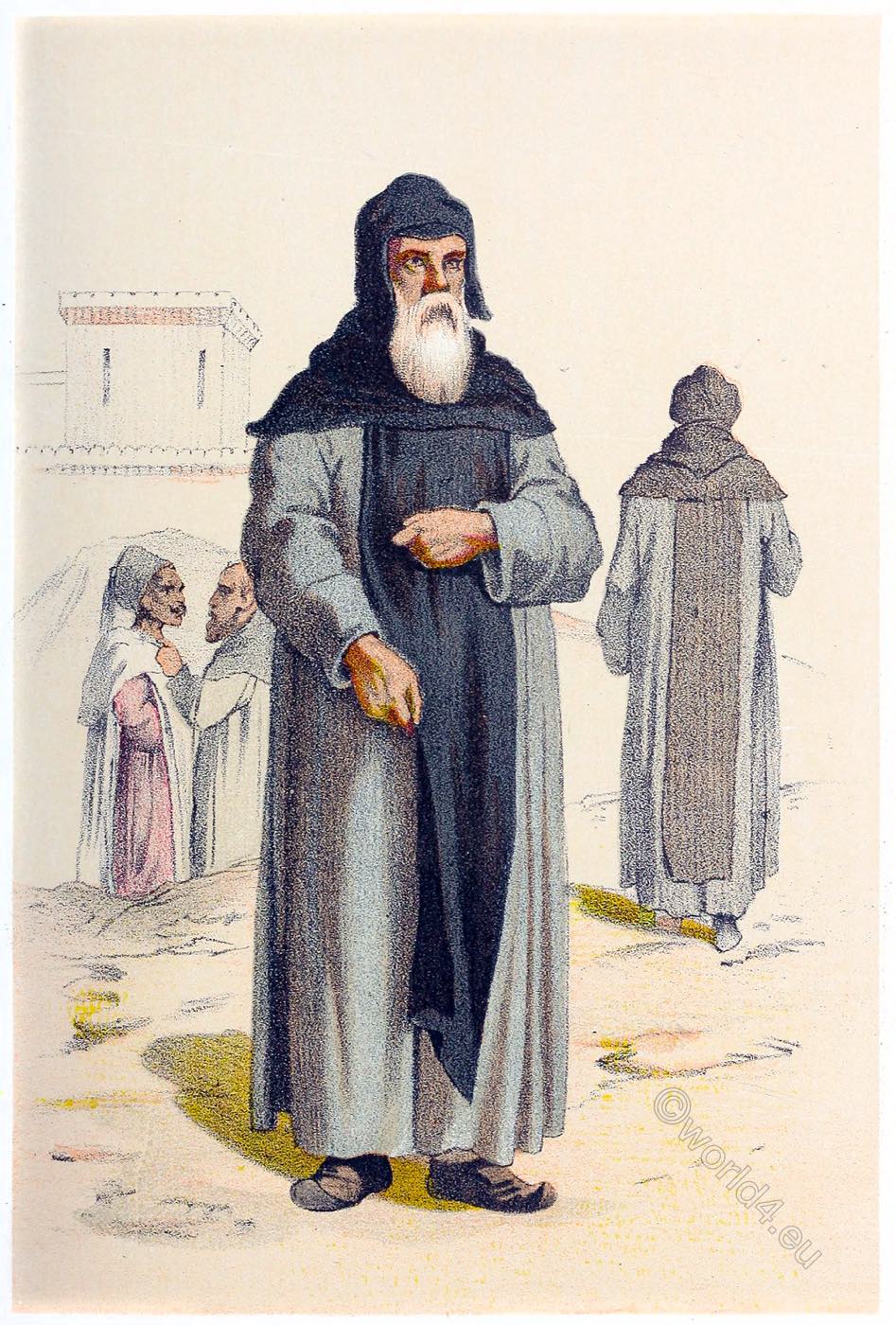

MONKS OF ST. BASIL.

