of France held to consider the situation, Epernon expressed himself vigorously in favour of making immediate war on the League. Such powerful men as François d’O, the Chancellor Chiverny and the Duke of Retz were on his side, and the king approved his words. But there were also powerful men in favour of arbitration and agreement with the Guises; and Catherine, whose sympathies were with the house of Lorraine, gave, as always, the casting vote. So the fruitless negotiations began which ended, after all, in the war of the three Henries.

Among those who had voted against Épernon was Anne de Joyeuse. A sincerely devout Catholic, he would countenance no alliance with the Huguenots such as was implied in a war against the League. Ambitious, he dreamed of one day supplanting Guise as the head of the Catholic party. Apparently on friendly terms with the house into which he had married, he was secretly consumed with jealousy of their influence. He dreamed of power which he was not the man to realise.

A position which he coveted, as one that would increase his prestige, was the governorship of the Languedoc. He asked the king for it. Henri, who hated to refuse a favourite, hesitated. The office was in the hands of the constable Montmorency, a faithful servant whom he had no desire to depose. Joyeuse, accustomed to have what he wanted, was depressed. He decided to go to Rome, nominally on a journey of business or devotion, actually to interest Gregory XIII. on his behalf.

According to Thou, what he said to the pope was one long indictment of Montmorency, accusing the constable of favouring the Huguenots, painting Languedoc as a hotbed ofheresy, ‘so that it seemed as though all Germany

and Geneva itself were transplanted there’ The king, Joyeuse affirmed, would not, out of respect for the holy see, take action against the constable without first consulting his Holiness; to which end he had sent the duke, whom he was pleased to call his brother, as his ambassador.

Gregory, however, had reasons to support Montmorency. The constable was, it is true, on ill terms with the Guises and on good terms with Navarre, Condé, and the Huguenots. But he had protected the papal lands in France from the spoliation of the Protestants, and was therefore himself deserving of protection. Moreover, Gregory knew perfectly well what were Joyeuse’s motives. So he administered a snub to the minion, who went away discomfited and embittered. His disappointment was so great as to cause him a serious illness.

Leaving Rome, he went to Venice, seeking consolation in the magnificent welcome accorded by the city to one whom the French king held so dear. At Florence, at Ferrara, at Mantua, in Savoy, he received similar ovations. But what pleasures he got from the shows of honour were soon changed to bitterness. It was whispered in his ear that his supremacy with Henri had passed in his absence, that the balance of favour had shifted to Épernon’s side. He returned to Paris a soured and sombre man. Of a brooding nature, inclined to melancholy, a dreamer rather than a doer, one impotent to mould events, he was crushed by misfortune. In the sun of success, all his charm and grace shone out. When the clouds came up, he grew sullen and restless and bitter, not such a man as the king desired to have at his side.

Meanwhile, Epernon was at the head of affairs. Joyeuse was a member of the League, a zealous Catholic. Epernon advised Henri to join with Navarre. He himself went on a secret embassy to the Huguenot monarch (under pretext of a visit to his mother), travelling, nevertheless, with a magnificent train and finding a royal reception at every town through which he passed.

He had three conferences with Henri of Navarre, the first at Saverdun, the second at Pamiers, where the monarch, feeling himself unable to emulate the splendour of the ambassador, met him humbly on foot. The third meeting was at Nerac, and though, because of Navarre’s refusal to change his religion, no formal alliance could be entered into, there was a very distinct understanding that the two kings were to aid one another against the machinations of the League. One result of Épernon’s embassy was a meeting with Navarre’s sister, Catherine, Duchess of Bar, which resulted in a firm friendship, and seemed likely at one time to lead to a marriage.

The duke rejoined the French king at Lyons, and there, as he entered the city, an accident occurred which might easily have had a fatal ending. The sword of one of his gentlemen got entangled in the bridle of the duke’s horse. The horse took fright and bolted. Épernon lost control and was borne over the edge of what his biographer calls a ‘dreadful precipice.’ Every one thought he was dashed to pieces, and the news quickly reached the king, whose grief was boundless. But his tears soon had to be dried, for the duke was found alive and suffering no more than a dislocated shoulder, though the horse, which had fallen square on its four feet, had been killed by the shock. This incident set the fantastic and futile wits to work. The triumph of their ingenuity was a figure of the duke hanging over a prodigious precipice, while Fortune ran to rescue him. Underneath was the punning motto: Eper non lasciarti mai (‘And to never leave you’). So pleased was Épernon with this device that he had it engraven on a cornelian which he set in a ring, and wore as a talisman.

