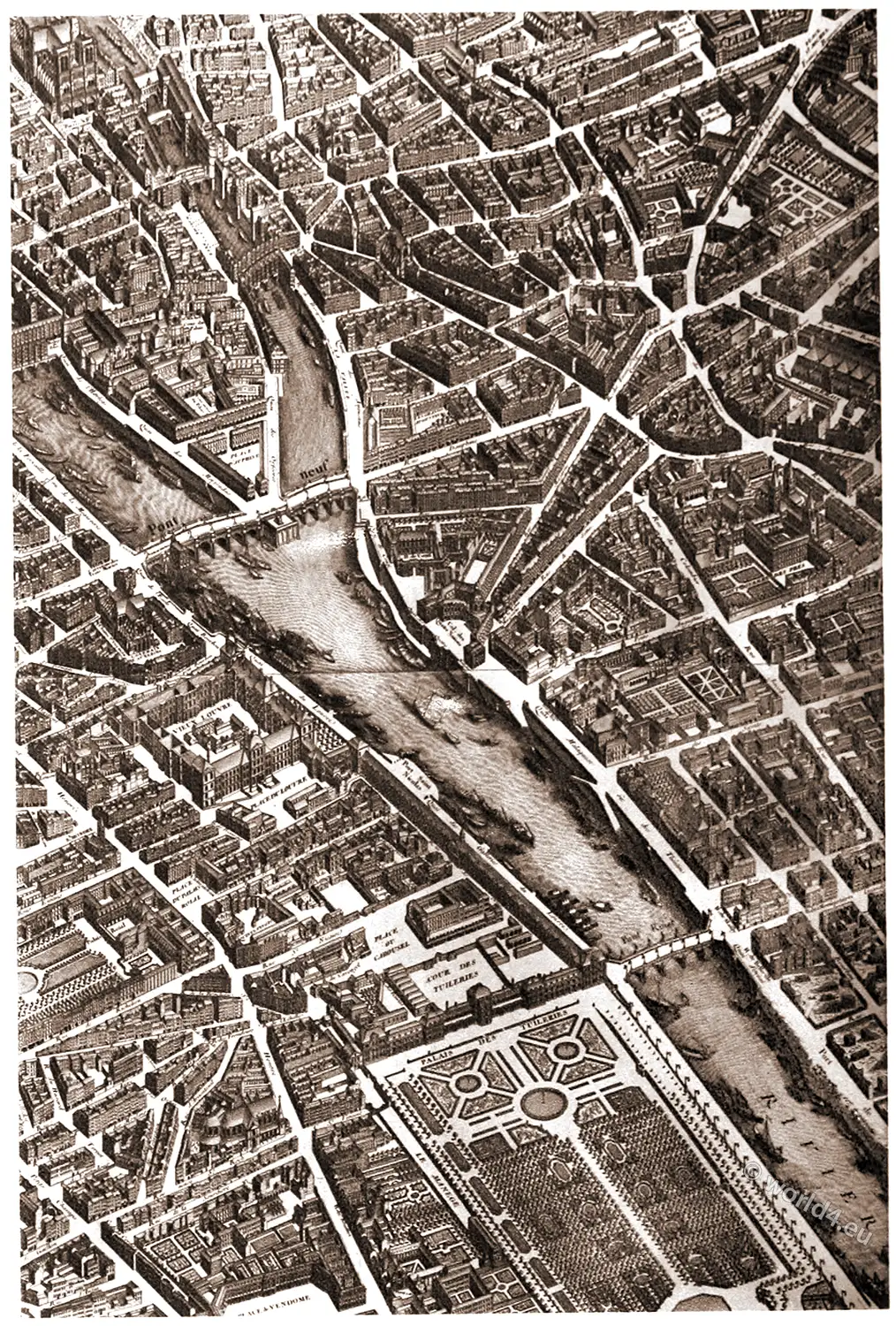

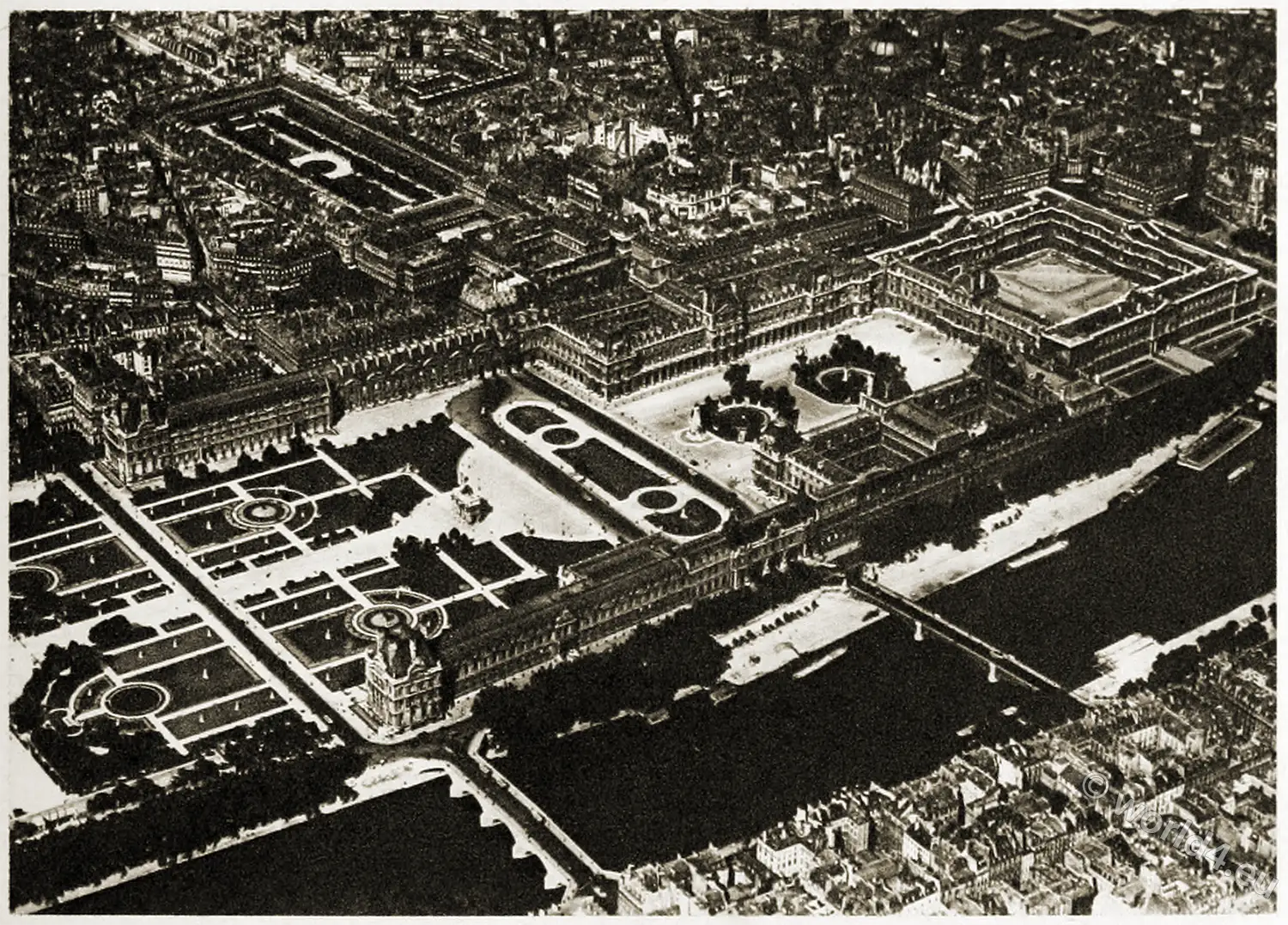

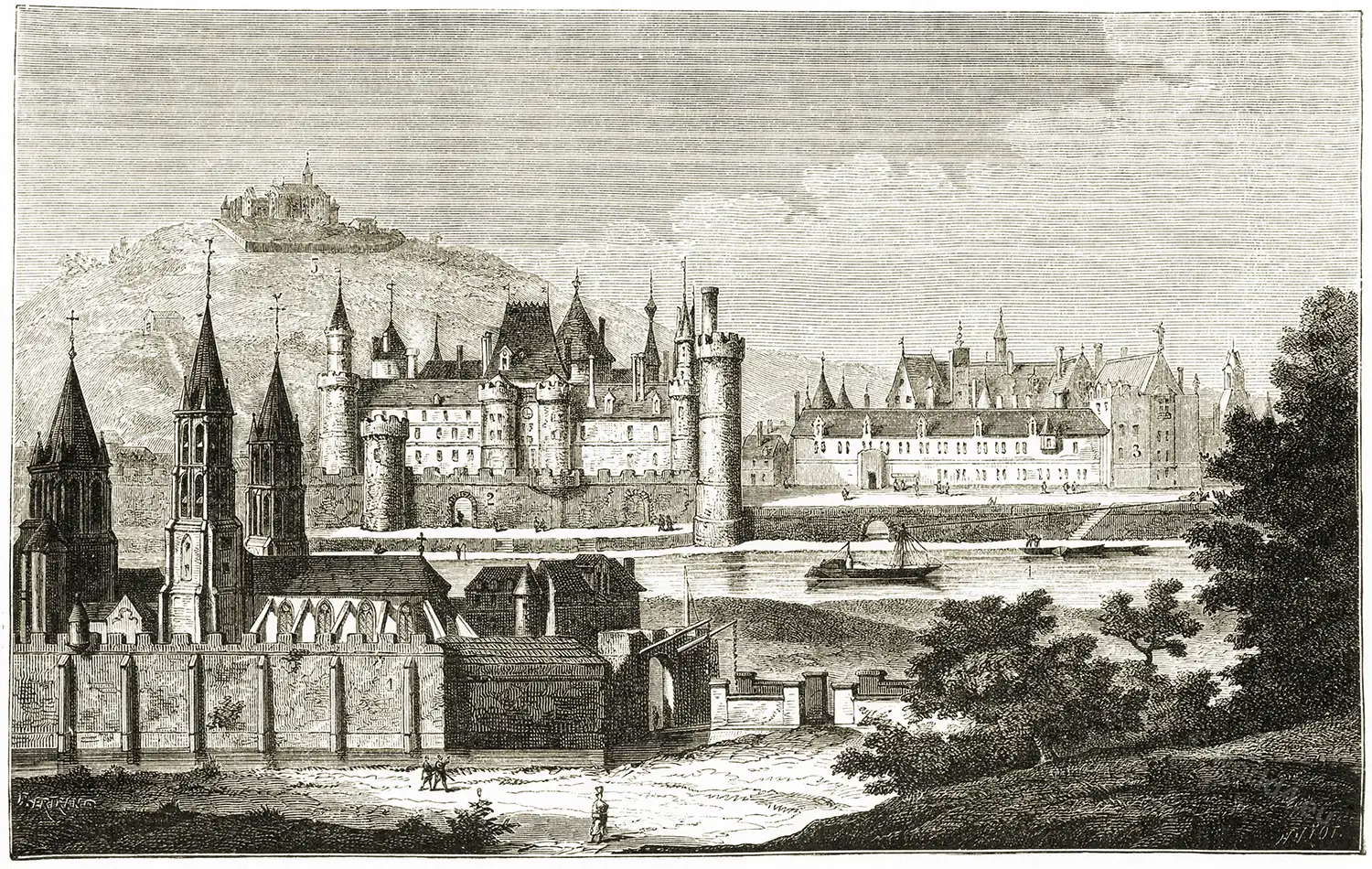

The palaces of the Louvre and Tuileries at Paris.

The palaces of the Louvre and Tuileries, now united, once separated by a whole quarter of Paris, are of absorbing interest as the central residence of the French monarchies from the sixteenth century to their final disappearance, with the exception of a little over one century, when the glories of Versailles cast them into the shade.

The history of their growth, union and decoration, illustrates almost every phase of architectural fashion since the establishment of the classical Renaissance in France. In the accompanying plates we may see that classical Renaissance in its earliest bloom in the Louvre of Pierre Lescot and Jean Goujon, and in a stage of expansion, but of temporary decline in taste in the Tuileries of Philibert de l’Orme.

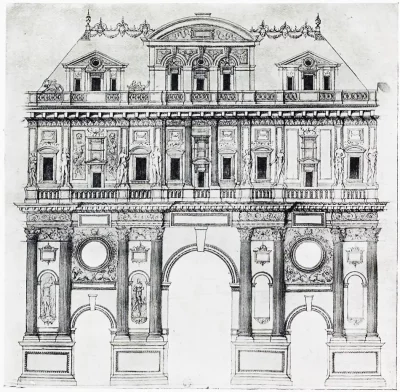

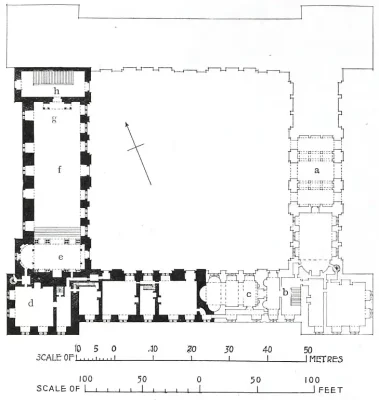

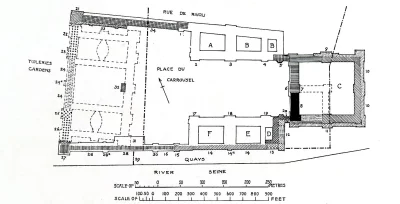

References to Figure 13.

a Intended Entrance Pavilion.

b Intended Second Staircase (?).

c Intended Chapel(?).

d King’s Chamber.

e Dais.

f Guard Room.

g Minstrels’ Gallery.

h Main Staircase.

The parts blacked in are those built between 1546 and 1576, the remainder is conjectural. This plan is based on du Cerceau, viz. : D.I. 1, 2, 3, 4, with description. B.M.I. 1 and 2, and the drawing reproduced in fig. 16, which is a design made by him for the entrance. A chapel with three apses seems to be suggested on the ground floor by D. I. i, r. h., at the point where the plan breaks off.

The first floor plan, D. I. 1, r.h., extends further east, and shows a rectangular chamber at this place. Du Cerceau says the building was carried to the point where a second staircase was to be placed, viz., probably the projecting bay next the s.e. angle, corresponding with the first stair next the n.w. angle. The start of a passage seems also to be indicated, which would run past the chapel and give access to the stairs and s.w. pavilion.

The history of the complex buildings now or once forming part of the united palaces of the Louvre and Tuileries falls into three main divisions :—-

I. The Louvre proper, i.e. the buildings enclosing the square eastern court.

II. The Tuileries proper, i.e. the western range of buildings occupying the space between the Pavilion de Marsan (21) on the north and the Pavilion de Flore (27) on the south.

III. The junction of the two palaces. This division itself falls into two parts each again subdivided into two, viz.:

- The Greater Louvre, i.e. the buildings thrown out from the Louvre westward principally with a view to joining the two palaces:

(a) Along the river.

(b) Along the Rue de Rivoli. - The Greater Tuileries, i.e. the buildings thrown out from the Tuileries eastward with a view either to the completion of the original scheme of that palace or to a junction with the Louvre:

(a) Along the river.

(b) Along the Rue de Rivoli.

