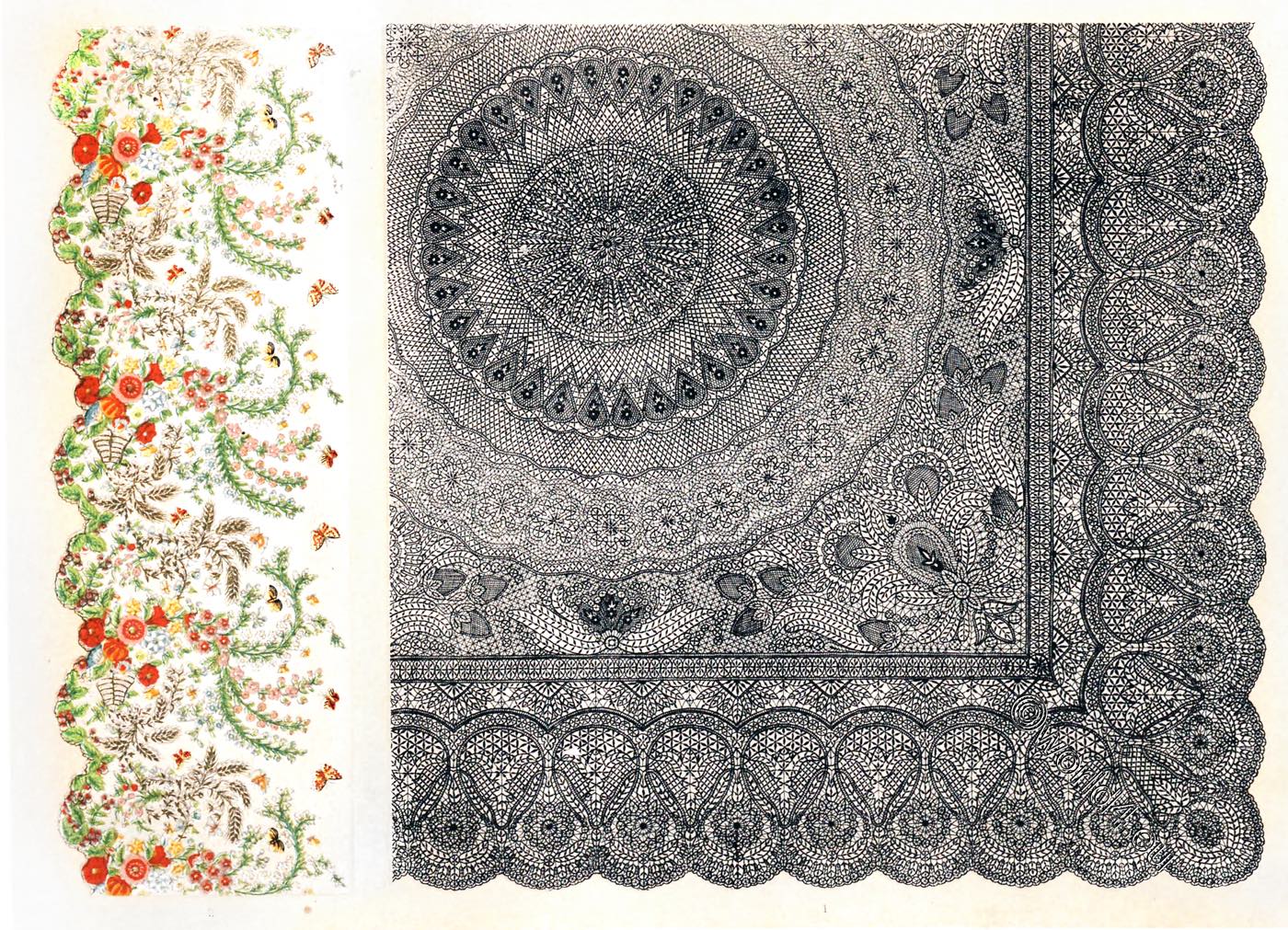

SPECIMENS OF TURKISH EMBROIDERY.

