REIGN OF LOUIS XVI, 1780 to 1789.

Journal des Modes de Paris

Content: Peasant dress is universal – “Fashion “à la Marlborough”- Caps – Bonnets – Mdlles. Fredin and Quentin – Ruches – Low bodices; “postiches” – Costume of Contat · Suzanne – Fashions “à la Figaro” – Literature and politics signified in dress; the Princess de Monaco’s pouf – Pouf “à la circonstance;” the “inoculation” pouf – The “innocence made manifest” caraco – The “harpy “costume – Coats, cravats, and waistcoats, Sailor jackets and” pierrots” – Déshabilles; “the lying fichu” – Etiquette in dress Seasonable costumes – The queen’s card·table – State of trade in Paris, circa 1787 – “Pinceauteuses,” or female colorers.

Peasant dress is universal.

IN 1780 the ideal of Fashion was the peasant costume. Duchesses playing at milkmaids in the park at Trianon adored everything rural, and did their best to resemble shepherdesses. They longed to play the parts of Mathurine and Nicolette, only their diamonds must still be allowed them. The Chevalier de Florian was beginning to acquire a reputation as a writer of pastoral romances, very much to the taste of the ladies of his time. His novel of “Estelle and Némorin” inculcated bucolic manners and graces.

But the humblest fashions may be splendidly travestied! Capbonnets were adopted by all the court ladies, but in combination with flowers, ribbons, and feathers, composing a charming springlike head-dress.

The smallest caprice of Marie Antoinette was still sedulously copied. One day she began singing the air of Marlbrouck,” and all French ladies immediately dressed “à la Marlborough”, and sung their queen’s favorite air from morning to night. Mme. Rose Bertin forwarded costumes “à la Marlborough” to England. In the previous century, Bachaumont had written as follows: “Ever since the song came out, Marlborough has become the hero of every fashion; everything nowadays is “à la Marlborough”, and all the ladies walk about the streets, or go to the play, wearing the grotesque hat in which they are pleased to bury their charms, so great is the empire of novelty.”

Fashion à la Marlborough by Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette partially revived the rage for fashions à la Marlborough. Four years later, Frenchwomen gave up the caps I have mentioned for straw bonnets from Italy, which were immediately preferred above all others, and which remained in fashion for above a century. One milliner would choose a shape with perpendicular crown, hidden under a mass of ribbon; another would adopt an enormous funnel-shaped brim, loaded with feathers or flowers.

Caps and Bonnets, Journal des Modes de Paris.

It has been calculated that in the course of two years, from 1784 to 1786, the shapes of hats were changed seventeen times. There were some called hat-caps, “chapeau-bonnets”, because their balloon shape resembled a cap.

There were small close shapes in silk, trimmed with feathers and flowers, worn on one side of the head; and soon afterwards there were very large bonnets “à l’amiral”. We read in the “Journal des Modes de Paris,” 1785: “There is a hat on view at Mdlle. Fredin’s, milliner, at the sign of the ‘Echarpe d’Or’ (Golden Scarf), Rue de la Ferronnerie, on which is represented a ship, with all her rigging complete, and her battery of guns. … At Mdlle. Quentin’s, in the Cité, there are ‘pouf’ hats composed of military trophies, the flags and drums arranged on the brim have a charming effect.” Some hats were so enormously large that they overshadowed the whole face like a parasol. And some aimed at satire; they were of black gauze, and called “à la Caisse d’Escompte”, because they were without crowns (sans fond). This referred to the wretched state of the public treasury; the Caisse d’Escompte having just suspended payment.

Gowns, whether of silk or of plain material, continued to be made open down the front, over an under-skirt of another color; but for a simple style of dress, both skirts might be alike. Gimp trimmings had been succeeded by ruches of muslin or lace, sewn to the edge of the dress, and arranged like flounces. Sleeves were always tight and short; fans and bracelets, pearl necklaces, and sometimes a watch, fastened at the side, were worn also, and immense earrings “a la Creole”, that had been first seen in Mirza, a ballet by Gardel. Gowns were worn rather long, scarcely revealing the satin shoes with buckles, and the smooth-drawn white stockings.

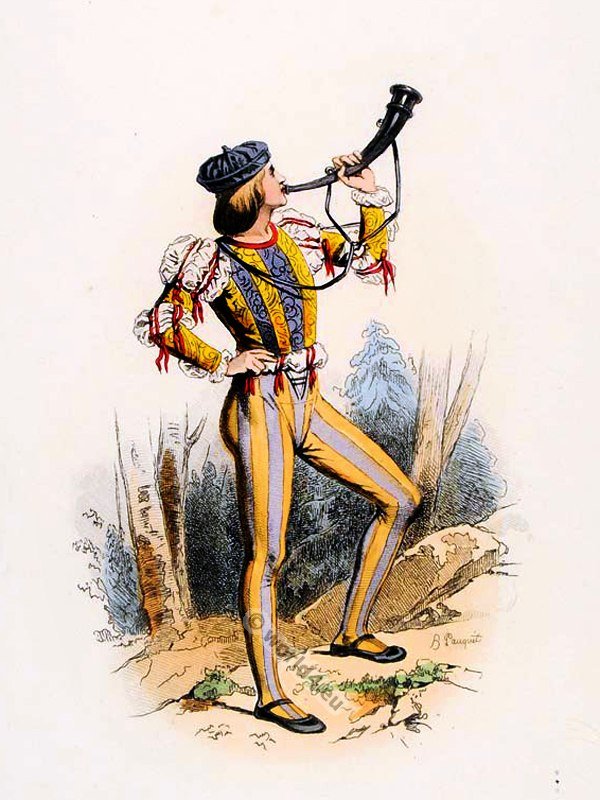

Fashions à la Figaro.

