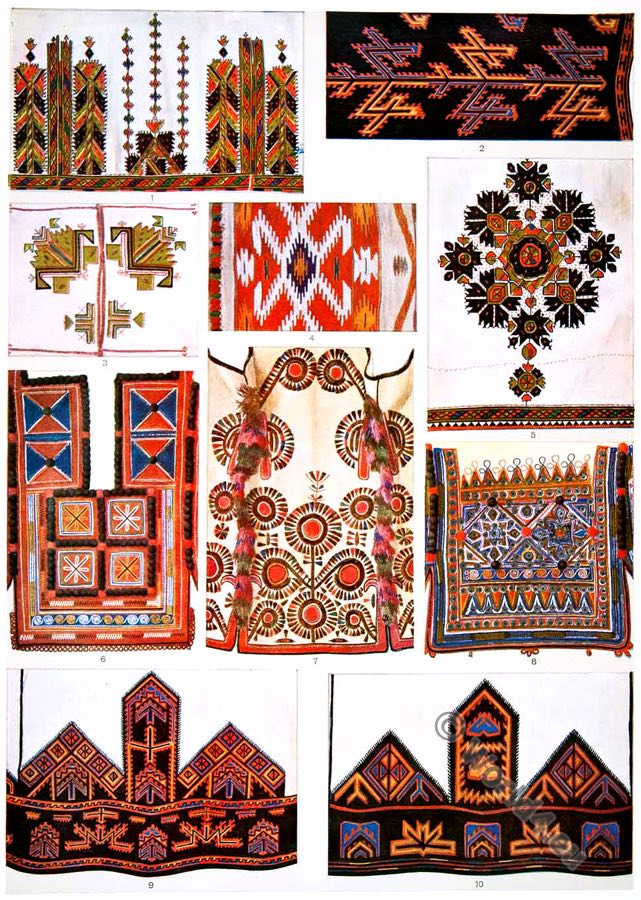

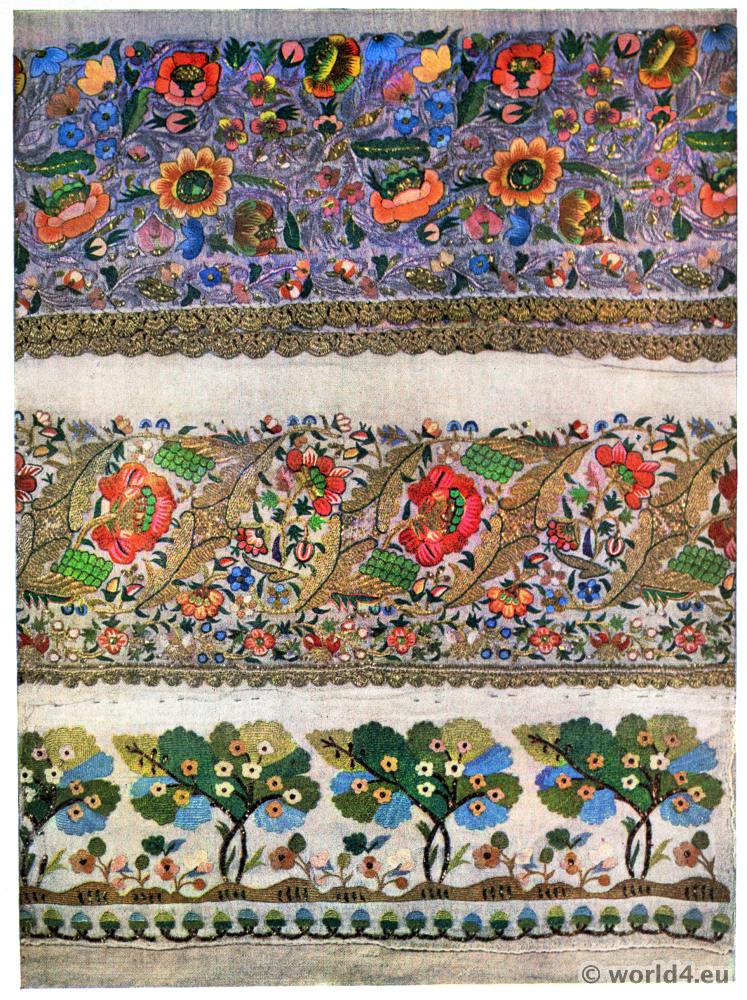

GREEK EMBROIDERY.

PLATE LXXVI.

Embroidery of a rich Fermeli.

The object we engrave forms a portion of a rich Fermeli, or upper jacket, which was included in a complete suit of elaborate Palikar costume, contributed to the Great Exhibition by one of the principal manufacturers of Greece.

