THE CAPUCHINS.

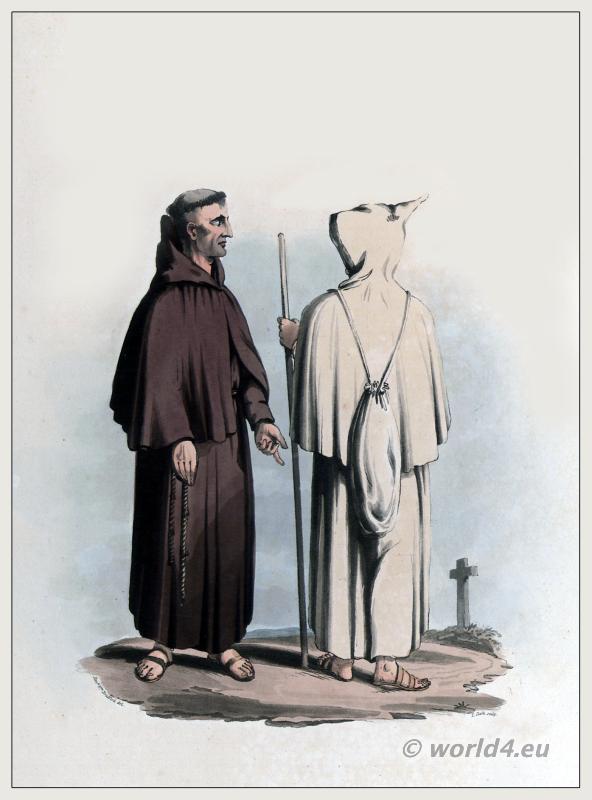

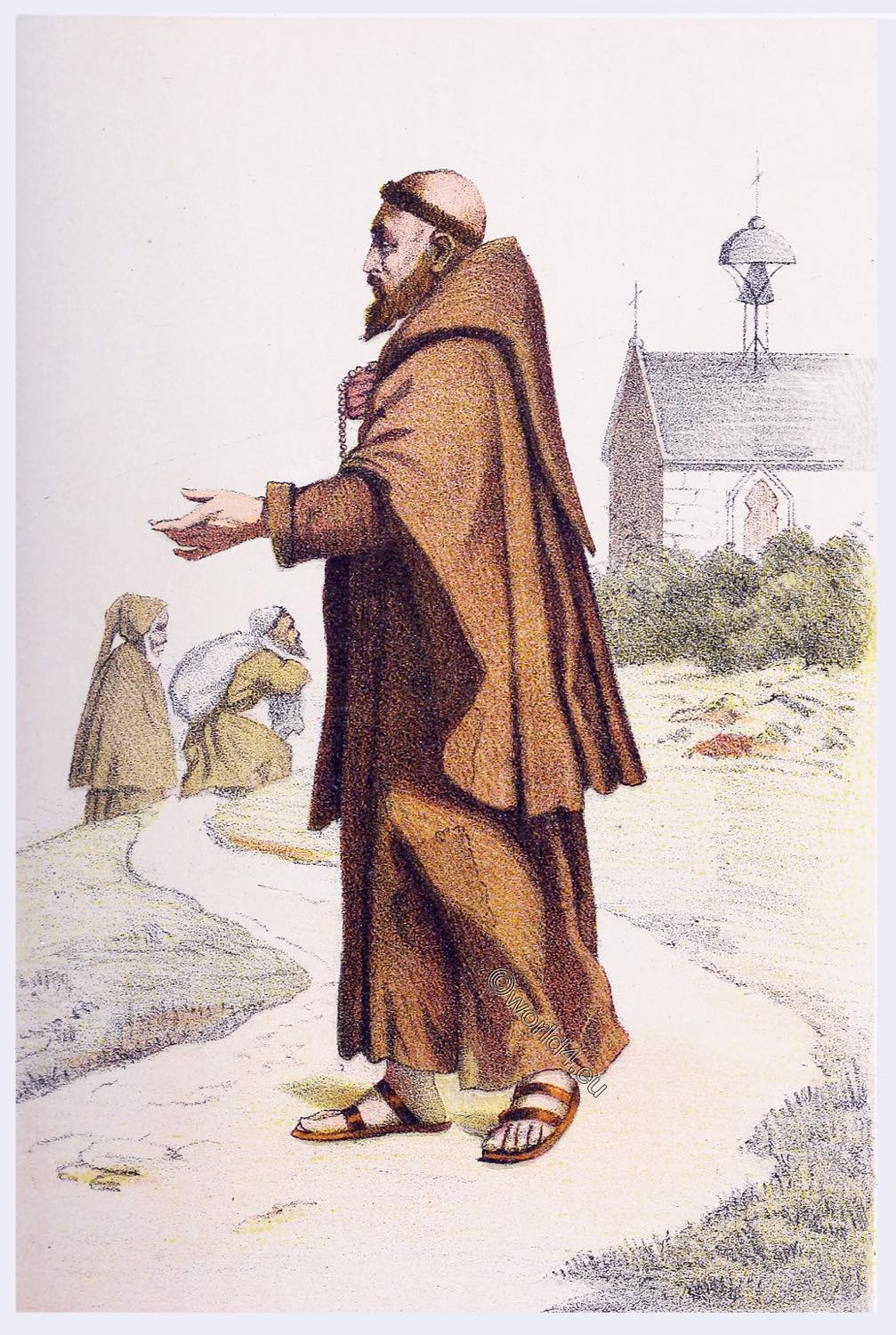

The Capuchins (OFMCap), actually Order of Friars Minor Capuchins (Latin: Ordo Fratrum Minorum Capuccinorum), are a Franciscan mendicant order in the Roman Catholic Church. The name of the order is derived from the distinctive hood of the Franciscan habit. It is one of the Franciscan orders and today – along with the Franciscans (OFM) and the Minorites (OFMConv) – forms one of the three large branches of the first order of St. Francis.

Content:

MATHEW DE BASSI. – LOUIS OF FOSSEMBRONE. – EXTERIOR PERSECUTIONS. – INTERNAL TROUBLES. – BERNARDINE OCHINO. – SPREAD OF THE ORDER. – ILLUSTRIOUS MEMBERS. – MISSIONS IN AMERICA.

AMONG the many branches of the Order of St. Francis, there is, perhaps, none more regular, more austere, and yet more singular than that of the men who are known throughout the Church as Capuchins. Mathew de Bassi, a religious of the Convent of Monte-Falco, belonging to the Observants, was the one to whom this institution owes its origin.

Desirous of wearing a habit, which, he believed, was exactly similar to that worn by the patriarch of all Franciscans himself, he left his convent, went to Pope Clement VII., and obtained from that pontiff the permission to put his desire into execution. Having presented himself before the chapter of the province of Ancona, the provincial treated him as an apostate and had him imprisoned.

Through the influence of Catherine Cibo, Duchess of Camerino, and niece of the Pope, he obtained his liberty. Two other Franciscans shared his views, but their provincials opposed them. The General of the order, however, approved of their plans, but counseled them to delay the execution thereof. In their impatience they had recourse to the Cardinal-Protector, who assured them that it was the wish of the Pope that such matters should be referred to the superiors of the orders. But the impatient religious would not delay; they obtained habits similar to that of Mathew de Bassi, and left their convents secretly to confer with their leader.

Having obtained letters of recommendation from the Duchess of Camerino, the two Friars addressed themselves to Clement VII., who referred them to the grand penitentiary, from whom they obtained a brief permitting Matthew de Bassi, together with Louis and Raphael of Fossembrone, to retire into a hermitage, and wear the habit they had chosen, even without the permission of their Superior, provided they had asked it. Louis and Raphael presented this brief to the Provincial of Ancona, but the latter obtained a counter-brief permitting him to proceed against these apostates, as he considered them to be. They, however, escaped from him, and took up their abode with the Camaldolese, near Massacio, who received them with great kindness.