The duke’s embassy to the King of Navarre, which it was impossible to keep a secret, was very naturally used by the Guises as an argument that Henri in. was a traitor to the Catholic faith. Épernon’s personal unpopularity with the powerful house was increased by the extravagant favour which the king best owed on him. For the minion stood higher than ever. The Duke of Guise, thinking it better to have him for a friend than an enemy, had tried to buy his alliance with the offer of his daughter, the Princess of Conty.

But Épernon was ever haughty where his marriage was concerned, and this suggestion, like those connected with Navarre’s sister and France’s sister-in-law, came to nothing. Henceforth there was no friendship between the two dukes. Nor were matters mended when Henri III. tried to oust Guise from his office of Grand Master of the Household, in order that he might give it to his favourite. Though foiled in this, the king was determined that Épernon should have a post which would make him officially equal to Joyeuse the Admiral. He created a new office, or rather fused two old ones; and he who was already so rich in honours became Colonel-General of France with absolute power to appoint officers to any vacancies in the army.

Guise’s patience was at an end. He published a manifesto against the favourite, and took the field. His first attack was directed against Metz, the governorship of which was one of Épernon’s most important posts. Repulsed here, the League was none the les successful but this is no place to trace the history of the campaign, relieved by no heroic incidents, which ended in the Treaty of Nemours, *) whereby the King of France became nominal head of the League, and Catholics joined forces against the heretic King of Navarre.

*) The Treaty of Nemours was concluded on 7 July 1585 between the Queen Mother, Catherine de’ Medici, acting for the King, French King Henry III and the French Catholic League, represented by Duke Henri I de Lorraine, duc de Guise. The king recognised the League, revoked all previous edicts of tolerance in matters of faith and undertook to expel all Huguenots from the country. The Protestant side then took up arms and the eighth Huguenot War broke out. Before, on 10 June 1584, the Duke of Anjou, François d’Alençon, died. Henri III had no children and it was doubtful whether he would ever have any. The legitimate successor became the leader of the Protestant party in Navarre. Under no circumstances did the Catholics want a Protestant sovereign who might impose his religion on the whole kingdom. They sought the adoption of a new condition for access to the throne: being a Catholic. In the spring of 1585, the reinvigorated Holy League took control of many towns. In an attempt to control the League, Henry III declared himself its leader on 7 July 1585. As a gesture to the League, he published the Edict of Nemours, which obliged him to break with the King of Navarre.

It was in the war which followed this treaty that Joyeuse closed the life which had become burdensome to him. While the colonel-general and his brother were campaigning successfully in Provence, Duke Anne, who since his return from Italy had been living in idleness, brooding over his master’s declining favour, was put in charge of the army in that Languedoc which he had coveted with such unhappy results.

His conduct in this charge can only be described as ‘swagger’ Bidding farewell to the king, he promised to sack all the towns of the Huguenots and to perform prodigies. His equipment and that of the young men who followed him were superb in their luxury. En route he tarried to take baths at Bourbon-l’Archambaut for some ailment in his thigh.

After taking one or two places of small importance, he laid siege to Marvéjols, one of the most prosperous towns of Languedoc. The place capitulated, but was none the less sacked and burned, and the inhabitants were put to the sword. This indifference to the amenities of warfare was a presage of the cruelty which was a year later to characterise the conduct of a man who had, in days of prosperity, been of the gentlest.

For all his boasting, Joyeuse was content with a few small successes. He had only set out in the late summer. By October he was back in Paris, causing the tale of his deeds to be written and published in terms of the most extravagant eulogy. The fulsome praise bestowed on him and his generalship reads like sarcasm in the light of future events.

In the following year 1587 he was instructed to go against the King of Navarre, and to keep him from crossing the Loire. But he held lightly by his instructions. Leading his army into Poitou, he conducted a campaign which must have made his name stink in the nostrils of the humane.