LIFE OF ST. BASIL. – PROPAGATION OF HIS ORDER. – MUSCOVITE MONKS. – CONVERSION OF RUSSIAN MONKS. – REFORMATION OF THE ORDER IN ITALY. – BASILIANS IN SPAIN. – BASILIAN NUNS. – ARMENIAN MONKS. – MARONITES.

ST. Basil is justly called the patriarch of the monks of the East: for it was he who perfected the monastic institution in the Oriental Church and bound the monks by vows. He belonged to a family of saints, and counted them among his nearest relatives. The city of Caesarea in Cappadocia had the honor of being the place of birth of the saint, who first beheld the light about the year 329. At Caesarea in Palestine he made the acquaintance of St. Gregory of Nazianzen, with whom he contracted a friendship that was to unite these two saints until death. They followed their studies together in the classic city of Athens, where the unfortunate nephew of Constantine, Julian the Apostate, was their fellow-pupil.

After many years spent in study, feeling in his soul a growing antipathy for the vanities of life, St. Basil travelled through Egypt, Palestine, Syria, and Mesopotamia, where he studied the religious life and made the acquaintance of many of the saints who professed it.

Eusebius, bishop of Caesarea, ordained him priest, but having at a later period conceived a feeling of jealousy against the saint, the latter once more retired into solitude. After three years he was again recalled to Caesarea, and Eusebius, acknowledging his extraordinary talents, placed the entire management of the diocese in his hands, and allowed himself to be guided by the counsels of the saint. After the death of Eusebius, St. Basil was chosen bishop of Caesarea. His elevation to the episcopacy became the signal of persecution which the Arians excited against him, and which he endured for a long time. He died January 1st, 379.

The precise epoch of the foundation of the Order of St. Basil forms a subject of controversy among its historians. Hélyot, following Herman, Tillemont, and others, places it about the year 358. In that year the saint retired into a desert of the Province of Pontus, whither he was followed by St. Gregory of Nazianzen, and where his sister, St. Macrina, had established a convent. There St. Basil built his first monastery of the monks of his order, to whom he gave a written rule.

At the present day, the Basilian monks are divided into Catholics and schismatics. The schismatical monks of the Order of St. Basil are to be found principally in the Russian empire. The religious life was introduced into that country with the Christian religion itself, which the Russians received from the Greeks, with whom they afterwards separated from the See of Rome.

The Order of St. Basil soon spread over the East, and it was even introduced into Italy. According to Dom Alphonsus Clavel and other historians of the order, the rule was approved by Pope Liberius in 363, by Pope Damasus in 366, and later by Saint Leo at the request of the emperor Marcian. It was subsequently approved by several other popes, and it made immense progress even during the lifetime of the holy founder. It underwent many vicissitudes in the East, and it was subject to great persecution during the reign of the emperor Constantinus Copronymus (Byzantine emperor from 741 to 775), who waged a furious war against the veneration of images.

Although the Muscovite monks follow the rule of Saint Basil, they have nevertheless changed it in various points. Monks and nuns are very numerous throughout Russia, and it is always from among the former who, of course, are celibates, that the episcopacy is recruited. Many of the Russian monks lead a very austere life; they take the three vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. Those who break them and apostatize from the religious state are punished by perpetual imprisonment, nor can the bishops dispense anyone from a vow.

In the year 1595, many of the Basilian monks in White Russia returned to the communion of the Latin Church, and they were admitted by Pope Clement VIII. The schismatics, however, subjected them to a cruel persecution, during which St. Josaphat Kuncevizzi, Archbishop of Polocko, suffered martyrdom on November 12, 1623. The Basilian monks in Russia, subject to the See of Rome, are under the jurisdiction of a chief archimandrite, chosen by themselves, in virtue of a privilege granted to them by Pope Urban VIII., October 4th, 1624. They are, nevertheless to a certain extent, subject to the jurisdiction of the metropolitan. Their occupation consists principally in preaching, the administration of the sacraments, and other ecclesiastical functions. Their habit differs from that of the Muscovite monks; but they follow the Greek rite, and say the office in the Slavonic language.

