French Fashion of the Middle Ages.

Reigns of John II and of Charles V. 1350 to 1380.

Table of Content:

The States of Languedoc – A young French lady in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries – Low dresses – Saying of a mercer – Damoiselles – Garnaches and garde-corps – Le Parement des dames – Social distinctions – High character is worth more than gilded belt – Precious stones – The castles and other dwellings of the middle ages – Splendid furniture – Humble abodes of the poor – Evening assemblies.

The States of Languedoc.

NOTWITHSTANDING the efforts of legislation, extravagant expenditure on dress continued as great as ever, while the large majority of the French nation was suffering from great poverty. In 1356 the States of Languedoc forbade the use of rich clothes until the release of King John (Jean II., le Bon), who was a prisoner of war in England.

But noble lords and ladies insulted the nation in its hour of misfortune by their prodigality, and defied the regulations that forbade them to wear gold, silver, or fur on their garments or open hoods, or any other sort of ornamentation.

As for widows, they found themselves unable to oppose the established custom. They therefore conformed to the regulation forbidding them to wear voilettes, crépines, and couvre-chefs.

In like manner with nuns, they never appeared in public without a guimpe that entirely concealed the head, ears, chin, and throat. There seems, however, to have been no particular etiquette for the nobility as to mourning, before the reign of Charles V. we may endeavour to sketch the portrait of a lady as she existed in feudal times, by means of the scanty materials in our possession, for we have no paintings, and very few sculptures of the time, only a few learned writers who supply us with valuable hints.

We know, however, that the gowns of the fourteenth century were of the same shape as those of the thirteenth; we also know that the Frenchwoman of the period began to discover the beauty of a small waist, and endeavoured to compress her own by means of lacing, and, finally, we know that, dating from the later years of the reign of Charles VI. a habit of uncovering the shoulders to an extent that at times became immodest was adopted. Their “couvre-chefs” of silk were made by a special class of workwomen, called “makers of couvre-chefs.” The couvrechefs of Rheims were specially renowned.

Saying of a mercer

There were no milliners in Paris either in the thirteenth or the fourteenth centuries. The haberdashers, of whom I have already spoken, sold articles of dress, scents, and elegant finery. In the “Dit d’un Mercier” we find the following lines: – J’ai les mignotes ceinturêtes, J’ai beaux ganz à damoiselêtes, J’ai ganz forrez, doubles et sangles, J’ai de bonnes boucles à angles; J’ai chainêtes de fer belès, J’ai bonnes cordes à vleles; J’ai les guimpes ensafranées, J’ai aiguilles encharnelées, J’ai escrins à mêtre joiax, J’ai borses de cuir à noiax, etc.

(The mercer’s list includes so many articles of which the names are obsolete, that it is not possible to translate it.)

At mercers’ shops, besides, ladies bought molekin, fine cambric, ruffs for the neck with gold buttons, the tressons or tressoirs that they were fond of twisting in their hair, and gold or pearl embroideries used for head-dresses, or for ornament generally, the silken or velvet gown being even bordered with them sometimes.