We may here recall the “calembourg” made by the Marquis de Brévre to Marie Antoinette: Madame, said he, P’uni vert’ (the universe) is at your feet.

By way of compensation for the length of the skirts, bodices were cut so low that the shoulders were visible. Paniers were out of date, but “postiches” had taken their place.

These postiches soon became so enormous, that even young and slender women looked like towers of silk, lace, ribbon, and flowers. Fashionable marquises wore satin pelisses, white, pink, or sky blue, trimmed with ermine or miniver, and a muff in winter. Occasionally, in a fit of simplicity, they contented themselves with a silk hat, and an elegant caraco, or a satin mantle trimmed with broad lace. Sometimes, also, they expressed their literary or political proclivities by their dress.

The Philadelphia cap was intended to commemorate the independence of the United States, about the time of Franklin’s visit to Paris. The immense success of Le Mariage de Figaro effected a change in the fashions, and the costume in which Mdlle. Louise Contat (1769-1846) had been applauded to the echo in the part of Suzanne in Beaumarchais’ Mariage de Figaro (Debut on October 5, 1784), became the order of the day. All that year, the ladies adopted “le deshabille a la Suzanne,” dressed their hair à la Cherubino, wore their gowns à la Comtesse, and their bonnets and caps à la Figaro.

After the performance of La Brouette du Vinaigrier, by Louis-Sébastien Mercier (1740-1814), caps à la brouette (wheelbarrow) came into fashion.

La Caravane, by André Ernest Modeste Grétry, brought out caps à la caravane. La Veuve du Malabar (1770), a five-act tragedy by Antoine-Marin Lemierre (1733-1793) was so popular, that extraordinary caps were devised “à la veuve de Malabar”.

Louis XVI. thought proper, on a certain occasion, to forbid the court in general to enter the royal carriages in order to follow the hunt. To ensure greater freedom, he desired the company of real sportsmen only. The nobles immediately protested, and the Princesse de Monaco expressed her disapproval of the new regulation through the medium of her “pouf” hat, on which was displayed the king’s coach in miniature, padlocked, and two gentlemen in gaiters following the hunt on foot.

On the left side of the “pouf de circonstance,” worn at the accession of Louis XVI., was a tall cypress, wreathed with purple pansies, a twist of crape at the foot represented its roots; on the right was a wheatsheaf lying on a cornucopia, from whence tumbled a profusion of figs, grapes, and melons, made of feathers.

The innocence made manifest caraco.

In honor of the discovery of inoculation for small-pox, Mdlle. Bertin invented the pouf à l’inoculation, viz. a rising sun, and an olive-tree in full fruit; round this was entwined a serpent bearing a club wreathed with flowers. The serpent and the club represented medicine, and the art by which the variolos monster had been vanquished; the rising sun was emblematic of the young king, in whom were centered all the hopes of the monarchists; and the olive-tree symbolized the peace and tranquillity resulting from the operation to which the royal princes had submitted.

The innocence made manifest caraco was invented in 1786, in honor of Marie Françoise and Victor Salmon, who had been tried on a charge of poisoning, and acquitted in the June of that year. The counsel for the defence was one Cauchois. The same caracos were also called à la Cauchois. They were of lilac pekin, with collars and facings (parements) of apple-green. They were fastened on one side of the front by four large mother-of-pearl buttons, and similar buttons were placed on the lapels.

The “harpy” costume.

In the catalogue of extraordinary costumes worn in 1783 and 1784 we must include the “harpy” costume, which owed its existence to the published account of the discovery in Chili of a two-horned monster, with bat’s wings, and human face and hair, which was said to devour daily one ox, or four pigs. A songwriter composed the following lines against the new fashion:

” À la harpie on va tout faire,

Rubans, lévites et bonnets;

Mesdames, votre goût s’eclaire:

Vous quittez les colifichets

Pour des habits de caractère.”

(” Everything is to be ‘à la harpie;’

Ribbons, frock-coats, and caps;

Ladies, your taste grows instructed,

You are abandoning gewgaws

For a costume in character.”)

An anonymous writer gallantly replied:

” La harpie est un mauvais choix;

Passons sur ce léger caprice ;

Mais dans les modes quelquefois

Le sexe se rend mieux justice,

En suivant de plus dignes lois.

Mesdames, j’ai vu sur vos têtes

Les attributs de nos guerriers ;

On peut bien porter des lauriers,

Quand on fait comme eux des conquêtes.”