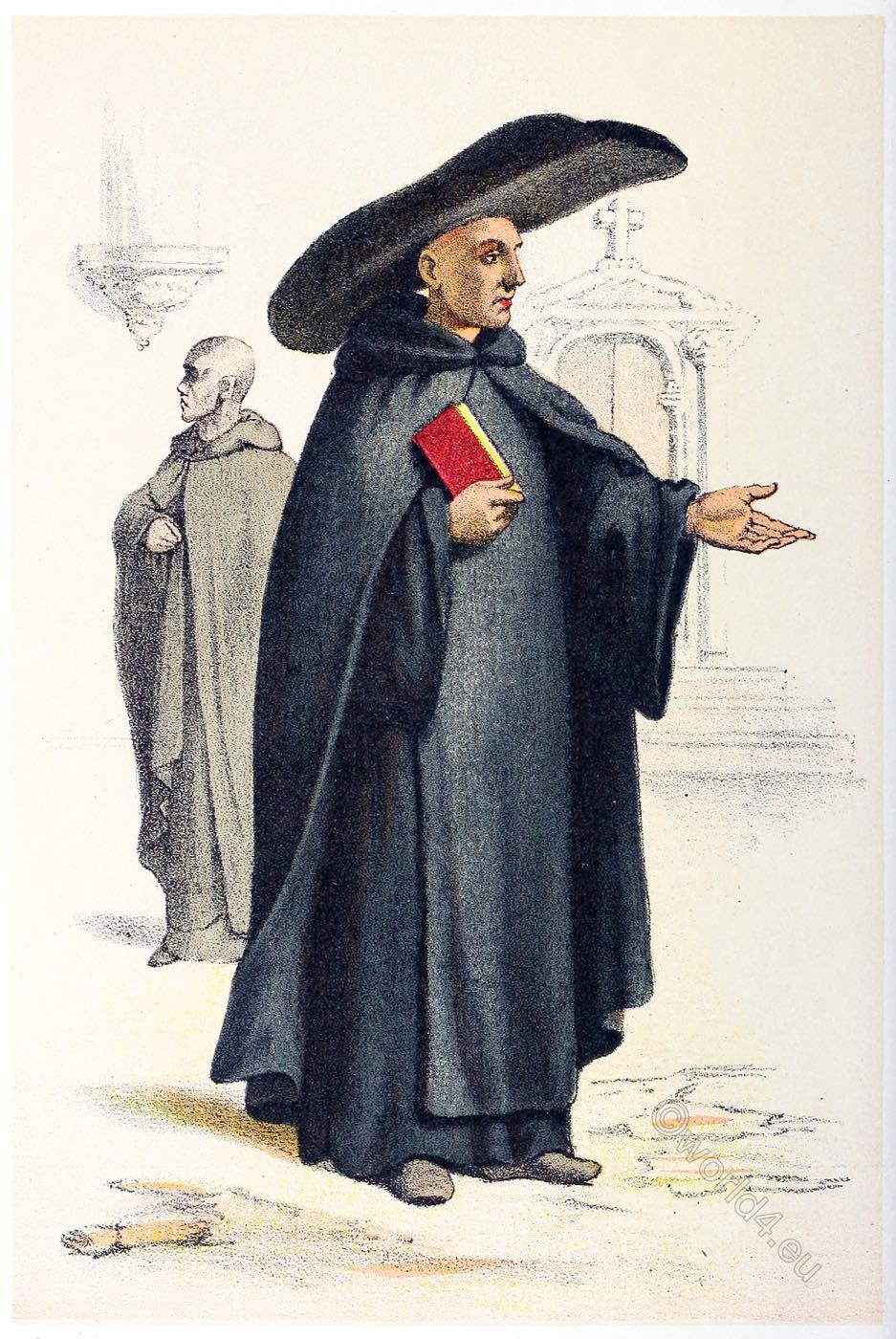

The rule of St. Basil had, at an early period, been translated into Latin by Rufinus, and it was immediately introduced into the West, especially into Italy, where its monasteries soon became very numerous. About the year 1573, it had greatly degenerated in the last named country, and Pope Gregory XIII. endeavored to reform it. He united together into one body all the monasteries of the order in Italy, Spain, and other provinces subject to the Holy See, and decreed that every three years a general chapter should be held, in which a general, visitors, a procurator-general, and other officers should be elected. All the provinces united to the Latin Church he submitted to the authority of the general of the order. He also accorded them many privileges which were afterwards confirmed by Clement VIII. and Paul V.

In the provinces of Sicily, Calabria, and Rome the Basilian monks follow the Greek rite, but conform in several details to that of the Latins, consecrating in unleavened bread, using vestments like those of the Latin Church, and adding to the Creed the words: “Qui ex Patre Filioque procedit.” Some religious, however, in these provinces, by special privilege, conform to the Latin rite. At a later period it was decreed that the general chapters should be held only every six years.

The Basilian monks in Italy fast in Advent and every Friday of the year; they eat meat once on three days of the week, namely, on Sunday, Tuesday, and Thursday. They work in common at certain hours of the day. On Saturday they accuse themselves of their faults in chapter. Their habit much resembles that of the Benedictines.

There are also Basilian monks in the Austrian empire. If the order had been introduced into Spain at an early period, it again disappeared. During the reign of Pope Pius IV. (1559-1565) it was once more reestablished in that country. Certain religious men in the diocese of Jaen, having petitioned that Pope to be admitted into the order, as they had already followed the rule of St. Basil, their request was granted by a bull of January 18th, 1561. Their superior, Father Bernard de la Cruz, made his profession in the hands of the abbot of Grotta Ferrata, and received that of his brethren.