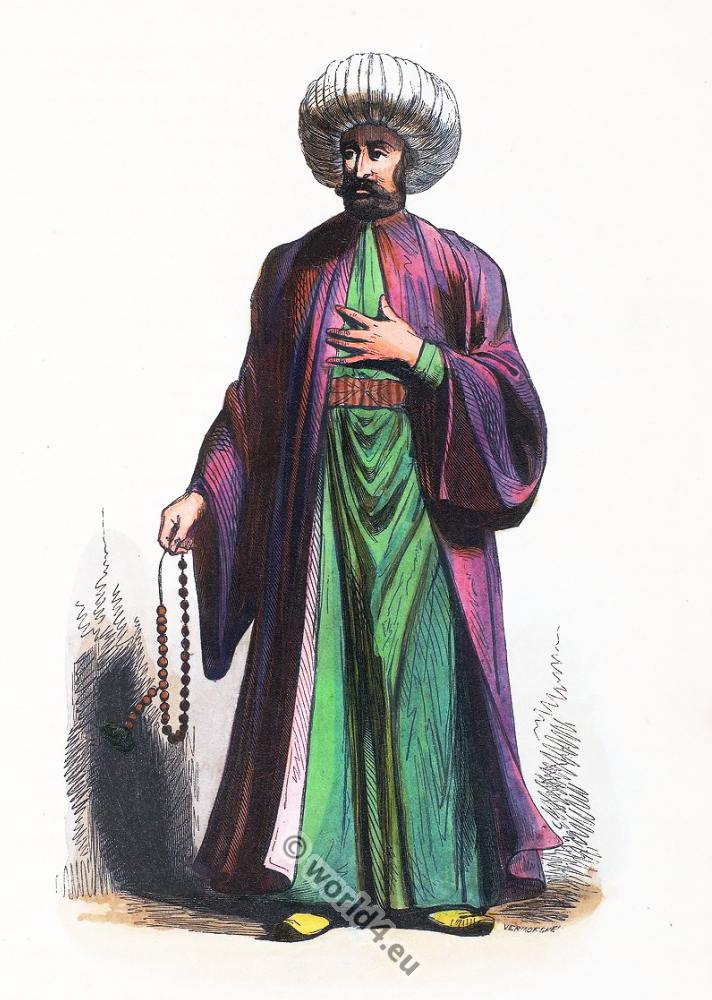

Although the Turks have hitherto manifested no distinctive peculiarity of excellence, either in the design or manufacture of common fabrics,— allowing themselves to he supplied with such articles by the more active and energetic countries of Europe,—they nevertheless display a decided predilection for the results ot indigenous labour, in those articles which are adapted for the use of the more wealthy and luxurious among their population. While common cotton goods and coarse muslins are supplied from England and Switzerland, and cotton prints, shawls, and needlework of an ordinary description, from France, the natives of Turkey, in which country so much of the excellence of ancient Moorish art still remains, devote great labour and ingenuity to the production of gorgeous silk stuffs and luxurious embroideries. The same amount of perfection manifested in those exquisite dyes and processes of dressing which have made the Turkey morocco leather, and the red cottons of Adrianople (Edirne), celebrated throughout Europe, is bestowed also upon the embellishment of the more elaborate articles of national costume.

The cotton of Turkey is not in any respect equal to that of India; and whether it be owing to the imperfect apparatus or labour employed in cleaning it, or to some inherent defect in its nature, certain it is that the finer fabrics, which serve, in Turkey, as a groundwork for the richest decorations of the needle, are for the most part produced by the looms of Persia and India. The muslin girdles and turbans, as well as the veils of the women, and those scarfs known as macramas, with which the Greek ladies are wont to cover the upper portion of the bosom when they have occasion to make visits, are almost entirely formed of fabrics the production of the last-named continent. The principal depot for these is at Smyrna, and at Constantinople they find a market amounting, together with that of other Indian cottons, to scarcely less than from eight to ten millions of piastres annually.

The silk goods of Turkey, which, as well as muslins, furnish the groundwork for costly embroideries, are principally produced in the neighborhood of Brousa (Bursa), in Asia Minor; a city which of late years has acquired considerable importance as the chief depot for the raw silk produced in the Turkish dominions. Very little embroidery is actually executed at Brousa; the silk which is forwarded from that city to Constantinople being generally consigned in the form either of twist or manufactured into plain fabrics.

