ALBANIAN EMBROIDERY.

PLATE LXXX.

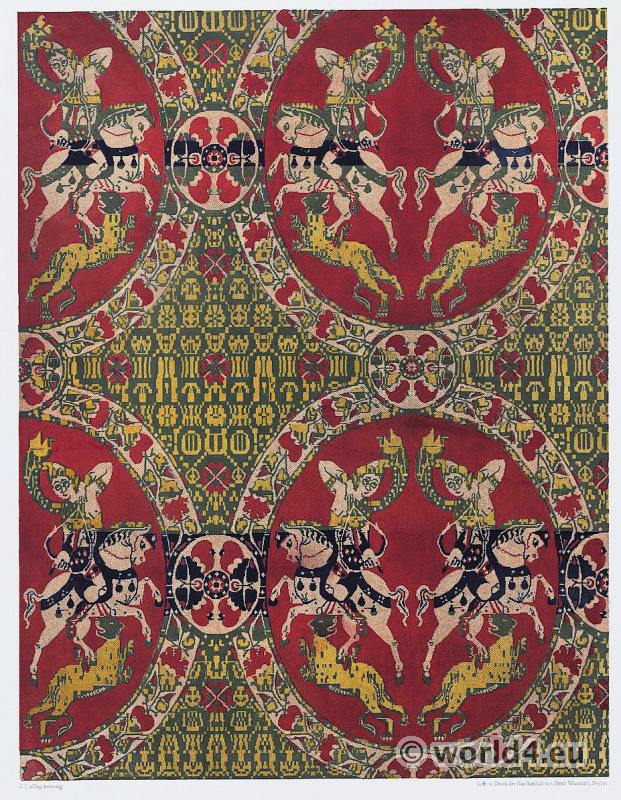

Byzantine dalmatica of the 12th century.

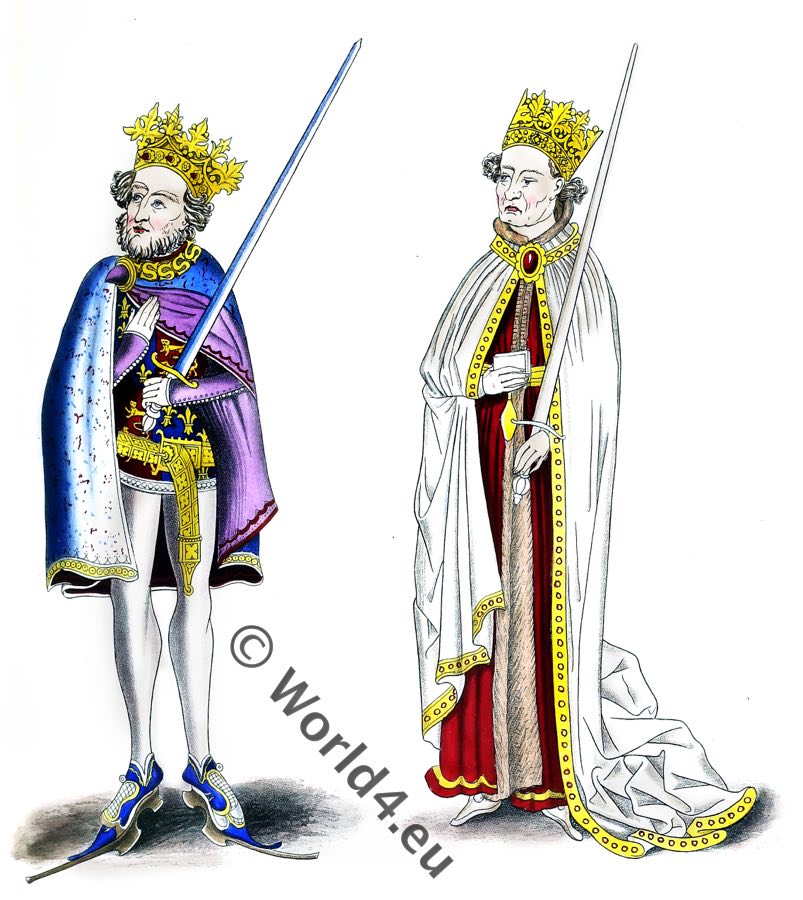

Having, in our notice of Plate LXXVL, examined the character of the modern costume of Greece and Albania, we shall, on the present occasion, advert to the history of costume-embroidery from the earliest foundation of the Greek Empire.

The love of magnificence and of elaborate, though semi-barbaric art, for which Constantine the Great was so remarkable, unquestionably afforded a powerful stimulus to the labors of those Roman artists whom he carried with him to his new capital, to supply his personal wants, as well as those of his newly-founded Church.

In the earliest diptychs we find *) indications of embroidery on portions of the garments represented in the consular portraits. The most ancient manuscripts and mosaics afford still clearer evidence as to the early-developed partiality of the Greeks for similar rich decorations.

Their intercourse with Persia and the East no doubt fostered this taste, since the inhabitants of those regions had long been famed for the magnificence of their costume, and the skill with which their precious cloths and hangings were executed in the loom and adorned by the needle.

It is reasonable, therefore, to find in the earliest representations of Greek embroidery a decidedly Oriental character; and in proportion as the power of the Saracenic races increased, so do we more and more clearly recognize the influence of the arts of design which they practiced reacting upon the Byzantines, from whom the first and leading elements of those arts had been derived.