We gather from the formation contained in the “Official Illustrated Catalogue,” that the art of embroidery, both m silk and gold, has of late been considerably improved in Greece. The silk-embroidered dresses are of an inferior description, whilst those executed in gold thread are only used by the higher classes. As respects men’s apparel, gold embroidery is only in use among the irregular troops of the army, and there only by the most wealthy.

The costume for ladies consists of a short mantelet, which, if embroidered in silk, costs about 60 drachmas 1) and if in gold from 100 to 400 drachmas, according to circumstances. The male costumes sent for exhibition, comprising the entire dress, varied in price from 2000 to 6000 drachmas. The finest of these were executed by workmen, who, from their taste having been cultivated in the School of Design established by King Otho 2), have been enabled to give a more than usually artistic character to the objects they have produced.

1) The Greek drachma is equal iu value to about 8d. English.

2) Otto Friedrich Ludwig of Wittelsbach (Greek Othon, 1815 – 1867) was a Bavarian prince and from 1832 until 1862 first king of Greece.

That splendour of dress, which, in the midst of great penury, the true-born Greek clings to as the indispensable mark by which his pretensions to gentility may be recognized, is proverbial. Many of the modern Greeks may thus be said, like the gallants of the Field of the Cloth of Gold, to carry their fortunes on their backs.

Where any great complexity of design is involved, or any peculiar richness of material employed, the work is executed by individual tailors, each trading on his own account and employing a few occasional journeymen only. I he system of maintaining a large establishment of workmen, or executing these labors in factories, does not yet appear to have been contemplated by the Greeks. Thus it is that every dress in which superior ornamentation is required has to be specifically ordered, and, excepting in the largest towns, it is extremely difficult to find any such garments ready made or kept in stock. It appears that the district of Janina, in Albania, is that most celebrated for the superiority of its embroidery, and the good taste of its designs; and many portions of Greece are supplied from thence.

