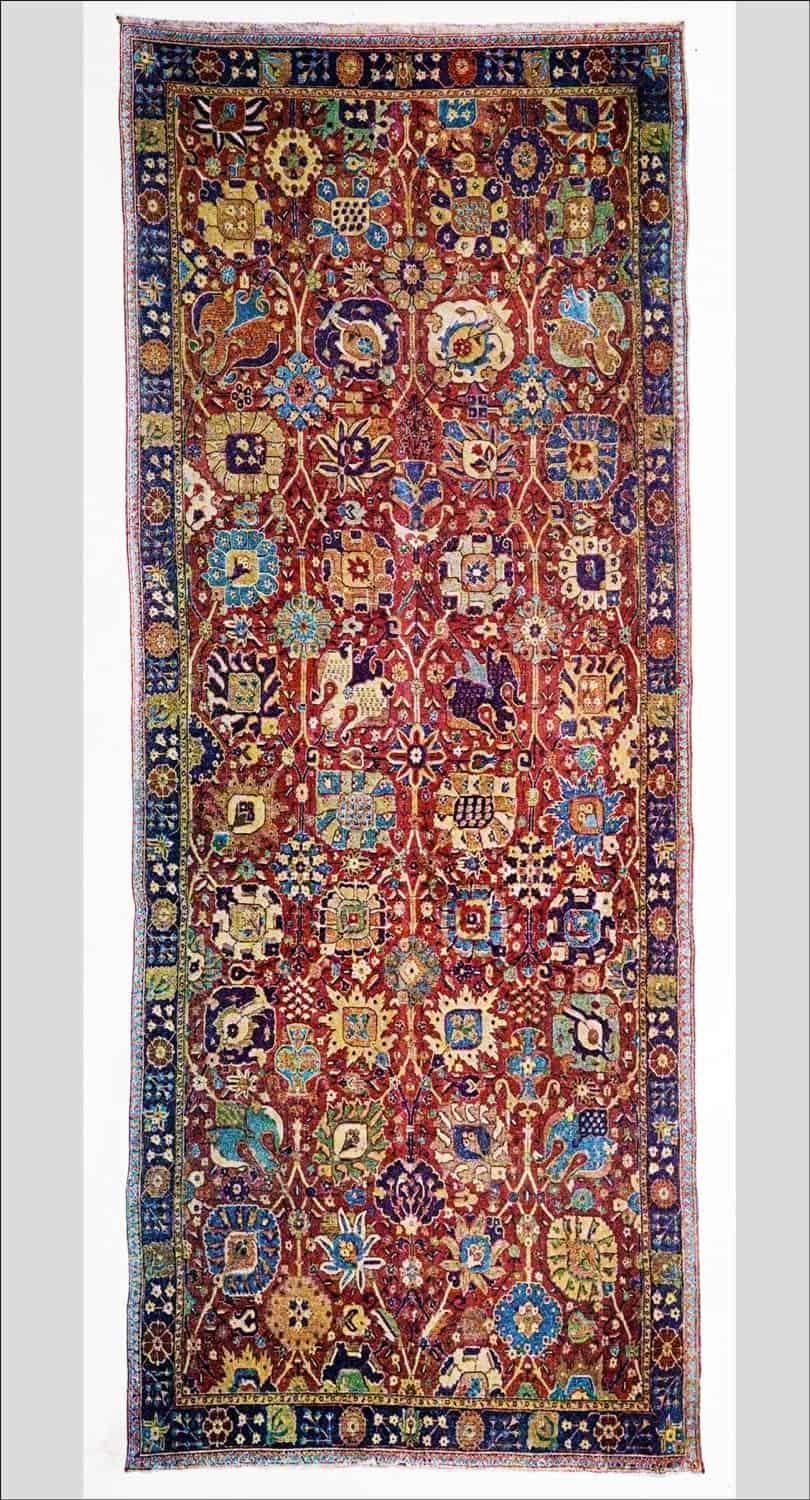

FIFTEENTH CENTURY ROYAL PERSIAN.

Length, 11 feet 10 inches; width, 6 feet 1½ inches.

600 hand-tied knots to the square inch.

From the Collection of the late Henry G. Marquand.

