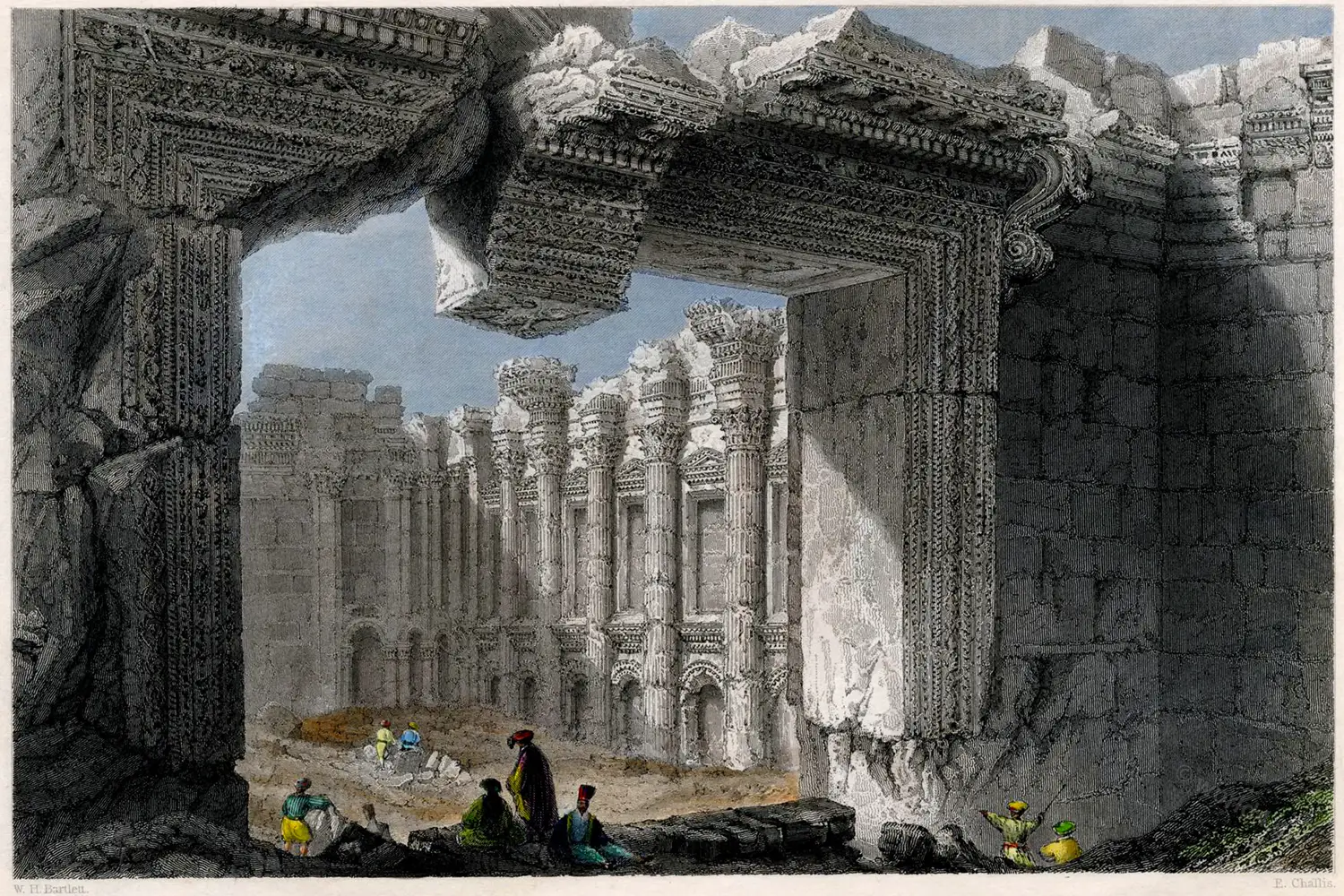

Interior of the Great Temple at Baalbek.