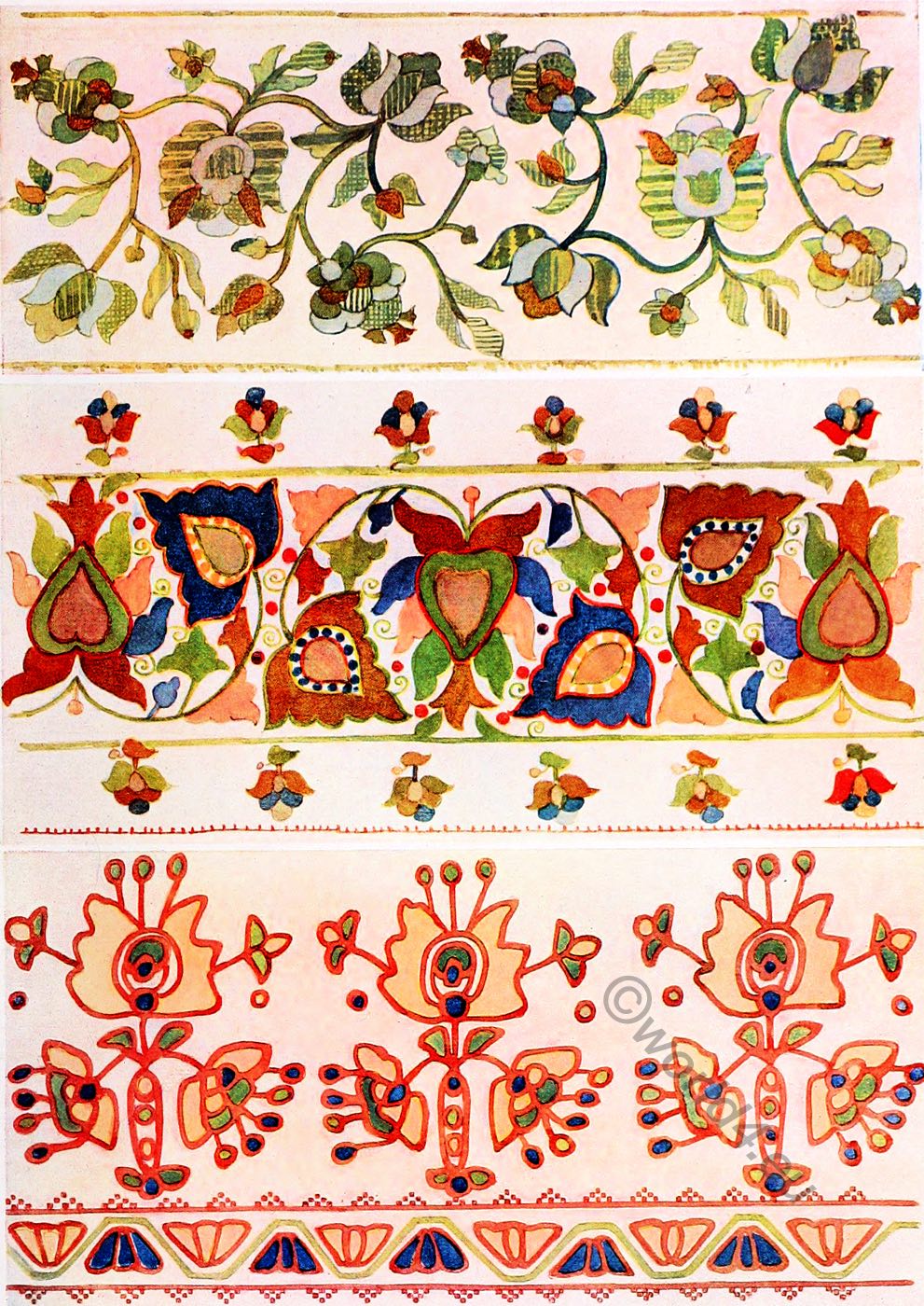

Next in celebrity to Janina, comes Athens; but between these and the smaller towns no very great difference can be said to exist: for so popular is this elaborate style of enrichment, and so universal the demand for gorgeously-decorated costume, especially on such occasions as marriages and other great festivals, that usually, even in the smallest towns, workmen may be found capable of understanding and executing a complicated and elaborate order. The character of the ornament varies but little throughout the country. It appears, however, that there are two traditional classes of design; one resembling the Turkish, and consisting generally of irregular scrolls with occasional quaint interfacings, and odd angular projections, and the other recalling that peculiar type of spiral-work which may be regarded as the Ionian characteristic of ancient Greek art. It is rare, however, to find either of these styles perfectly and consistently carried out; since while natural good taste induces an inclination for the ancient Greek style, the caprices of fashion, and the effect of the long subjection of the country to Ottoman rule, have caused the introduction of a mixture of Constantinopolitan taste. Hence has arisen a hybrid style, in which, however, the Turkish manner strongly predominates.

It is not to be imagined that the rich jackets and other garments, such as the doulamas, fustenellas, gaiters, &c., covered over with enrichments and complicated interlacing of gold or silver thread, can be by any means universally worn: their use must obviously be confined to the aristocracy; whilst more humble individuals wear a more homely variety of costume, in which, however, though the cloth is coarser and less costly, and though wool and thread take the place of gold and silver, still the general effect aimed at is much the same throughout all classes. From some information with which we have been obligingly favoured by Mr. R. P. Pullan, we find that the cost of a rich suit complete is about 35l., whilst a more common description of dress, although still very handsome, may be had for about 10l. 10s.