A few years later, Father Matthew de la Fuente introduced a reform of the order at Tardon and at Valle de Guillos. Pope Gregory XIII. united those two monasteries with that of Our Lady of Oviedo in the diocese of Jaen into a province, to which the other monasteries of Spain were to belong, and subjected them to the jurisdiction of the abbot-general of the order in Italy. Clement VIII., however, again separated the two reformed monasteries of Tardon and Valle de Guillos from the others, forbidding the latter to receive novices. This prohibition was afterwards revoked, and the monasteries were divided into the provinces of Castile and Andalusia, subject to a vicar-general under the jurisdiction of the general of the order. The Spanish Basilians follow the Latin rite. The superiors of their monasteries hold their office for three years, after which they cannot be re-elected until six years have elapsed. Each province holds a chapter every three years. They abstain from meat only on the days of ecclesiastical abstinence, but fast every Friday in the year, during Advent and on the vigils of the feasts of the Blessed Virgin and of Saint Basil. They take the discipline every Wednesday and Friday in Advent, and on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays in Lent. Twice a week they work in common. In summer they recite Matins at midnight, and in winter at three in the morning. They make an hour’s meditation after Prime, and another in the evening, after Compline. Every Friday they accuse themselves in chapter of faults committed against the rule. Their habit consists of a black cassock and scapular, and a hood. In choir and out of their monastery they wear a black cowl. The lay brothers have the same habit, with the exception of the cowl. They have also oblates, who wear the habit without the hood.

In 1603, the monasteries of Tardon and Valle de Guillos, where the rigorous observance of the Basilian rule prevailed, were separated from the other monasteries, and formed a branch of the Basilian order known as that of the Reformed Basilians of Tardon. It never spread beyond a few monasteries in Spain. These religious unite manual labor with prayer, and in their fasts and abstinences resemble the Basilian monks of Italy. They do not wear the cowl, which garment Clement VIII. thought is not in accordance with the rule of St. Basil. They were submitted by the same Pope to the jurisdiction of the general.

The Order of Saint Basil has given to the Church several popes and a great number of bishops. Many of its members have been canonized.