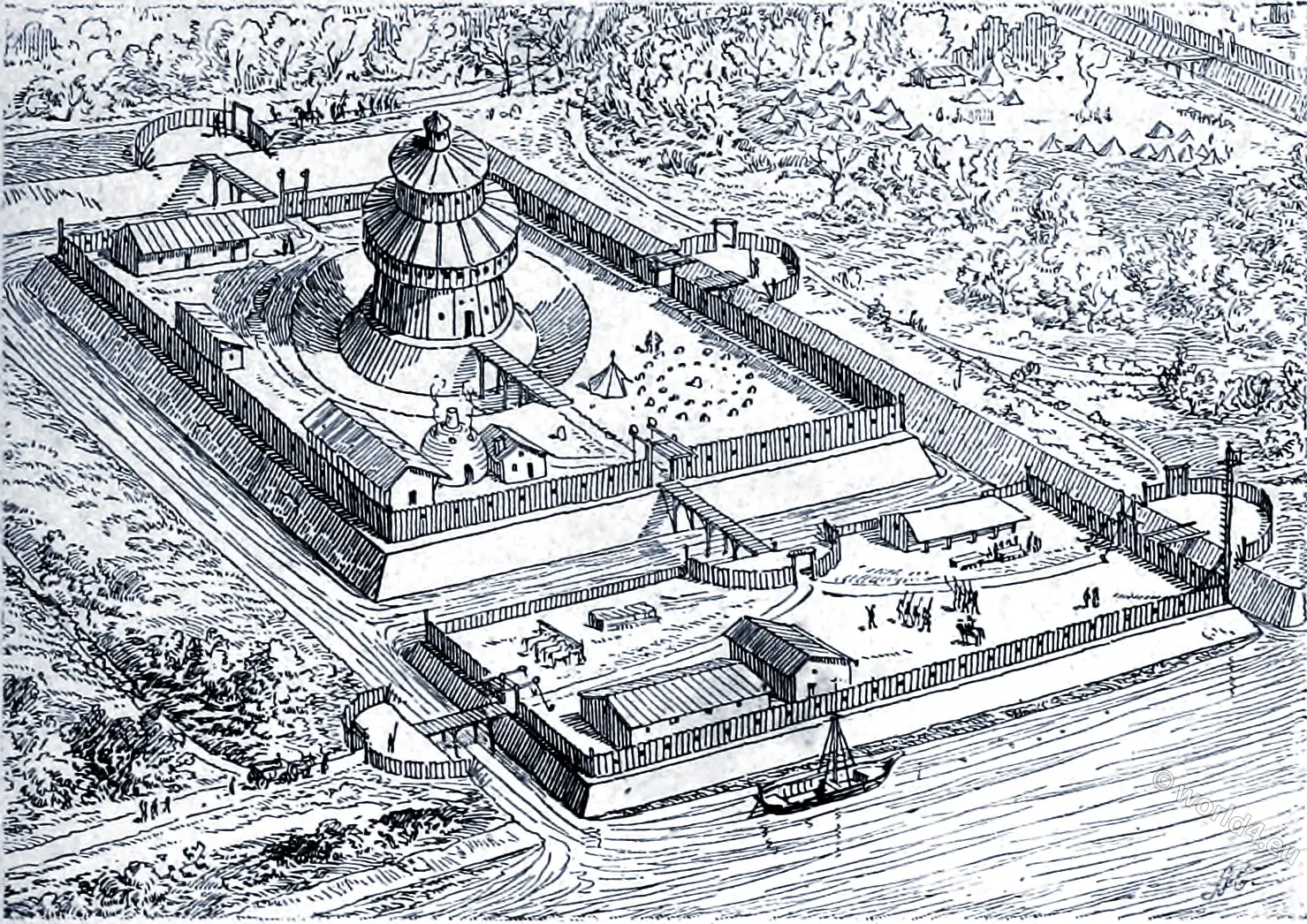

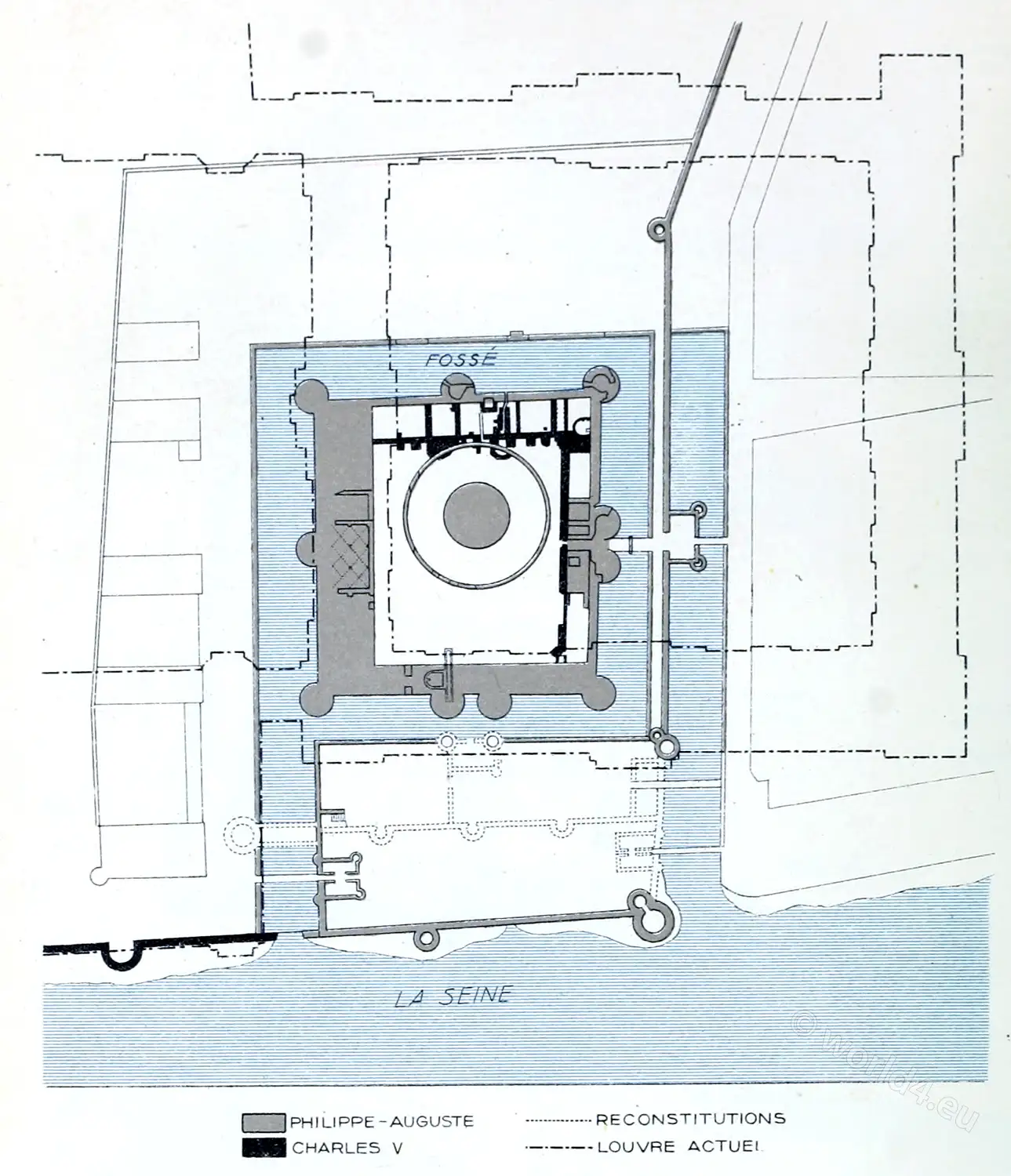

In studying the history of the palaces their position in relation to the successive “enceintes” of the city should be kept in mind. The original Louvre was built outside the walls of Philip Augustus. 2)

1)The references in small letters are to fig. 13; those in figures and capitals to fig. 14.

2) Built 1190-1210, indicated thus in fig. 14.

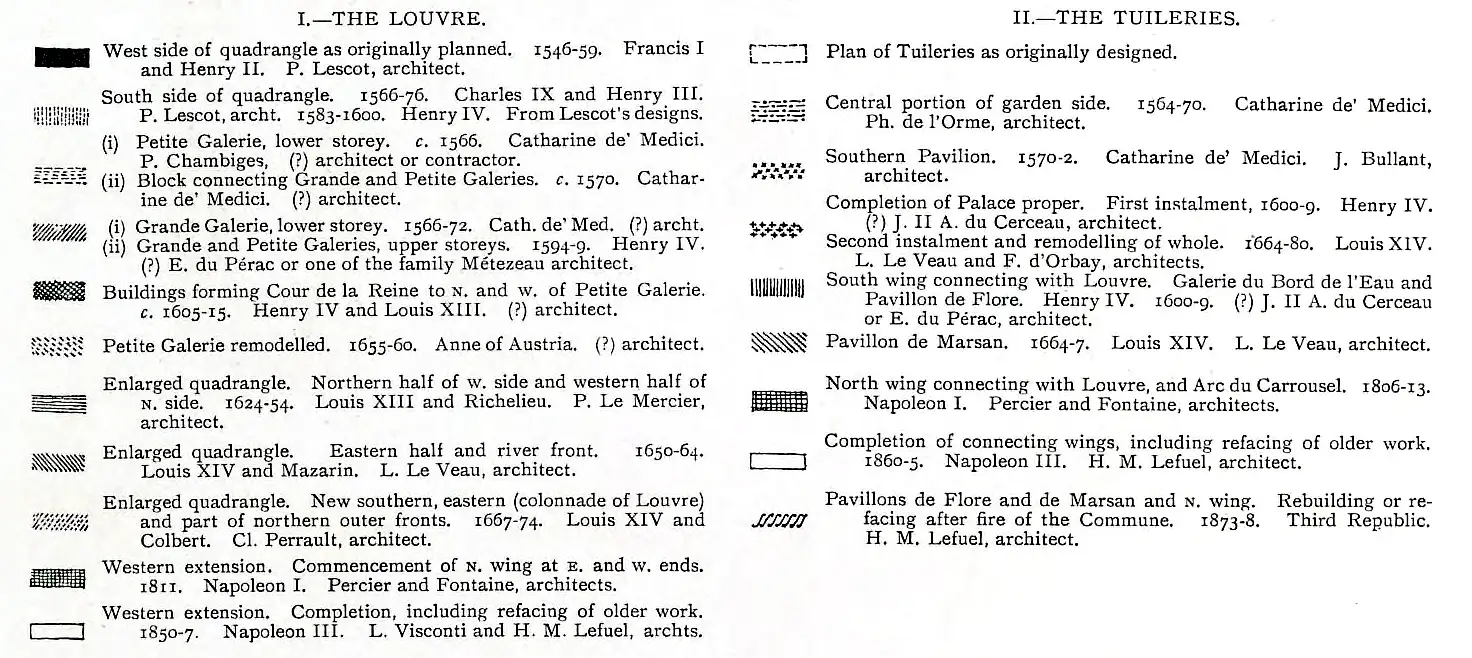

References to Figure 14.

I. – THE LOUVRE.

1 Pavilion de Rohan.

2 Pavilion Turgot.

3 Pavilion Richelieu.

4 Pavilion Colbert.

5 Block by Percier and Fontaine.

6 Pavilion Sully

7 Pavilion de l’Horloge

8 Block by P. Lescot.

9 Pavilion Marengo.

10, 10 Colonnade of the Louvre.

11 Pavilion des Arts.

12 Petite Galerie.

13 Salle des Antiques.

14, 14 Grande Galerie.

14a Porte Jean Goujon.

15 Pavilion Lesdiguières.

16 Guichets des Sts. Peres.

17 Pavilion Mollien.

18 Pavilion Denon.

19 Pavilion Daru.

20 Position of Bridge Gallery from Louvre to Petite Galerie.

II. – THE TUILERIES.

21 Pavilion de Marsan.

22 Wing by L. Le Veau.

23 Pavilion by L. Le Veau.

24,24 Wings by Ph. de l’Orme.

24a Central Pavilion.

25 Pavilion by J. Bullant.

26 Wing by J. du Cerceau (?).

27 Pavilion de Flore.

28, 28 Galerie du Bord de l’Eau.

