Virgil’s tomb (Italian: Tomba di Virgilio) is a Roman-era crypt in Naples, believed to be the grave of the poet Virgil (15 October 70 BC – 21 September 19 BC). It is located at the entrance of an ancient Roman tunnel called “grotta vecchia” or “cripta napoletana Piedigrotta”, situated in the district of Piedigrotta between Mergellina and Fuorigrotta. It is located at the top of the Virgilio Park.

Virgil’s tomb has been a place of pilgrimage for centuries, and even Petrarch and Boccaccio visited the shrine. It seems that the nearby church of Santa Maria di Piedigrotta was erected by the ecclesiastical authorities in order to put an end to this pagan worship and to “Christianise” the site.

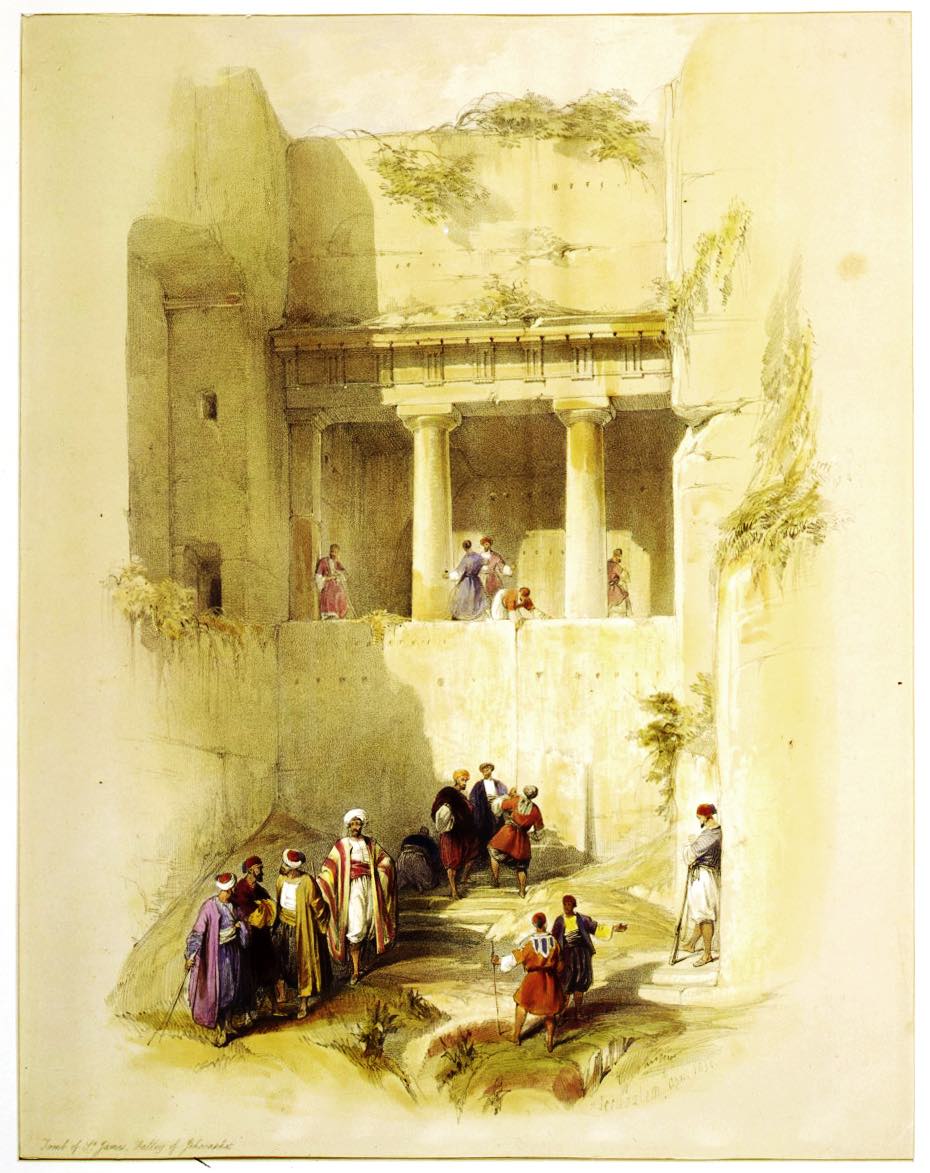

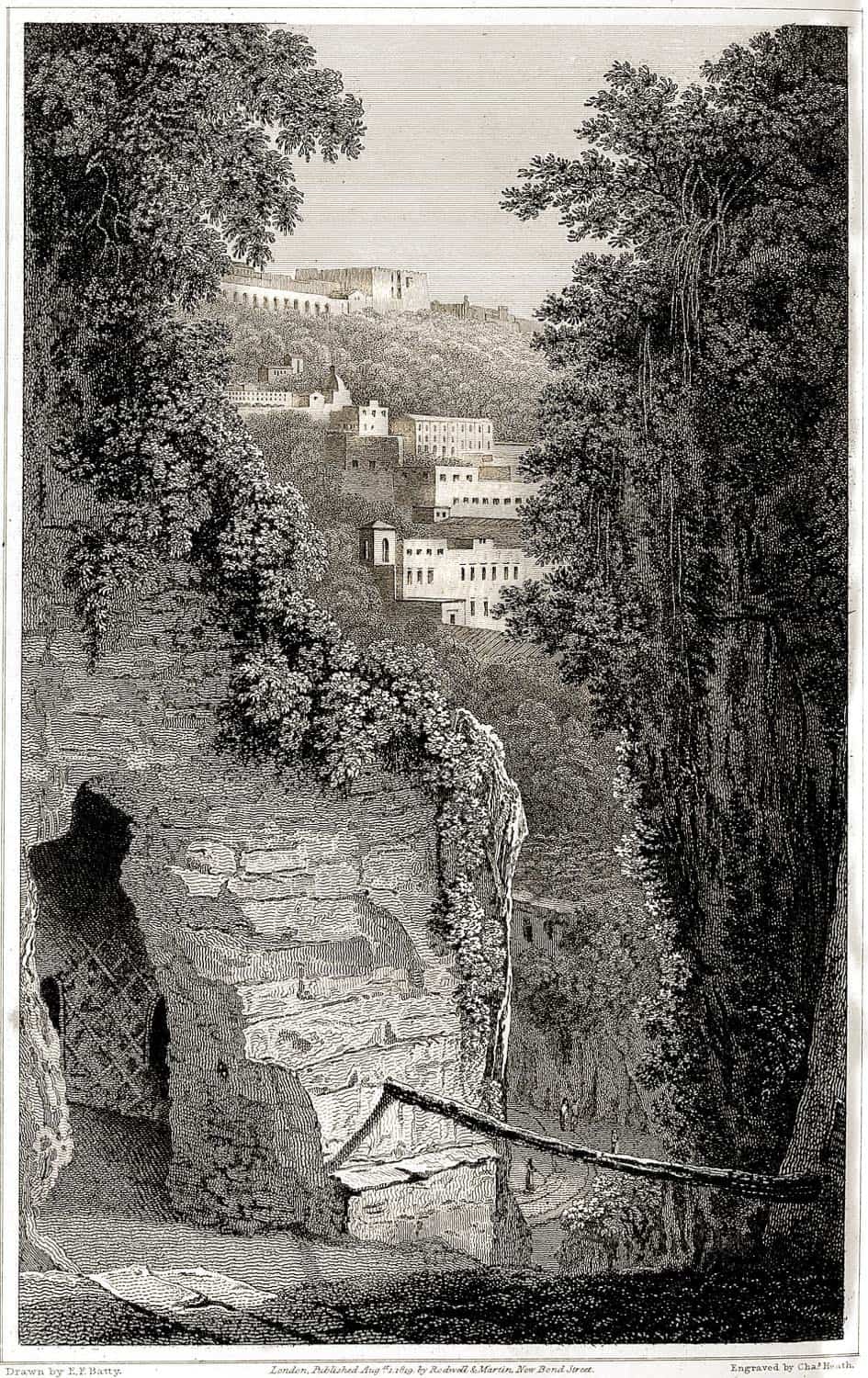

The Tomb of Virgil.

PLATE XLIV.

From St. Elmo begins the mount of Pausilippo. Between them is the church where the liquefaction of the blood of St. Januarius first took place, or was rather invented, if that juggle be not as old as Horace.