- Vide Gorius, passim.

Ciampini *) displays great learning in tracing the retention, by the Greeks of the Lower Empire, of the practice of their classic ancestors of embroidering inscriptions on the hems of their garments. He cites especially a homily on the subject of the Rich Man and Lazarus, by St. Asterius, who exclaims against the custom of embroidering sacred and profane histories on vestments.

*) Giovanni Giustino Ciampini (1633-1698 was an Italian clergyman, historian and Christian archaeologist.) “Vetera Monimenta, musiva opera illustrantur. Pars prima.” Folio. Rome, 1690, p. 92.

Anastasius, in his life of Leo IV. (who became Pope a.d. 847), describes a veil which hung about his altar as woven with gold, and glittering all over with pearls; having, on the right and left hand, subjects enriched with gems, with little gold circlets round the whole, on which was inscribed the name of the donor.

A careful examination of several of the earliest Greek mosaics enabled Ciampini to collect, from the representations of similar embroideries which they furnish to the antiquary, a series of interesting monograms and inscriptions, which he has given in his work.

There can be no doubt that the Greeks long continued to execute such embroideries, which were generally adopted in Italy as orphreys and edgings for robes and vestments; for we find in the pictures of the later Greek masters, and of the early Siennese, Neapolitan, and Venetian schools, frequent representations of figures clad in plain and enriched stuffs, having almost invariably edgings worked in gold, and exhibiting sometimes Greek, sometimes Latin, and sometimes Cufic inscriptions, together with ornaments displaying a decided analogy with those forms which are of most frequent occurrence in Byzantine mosaics, enamels, and manuscripts.

In a previous article (Plate XX.) we quoted the observation of St. John Chrysostom, that in his time all admiration was reserved for the works of the goldsmith and the weaver. Of sumptuous robes of Greek workmanship the most precious, and indeed the only perfect, specimen known to be in existence, is the celebrated Cappa di San Leone.

The Dalmatica, as it is otherwise called, is preserved in the sacristy of St. Peter’s at Rome, and is covered with sacred subjects, embroidered in gold and silver: and although the style of the representations is dry and lifeless, it must be considered as a fair specimen of the technical execution of such work at the period of its fabrication, about the twelfth century.

Dr. Kugler *) considers it to be of undoubted Greek workmanship from Constantinople. It is very interesting, as showing the extreme richness of composition employed in such embroideries.

We are informed by the Rev. Mr. Hartshorne **) that “the work is laid upon a foundation of deep blue silk, having four different subjects on the shoulders, behind and in front, exhibiting, although taken from different actions, the glorification of the body of our Lord, the whole has been carefully wrought with gold tambour and silk; and the numerous figures as many as fifty-tom surrounding the Redeemer, who sits enthroned on a rainbow in the centre, display simplicity and gracefulness of design.

The field of the vestment is powdered with flowers and crosses of gold and silver, having the bottom enriched with a running floriated pattern. It has also a representation of Paradise, wherein the flowers, carried by tigers of gold, are of emerald green, turquoise blue, and flame color. Crosses of silver cantoned with tears of gold, and of gold cantoned with tears of silver alternately, are inserted in the flowing foliage at the edge.

Other crosses within circles are also placed after the same rule; when of gold, in medallions of silver; and when of silver, in the reverse order.”

“I do not apprehend” says Lord Lindsay, in his “History of Christian Art, “your being disappointed with the Dalmatica di San Leone, or your dissenting from my conclusion, that a master — a Michael Angelo, I would almost say — then flourished at Byzantium. It was in this Dalmatiea — then semée all over with pearls, and glittering in freshness — that Cola di Rienzi robed himself over his armor in the sacristy of St. Peter’s, and thence ascended to the palace of the Popes, after the manner of the Caesars, with sounding trumpets and his horsemen following him, — his truncheon in his hand, and his crown on his head,— ‘terribile e fantastice’ as his biographer describes him,—to wait upon the legate.”

The sacristy of the church of St. Apollinaris in Classe, in the exarchate of Ravenna, possesses some fragments of a very ancient embroidered chasuble, on the orphrey or border of which were figures of saints and bishops, with the names of each in small shields. The fabric of these interesting relics is of silver and silk,—a manufacture which is of later introduction for the material of church vestments than gold.

According to Salmusius, silver tissue was not made or used in churches till the times of the last Byzantine emperors. From this circumstance we may form some conclusion as to the date of this chasuble, which may be assumed as representing the last stage of Greek embroidery.

We shall hereafter take an opportunity of tracing the very important influence which, as we conceive, the great popularity of the style of workmanship, adopted in the costume of the Byzantine court, effected throughout nearly the whole extent of the habitable globe.

*)“Handbook of the History of Art.” **)”English Mediaeval Embroidery,” p. 62. Parker, London and Oxford.

Source: The industrial arts of the nineteenth century. A series of illustrations of the choicest specimens produced by every nation, at the Great Exhibition of Works of Industry, 1851 by Sir Matthew Digby Wyatt, (1820-1877); Eliza Paul Kirkbride Gurney (1801-1881). London: Day and Son. Great Exhibition 1851.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.