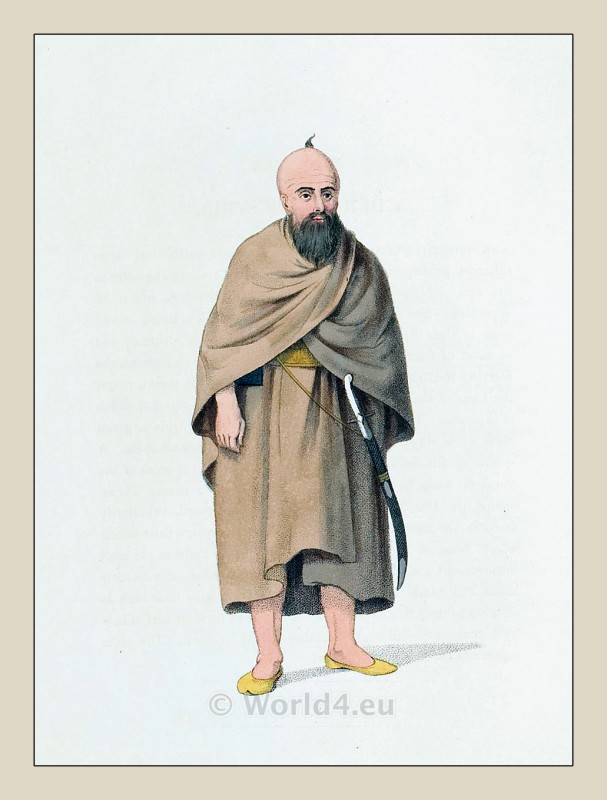

After being for a considerable time hunted down, as it were, by the Provincial, they were finally received under the jurisdiction of the Conventuals, in 1527. This was approved in the following year by the Pope, who permitted them to wear the peculiar hood of their choice and a long beard. It is from the year of the publication of this Bull of Clement VII. that the Order of Capuchins dates its beginning. Their number now began to increase, so that they were enabled to establish several convents. The conversions effected by their preaching, and the services rendered by them during the contagious disease which ravaged Italy in 1528, gained for them universal esteem. Mathew de Bassi was elected first Vicar-General, under the jurisdiction of the General of the Conventuals, and constitutions were drawn up for the government of the religious. It was decreed among other things that they should recite the Divine Office without chant, and say Matins at midnight. There was to be meditation in the morning and in. the evening, and on certain days the discipline was to be taken. The utmost poverty was also prescribed.

Mathew de Bassi having resigned his office, Louis of Fossembrone succeeded him. Hélyot says that the latter refused to convoke a general chapter at the request of his brethren, his desire of holding the· reins of government affording him several pretexts for his refusal. It is strange that the first two Capuchins should have left the order which, owed its origin to them.

The facts, as given by Hélyot, are as follows: Louis of Fossembrone, beholding himself forced by the will of the Pope to convene a general chapter, hoped that he would be continued in his office, but to his great chagrin the chapter, which was held at Rome in 1535, elected Bernardine d’Asti to fill the office of Vicar-General. The ex-Vicar-General now publicly gave vent to his feelings, and reproached the Capuchins with having treated him with the greatest ingratitude.

The Vicar-General and the definitors who had been elected assembled and divided the congregation into provinces, making at the same time other regulations. Louis of Fossem.. brone refused to be present at this meeting, laid his complaints before the Pope, and requested that another general chapter be held. The’ Sovereign Pontiff ordered the convocation of the general chapter which had been asked for, and it was held under the presidency of Cardinal de Trani. Bernardino d’Asti was again elected, and this time Fossembrone broke out into such invectives against the order that the Cardinal ejected him from the chapter, and the Pope confirmed the election of Bernardine. Louis of Fossembrone finally refusing to acknowledge the new Vicar-General, and to submit to obedience, was disgracefully chased away from the order by a sentence of the superiors, which the Pope confirmed.

The liberty-loving Mathew de Bassi, who had resigned the Vicariate-General in order to enjoy greater freedom, having come to the convent of Rome in 1537, learned that a Bull of the Pope excommunicated all those who, without living in the monasteries subject to the VicarGeneral of the Capuchins, nevertheless wore their hood. Hearing this, he cut off the half of his hood, and left the Capuchins under the pretext of continuing his preaching in conformity with the permission which had been granted him by Clement VII. It thus happened that those who had commenced the institute of the Capuchins broke with the order they had been instrumental in founding.

Bernardine d’Asti was succeeded in the government of his order by Bernardine Ochino, who had entered the congregation in 1534. He had received the habit from the Observantines, but having apostatized from their order, he applied himself to the study of medicine at Perugia. After some years, touched with repentance, he returned to the Observantines, but left them again within a short time to join the Capuchins, who received him with joy, and afterwards elected him Vicar-General.