29 Site of Porte Neuve.

30 Pavilion La Trèmoïlle.

31 Salle des Etats.

32 Arc du Carrousel.

33 Façade by H. M. Lefuel.

34 Wing by Percier and Fontaine.

The Louvre when its rebuilding began stood inside the wall of Charles V. *) The Tuileries were built outside this wall and were long virtually unprotected, since the new walls outside it begun by Henry II, and continued by Charles IX (1563-6), were not completed till the reign of Louis XIII (1633-6). Ten years later they were abandoned as fortifications and turned into a public promenade.

*) Built 1367-1383, indicated thus in fig. 14.

I. THE LOUVRE PROPER.

The Louvre 1) has many analogies with the Tower of London, of which indeed it was an imitation. Its site was similar, adjoining the walls of the capital on the outside at a point where they met the river. Like the Tower it was the fortress, arsenal, state prison and treasury, as well as the residence of the kings.

Founded by Philip Augustus in 1204, the castle occupied about one quarter of the area of the present quadrangle, 2) and consisted of a square court flanked by ten round towers with an isolated circular keep in its midst. 3) It was surrounded by a moat and separated from the Seine by a base court and a road, both defended by further walls and towers.

Several kings left their mark on the Louvre, notably Charles V, who built the north and east facades of the court and a magnificent spiral staircase (1365), designed by Raymond du Temple.

1) The name is first mentioned in 1189. Its origin is quite uncertain.

2) The position of its buildings is marked by lines in the pavement.

3) The “Tour,” or “Grosse Tour du Louvre,” from which all fiefs in the kingdom were held.

After the Hundred Years’ War the Louvre, like the Tower of London ceased to be the regular residence of royalty. 1) Little alteration took place in it till the reign of Francis I, who, after first destroying the donjon, which darkened the court (1527), and redecorating the interior 2) (1539), decided to rebuild it. It is said 3) that a competition for the design of the new palace was held (1543), and that Serlio 4) advised the king to accept Lescot’s 5) desions as superior to his own.

1) It was abandoned in favour of the palaces of “St. Pol” and the “Tournelles.”

2) In view of the visit of the Emperor Charles V.

3) By Claude Perrault.

4) Sebastiano Serlio, b. 1475, d. 1552.

5) Pierre Lescot, b. c. 1510, d. 1578.

Be this as it may, Lescot was appointed architect and conducted the building till his death (1546-78), with the collaboration of Goujon 1) (1549-62)and other sculptors. The new building was to form a square court covering approximately the same area as the old, viz., 175 feet square, and presumably 2) to have pavilions at the four angles (figs. 13 & 15), wings of two storeys and an attic on three sides (pl. 17), a lower wing containing the entrance (fig. 16) on the east (see dotted lines on fig. 13).

1) Jean Goujon, b. c. 15×0, d. bef. 1564.

2) Lescot s drawings, still in existence in 1624, have since been lost.

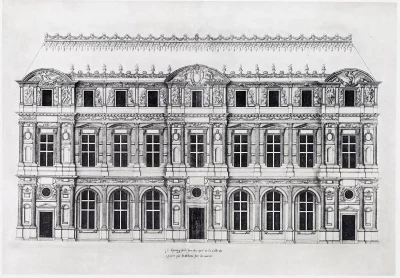

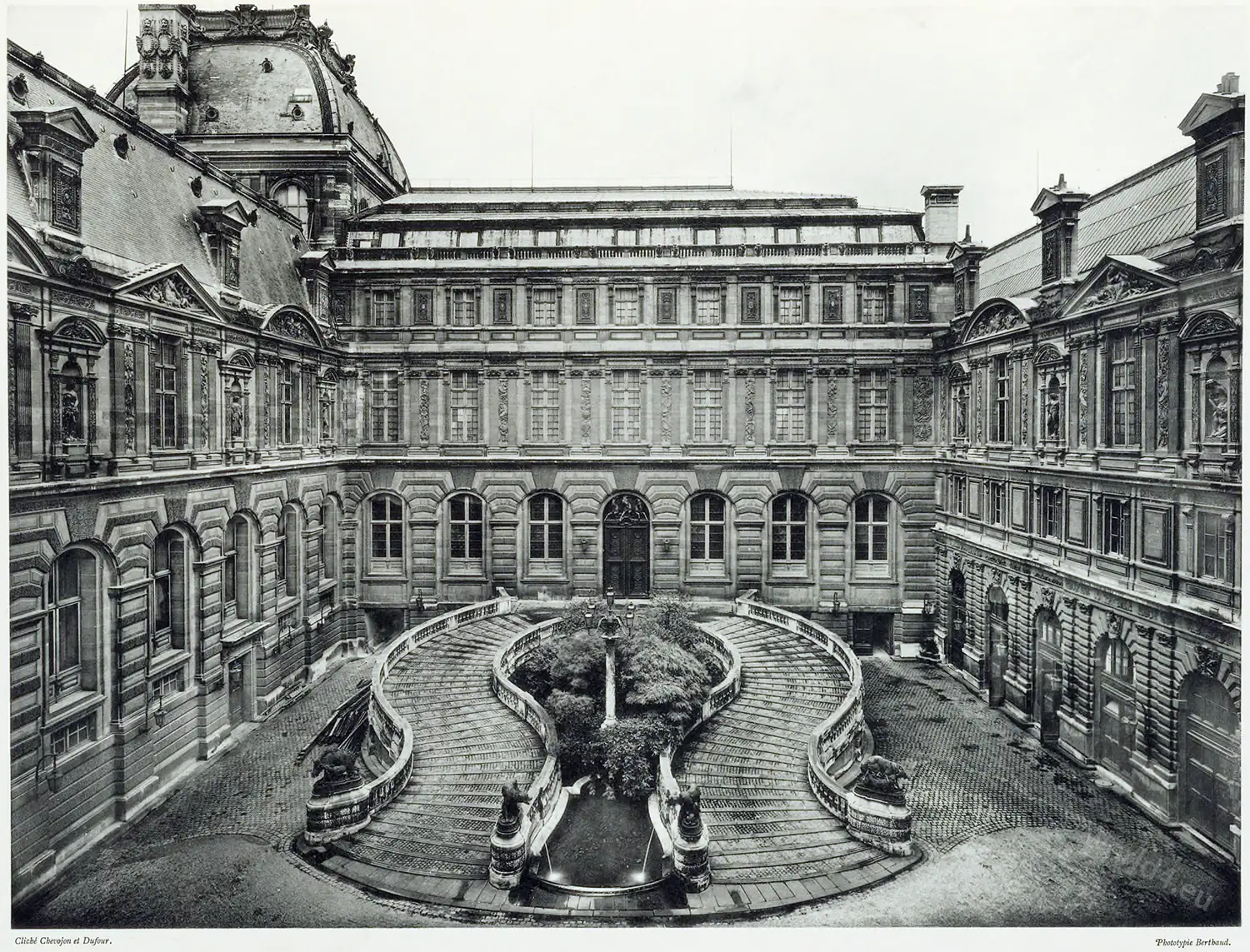

The west side (8, also pl. 17), begun by Francis, was built principally by Henry II, who also began the south wing. This was continued by his sons 1) and completed by Henry IV. Under Louis XIII and by Richelieu’s orders the building was resumed on an extended scheme, which more than doubled the length of the sides and quadrupled the area of the court, making it 410 feet square (1624-54).