The road from Damascus to the ruins of Baalbek, is full of interest: at times wild and rocky, and again beautiful and well cultivated; a few villages, charmingly situated; and the refreshing voice and sight of rapid streams the whole way. In seeking Palmyra, the traveller hastens through a hot and thirsty land, where no oasis in the desert induces him to linger, or his excited imagination to pause; yet it may be, that the privations and weariness these ruins require, render them more precious to the eye.

The visit to Baalbek is rather a beautiful promenade, with enough here and there of the savage to give it a startling variety. The position of the ruins is very favourable to their effect: on the plain in which they stand, scarcely any trees are visible, but near the temple there is a little grove of the walnut, the willow, the poplar, and the ash: the long range of the Anti-Lebanon Mountains rises near. The small town of Baalbek, whose white thin minarets contrast singularly with the dark mass of enormous ruins, is on an eminence adjacent.

It is in truth a world of ruins, a solitary and sacred world, where the wild Arab and his hordes do not dwell, as in Palmyra, which the hand of the stranger does not desecrate, as in Egypt: the people who dwell around are a peaceful, pastoral people: the sun, the deity to whom the temple was built, seems still to linger there with a fiercer glory; his first and latest purple beams fall on the mournful ruins, which, like the lone sepulchres of the Arabs in the desert, shall not yield their prey, or bow their heads, till the last trump shall sound.

Many a day, many a week may pass, ere curiosity is satiated, or interest wearied at Baalbek. Are you wearied with ranging along the walls of marble, the richly ornamented arches, the marble doors of colossal dimensions, the granite stones in the outer walls that needed almost a nation’s strength to place where they now stand: then sit down on this fallen shaft or capital, it is evening, the Arab brings the pipe, and twilight, the fleeting and precious twilight of the East, is stealing over the ruins.

Oh beautiful and memorable moments, on which there is no sound save the fall of the stream over the buried sculptures and friezes, its white foam and its little lakes floating through the mysterious light; that light is fading fast on the awful ruins. Time, they are thy voice, thy majesty! not the angel who shall place one foot on the shore, the other on the sea, can speak a more thrilling message than these—of the lost nations who toiled here, each for immortality—the Indian, the Egyptian, the Hebrew, the Greek, the Roman, have here lavished all their energies and skill; each gloried and sank in turn, availing themselves of the precious labours of each other.

Some of the stones are cut exactly like those in the subterranean columns at Jerusalem: the similarity of the workmanship strikes so forcibly, as to warrant the referring them both to the same people, and nearly to the same era; compared with many other parts of the building, which are decidedly Roman, they most probably belong to the remote period of eight-and-twenty hundred years ago, the era of Solomon king of Israel and Judah, who built Hamath and Tadmor in the desert.

“The second builders of this enormous pile have built upon the foundations of their predecessors; and in order that the appearance of the whole might seem to be of one date, they have cut a new surface upon the old stones; so that the different eras of the building are often exemplified in the same colossal stone.” The is sunk into the twilight night, the stars are faint on the mountain’s breast, and fainter on the temple, whose depths and recesses they cannot penetrate: now wander forth around the lonely places: the Arab is gone to his rest, his watch-fire is dimly burning beneath the wall, and his white cloak covers the sleeper like a shroud: what to him is the magnificence of past ages, or the generations who laboured and died here! could they rise, the many thousands of remotest times and nations, from their rest beneath their mighty works, their mingled wail would be more sad and full of anguish than his own funeral cry over the desert tomb of those he loved.

The mass of the grand temple, in the form of an irregular square, is at the extreme left, and below it the little octagon building of marble, with marble columns of the Corinthian order; the six noble columns in the foreground are more particularly described in a succeeding plate: the more perfect edifice in front is the second temple.

Source: Syria, the Holy Land, Asia Minor illustrated in a series of views drawn from nature by John Carne, William Henry Bartlett, William Purser. Published by Fisher Sons & Co. London, Paris & America. c. 1836.

Related

- The Temples of Baalbek in Lebanon.