(“The ‘harpy’ is ill chosen;

Let us pardon this caprice ;

But sometimes in the fashions

More justice is done to the fair .ex,

And worthier laws prevail.

Ladies, upon your heads I have seen

The attributes of our warriors,

And laurels may fittingly be worn

By those who are conquerors.’)

Coats, cravats, and waistcoats, Sailor jackets and pierrots.

The epigram did not modify the “instructed” taste of women, who continued to dress themselves à la harpie until the occurrence of some new whim. Our Frenchwomen, for instance, copied the English, who had introduced masculine fashions into their dress.

In all our public resorts, ladies were to be seen in coats, with braid and lapels, double capes, and metal buttons. The most elegant women were muffled up in cravats, shirt frills, and waist coats, and wore two watches with chains, breloques, and seals.

Some even wore men’s hats, and carried canes. The same ideas from across the Channel induced women to wear sailor jackets and pierrots. This latter appellation was given to a tight-fitting garment, cut low in the neck, and fastening in front, very open at the bottom; the sleeves were tight, with turned over cuffs (parements), and the long basques were trimmed with buttons.

A still more eccentric style of dress was that of gowns “à la Circassienne”, with a fichu or “canezou,” and an undress gown “en caraco”, so cut as to expose the pit of the stomach, notwithstanding the immense cambric kerchief that stood out preposterously in front, and was called by the malicious a “fichu menteur” (a deceitful or lying fichu). Gowns “à l’Anglaise” and “à la Circassienne” were for occasions of ceremony; coats, pierrots, and caracos for morning dress.

We may also mention among the whimsicalities of fashion, garments “à la Montgolfier” after the invention of balloons, sheath-dresses “à l’Agnes” and chemises “à la Jesus”.

The difference between full dress and half dress continued to be strictly observed; and before proceeding further we may point out that from the reign of Louis XIV. to the French Revolution the dress of men and women alike was entirely regulated by etiquette, by which we mean not the code of courtiers only, but the sanction of recognized custom.

Etiquette in dress Seasonable costumes.

Materials were classified according to the seasons. In winter, dress was restricted to velvet, satin, ratteen, and cloth. After the fêtes of Longchamp, which may be considered as the assizes of fashion, the lace called point d’Angleterre made its appearance. Mechlin lace was worn in summer. In the intermediary seasons of spring and autumn, light cloth, camlets, light velvets, and silks were habitually worn.

The queen’s card·table

Immediately after the Feast of All Saints, November 1st, all furs were taken from their cardboard receptacles, and at Easter tide most ladies put away their muffs. Full dress was obligatory for promenades in the Tuileries Gardens.

At court, when a lady had attained her eighth lustre, or, to speak more prosaically, when she reached the age of forty, she wore a coif of black lace underneath her cap, and tied it below her chin. The editor of the “Memoirs of Mme. de Lamballe” tells us that after “the queen’s card-table” (jeu de la reine) most of the ladies retired to change their gowns, because the front had been soiled by the gold they had received. Possibly they did not wish Louis XVI., who disapproved of the “queen’s card-table,” to perceive that their taste did not correspond with his.

State of trade in Paris, circa 1787.

At the close of the eighteenth century, Paris contained 38 master makers of needles and pins, 542 knitted cap and cuffmakers, 82 female bouquet-sellers and florists, 262 embroiderers, 1824 shoemakers, 1702 dressmakers, 128 fan-makers, 318 workers in gold and silver stuffs, &c., 250 glove-makers and perfumers, 73 diamond-cutters, 659 lingères, 143 dancing-masters, 2184 mercers, 700 barbers and male and female wig-makers, 24 feather-dressers and plume-mounters, 735 ribbon-sellers, and 1884 cuttersout of coats and gowns.

In 1776 the feather-dressers combined their business with that of fashionable dressmakers. Mercers sold lace, silks brocaded in gold and silver, gold braid, gold and silver net-work, and woolen materials of various kinds.

Turgot suppressed the guild of female bouquet-vendors, and ruled that women should pass “masters” in any profession suitable to their sex, not only as embroiderers and milliners, but also as hair-dressers. Increased grace and delicacy in feminine attire was the result of this innovation. Large numbers of skilled mechanics obtained a respectable livelihood by goldsmiths’ and jewellery work, by skin-dressing, or working in silk, wool, cloth, and cashmere.

Pinceauteuses, or female colorers.

Colored cottons were sold in great quantities; women were employed in their manufacture, to color the material. They were called ” pinceauteuses.” Very superior muslin was produced in France, and the art of dyeing made continual progress, owing to the efforts of the greatest chemists of the age.

From the princess to the working woman, the fair .ex neglected nothing that might increase their attractions. A moralist has justly observed: “I have heard of women wanting bread, but never of one who went without pins.”

We shall meet with some exceptions to this rule during the Revolution; but they only help to prove it, and were of brief duration.

Source: Costume design and illustration by Ethel Traphagen. New York, London: John Wiley & sons, inc. 1918.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.