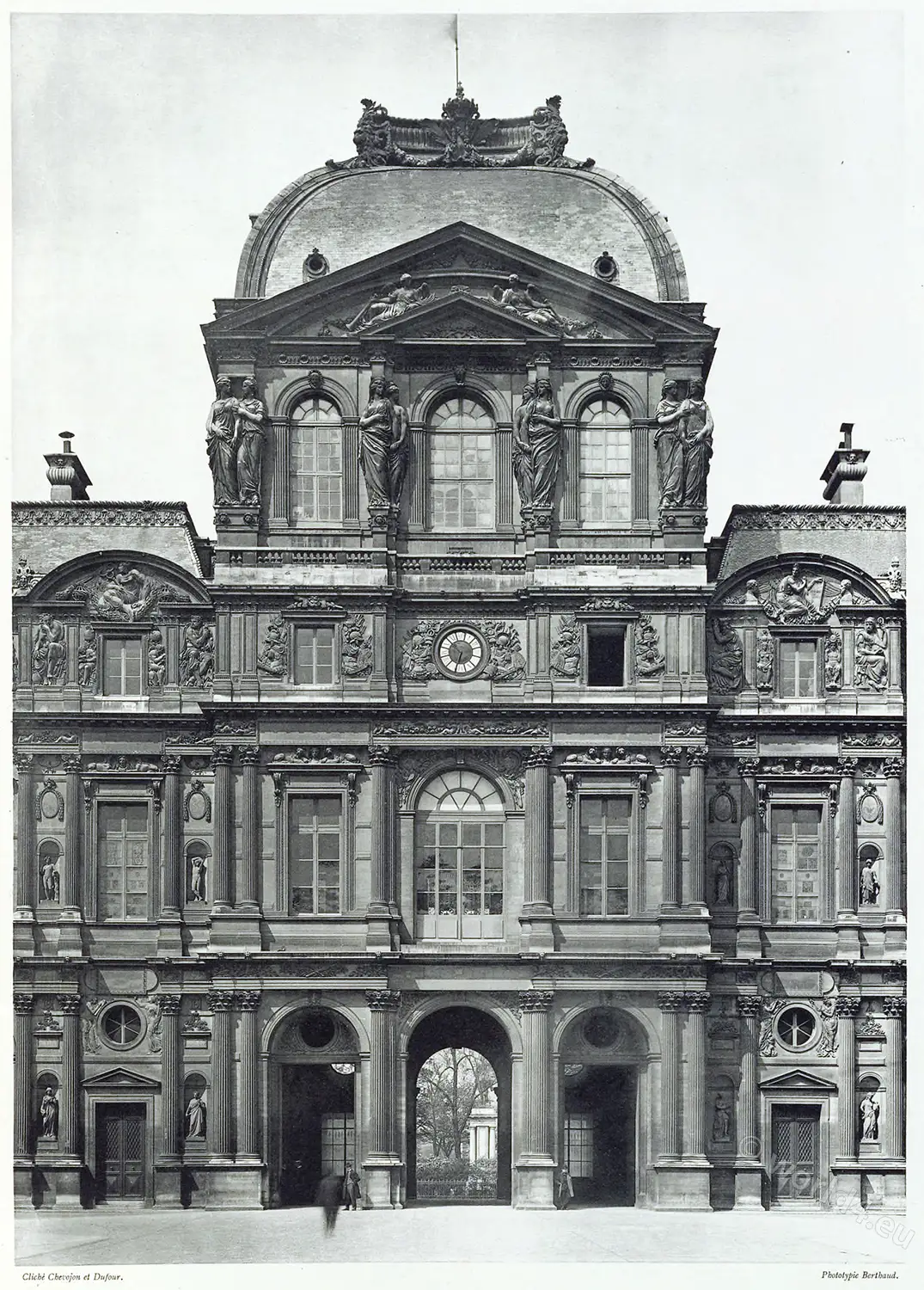

PAVILION SULLY. Overall view of the façade on the courtyard of the Louvre. Formerly the Pavillon de l’Horloge, built by Jacques Le Mercier during the reign of Louis XIII. PAVILLON SULLY. Vue d’ensemble de la façade sur la cour du Louvre. Ancien pavillon de l’Horloge, construit par Jacques Le Mercier, sous le règne de Louis XIII.

Pavilion Richelieu. Overall view of the façade on the Carrousel courtyard. Built by H.-M. Lefuel, under Napoleon III. Pavillon Richelieu. Vue d’ensemble de la façade sur la cour du Carrousel. Construction de H.-M. Lefuel, sous Napoléon III.

The architect was Le Mercier, 2) who prolonged the west wing northwards by adding a replica of Lescot’s facade and intercalating in the centre a pavilion of his own (6, 7) (“Pavilion de l’Horloge” or “Sully”), and began the return wing on the north. The work was continued under Louis XIV and Mazarin by Le Veau, 3) who completed the quadrangle internally and the south outer front (1650-64), following substantially the lines laid down by Lescot and Le Mercier.

1) Under Charles IX du Cerceau seems to have made a design for a chapel for the Louvre, near the river, which was not carried out.

2) Jacques Le Mercier, b. 1590, d. 1654.

3) Louis Le Veau (Vau), b. 1612, d. 1670.

Colbert, who became superintendent of the royal buildings in 1664, and in whose opinion Le Veau’s elevations for the east or entrance front 1) were not sufficiently imposing, obtained other designs. 2) These, however, proving equally unsatisfactory Bernini, 3) then at the zenith of his fame, was consulted and eventually sent for from Rome.

1) Illustrated in Blondel’s Architecture Française.

2) Illustrated in Blondel’s Architecture Française.

3) Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini, b. 1598. d. 16S0.

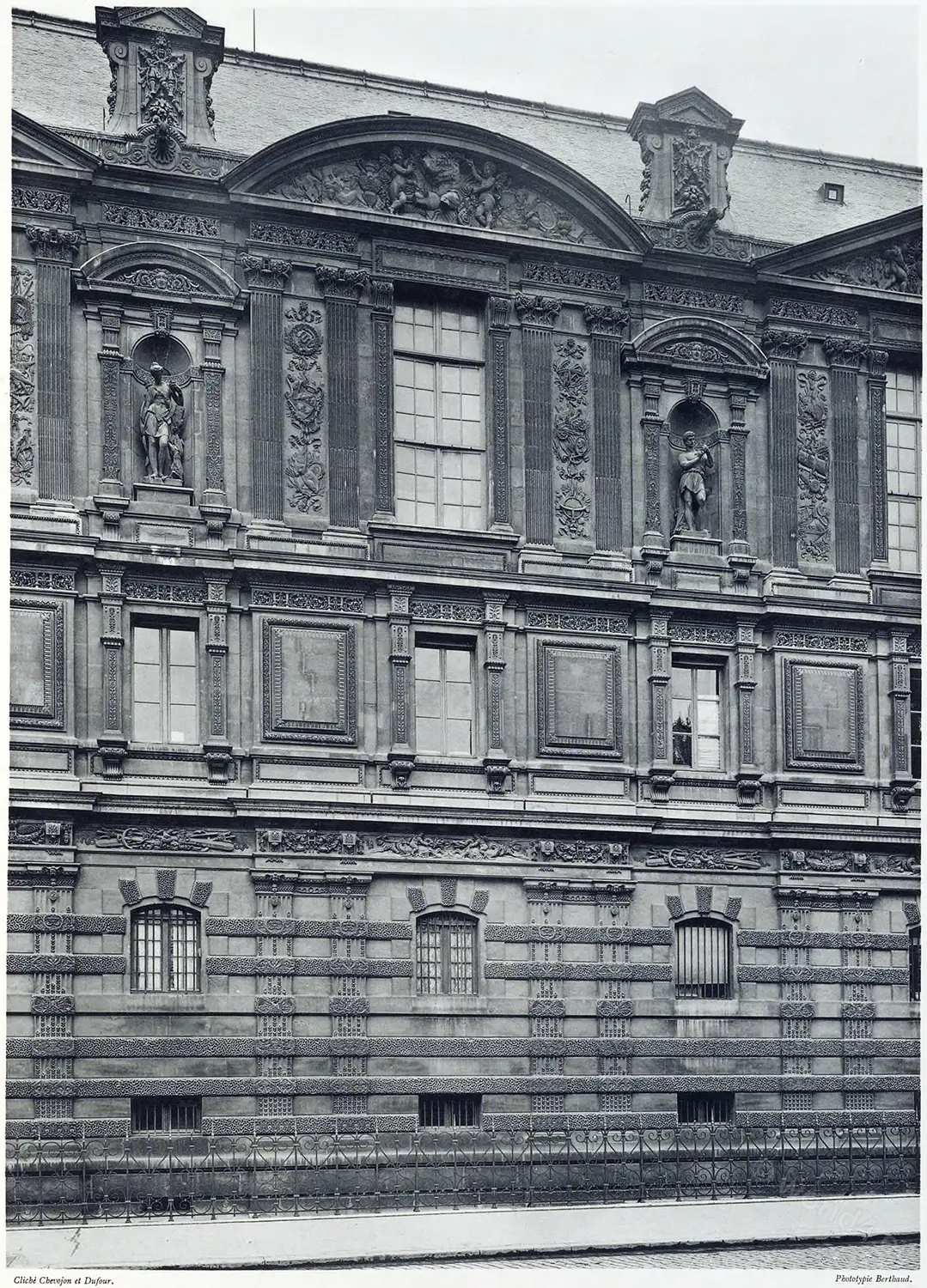

COUR DU LOUVRE. View of the south-west corner. Built by Pierre Lescot during the reigns of Henry II and Charles IX (the upper floor of the south façade is later).

COUR DU LOUVRE. Vue de l’angle sud-ouest. Constructions de Pierre Lescot, sous les règnes de Henri II et de Charles IX. (L’étage supérieur de la façade sud est postérieur.)

Received with all but royal honours (1665) he produced a new and grandiose scheme, which though on a vast scale was merely an example of the “forcible-feeble” and abounded in shams. Though the work was actually begun the Italian’s inordinate pretensions and the defects of a design 1) which involved the obliteration of almost all that had preceded it without providing the desired accommodation produced a reaction and Bernini was soon travelling home with ample compensation in his pockets for his slighted talents.

1) e.g. The main carriage entrance was ridiculously insignificant. This was the design which Bernini would only allow Wren, then in Paris, to look at for a moment as a great privilege. He gave out that it was the result of divine inspiration. See illustrations in Blondel’s Architecture Française.

Meanwhile an intrigue had secured the royal sanction to a design by Claude Perrault, 1) a physician who had made a hobby of architecture. This with certain modifications was carried out by Le Veau, and thus arose the famous colonnade of the Louvre (10, 10). Being higher and longer than the older buildings, this scheme entailed the substitution of a third order for the attic on the E. and parts of the N. and S. sides of the court and the addition of a new river façade in front of that recently finished by Le Veau (11 etc.). This, together with the greater part of the N. outer front (9 etc.) was designed by Perrault (1667-74).

1) B. 1613, d. 1688. His brother Charles, who was employed in Colbert’s office, had engineered the intrigue.

The works were left unfinished and unroofed till in the reign of Louis XV Gabriel 1) (1755) and Soufflot 2) (1757), and in that of Louis XVI Brébion 3) carried out works of restoration and completion, to which Percier 4) and Fontaine 5) put the finishing touches under Napoleon I (1803). At this period the third order on the N. and S. sides of the court was carried on as far as the W. end, the attic being retained on the W. side only. The only further modification of importance undergone by the old Louvre was the refacing of its western outer front (6 etc.), (1853-7), to bring it into harmony with the new Louvre then in course of erection.