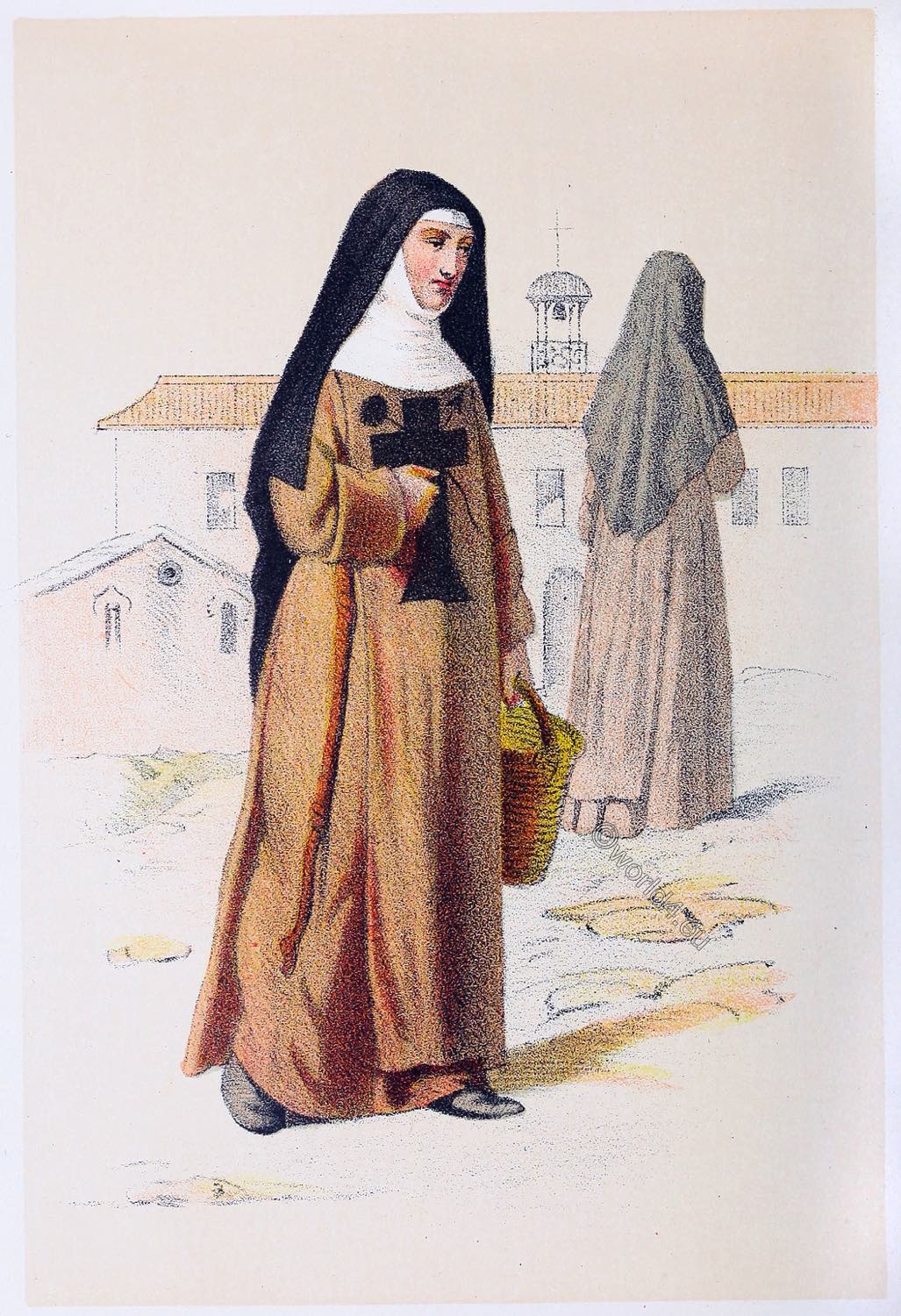

There exist also monasteries of Basilian nuns. The first convent of these virgins was founded by Saint Macrina, sister of Saint Basil, who gave rules to it as well as to the other monasteries of nuns which he established. These religious also suffered during the persecution of Constantine Copronymus.