His sincere hatred of heresy had developed into avengeful cruelty worthy of an Alva. What, if Marvéjols had been an isolated place, might have been thought an instance of the regrettable but excusable apathy of an unhappy man, showed itself plainly as the deliberate and determined cruelty of the general. Town after town suffered the fate of Marvéjols and worse. Saint-Maixent, Croix-Chapeau, Tonnay-Charente, Maillezais, in turn capitulated. To each was meted the same treatment. The soldiers were allowed to ravage and rape at their pleasure. Officials were hanged. The throats of prisoners were cut. Joyeuse made the bitter boast that the preachers of Paris should have some cause to speak his name.

Conduct of this sort naturally disorganised his troops. Discipline became lax. Uncurbed licence and luxury resulted in disease among the soldiers, and Joyeuse found it necessary to return to court, leaving in Poitou a Satanic memory.

The king gave his old favourite a cold welcome. He was busy dancing at the wedding of Épernon, who had at last married Marguerite de Foix, and had nothing to spare for Épernon’s rival; nothing except the ungenerous and unjust suggestion that Joyeuse’s return was an act of cowardice. The poor duke was desperate.

An event which increased his unhappiness was the death of Catherine de Nogaret, Épernon’s sister, and wife of his own brother, the Count of Le Bouchage. This lady, so nearly allied to both the dukes, had, by her gentle influence, often been able to prevent their hostility from breaking into open warfare. But now that she was dead there was no reason why Épernon, whose power was ever increasing, should not compass or hasten the ruin of his weakening rival. As for Le Bouchage, so affected was he by the loss of his wife, that he entered a convent of Capuchins as Brother Ange de Joyeuse: another grief for his brother, who loved him.

Longing for the opiate of action, Joyeuse obtained the king’s permission once more to take the field and to force a pitched battle on the King of Navarre. He was determined to prove how ill-founded was Henri’s charge of cowardice.

Joyeuse never lacked friends not even in adversity and the flower of the Catholic nobility joined his standard. On 20 October 1587 he met the Huguenots at Coutras. His own army was the larger, but as a general he was no match for Henri of Navarre, who, moreover, had Turenne and La Tremoille, Condé and Soissons, to support him.

The Catholic general led his men in one gallant charge against the enemy. They dashed through the advance guard, scattering the heretics. But before them stood the main body, compact, motionless, the arquebusiers waiting the word of command to pour death into the ranks of oncoming horsemen. In the midst stood Henri, crying to Condé and Soissons: ‘I will only say one thing, that you are of the house of Bourbon, and, by God, I will show you I am your head.’ In that spirit did Henri of Navarre win battles.

On came the sea of horses and dashed and broke against the rocks of Henri’s Huguenots. Saint-Luc, the old, discredited minion, rode by his companion in misfortune. ‘What is there left to do?’ he called out. ‘To die’ was Joyeuse’s answer. But Saint-Luc did not die. He became Condé’s prisoner, and lived to do good service for the man against whom he had ridden so desperately.

‘There are a hundred thousand crowns to gain’ Joyeuse is said to have cried, when surrounded and dragged down by his foes. But if, as has been very plausibly suggested, he was seeking death, these last words must be the invention of some imaginative historian. Die he did, at any rate, with a pistol-shot through his head. His brother, Saint-Sauveur, was also slain on Coutras field. The victory of the Huguenots the first they had gained was complete.

The grief which Henri showed for the death of his old favourite was greater than he can possibly have felt. For a time the body lay at Libourne, but in the following spring it was brought to Paris. Funeral ceremonies were arranged which recalled the extravagant magnificence of the duke’s wedding. An effigy of the dead man was carried through the streets, as though he had been of royal blood, or, at least, a constable. To no others was such honour due.

These proceedings were extremely unpopular. The Treasury was, as usual, empty, and people murmured that money and honour should be lavished on the corpse of one who had had so much of both beyond his deserts when alive, and had, moreover, led the arms of France to defeat. Even the funeral oration preached by the Bishop of Senlis – a keen Leaguer – was packed with satire.

Thus was the end of Anne de Joyeuse, a man whom ambition destroyed; one not without nobility, for he came to hate the shameful manner of his rise to power, but too small to achieve his ambitions greatly, and too weak to get out of the rut where his youthful graces had first led him.