1) Jacques Ange Gabriel, b. 1698, d. 1782.

2) Jacques Germain Soufflot, b. 1709, d. 1780.

3) Maximilien Brébion, b. 1716, d. 1796.

4) Charles Percier, b. 1764, d. 1838.

5) Pierre François Fontaine, b. 1762, d. 1853.

II. THE TUILERIES PROPER.

A suburban site near the walls, named after tile and pottery works which had previously occupied it, was acquired in January, 1564, by Catharine de’ Medici for a more spacious residence than was possible within the confined limits of the Louvre, and free from the tragic associations of the Tournelles, where her husband had been killed in a tournament five years before.

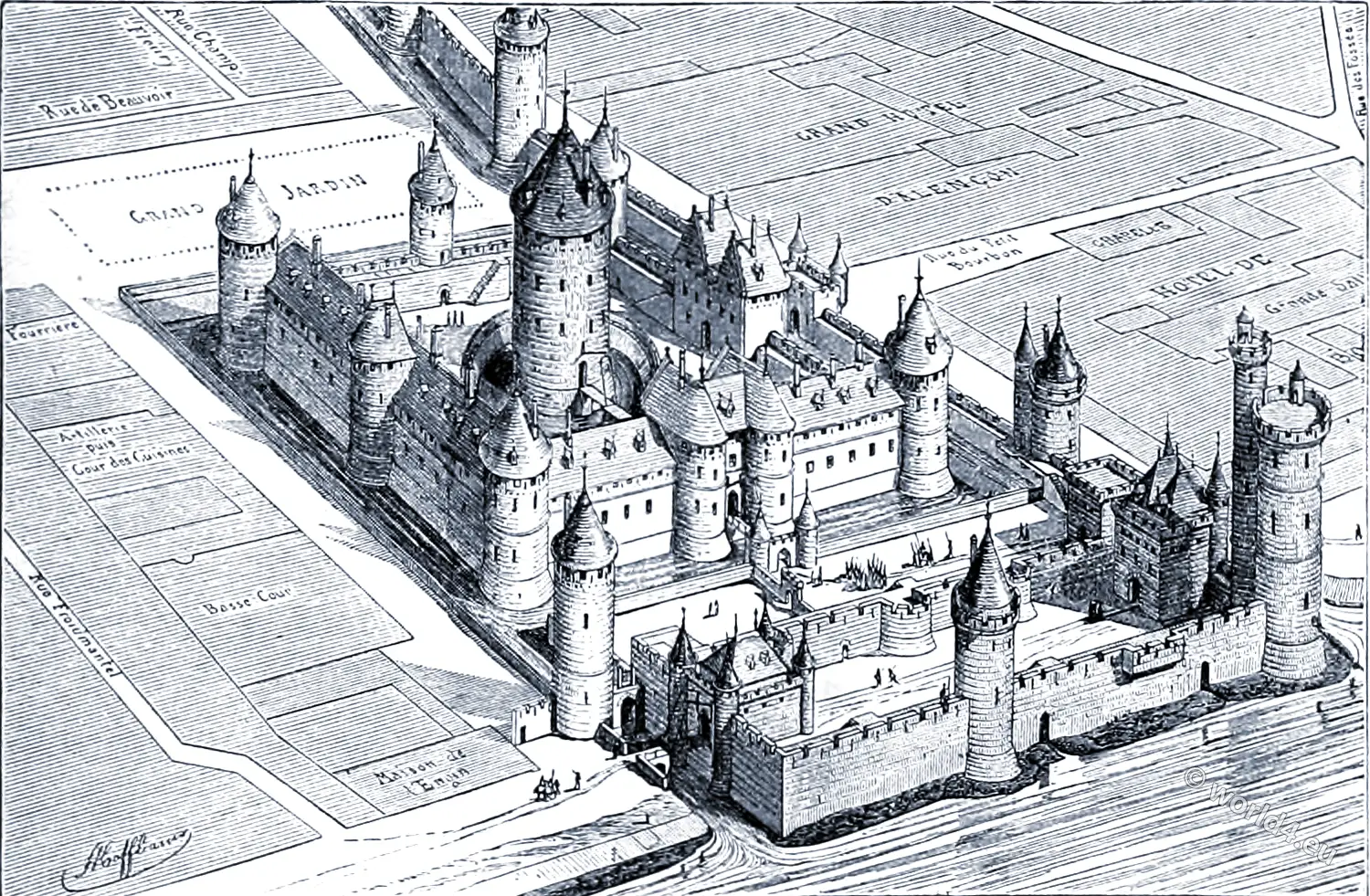

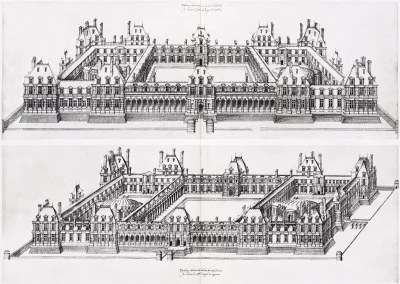

She entrusted the work to Philibert de l’Orme, *) who had been out of favour since that event. He prepared a scheme compared with which the Louvre would have been insignificant, but a very small portion of it was executed.

*) Philibert de l’Orme, b. c. 1512, d. 1570.

The plan measured about 875 feet by 540 feet. The south end was to face the river, the east front would have almost reached the walls and encroached on the moat, while the west front — the only part begun — looked on to a garden, laid out at the same time, in which Palissy *) erected a grotto of his enamelled earthenware.

*) Bernard Palissy, b. c. 1510, d. 1590.

At de l’Orme’s death (Jan., 1570) only the lower storey of the central pavilion (24a), containing a spiral stair of ingenious construction and the galleries on each side of it (24, 24), consisting of one storey preceded by a portico and surmounted by an elaborate attic, were complete. Hitherto these have been the only portions of the scheme of which the original elevation was known (cf. pi. 20).

Du Cerceau’s two bird’s-eye views (pl. 18, 19) show us with great fulness the entire design. From them we learn amongst other things that de l’Orme’s stair pavilion was not to terminate in an elliptical dome flanked by four cupolas, as is usually stated, *) but in the usual hipped roof—that the elliptical enclosures in the lateral courts shown on the plan were domed halls, probably intended for spectacular displays or dancing, and that the buildings round the lateral courts differed from the central portion in being both higher and plainer in treatment.

*) This treatment appears to have been due to one of HenryIV’s architects, possibly J. A. du Cerceau the younger.

Bullant 1) succeeded de l’Orme, but two years later (1572) the Queen Mother, frightened by the prediction of a soothsayer and finding the position too insecure in such troublous times, abandoned the building and commissioned him to design her a mansion within the walls. 2) His work at the Tuileries consisted in the addition of a pavilion at the south end (25) a sundial on its southern face, and possibly the first few courses of a corresponding pavilion on the north (23). He maintained the general lines of de l’Orme’s treatment, but omitted the bands on the columns, introduced broken and reversed pediments over the niches, and added an attic even more fantastic than that of the galleries.

1) Jean Bullant, b. c. 1525 (?) d. 1578.

2) The Hôtel de la Reine, later known as Hotel de Soissons. The only portion of which now survives is the column attached to the Bourse du Travail.