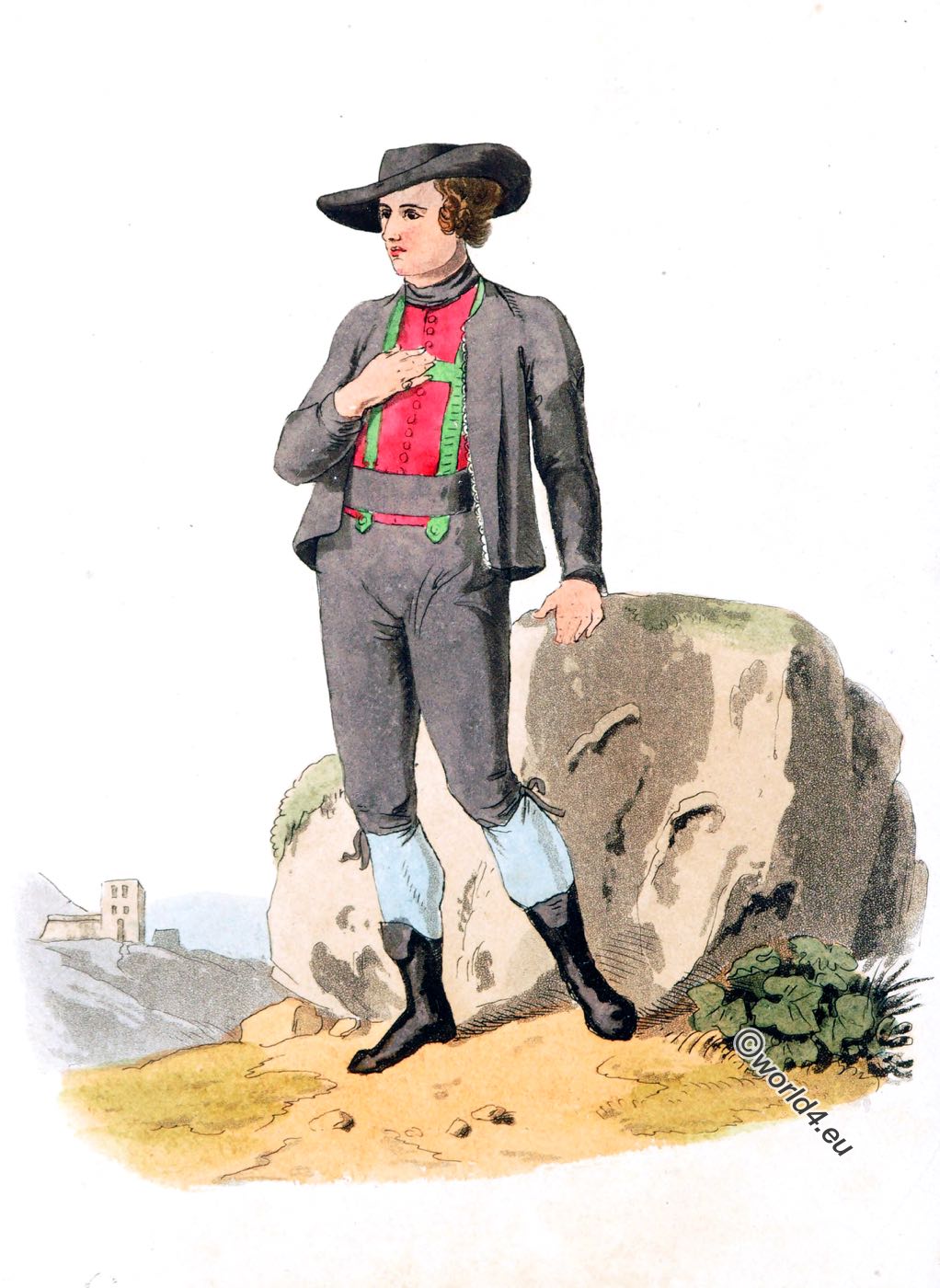

The style of costume of Albania, it is well known, is almost precisely similar to that of Greece. We gather from the interesting notes of Mr. Edward Lear *) that “of all the tribes of that country, that of the Ghegheria surpasses all its neighbors in gorgeousness of raiment, by adding to their other vestments a long surtout of purple, crimson, or scarlet, trimmed with fur, or bordered with gold thread or braiding. Their jackets and waistcoats are usually black.

The Albanian bridal attire is most splendid. Purple silk and velvet, elaborately embroidered in gold and silver, form the outer garment; the patterns worked by hand – with the greatest taste: two or three under-vests covered with embroidery; full purple trowsers; innumerable chains of gold and silver coins and medals; with, a long white and several colored silk handkerchiefs, complete a dress which is only worn on great fete days, or such great occasions as marriages and christenings.

While the most important part of the preparation of Greek costume is executed by men, much of the more laborious portion is executed by women. Certain patterns become traditional in families, but in many cases such is the skill of those employed that they will commence the execution of an elaborate piece of ornament with neither drawing nor any other sort of guide before them. Sketching in w ith the needle the general outline of the ornament with which they propose to fill up the space allotted for decoration, they proceed at once to apply the gold or silver thread. The principal parts of the costume on which decoration is lavished consist of the lower part of the sleeves, and the back of the upper jacket, the front of the vest which is worn beneath, and the lower part of the front of the fustenella, or garment, which in form resembles the kilt. The gaiters are always most splendidly ornamented. The cap usually worn is the fez, which is decorated only with a gold tassel; the most usual colors are scarlet and dark purple.

A considerable developement of the general manufactures of Greece has taken place of late years, and many materials essential to the making up of their ordinary costume, which were formerly obtained from Turkey, and even from Italy, are now produced in the country” itself. Thus the great silk factory, which was established by Sig. Lucas Ralli on the Piraeus at Athens, about six years ago, is now in full work, and produces annually a large quantity of silk; the greater portion of which is consumed in sashes and belts for the men, and rich garments for the women.

*) “Journals of a Landscape Painter in Albania, &c.”

Source: The industrial arts of the nineteenth century. A series of illustrations of the choicest specimens produced by every nation, at the Great Exhibition of Works of Industry by Eliza Paul Kirkbride Gurney, Matthew Digby Wyatt. London: Day and Son 1851.