Épernon was now the last as well as the greatest of the mignons. While Joyeuse had been in Languedoc, he had been in Provence, where his arms met with no small success. He took several towns from the Huguenots, and secured both Provence and Dauphiné for the king. Then leaving his brother, La Valette, as his lieutenant, he returned to Paris, having heard that some of his many enemies were taking advantage of his absence to calumniate him with the king. The man whom he chiefly feared was Villeroy, who, though he had been his father’s friend, and at one time almost the duke’s guardian, was now his declared enemy. Jealous of one who, though so much his junior, was so much greater with the king, the minister did all he could at every turn to thwart Épernon, opposing him in council, even scheming to get him removed from court.

A sum of twenty thousand crowns, designed for the payment of the army under La Valette, was used by Villeroy for another purpose. Épernon charged him with it in the king’s presence. Villeroy gave him the lie, and it was only because the king was present that swords were not drawn. Henri, who hated unpleasantries, slunk out of the chamber. No sooner was he gone than Épernon turned on Villeroy and abused him without restraint, raising his hand (say some)to strike him. The elder minister fled to the king. But, as will appear, Épernon’s troubles were not over.

Henri, however, was as devoted to his minion as ever. He gave him the command of the vanguard of his own army. At his marriage he presented him with four hundred thousand crowns: a barren gift, however, for the Treasury could not furnish such a sum. During 1587 Épernon was busily employed in harassing the German and Swiss troops which had come into France to aid their co-religionists. So well did he do his work that before the end of the year they were glad enough to come to terms, and to depart to their own countries. The battle of Coutras was no evil day for him. He was not only at once invested with all Joyeuse’s numerous offices, from that of admiral downwards, but he also had those of his cousin Bellegarde, who fell on the same field.

Meanwhile the power and popularity of Henri of Guise was steadily increasing. It was to him and not to the king that people gave praise for the victories over the heretics. Handsome and generous, a fine soldier, swift in action, he fired the imagination. The degenerate, vicious Valois was held in contempt, his proud and avaricious minister in execration. It was to the head of the League that Catholic France looked for salvation. Paris would gladly have crowned him king.

The Guise hated Épernon, whom he regarded as one of the causes of the dissensions of France. In the name of the League, he petitioned for his removal from court, on the grounds of his sympathies with Henri of Navarre. The king rejected the petition, but he could not save his favourite from the attacks of the satirists, who lampooned him under the name of Gaveston. As for Épernon, he did not hesitate to advise the execution of his powerful enemy.

The favourite was not in Paris on the day of the Barricades, when the city rose against its sovereign, excited by the fancied danger of their beloved duke. Bu the joined Henri at Chartres, whither the king had ignominiously fled. During the riots, the furniture in his hotel was

destroyed by the mob.

He had just been in Normandy, taking possession of the government of that province, one of the best fruits of Joyeuse’s death. Everywhere he had been received with acclamation: for Normandy, with the exception of Havre, was staunchly royalist. Triumphant and arrogant, he now rode to Chartres with a train of five hundred gentlemen. Henri, in despair at the course of events, welcomed him with enthusiasm. Soon he was to have a less welcome visitor, one who was exacting in his demands.

For the Guise was in a position to dictate terms. He made good use of his position. One of his first requirements was the exile of Épernon. In this he had many with him, and none more zealous than the queen-mother, Catherine de Medici, who hated the favourite, and was on excellent terms with the League. An indictment was published not only of Épernon, but of his brother, La Valette, accusing them of favouring the Huguenots, of oppressing the people, of monopolising offices.

If Épernon was Gaveston, Henri III. had none of the redeeming staunchness of Edward II. He could not suffer affliction or run into danger for the friend who, whatever his faults, had served him well. Weakly he consented that Épernon should be banished, and deprived of the greater number of his offices.

So in the June month of 1588 a year pregnant with the last of the mignons took a tender farewell of his master, who, to prove that his favour was not abated, made him generalissimo of the forces in half a dozen provinces.

Épernon retired first to Loches, where he busied himself about his new charge. There he soon heard serious news. Now that they had contrived to separate him from the king, his enemies had been making more headway in their designs of bringing him into absolute discredit. Circumstances, not inclination, had made Henri banish his favourite. Now, however, his weak, vacillating heart was turned against him. He was soon convinced that Épernon was a traitor, and was ready to take any measures against him.

The duke still had friends at court who kept lim acquainted with how things went. Realising his danger, he decided to leave Loches for the strong city of Angouléme, where he would at least be able to defend himself. It is much to his credit that at this juncture he refused to listen to the overtures of Navarre, who tried to induce him to enter his service.

