Indian Elephant Trapping.

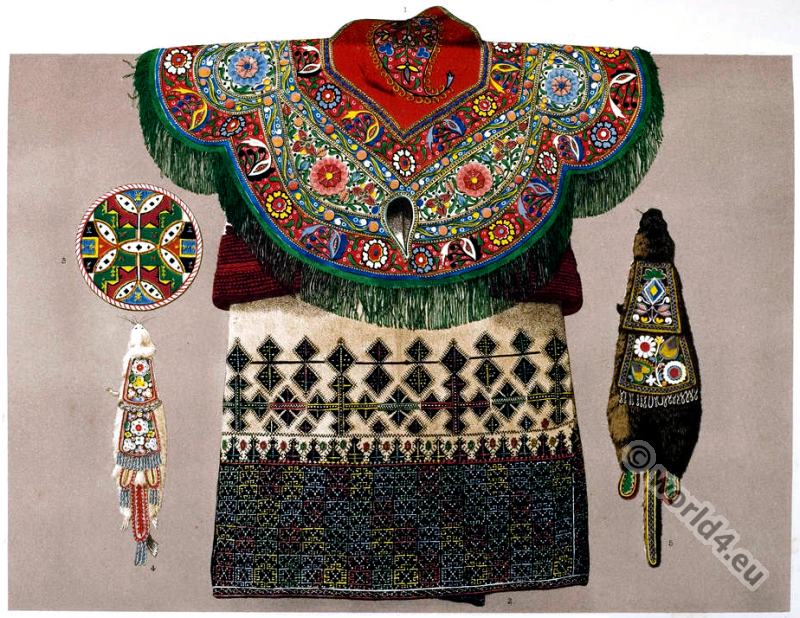

THE gorgeous specimen of embroidery which forms the subject of this plate, conveys some faint idea of the florid style of ornament which decorates the beautiful offerings made by His Highness the Nawab Nazim of Murshidabad to her Majesty the Queen of England. It forms part of a splendid velvet covering, worked with gold and silver, descending from the lower part of the howdah, or small pavilion, which, borne upon the back of an elephant, serves to shelter its rider from the intense rays of a tropical sun.

A magnificent howdah of this description, carved in ivory, and completely fitted up for use, with all its accessories, together with a complete suit of elephant trapping, forms the principal portion of the present to which we have alluded. To this truly regal gift the Nawab has added a superb throne, or native reception seat, with its canopy, and a frame-work of silver, serving to support the pillows. Two mookals (emblems of rank), and two palanquins, one richly fitted up for state occasions, and the other without a canopy, complete the present. The style and character of these elaborate objects admirably illustrate the Oriental splendor with which the native princes make their visits of pomp, and their progresses of parade.

The state trappings of an elephant consist of a large cloth, which completely covers the body of the animal, and falls down to within a short distance of his feet. In the present instance this covering is of velvet, embroidered all over, in a style similar to that exhibited in the accompanying plate. Upon this cloth the howdah, or pavilion, is placed, the frame-work of which serves to support a canopy, beneath which the prince or noble takes his seat. Behind rises a distinct and less lofty canopy, which is occupied by an attendant, whose duty it is, with a plume of feathers, to whisk away the insects which buzz around, and, but for his interference, would much annoy his lord.

The dexterity with which this duty is performed, is a theme of admiration to all who have witnessed it. In front of the howdah, astride upon the neck of the elephant, and furnished with a goad, by means of which he directs the movements of the animal, sits the driver. Over his head is stretched an awning, supported by two rods projecting from the lower part of the howdah. In front of the driver, and covering the head of the elephant, is spread another piece of cloth, embroidered even more richly than the rest of the trappings. On each side of the animal’s ears, and almost concealing them, hang long cords of gold and silver twist.

From each side of the howdah depends a gorgeous piece of embroidery, partially covering the great cloth already mentioned, and from one angle of this smaller or uppermost cloth our illustration is taken, serving but imperfectly to represent the extreme brilliancy of the original, the gold of which is highly burnished and of the greatest purity. The beauty of the patterns worked in bullion which enrich the velvet, and the woven silk, or kincob, which forms the covering of the howdah, is most remarkable; and, when lit up by the intense rays of an Eastern sun, we can imagine the whole panoply to present a gorgeous appearance, investing the movements of the unwieldy animal with as near an approximation to grace and dignity as its clumsy action will permit.