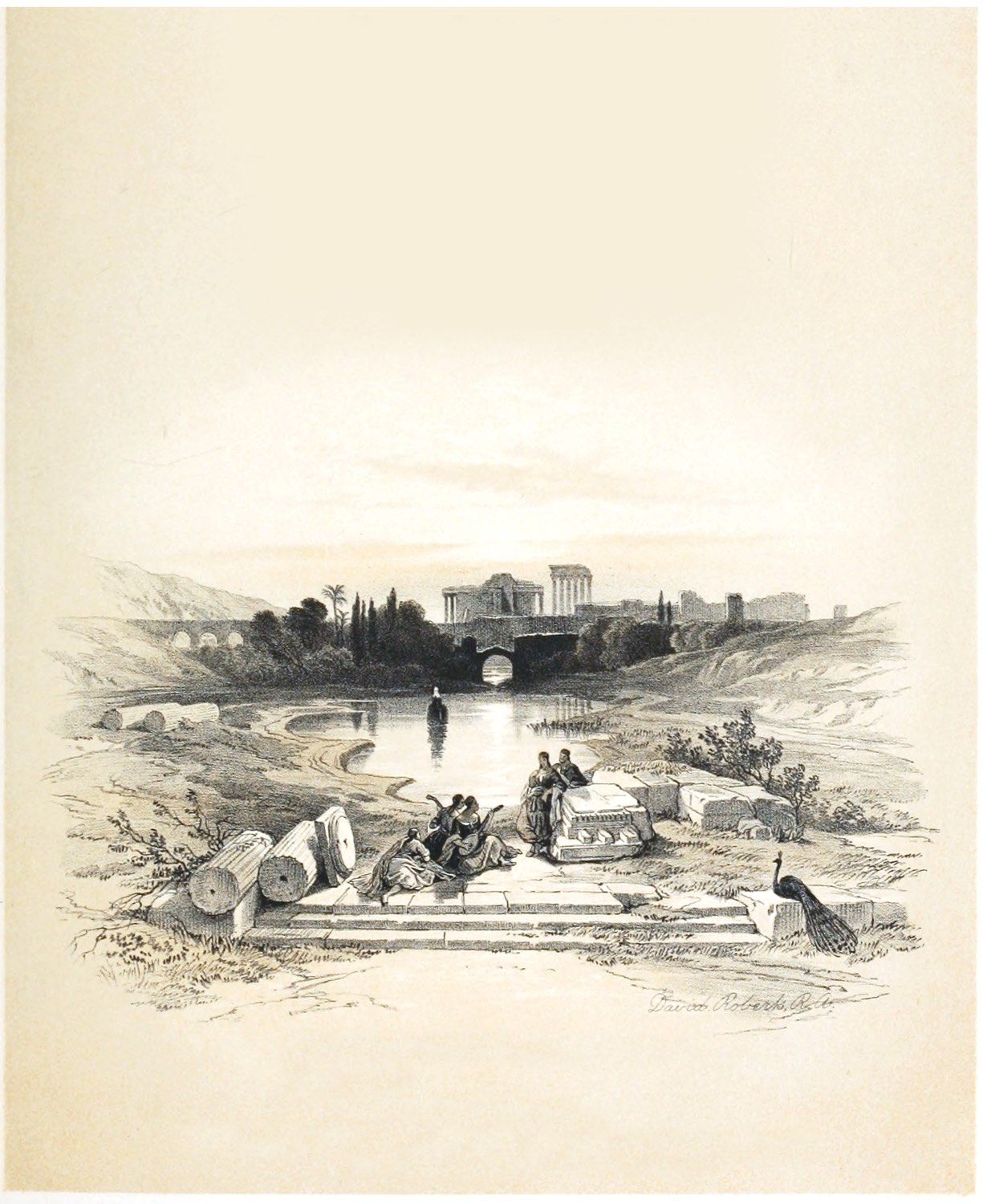

- Baalbek from the Fountain May 7th 1839.