THIS is probably as near perfection as the woolen carpet of the East has ever come. It was a gift from the Emperor of the Persians, presumably to the Emperor of the Turks, for an authenticated record in the possession of its late owner set forth that the rug was among the effects of the Sultan Abdul Aziz of Turkey at the time of his death. The only pieces of this extraordinary character which have passed out of possession of the Oriental rulers and satraps who owned them are now locked in the treasure chambers of other princes, or displayed in the public or private galleries of Europe. In point of design this piece is closely kin to that owned by Prince Alexis Lobanow-Rostowsky, a reproduction of which in colors was published as Plate XI in the Vienna Museum’s work “Oriental Carpets.”

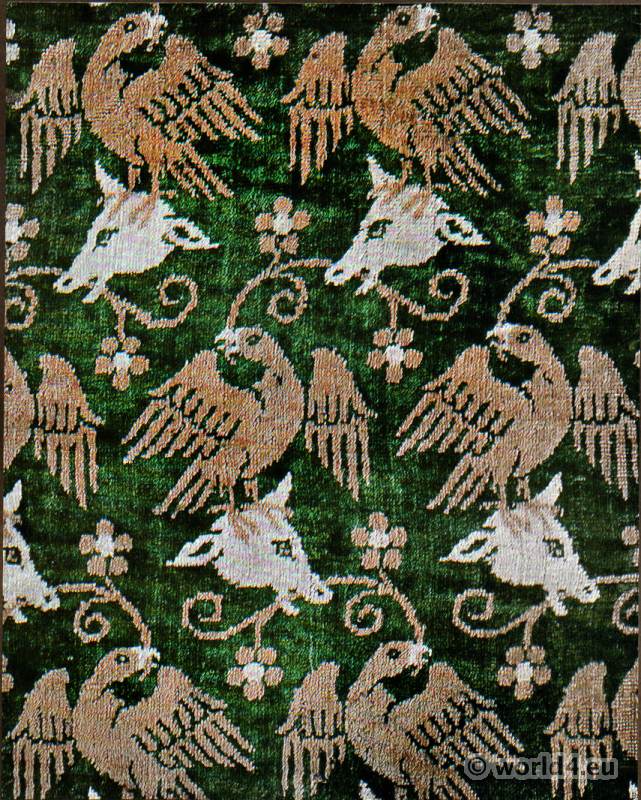

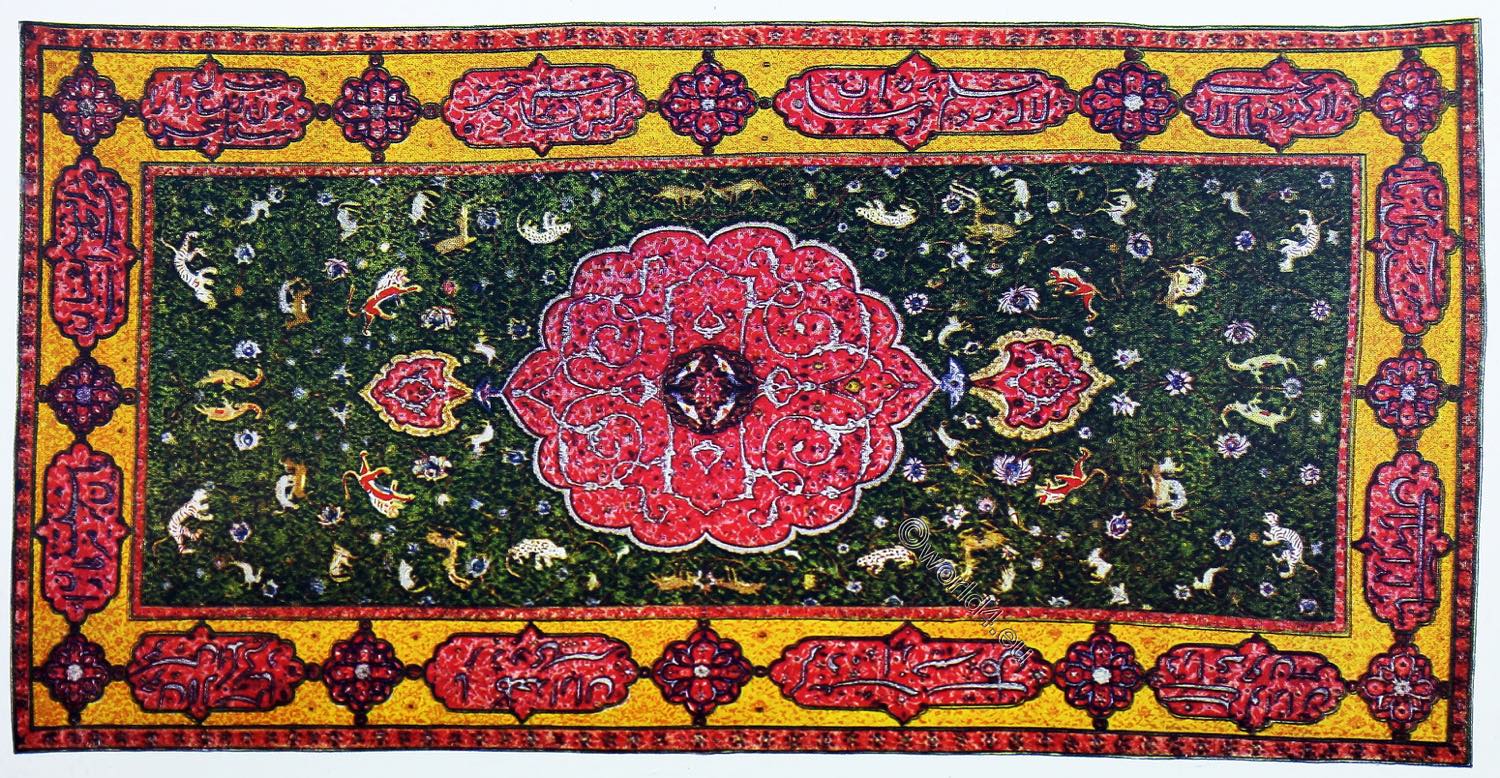

Beginning with the matter of color, there appears here in the medallions of both centre and border the uncommon shade of wine red which is found in Plate XI. The green, instead of being used as a ground color for the border, is applied to the production of a higher and infinitely more artistic effect. Upon a black central ground is spread, after the fashion of the Sufi times, a bewildering but perfectly balanced and coordinate display of moss-green creepers. The parent stems, which are the framework of the vine structure, are in a deep shade of orange, outlined with more pronounced red. Even these are slender and curved in the most graceful manner; but the green branches, leaves, tendrils, and even flower shapes which grow out from them, are of incredible delicacy and profusion. Here and there, at regular intervals, and in corresponding positions on both sides and ends of the field, are tiny natural flowers, in glowing colors, similar to those seen in such plenty in the Ardebil carpet (Plate XXII), save that in number and size they are reduced to a minimum in order not to distract attention from the more essential animal figures which inhabit the field.