His reception by the townsmen of Angoulé’me was flattering; but he had not been two days behind its walls when dispatches came from the king, signed by the old enemy, Villeroy, to the chief officials of the city, ordering them to close their gates against him. The letters came too late to achieve their purpose, but their effect was none the less. The consul at once sent a message to court proposing that he should seize the duke and keep him a prisoner until instructions came from the king.

Villeroy, replying for Henri, or more, perhaps, for himself and Guise, willingly assented to this course, adding that Épernon was to be taken alive or dead. There is a story that the messenger received his answer from a man disguised as the king.

Meanwhile Épernon, in utter ignorance of what was forward, was living in the city as befitted his rank. Naturally he received many visits from the principal inhabitants. On Saint Lawrence’s day the consul paid him a morning call. The duke asked him to come back again to dinner. The consul consented gladly; he saw a chance of acting on his mandate. He made his dispositions. Armed men were lodged in houses near the castle, where Épernon dwelt. Others were to go about the streets, telling people that the Huguenots had made an attack.

At the appointed hour the consul, with two others, entered the castle. About the same time half a dozen other men, all spurred and cloaked, came in casually as though to pay their respects to the duke. The servants at the door, who knew the consul perfectly well and suspected nothing, told him to go to the wardrobe, where he would find his host. The consul proceeded to do so, followed closely by the others. At the door of the wardrobe, throwing back their cloaks and drawing swords and pistols, they dashed in with cries of ‘Kill!’ They were too soon, however. Their man was not there.

Épernon had, a moment before, retired to his closet. Hearing the tumult, for his servants were making a vigorous resistance, he bolted himself in. With him were his friends, the Abbot del Bene and Marivault, who aided him in piling furniture against the door, determined to hold out as long as possible.

Meanwhile the tocsin was ringing in the city. People were flocking to the castle, within which and without there was the wildest confusion. The gentlemen of the duke’s suit rallied, held the gate against the enemy outside, and at the same time attacked those inside. Hearing friendly voices among the tumult, Épernon and his two companions came out of the closet and took part in the fight. His peril was great. All the town was now in arms against him. His followers were few and the entrances to the castle many. Provisions were scant. Attempts to communicate with friends outside failed. The duchess, returning from Mass, was taken prisoner.

It was a siege within a siege. For while Épernon and his friends were being besieged within the castle, they in their turn were besieging the consul and his accomplices in a tower of it. So perilous at length became the plight of these last that the attackers found it necessary to parley, and terms would have been arranged, had it not been for some extremists, who were ready to sacrifice the consul rather than lose the duke. It was not until they were apprised of the near approach of Tagent, Épernon’s lieutenant, with his cavalry, which, at the outbreak of the trouble had been away at Xaintes, that the inhabitants consented to an arrangement, and the siege, which had lasted for two days, came to an end. Nor did Épernon take any revenge on the citizens, being dissuaded therefrom by his duchess, who had been their prisoner, and received rough usage at their hands.

After this episode Épernon was left, for the moment, in peace. In spite of all, he remained faithful to the king, resisting the renewed and repeated suasions of Henri of Navarre. Then an event occurred which altered the whole complexion of the affairs of France. The great Henri of Guise and his brother, the Cardinal of Lorraine, were murdered at Blois by the king’s orders. Catholic France took fire at the outrage, and the murderer was forced to look for protection to his Huguenot brother-in-law.

It was Épernon’s chance. Mayenne, now head of the League, was in arms; the Henries needed troops. The favourite sent more than two thousand men. The king was not ungrateful. He was glad enough to recall the man whose energy and ability had so often stood him in such stead. Épernon was placed with Biron at the head of the royal army. During the time that he was in command he acquitted himself well. But he was never again to be in his old high place. Eight months after he had spurned with his heel the dead body of the Guise, the last of the Valois himself fell a victim to a fanatic’s knife.

Épernon was among those who refused to recognise a Huguenot king, and retired again to Angouléme. His career was by no means finished. He had more than half a century of varied life still before him. While Henri IV. was on the throne he would be in comparative obscurity, but under Louis XIII. he would again stand in the forefront of events. But the pleasant and perilous days of the minion were over for ever.

Source: Kings’ favourites by Francis Lawrance Bickley. London: Methuen 1910.