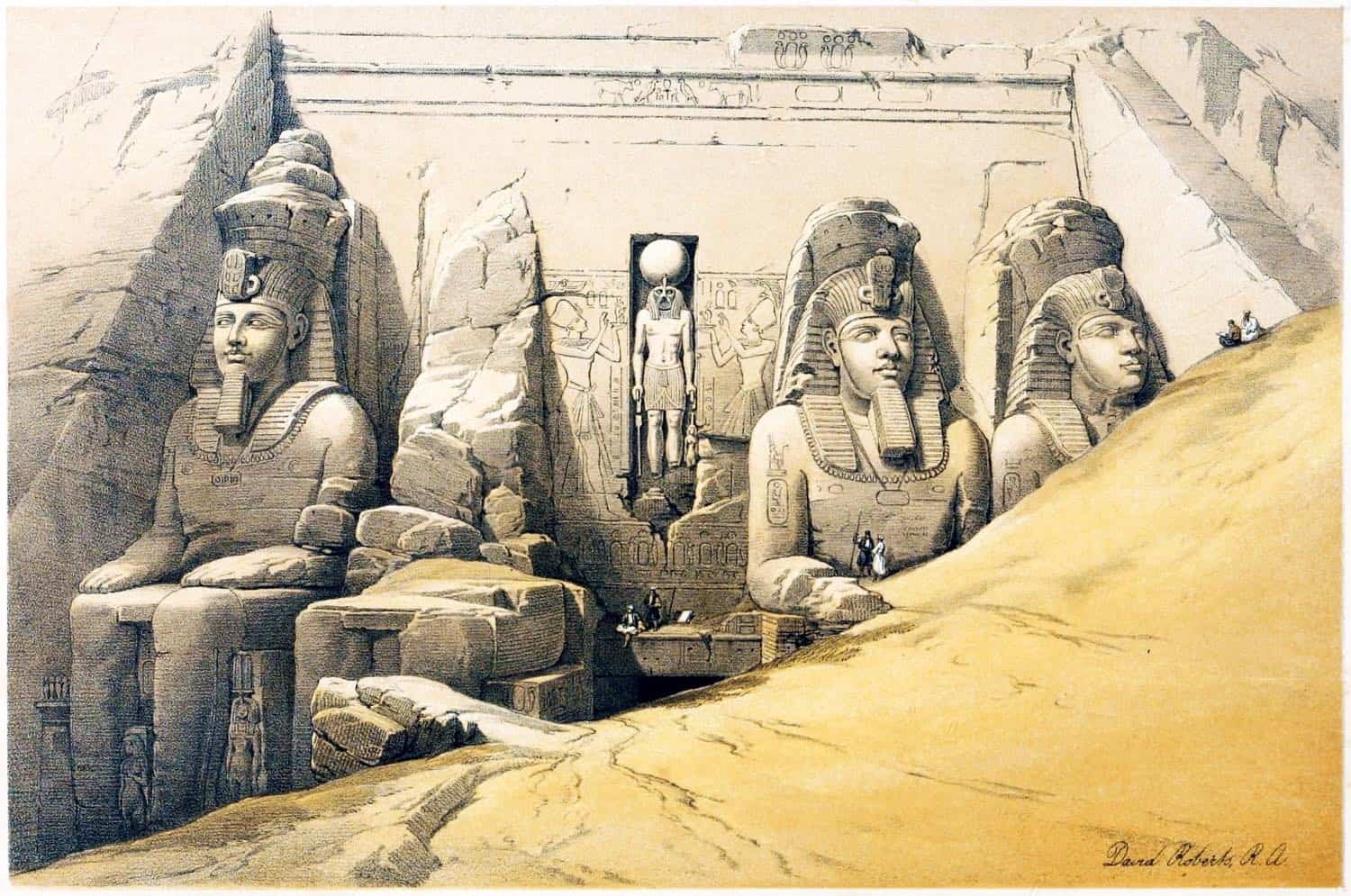

- The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, & Nubia by David Roberts.

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.