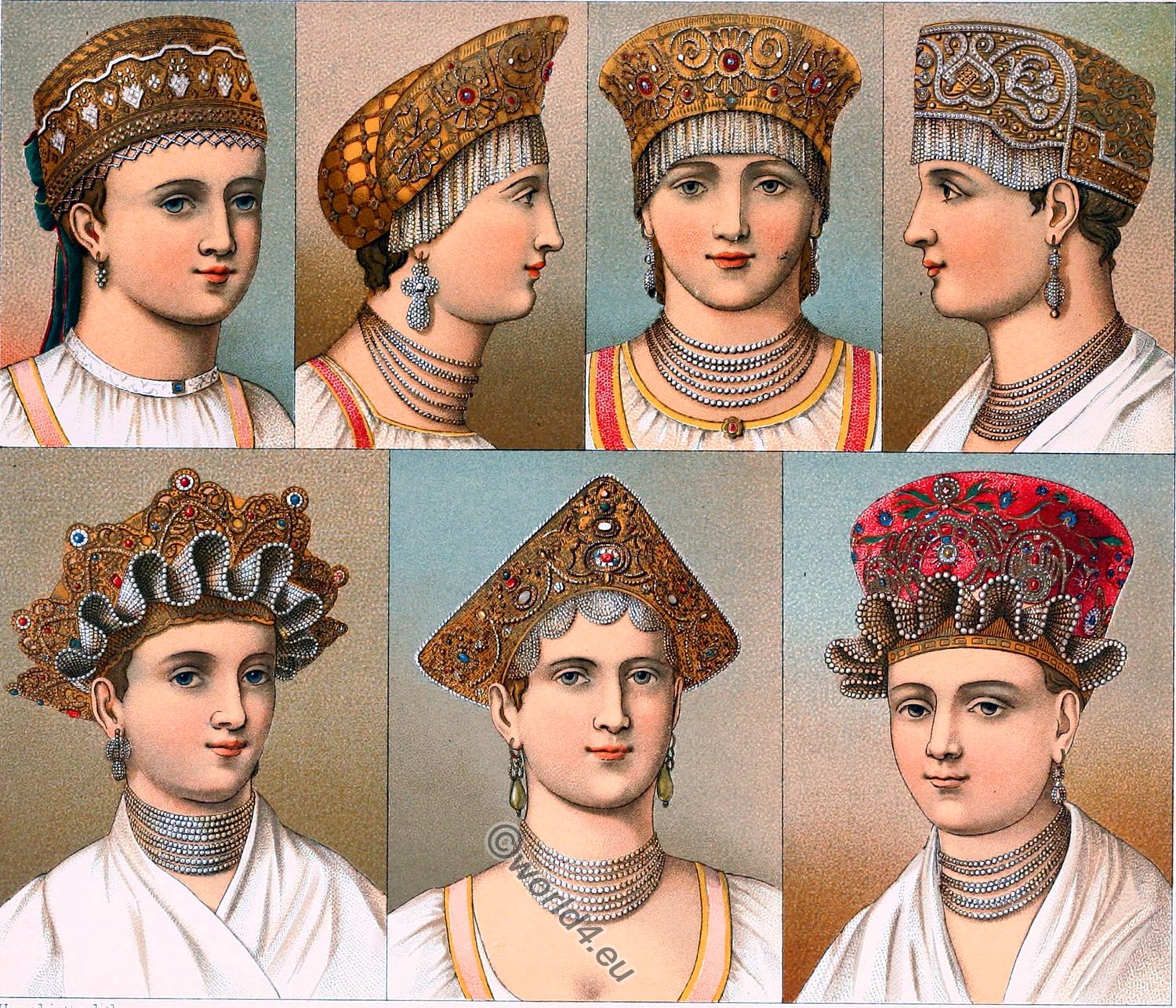

At Constantinople silks as well as muslins are provided by the merchants to the principal harems throughout the city. The females, whose lives would otherwise be inconceivably monotonous, devote many hours daily to the decoration of the superb costume of the wealthier inhabitants.