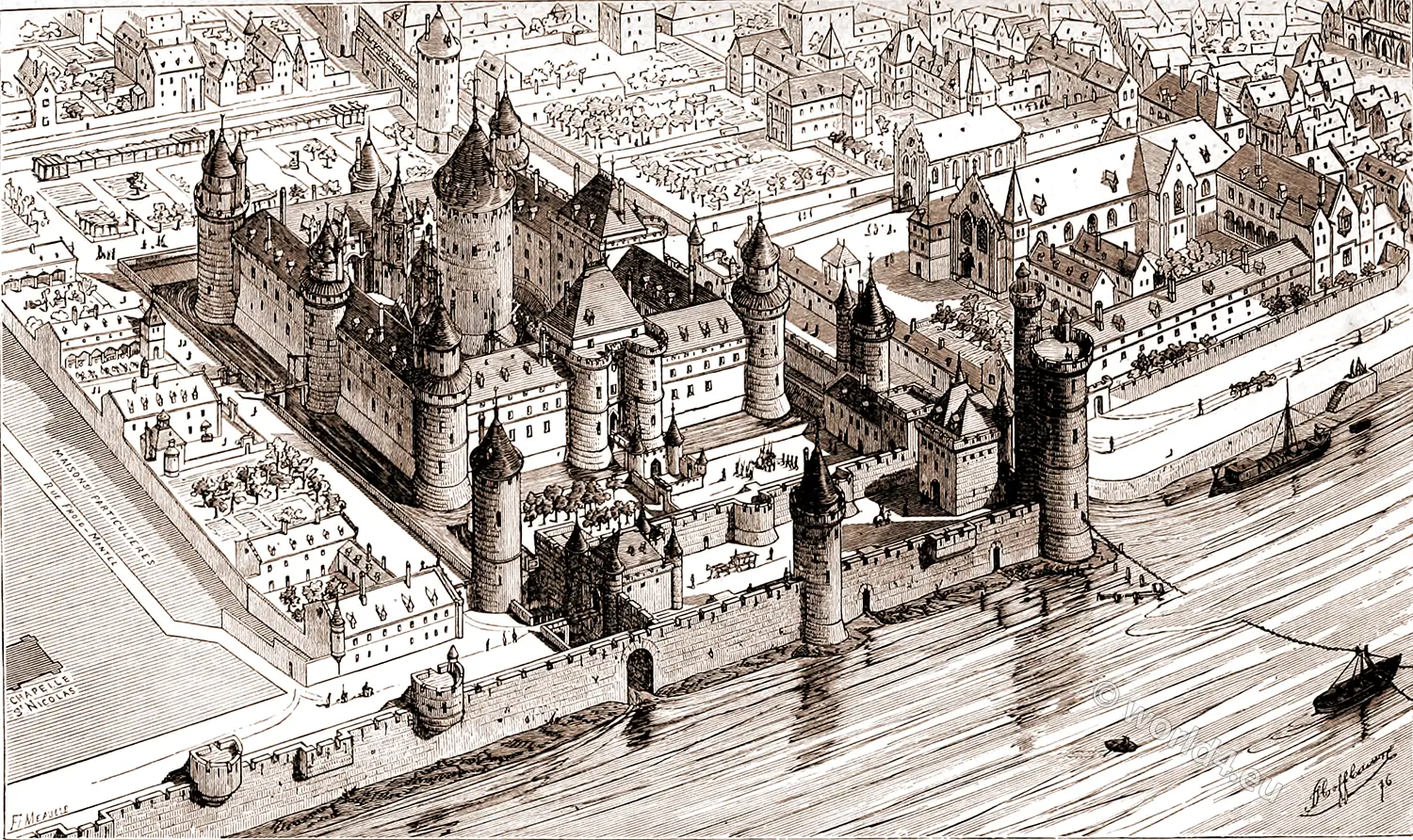

Nothing was done to the palace till Henry IV added the upper storey and dome to the stair pavilion (24a), and on the completion ofhis new waterside building (27, 28) connected the Pavilion de Flore (27) with Bullant’s pavilion by a block (26), forming the last link in the chain joining the two palaces (1609). This block, like the waterside buildings, was probably by J. A. du Cerceau the younger, and like them had a giant order embracing the two storeys, but a projecting stair-turret at each end had two orders and formed a transition from the old to the new treatment.

Though seventeenth century engravings balance the facade by repeating Bullant’s and du Cerceau’s blocks on the north side (21, 22, 23), there was in reality nothing built north of de l’Orme’s Gallery, nor was the completion taken in hand till the ministry of Colbert under Louis XIV, when the work was begun by Le Veau and continued by d’Orbay *) (1664-80).

*) Francois d’Orbay, son-in-law and pupil of Le Veau, b. 1634, d. 1697.

Their scheme involved a recasting of the existing buildings to bring them into comparative uniformity of height and treatment. For the central double pavilion (24a) a larger single one with an additional storey and square dome was substituted, the original staircase disappearing in the process. In de l’Orme’s galleries the attic was destroyed and a plain upper storey and attic added. In Bullant’s pavilion (25) the attic was also destroyed to make way for a plainer one.

In du Cerceau’s block (26) the stair turrets disappeared behind a new facade of similar treatment to the old but of more regular setting out. Both these blocks with their new Mansard roofs were repeated to the north (22, 23) and a uniform balustrade carried through from the central to the outermost pavilions, and the palace of Catharine thus enlarged was in this manner organically united to the northern and southern extensions.

The modifications since carried out at the Tuileries chiefly affected internal arrangements and neither they nor the buildings which grew upon the eastern side need be mentioned here. The palace was destroyed by a fire lit by the officers of the Commune on May 23rd and 24th, 1871 and its ruins removed in 1882.

III. THE JUNCTION OF THE PALACES.

Catharine de’ Medici seems at a nearly date to have had the idea of connecting the Louvre with her new palace by a series of galleries, but to Henry IV is due the first scheme for a more organic union by means of a vast court involving the removal of the intervening streets and fortifications. Neither this scheme nor those made for Louis XIV by Perrault 1) or Bernini 2) nor that made for Louis XV by Boffrand were put into execution.

1) Blondel’s Architecture Française, IV, pl. 1 and 2.

2) Blondel’s Architecture Française, IV, pl. 3.

Napoleon resumed the project and an instalment of a scheme prepared for him by Percier and Fontaine was actually built at each end of the N. side (5. 34). Napoleon III again took up the work, and, after the rejection of a scheme by Duban, 1) his architects, Visconti 2) and Lefuel, 3) finally carried it to a successful completion.

1) Jacques Felix Duban, b. 1797, d. 1870.

2) Louis Tullius Joachim Visconti, a naturalised Italian, b. 1791, d. 1853.

3) Hector Martin Lefuel, b. 1810, d. 18S0.

BUILDING OF THE SMALL GALLERY. General view, taken from the garden of the infanta. Costruction attributed to Pierre Chambiges, under Catherine de Mèdicis, and to Isaïe Fournier, under Henri IV, restored by Duban, under the presidency of Louis-Napoléon. BATIMENT DE LA PETITE GALERIE. Vue d’ensemble, prise du jardin de l’infante. Costruction attributée à Pierre Chambiges, sous Catherine de Mèdicis, et à Isaïe Fournier, sous Henri IV, restaurée par Duban, sous la présidence de Louis-Napoléon.

III (i). THE GREATER LOUVRE.

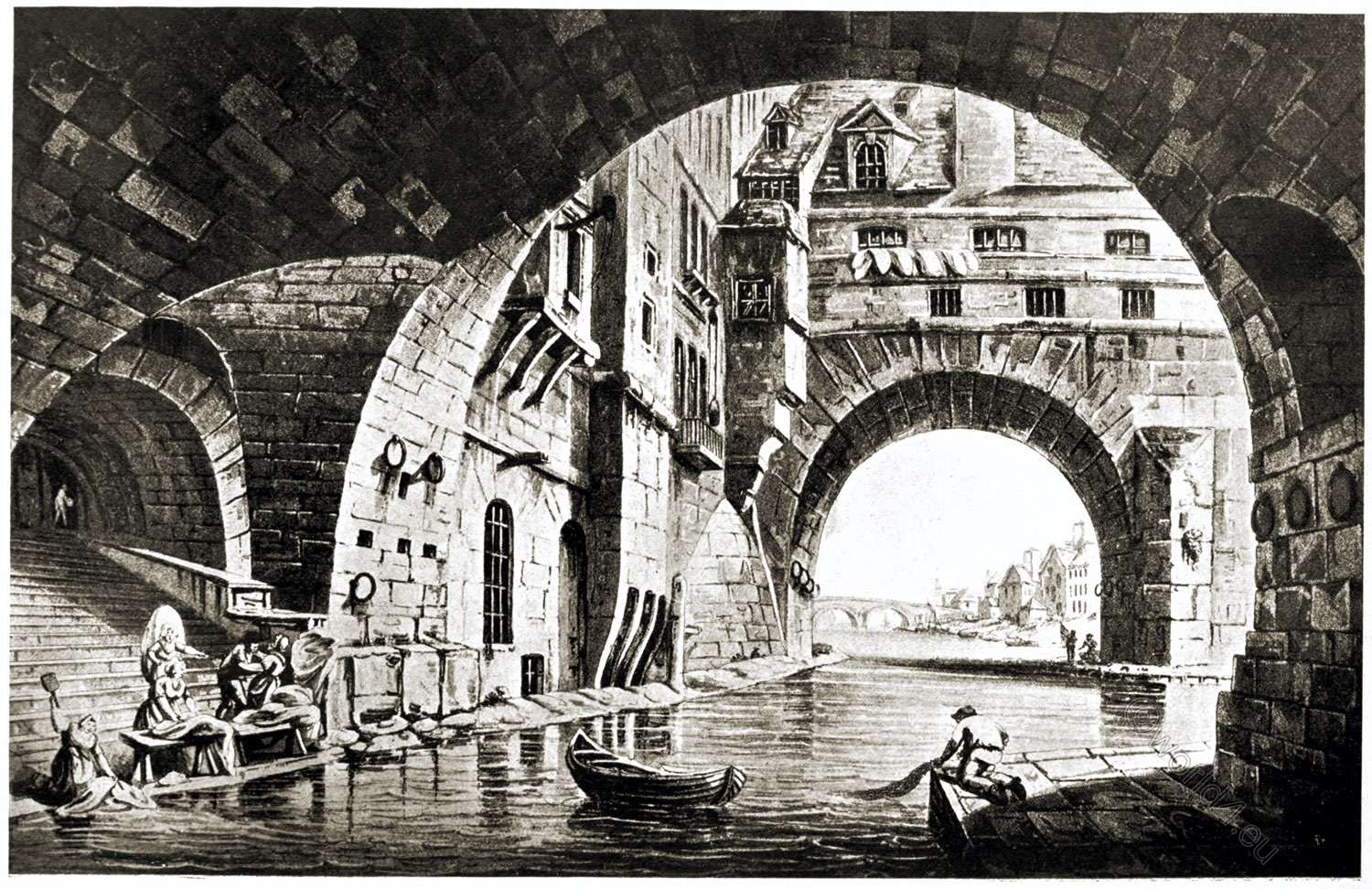

(0)The Southern Wing.—The earliest extension of the old Louvre outside the square court was made about 1566 by Catharine de’ Medici in the form of an open arcaded gallery over which was a balustraded terrace and which ran southwards from the S.W. angle of the palace (12). It was reached from the angle pavilion by a bridge-gallery (20) crossing the moat. Whether Pierre Chambiges the younger, to whom the design of the portico is usually attributed, was the architect or merely the contractoris doubtful; the bridge gallery may possibly have beende signed by the elder du Cerceau.