He governed the order with such prudence and caused the rule to be observed with such exactitude that he was elected a second time, in 1541. He was considered the ablest preacher of his time, though his sermons consisted for the greater part of beautiful language without substance. His know ledge was so superficial that he scarcely knew Latin. Nevertheless the people and the princes revered him as a saint, and loaded him with honors. His brethren respected him no less on account of his zeal for the Regular Observance and his great virtues. However, the honors he had received elated him, and he began to aspire to the highest dignities of the Church.

Seeing that the Pope did not appear as much convinced of his merit as he was himself, he began adroitly to make use in his sermons of expressions derogatory to the authority of the Sovereign Pontiff. This caused him to be summoned to Rome, but he refused to go, and in order to escape prosecution on the part of the court of Rome, he abandoned his Capuchin habit, and, in 1542, took refuge at Geneva, which was in the hands of the Calvinists. Here he married a woman from Lucca who had followed him. Leaving Geneva, he wandered from place to place, teaching all manner of new doctrine, even polygamy, until he finally died of the pestilence in Moravia, at the same time as his wife, two daughters, and a son. Boverius, in his Annals of the Capuchins, makes him die at Geneva. after having retracted his errors, but Hélyot does not admit this as probable.

The apostasy of Ochino caused a certain amount of damage to the Capuchins, as they became suspected of heresy, and the consequence was that the ministry of preaching was forbidden them for two years. After this ordeal, through which they had passed, their congregation spread only in Italy, for Paul III., in 1537, had forbidden them to establish themselves beyond the Alps. This decree was later on revoked by Gregory XIII., who at the request of Charles IX. allowed them to settle in France. Paul V. permitted them to accept convents in Spain, and they finally crossed the seas and obtained a portion of the foreign missions.

In 1619 Paul V. exempted them from the jurisdiction of the Conventuals, to whom they had thus far been subject, and gave to their Vicar-General the title of General.

The Capuchins have until the present day persevered in the exact observance of the rule of their holy patriarch. Though little in conformity with the spirit of the world, especially with that of our century of refinement, culture, and luxury, the order has produced men of high sanctity and eminent learning. St. Felix of Cantalicio, a simple lay-brother, and a friend of St. Philip Neri, was a Capuchin; Cardinal Anthony Barberini, brother of Urban VIII., was also a member of this order. The celebrated Joseph Le Clerc du Tremblai, called the Black Cardinal, a Capuchin friar, was a most influential man in France during the reign of Louis XIII., and in the time of Cardinal de Richelieu. The order has also been rendered illustrious by a number of distinguished preachers and men of great learning. Among those who left a high position in life to clothe themselves with the humble garb of St. Francis in the Capuchin order, we mention Alfonso d’Este, Duke of Modena, who became a Capuchin in 1626, and Henry, Duke of Joyeuse, and marshall of France, who entered the order in 1587, but left it again in 1592, with papal dispensation, to join the league and head the troops of Languedoc. However, he returned to the Capuchins, and spent the rest of his days in great piety. He died among them in 1608. He was the father of the Princess de Montpensier, wife of Charles de Lorraine, Duke of Guise.

The Capuchins, who at an earlier period had done missionary duties in Maine and in Louisiana, were resurrected in the United States in the diocese of Milwaukee by the Rev. Bonaventure Frey and the Rev. F. Haas. In 1864 these religious established the ecclesiastical seminary of St. Laurence of Brindisi in Wisconsin. They obtained several other’ foundations in this country, not only in Wisconsin, but also in Michigan and New York. They possess three establishments in the latter city.

In the early part of the eighteenth century the Capuchins had served as military chaplains to the French in what is now the State of Mississippi; they also attended to all the settlements and missions west of the Mississippi, from its mouth to a point opposite the mouth of the Ohio. Their Superior resided at New Orleans, and he was Vicar-General of the Bishop of Quebec. These Fathers belonged to the province of Champagne *). In the last century they also possessed missions in the French West Indies.

*) De Courcy,-Shea.

Source: History of religious orders. A compendious and popular sketch of the rise and progress of the principal monastic, canonical, military, mendicant, and clerical orders and congregations of the Eastern and Western churches, together with a brief history of the Catholic church in relation to religious orders by Charles Warren Currier. New York, Murphy & McCarthy, 1894.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.