Thus it is we find that many of the articles in which feminine taste and skill are conspicuously displayed, bear tickets indicating that they are the productions either of the wives, daughters, or widows, of inhabitants of the metropolis. The beautiful manner in which it has been found possible, in a material so exquisitely delicate as the finest muslin, to draw home the threads which form the embroidered pattern, without distorting the regularity of the fabric, is truly remarkable. The elegance of the patterns, and the richness and harmony of the colours in which they are worked, convey a highly favorable idea of the national taste of the population.

Whilst in Indian, in Greek, and in Russian embroidery, the forms partake of a highly geometrical character, it is a peculiar feature in Turkish designs that they incline rather to that style of pattern which in England is called trailing; that is, one in which the shoots and irregular springings of nature are imitated, with but little modification.

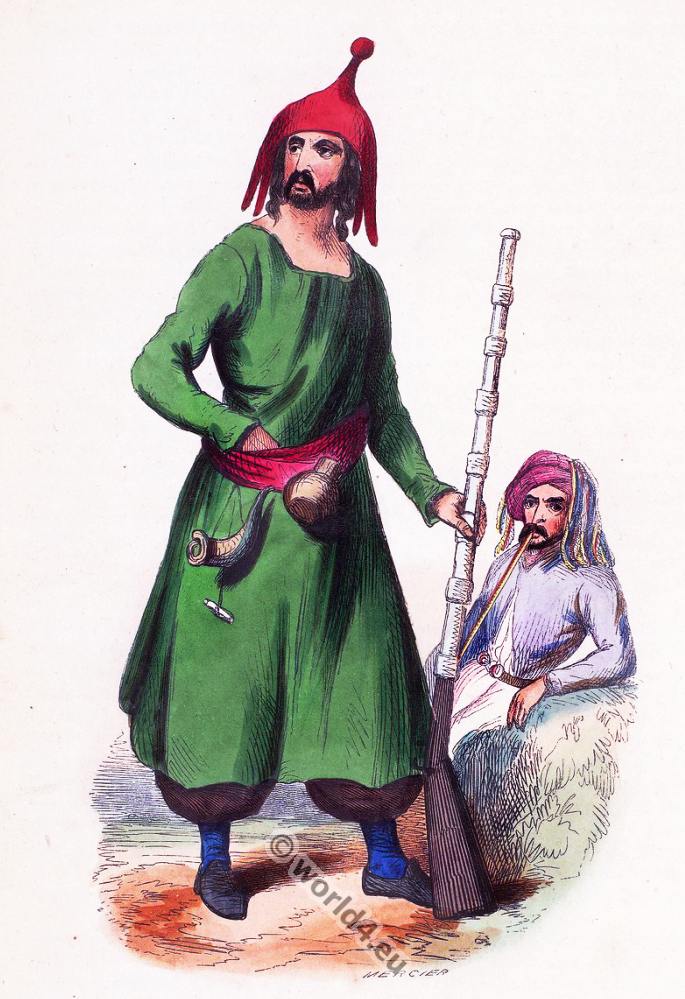

The goods which are thus produced by the labour of the females of Constantinople find a very considerable market at the celebrated fair of Balukhissar, a town situated about eighty-five miles northeast of Smyrna. This fair, which is one of the most considerable in the East, commences on the fifteenth of August, and lasts fourteen days. Long trains of camels and mules arrive from all parts of Asia, and more than 25,000 individuals are concentrated in the town and its environs. The bazaars are divided into sections, in which the nations not only of the East, but of Europe, find active commercial representatives. It is estimated that business amounting to twenty millions of piastres is annually transacted at this fair.

Some of the richest embroidered muslins in Turkey are manufactured for turbans—which are then called abame — and also for the handkerchiefs in which the ladies envelope their rich tresses after they have been disarranged in the bath, and previous to their receiving their usual elaborate plaiting and dressing.

The two central specimens engraved in the accompanying plate are executed on fine muslin: the top and bottom patterns exhibit the labour frequently lavished upon the enrichment of a material scarcely more delicate than the ordinary towelling of this country.

Source: The industrial arts of the nineteenth century. A series of illustrations of the choicest specimens produced by every nation, at the Great Exhibition of Works of Industry, by Sir Matthew Digby Wyatt and Eliza Paul Kirkbride Gurney. London: Day and Son 1851.

Continuing

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.