1, 2, 3, 4, 5,

6, 7, 8, 9,

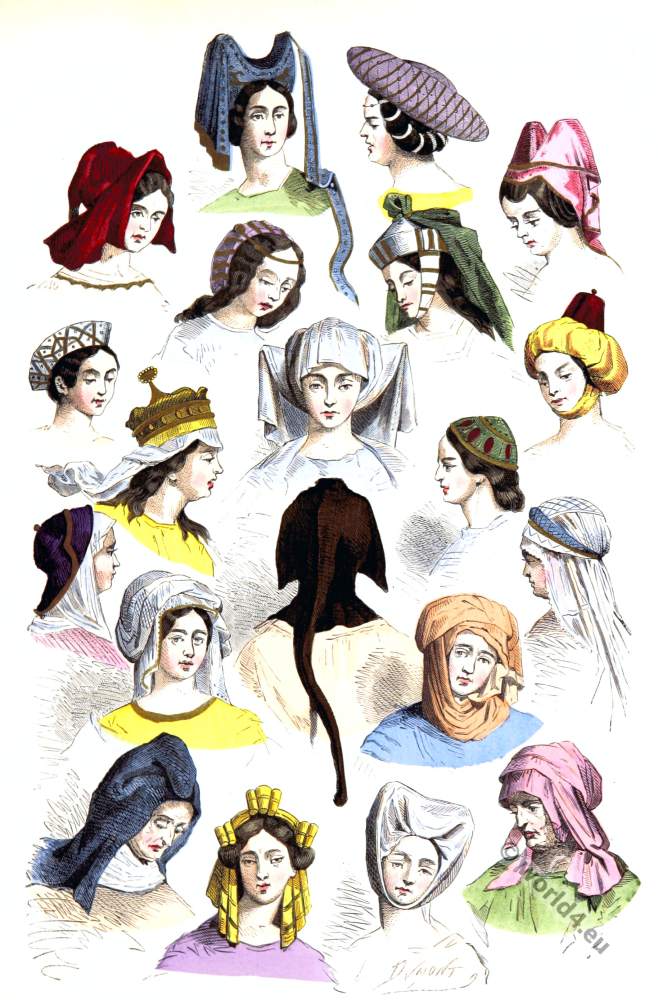

FRANCE. 18TH CENTURY. WOMEN’S DRESSES. FASHIONS FROM THE FIRST PERIOD OF THE GOVERNMENT OF LUDWIG XVI.

- No. 1. Young woman with a semi-circular cap, called à la latière, held together by a pink ribbon. The cape of Atlas is lined with fur, the throw called polonaise is of rose-coloured taffeta with blue stripes, the skirt is of the same fabric.

- No. 2. Young girl in the Caraco of Taffeta. The citizens of Nantes appeared in this costume during the passage of the Duke of Aiguillon in 1768. Military, as well as Foreign and War Ministers under Louis XV.

- No. 3. Woman in the polonaise of Taffeta. The gauze veil that is wrapped around the round cap was called thérèse.

- No. 4. Young woman with a headscarf, a fichu en marmot, a polonaise and a white coat.

- No. 5. Young woman whose headgear was called en baigneuse. She is wearing a cape of Atlas lined with fur. The skirt is decorated with a ruffle.

- No. 6. Dress à la Circassienne decorated à la Chartres.

- Number 7. Young girl in robe en levite with taffeta belt. Headgear à l’enfance and hats à la Jâquet.

- No. 8. Portrait of an unknown.

- No. 9. Robe anglaise. The striped gauze headdress was called Calèche.

During the turbulent reign of Louis XVI, French fashions underwent three major changes. The first period offers the excess of luxury, frivolity and excess, which was the final effect of the carnival that began with the dominos of the regency.

It is the time of the high hairstyles. The second phase was the revolution of simplicity. The women, who raved about battiste and gauze, appeared in shirt-like skirts, in négligés, which were called pierrots, in camisoles à la colinette and with the house dress à l’enfant. The charming costume of the chambermaid Susanne, which became popular through the performance of the Wedding of Figaro by Beaumarchais, is characteristic of this period. The third period is dominated by the intrusion of English fashions. The women wore overskirts, waistcoats and hats like the men and also carried walking sticks in their hands.

In the first of the three periods, the extravagance of women’s costumes exceeded anything that had been seen under Louis XV. Although the paniers, the basket-like crinoline skirts, were nearing their end, they were still expanding, so that their circumference rose to five metres. This encouraged the showing of the feet and shoes with high heels. At festivities, people wore shoes embroidered with gold and set with pearls and precious stones.

The exaggeration was particularly evident in the hairstyle. The construction of the hairstyle was driven to such a height that the head seemed to have two thirds of the body length. The coiffure called loge d’opera (1772) gave a lady’s face the length of sixty-two inches from the tip of the chin to the top of the hairstyle. This building was decorated with every possible artistic effort.

The hair was curled, braided, pomaded, coiffed and powdered white. On top of it was placed a cap decorated with ribbons and feathers; no fewer than two hundred such caps were counted, after which each headdress had a special name. The poufs were made of folded gauze. A hairdresser of this kind, named Léonard, once used fourteen cubits of gauze for such a pouf.

The pouf au sentiment was decorated with flowers, fruits, vegetables, stuffed birds, the namesakes of loved ones, shepherds, shepherdesses, hunters and mythological figures. The brothel was sometimes a rural poem, sometimes an English park with windmills, bosquets, streams and sheep, sometimes a decoration from an opera.

As the hairstyles gradually became so high that the ladies could no longer get through low doors and had to either kneel down in the coach or stretch their heads out the window when driving, the Coiffure à la Grand-Mère, invented by Beaulard, which had a spring mechanism on the inside, helped to make the artificial structure smaller by one or two feet if necessary. Our numbers 6, 8 and 9 show the degree to which this extravagance increased. Moreover, the robes were overloaded with decorations of all kinds: bows, bowls of cloth, tendrils, bouquets, pomegranates of gauze in garlands and trimmed with pearls and stones, along with the falbalas and the multitude of jewellery on the neck, chest, wrists and belt.

Around 1780 the reaction was already asserting itself. One wore a skirt à l’austrasienne, a jacket à la péruvienne and over it a belt. The breasts were almost completely exposed in this costume. Nos. 6 and 9 belong to the year 1778. They are reproduced in rare copper engravings, one of which is drawn by L. Berthet. In the case of ordinary toiletries one wore a short hooped skirt, over it the polonaise, a short overskirt with a wide cut-out body, which was gathered around it so that it formed three wings. When going out, one threw over a small textile coat or a cape of fur.

Coiffure no. 8 was named à la Montgolfier after the famous airship owner. The figure is modeled on an English engraving from 1783 or 1784.

(Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 7 are taken from the gallery “des modes et costumes français”. The first five figures are by Desrais, the sixth by Meunier. Cf. Quicherat, Histoire du costume en France, E. und J. de Goncourt, La Femme au XVIIIe siècle, Lacroix, le XVIIIe siècle et Mercier, Tableau de Paris.)

Source: History of the costume in chronological development by Auguste Racinet. Edited by Adolf Rosenberg. Berlin 1888.

Continuing

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.