In the centre is a medallion, with what for the sake of clearness may be termed” escalloped edges,” and depending from this, toward each end of the rug, though with no pretense at actuality, are the temple lamps. Medallion and lamp simulacra are both grounded in what has been called the Isphahan red, and upon this, in pink-a faint, unobtrusive, but withal beautiful contrast other fragile interwoven vine traceries.

This serves merely as a composite background for the superb arabesque design worked in silver thread, the pile yarns apparently having been omitted to allow the metal threads to be attached directly to the warp, in what closely resembles the Soumak or tapestry stitch. A very similar device is also found in the centre of the Ardebil carpet.

In the innermost space of the medallion, symmetrically grouped, are four birds, evidently of the hawk tribe, drawn with much skill and considerable veracity. Outside the medallion, disposed amid the green in the most lifelike attitudes of flight, pursuit, combat, etc., are the animals which play such prominent parts in the Moslem allegories. and which were, in fact, endowed with such large mythological significance by the peoples of Asia long before the rise of Mohammedanism. The profundity of meaning which attaches to these divers beasts, and even to their sundry attitudes and occupations, is hard to come at; but it is impossible to overlook the difference in posture and relation to one another between the animals in the Lobanow-Rostowsky rug and this. It is quite to be credited, too, that these changed attitudes and relationships, coupled with the wholly dissimilar color scheme, are meant to convey a different meaning, to depict another state of feelings, another stage in the progress of the endless contest between right and wrong that the animal entities are supposed to typify.