The object of this extension, later known as the Petite Galerie, was to permit the court to take the air and enjoy the prospect over the Seine without leaving the precincts of the palace.

The site of the Tuileries could also be reached from it by following the public walk along the riverside walls westward as far as the Porte Neuve (29), where they turned inland, and this may have suggested the idea of connecting the two palaces by a private and covered gallery.

The connection was not completed for forty years, but the first link in the chain was like the Petite Galerie begun by Catharine de Medici in the same or following year and like it consisted probably in a one-storeyed gallery with a terrace above it, *) showing great richness of treatment (14, 14).

*) The architect is unknown. He may have been Thibaut Métezeau of Dreux, b. 1533, d. 1596.

This so-called Grande Gallerie, extending westwards about as far as the Pavilion Lesdiguieres (15), seems to have been separated at first from the south end of the Petite Galerie by a budding known as the Maison de l’Engin, which was soon replaced by a new block (“Salle des Ambassadeurs,” “des Antiques,” or “d’Auguste”) of much plainer design (13).

Little work was done on any of these buildings after 1572 till Henry IV took them in hand (1594-9). His architect who may have been du Pérac 1) or one of the Métezeau family, 2) or each in succession, made the river front into a homogeneous composition.

1) Etienne du Perac, b. 1544, d. 1601.

2) Viz., Louis, b. 1557, d. 1615. Clement, b. 1581,d. 1652, was evidently too young to have been architect to this part of the palace. Both were sons of Thibant.

GRANDE GALLERY. Overall view. Construction under Catherine de Médicis and Henri IV, attributed to Thibaut and Louis Métezeau, Jacques Androuet du Cerceau and Étienne Dupérac; restoration by Duban, under the presidency of Louis-Napoléon. GRANDE GALERIE. Vue d’ensemble. Construction sous Catherine de Médicis et Henri IV, attributée a Thibaut et Louis Métezeau, Jacques Androuet du Cerceau et Étienne Dupérac; restauration de Duban, sous la présidence de Louis-Napoléon.

GRANDE GALERIE Detail of a section. Built under Catherine de Médicis and Henri IV, attributed to Thibaut and Louis Métezeau, Jacques Androuet du Cerceau and Étienne Dupérac; restored by Duban, under the presidency of Louis-Napoléon. GRANDE GALERIE Détail d’une travée. Construction sous Catherine de Médicis et Henri IV, attribuée à Thibaut et Louis Métezeau, Jacques Androuet du Cerceau et Étienne Dupérac; restauration de Duban, sous la présidence de Louis-Napoléon.

In the centre was a slightly projecting feature (now known by the misleading name “Porte Jean Goujon”) (14a), and at the west end buildings were designed to match the Salle des Antiques and the south front of the Petite Galerie at the east. *)

The Grande Galerie had been built at a lower level than the Petite, a fact which suggested the introduction of a mezzanine above its lower order so as to permit the upper storeys then added to the whole range of buildings and their orders to be on one level. Three narrow openings in the Grande Galerie gave access from the town to the river.

*) This pavilion, now called Pavilion de Lesdiguières, was crowned by a lantern, and was known as the “Lanterne des Galeries.”

Henry IV and Louis XIII further added some buildings to the north and west of the Petite Galerie, masking its junction with the old Louvre and the Grande Galerie and forming a small court known as “Cour de la Reine *) (D), and Anne of Austria transformed the Petite Galerie itself, which had hitherto been open, into apartments.

*) The present “Cour du Sphinx.”

NEW LOUVRE. General view of the Cour Lefuel (former Cour Caulaincourt). Built by H.-M. Lefuel during the reign of Napoleon III. NOUVEAU LOUVRE. Vue d’ensemble de la cour Lefuel (ancienne cour Caulaincourt). Construction de H.-M. Lefuel, sous le règne de Napoléon III.

New Louvre, North Wing. Overall view of the face on the Cour du Carrousel. Built by H.-M. Lefuel, under Napoleon. Nouveau Louvre, Aile Nord. Vue d’ensemble de la face sur la cour du Carrousel. Construction de H.-M. Lefuel, sous Napoléon III.

No further alteration of importance was made to the south wing of the Louvre till its restoration by Duban (1849-53), followed by Napoleon III’s comprehensive scheme for the junction of the two palaces, which involved the refacing of its northern facades and the erection of the buildings enclosing the courts (F, E, D) named after Visconti, Lefuel, and the Sphinx (1852-7), and comprising the Pavilions Mollien, Denon, Daru (17, 18, 19).

(b) The North Wing.— No attempt was made before the time of NapoleonI to join the two palaces on the north. Under him Percier and Fontaine began a wing running west from the N. W. angle of the old Louvre (5) and containing a rotunda to balance one included in the buildings of Henry IV and Louis XIII on the south (1811), and Fontaine alone built the Pavilion de Rohan (1) adjoining the new northern extension of the Tuileries (34) (1813-16). Finally, Visconti (1850-3) and Lefuel (1853-7) erected the ranges of buildings with their three small courts (A, B, B) and the Pavilions Turgot, Richelieu, and Colbert (2, 3, 4), which form the Ministry of Finance; Lefuel also refaced the work of Percier and Fontaine.

III (ii). THE GREATER TUILERIES.

(a)The South Wing. — Having finished the galleries of the Louvre, HenryIV added a southern wing to the Tuileries and thus completed the junction of the palaces. It did not stand quite on the site contemplated in de l’Orme’s plan, but a little further south, and, being in a line with the earlier riverside galleries, was out of square with the main front of the Tuileries (see fig. 14).

The main cornice of the Grande Galerie was continued, but a giant order on a high basement substituted for the two orders and intervening mezzanine. 1) The new gallery (28, 28) consisted of 14 bays with pediments alternately pointed and curved. 2) The same order was carried, at the western extremity, round the Pavilion de Flore (27), which had an additional storey and attic, 3) and along the block (26) which connected it with Bullant’s pavilion (25). All these buildings were erected between 1600 and 1609, and Jacques Androuet du Cerceau the younger was probably their architect, though the Pavilion de Flore is sometimes attributed to du Pérac.

- 1) The original treatment of this gallery was reproduced by Percier and Fontaine in their northern extension of the Tuileries, where part of it still exists (34).

- 2) Illustrated in Blondel’s Architecture Française, IV, pi. 24, 25, and 26.

- 3)Made in 1759, a little west of the Pavilion de Lesdiguières.

Little of importance was done to this part of the palace till after the completion of the new Louvre, when Lefuel, under the pretext of a restoration, not only rebuilt the Pavilion de Flore in a florid style of his own but refaced the river front of the gallery to imitate the Grande Galerie of the Louvre, adding a central feature (28a) to match the Porte Jean Goujon (14a) (1860-5).

At the same time here modelled the carriage way *) into the present Guichet des Sts. Péres (16), building the Pavilion de la Trémoille (30) to the west of it to match the Pavilion de Lesdiguieres (15), and rebuilt the north front to match the new Louvre with a projecting block containing the Salle des Etats (31).

The whole wing was damaged by the fire of 1871 and restored by Lefuel, and the demolition of the old Tuileries taking place at that time, the Pavilion de Flore was completed on the north.

*) Made in 1759, a little west of the Pavilion de Lesdiguières.

(b) The North Wing.—The only portion of the north wing of the Tuileries (which like the south wing is outside the limits of de l’Orme’s plan) erected before the nineteenth century was the Pavilion de Marsan (21), which formed part of Le Veau’s and d’Orbay’s scheme (1664-7), and was a replica of the original Pavilion de Flore. Under Napoleon I, a gallery running eastward from it was added by Percier and Fontaine (34), who copied the riverside gallery opposite, and also built the Arc du Carrousel (32). The pavilion (21) and part of this wing were damaged by the fire of 1871 and rebuilt by Lefuel (1873-8), the former to match his new Pavilion de Flore, and the latter (33) in a style inspired by the Grande Galerie of the Louvre.

Source:

- French châteaux and gardens in the XVIth century; a series of reproductions of contemporary drawings hitherto unpublished by William Henry Ward (1865-1924). London; B. T. Batsford; New York, C. Scribner & sons; 1909.

- Histoire du Louvre: Le château, le palais, le musée, des origines à nos jours, 1200-1928 by Louis Hautecoeur.

- L’architecture et la décoration aux palais du Louvre & des Tuileries. Paris, Librairie centrale d’art et d’architecture.

- Le Louvre et son histoire. Ouvrage illustré de 140 gravures sur bois et photogravures daprès des dessins, des plans et des estampes de l époque by Albert Babeau (1835-1913). Paris, Firmin-Didot, 1895.

- Sciences & lettres au moyen âge et à l’époque de la Renaissance, ouvrage illustré de treize chromolithographies par Jacob, P. L.. Paris, Firmin-Didot et cie, 1877.

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.