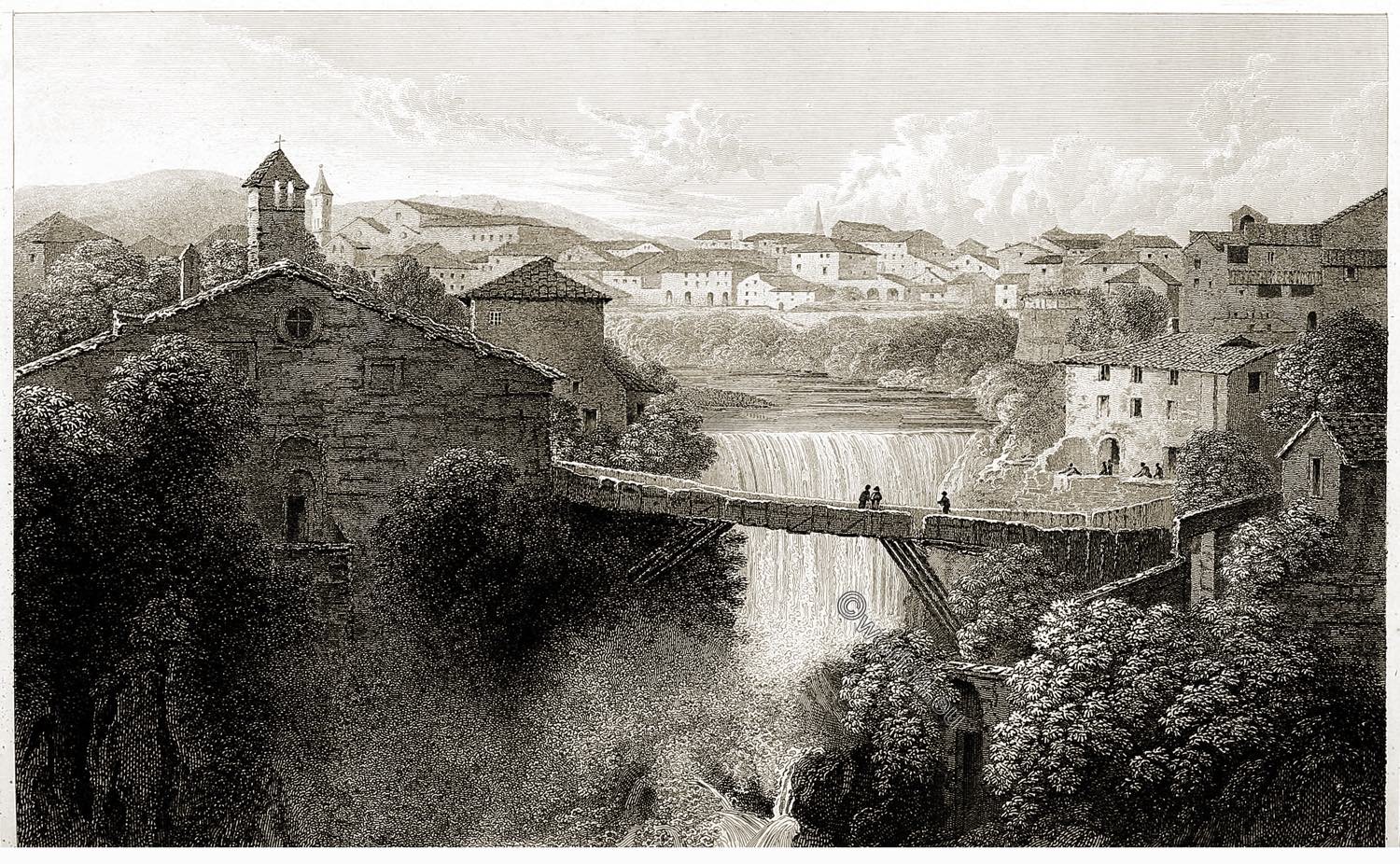

The mountain is a part of the ancient Colles Leucogei (Solfatara, Campi Flegrei), and is remarkable for the grotta or passage perforated through its mass to a distance of nearly half a mile, and forming part of the road from Naples to Puzzuoli. It appears to have been executed at a period as remote as the existence of the Cuman power, though the several improvements and repairs it has undergone, from time to time, have occasioned its being attributed to the various individuals under whom they have taken place: accordingly Varro would seem to give it to Lucullus; Strabo to Corceius; while Augustus, and even the magic of Virgil, have been cited as the authors of this useful work.

The passage is about twenty feet wide, and perhaps exceeds fifty in height. Perforations admit the light; but at one time of the year the setting sun illuminates and may be seen through its whole length.

Immediately over the grotta, and appearing in the left in this view, is the tomb of Virgil, at least the columbarium so called; for its identity is a great subject of controversy. Naples was a favorite spot with the poet, and hither, at his death, were conveyed his remains, by order of Augustus. Various authors pretend to have seen his sarcophagus, and one declares it to have been transported by a fugitive monarch to the Castel d’Uovo for the security it might have found in its sanctuary, but which the adverse fortune of its possessor could not afford; while the laurel tradition had sanctified with his name continued to flourish until the year 1776: but still nothing but tradition remains to uphold the charm spread around this little cell by association with the remembrance of the prince of poetry.

The building is placed upon the edge of the precipice, though sheltered by the rising rock behind, and shaded by the verdant foliage of the ilex, bending over its roof, and intertwining with the ivy which clothes its walls and festoons the steep beneath. The undecorated, or rather bare interior, presents no object for the gratification of classical curiosity, except the ancient epitaph put up by a modern native nobleman:

Mantua me genuit, Calabri rapuere, tenet nunc

Parthenope; cecini pascua, rura, duces.

(“Mantua begot me, Calabria carried me off, now Parthenope shelters me; I sang of shepherds, agriculture and heroes”.).

This, inscribed upon a marble slab, fronts the entrance. Eustace, anxious to cherish the conviction that he had visited the real tomb of Virgil, and hailed his sacred shade upon the spot where his ashes had long reposed, combats the opinion of Addison and Cluverius, who doubt its identity; deriving their doubts from a passage in Statius, considered by him as rather on the contrary confirmatory of the constant and uninterrupted tradition of the country, supported by the opinions and authority of numerous learned and intelligent antiquaries.

He adds, that his reader will learn with regret, that Virgil’s tomb, consecrated, as it ought to be, to genius and to meditation, is sometimes converted into the retreat of assassins or the lurking-place of Sbirri. Such, at least, was it at his visit, when wandering thither at the close of the day, he found it filled with armed men, whose threatening aspect, in so lonely a place, naturally excited his apprehension and alarm. They proved to be Sbirri, lying in wait for a murderer, who it was supposed made this his nightly asylum.

Source: Italian scenery from drawings made in 1817 by Elizabeth Frances Batty. London: Published by Rodwell & Martin, 1820.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.