From the earliest periods, the elephants of India have been peculiarly identified with regal magnificence. When Alexander the Great first came in contact with them, and perceived their splendor in state and their utility in war, he determined upon introducing them into Greece. The experiment, however, proved unsuccessful, since the expense and difficulty of maintaining them offered an insuperable obstacle to his project. Introduced at a subsequent period into Italy, by the armies of Pyrrhus, however imposing their appearance, they proved an unequal match for the ingenuity of Hannibal and the valour of the Roman soldiers.

Degraded from their dignified and warlike position, they sunk into the occasional ornaments of imperial triumphs, and ultimately, in the reign of Nero, mounted the stage in the public games, under the yet more equivocal guise of rope-dancers. In the middle ages, a celebrated elephant was presented by the Soldan of Babylon to the Emperor Frederick the Second; and King Henry the Third had also an elephant, which was publicly exhibited

in England.*

The commercial intercourse which existed between India and Italy was not confined to the importation of elephants into the latter country; since Pliny tells us that, in his time, the Roman citizens devoted no less than fifty millions of sesterces annually (more than 400,000/.) in procuring for themselves the luxuries of the East. Among these we have reason to believe that silks and silk stuffs formed no inconsiderable item. It is not indeed impossible, that the splendid embroideries of India, thus made familiar in the West, contributed to that taste for elaborately decorated garments, which was transmitted to the rest of Europe from Byzantium; and may, even at the present moment, be exerting an influence over the productions of Muhlhausen and Manchester.

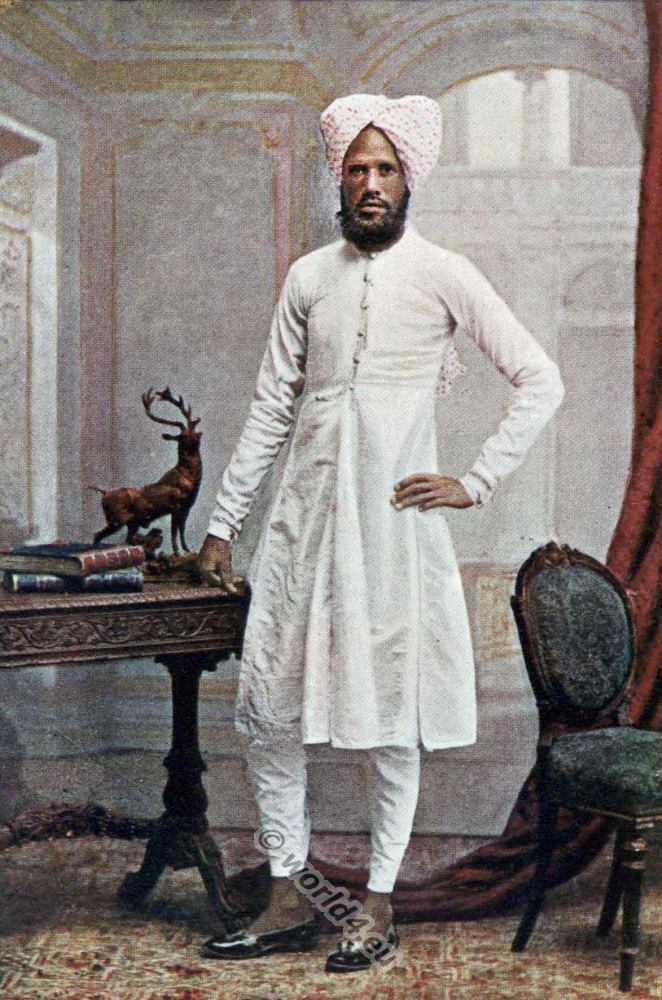

A peculiar interest attaches to any objects produced at Murshidabad, on three accounts. In the first place, since that city, and its adjacent Port of Cossimbazar (Kasim Bazar), are celebrated as the most important foci of the silk-trade in India; serving not only as the greatest depot for raw silk, but as the principal manufacturing centre, from whence many of the most distant countries of the Peninsula are supplied with twist and made-up goods. The Cossimbazar Corahs are, indeed, largely imported into this country: most of what are known as “real India silk” pocket-handkerchiefs emanating from that district.

In the second, because from 1704 to 1750, Murshidabad was the capital of Bengal; and may, therefore, be regarded as serving to illustrate the most important native industry of that celebrated province; and, in the third place, because when Murshidabad, in 1701, removed the seat of government from Dacca to his new metropolis, to which he gave his own name, he brought with him the most skilled artificers of Dacca, on the traditions of excellence descending from which all the art of that portion of the country appears to have been based.

Source: The industrial arts of the nineteenth century. A series of illustrations of the choicest specimens produced by every nation, at the Great Exhibition of Works of Industry by Eliza Paul Kirkbride Gurney, Matthew Digby Wyatt. London: Day and Son 1851.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.