Without endeavoring to expound the beliefs of which the animal kingdom provides visible symbols, it will suffice to repeat that the beasts of prey generally represent light, victory, glory, right; and such as deer, gazelles, sheep, goats, and the like, the opposite. In the Lobanow-Rostowsky rug the central field is of a lighter color, verging on yellow, and corner spaces are formally set off, occupied by the heron and other birds. Here the corners are abandoned, and the birds included in the centre medallion, the heron, usually an emblem of long life, being omitted.

It should be noted that the birds ot the hawk tribe have been in all lands and ages suggestive of victory. The coincidences in color and design here are scarcely to be dismissed. They suggest much. The heron is left out; the hawks, which occupy the corner space in the other rug, are here transferred to the centre of the carpet. The backs ground is laid in funereal black, but traversed and overspread with the nascent green which is emblematic of renewal, perpetuity, and great spiritual joy.

Thus, without translating the inscriptions on the rug, which will be referred to later on, there is a suggestion of death, coupled at the same time with repeated symbols of victory, and a suggestion of fierce prosecution of the endless struggle between right and wrong, light and darkness.

But the contest as figuratively set down in this carpet seems to have progressed to the point of partial conquest, since the panther has captured the fawn and bears it down, whereas in the Lobanow-Rostowsky rug the movements of pursuit and flight among all the animals seem to have just begun. Jackals still follow the track of the deer; the leopard, a bold and fierce figure crouches in his thicket of green, ready to spring upon the he-goats, warring powers of evil. The huge red lion, Persia’s own symbolical beast, an element not shown in the other rug, roars on the trail of the spotted stag, which turns, terrified. In deep thickets, close to the lairs of lions and leopards, the timid rabbit hides in dread, or elsewhere takes refuge in flight.

Yellow has in all ages been expressive of joy and victory. It is royally displayed in the broad borders of the rug, overspread with fine vine patterns in a monotone of orange. In the border of the Lobanow-Rostowsky rug there are, all told, six cartouches, grounded in black, of the same shape as those found in the Ardebil carpet, and joined by escalloped medallions in the same manner. But here there are twelve of these cartouches, instead of six, and they have a ground color of the Ispahan red, inlaid with pink vines, similar to the medallion in the centre. Again the idea of immortality is to the fore, as that is the ordinary significance of the cartouche.

Thus, from first to last, in spite of the black centre which suggests a mourning carpet, there is the note of triumph, joy, and immortality. In view of the intermittently hostile relations maintained between Persia and Turkey during the era when the rug was unquestionably made, all that is to be read in its design is most vital, and seems expressive of some phase of history, which was then making so vigorously.

Whatever temporal significance the carpet may have borne, as a gift from one monarch to another, the general interpretation outlined in the foregoing is amply sustained by the inscriptions in the border, a most sympathetic translation of which has been made by Dr. Richard J. F. Gottheil, of Columbia University. With his permission it is here given.

O Saki, the zephyr of the Spring is blowing now;

The rose has become fresh and luxuriant.The drops of the dew are like pearls in the cup of the tulip,

And the tulip unfolds its glorious flag.Narcissus keeps its eye on the stars,

Like the night-watch throughout the night.To sit alone in the desert is not

Isolation with the company of wine.When Saki passes the beautiful cup around

The rosy cheeks of the beauties becomeViolet for the love of the rose,

And look like the purple robe of a horseman.

The lines, though it is difficult to locate them precisely, are, like nearly all the inscriptions found in Persian fabrics of whatever age, a quotation from one of the poets of that most poetical of all eras, and perfectly illustrative of the high artistic impulse which centuries of war, pillage, gradually waning power and swiftly increasing poverty and suffering have failed to eliminate from the Persian nature.- From the Author’s Notes as set down in the Catalogue of the Marquand Collection.

Source: Oriental rugs by John Kimberly Mumford. London, Sampson Low, Marston, 1902.

Continuing

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.