The constitutions of the monastery built in 1118, at Constantinople, by the empress Irene, give an idea of the regular observance which was practiced by the Basilian nuns in the Greek Church. The religious were to be received without a dowry, but any spontaneously”, offered gift might be accepted. The abbess was chosen by the community, and might be deposed if found unworthy of governing. They had a spiritual father to whom they rendered an account of their thoughts, and two priests, taken from among the monks, were appointed to administer the sacraments to them. The temporal administration of the goods of the monastery was entrusted to an econome. While the nuns worked, one of their number read to them. They slept in a dormitory, observed great poverty, and practiced rigorous abstinence. They were not entirely cloistered, and they were allowed to leave their monastery in order to visit their sick relatives. Women were allowed to enter their monastery, but they received the visits of men at the door, and they were always accompanied on such occasions by some of the ancient religious. They were allowed the use of the bath, which, certainly, is not inconsistent with sanctity, as cleanliness is next to godliness. In illness a physician was summoned.

There are a considerable number of schismatic Basilian nuns in Russia and other oriental countries. Religious women following this rule, and in communion with the See of Rome, exist in Poland and in Italy. The latter follow at present the Latin rite, with the exception of the monastery of Philantropos at Messina, where the Greek rite has always been observed.

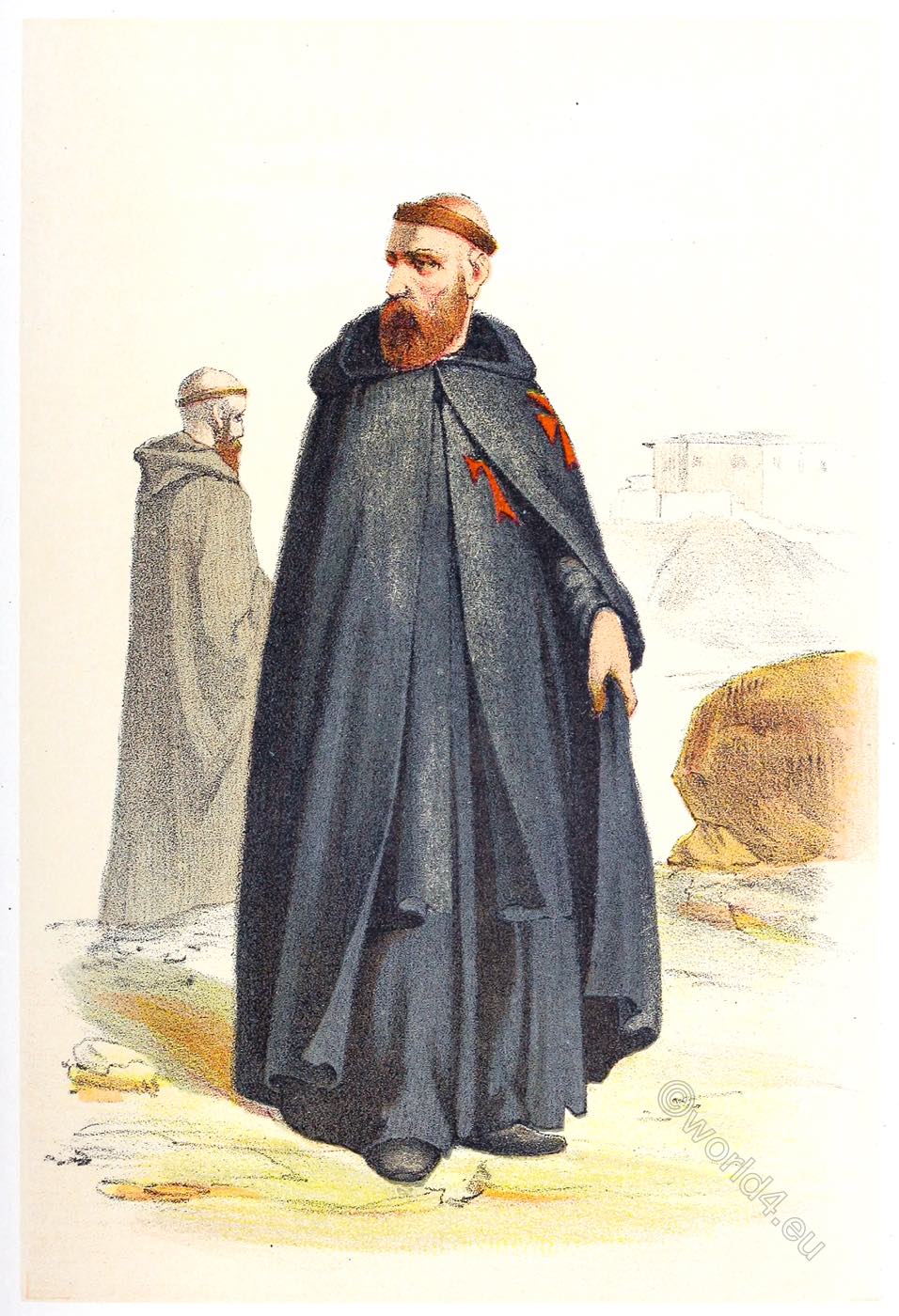

A great number of monks are to be found among the schismatical Armenians. They belong to the Order of St. Anthony and to that of St. Basil. The former dwell in the deserts and lead very austere lives, surpassing in rigor the most reformed monasteries of Europe. According to Hélyot, they never eat meat or drink wine, except at Easter. They fast all the year round, even on Sundays, and eat only once a day. They live on roots and vegetables, and abstain from fish, milk, and even oil. They never leave their monasteries, and speak to no one except through the porter. They dwell in separate cells, and they are constantly at work except during the hours of the Office and other exercises of the community. They are all laymen with the exception of five or six priests in each monastery. For their Office they recite nightly the entire Psalter, standing with no support but a species of crutch. According to this description, which Hélyot says was given to him by two Armenian priests, these monks have preserved the mode of life of the ancient solitaries better than any other at present existing religious.

The monks of the Order of St. Basil among the Armenians, as the same author remarks, are not as exact observers of their rule as those of St. Anthony. Their monasteries are generally situated near cities, and it is from their number that the ranks of the higher clergy are recruited. The Armenian monks of St. Basil also possess monasteries in Jerusalem.

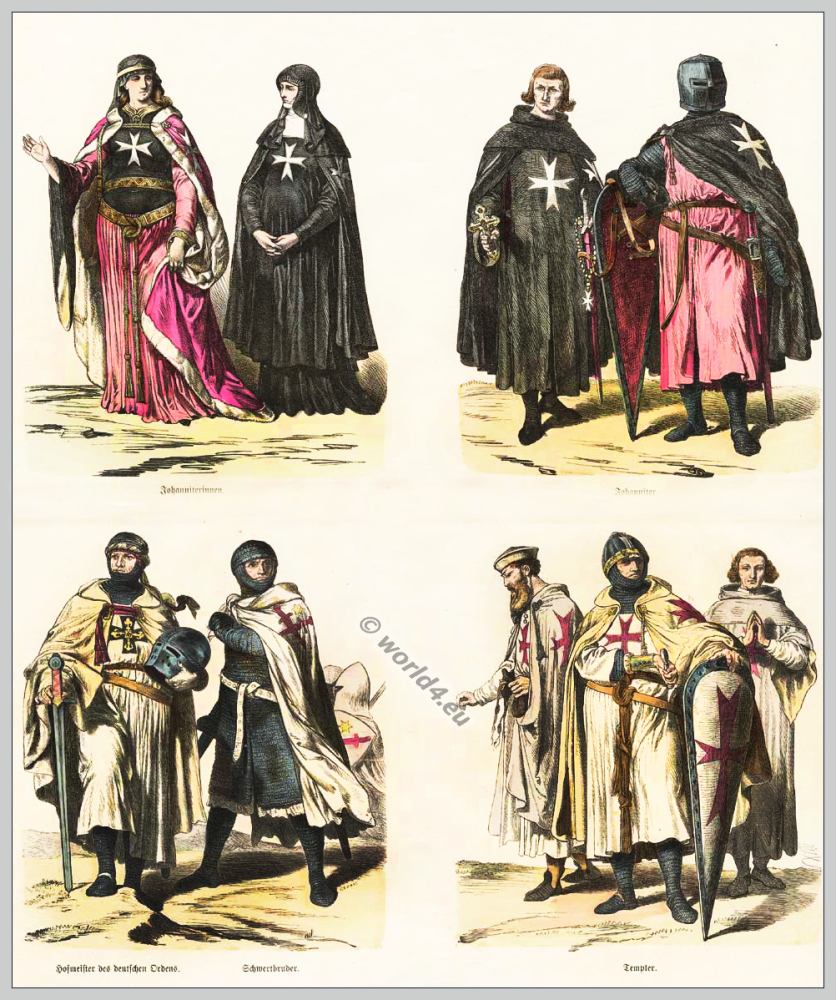

At the close of the 18th century, several Armenian monks of the Order of St. Anthony were converted to the Catholic faith, and they established themselves in Morea, where the republic of Venice gave them a monastery in the city of Modon. They continued, nevertheless, to follow the Armenian rite. Their habit is black, like that of the other monks of Armenia, but they wear on the left side a red cross as a token of their willingness to shed their blood for the faith of Christ.

In the year 1307, several Catholic Armenian monks of the Order of St. Basil, flying from the persecution of the Turks, settled in Genoa, where they built a church in honor of the Blessed Virgin and St. Bartholomew, whence they were called Bartholomites. They afterwards established several other monasteries in Italy. In course of time, they changed their monastic habit for that worn by the lay-brothers of the Order of St. Dominic. They began to conform to the Latin Church for the recitation of the Divine Office, and to celebrate Mass according to the manner of the Dominicans, whose constitutions they adopted. They abandoned the rule of St. Basil for that of St. Augustine. Pope Innocent VI. approved of these changes in 1356. Boniface IX. forbade these monks to pass over to any other order except that of the Carthusians, and made them participants in all the privileges of the Order of St. Dominic. Innocent X. seeing that they had grown greatly relaxed, and that they were much reduced in numbers, suppressed their order in 1650, permitting them to pass over to other orders.

Another branch of the Order of St. Basil had also become incorporated into that of St. Dominic. About the year 1328, Father Dominic of Bologna, of the last named order, had been sent to Armenia by Pope John XXII. His example and that of his companions exercised such powerful influence over the superior of one of the Armenian monasteries, that by his intervention many schismatic monks were converted to Catholicity. One of the superiors instituted an order to which the name of United Brethren of Saint Gregory the Illuminator was given. Its members adopted the rule of St. Augustine and the Dominican constitutions, together with the habit of the Dominican lay-brothers. This was approved of by Pope John XXII. The order spread greatly throughout Armenia and Georgia. In 1356, the brethren obtained from Pope Innocent VI. permission to pass over to the Order of St. Dominic, of which they henceforward formed a province.

There are in Egypt a number of schismatic monks of the Coptic rite who belong to the Order of St. Anthony, and lead a very austere life. Their monasteries are, for the greater part, situated in the desert, the principal of these being the monasteries of St. Anthony, St. George, and St. Macarius. They may be considered a remnant of the ancient solitaries of Egypt.

Source: History of religious orders. A compendious and popular sketch of the rise and progress of the principal monastic, canonical, military, mendicant, and clerical orders and congregations of the Eastern and Western churches, together with a brief history of the Catholic church in relation to religious orders by Charles Warren Currier. New York, Murphy & McCarthy, 1894.