Damoiselles

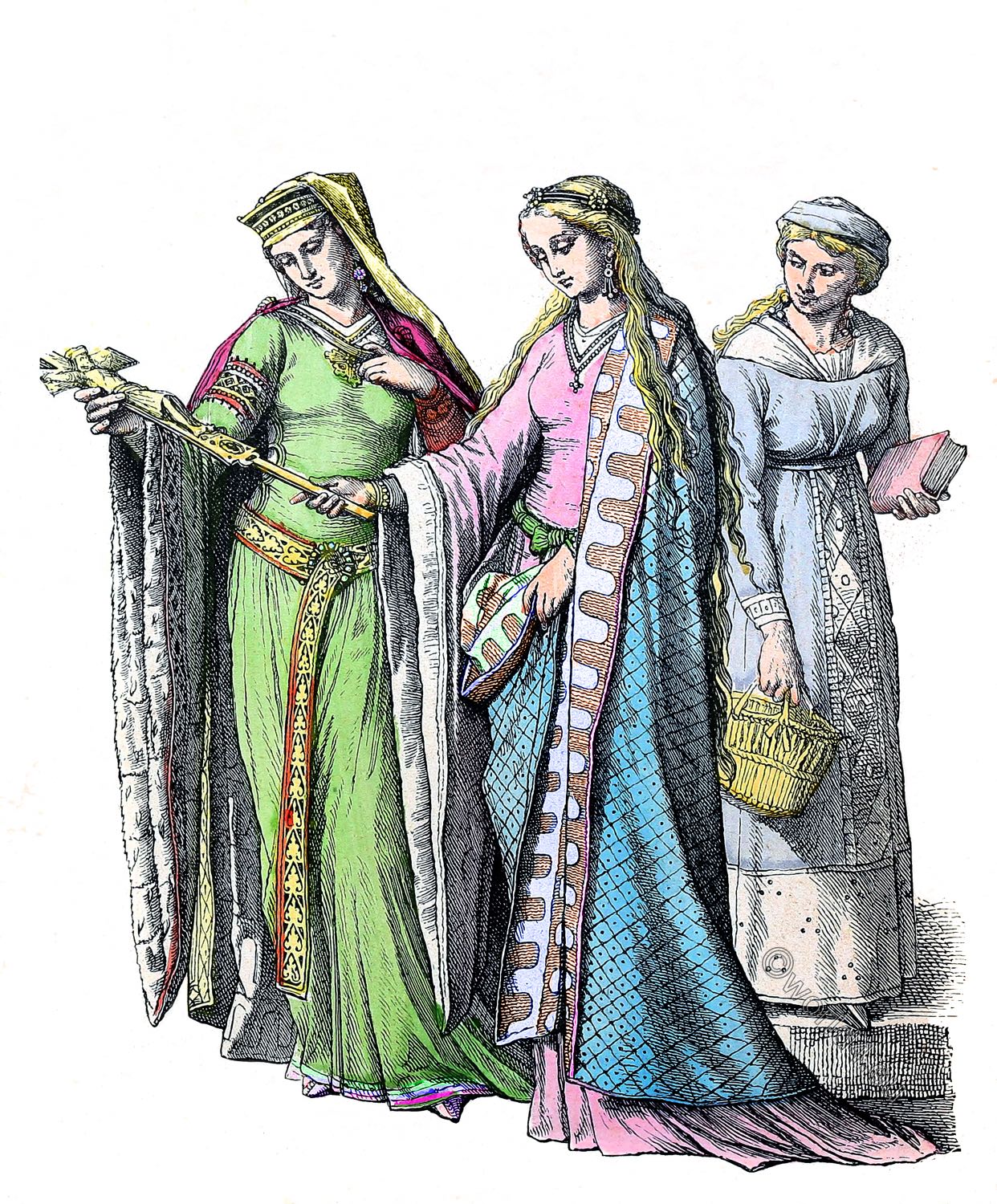

Lay figures, called “damoiselles,” were used for fitting on ladies’ dresses and other garments. A young Frenchwoman in the fourteenth century wore her hair twisted round her head, with a black ribbon; a white dress embroidered in silver, bordered at the throat, shoulders, and elbows, and at the edge of the skirt with a fillet of gold. Small sleeves reaching from elbow to wrist were in red and white check, bordered with a double fillet of gold. Her shoes were black.

Sometimes her hair was confined by a white veil, mingled with pearl-embroidered ribbon; at other times she wore a coronet of beads, and her hair flowed loose over her shoulders. She frequently appeared in a short sleeveless tunic, called “corset fendu.” Frequently, too, her hair was parted simply in two, and the long plaits arranged on the forehead. To this she would add a “fronteau,” that is to say, either a tiara of beads or a circlet of gold. She made “attars” for herself, or pads stuffed in the shape of hearts, clubs, or horns.

A young girl of high birth wore the arms of her family; a married woman wore both her husband’s and her own. Montfaucon, in his” Antiquités de la Couronne de France,” gives us a drawing of an emblazoned gown belonging to a noble lady; and in an ancient Bible we find a picture of a woman on whose hair is a ribbon of gold tissue, and above it a small yellow cap with gold buttons.

The upper dress is bordered on the bosom with ermine and gold bands, the skirt is of silver cloth, bearing a lion rampant and three red stars. The under garment, of a dull yellow, is confined by a gold band. The National Library contains the miniature of a French lady of the fifteenth century. She wears a head-dress of silken material, the white upper gown is bordered with fur, the under garment is yellow, and ornamented at the throat with gold embroidery. The shoes are black.

Garnaches and garde-corps. Sarraus, Garances, Cornette, Visagière

Long narrow white gowns without any ornament were worn by great ladies at home, when there was no occasion for ceremony; and they remained in fashion for a considerable length of time. There were also short sleeveless garments like the “sarreaux,” probably called “garnaches,” and short ones with half sleeves called “garde-corps.”

Peasant women wore blue gowns, beneath which was a woollen petticoat bordered with velvet. Their hats were of straw, and a becoming white guimpe encircled the face.

Hoods or “amuses” protected the head in bad weather. The chaperon or hood was much like a domino. It was made during the reign of Philippe le Bel in a peak, which fell on the nape of the neck, and was called a “cornette;” there was an opening or “visagière” for the face. As for the aumusse, made either of cloth or velvet, it resembled a pocket, and fell over on one side or other of the neck. On fine days ladies would carry their aumusse on their arm, as is done with a shawl or mantle.

Le Parement des dames

In “Le Parement des Dames,” by Oliver de la Marche, the poet and chronicler of the fifteenth century, he mentions slippers, shoes (of black leather probably), boots, hose, garters, chemises, cottes, stomachers, stay-laces, pinholders, aumônières, portable knives, mirrors, coifs, combs, ribbons, and “templettes,” so-called, because they encircled the temples and followed the edge of the coif with an undulating line.

To these we must add the “gorgerette,” gloves of chamois and of dogskin, and the hood, and we shall understand the “under” dress of a noble lady in the earlier half of the fifteenth century. With regard to the “outer” dress, we must remember that the material nearly always bore a large brocaded pattern. The paternoster or rosary put a finishing touch to the costume. These rosaries were either of coral or of gold, and were considered as ornaments taking the place of bracelets.

Notwithstanding legislative prohibitions and social distinctions, the desire of attracting attention led all women to dress alike. From this resulted a confusion of ranks absolutely incompatible with mediaeval ideas.

St. Louis forbade certain women to wear mantles, or gowns with turned-down collars, or with trains, or gold belts. He wished that both in Paris and throughout his whole kingdom the distinction of class should be defined and obvious.

Precious stones and jewellers

Afterwards, in 1420, the Parliament of Paris renewed the same prohibitions with no greater success. It is said that women of high character comforted themselves by saying: “Bonne renommée vaut mieux que ceinture dorée.” (“Fair fame is better than golden belt.”) This, whether true or not, has passed into a proverb.

A great number of jewellers existed in Paris in the fourteenth century. Yet real pearls were little known. The Government thought they had provided against every danger by forbidding the sale of coloured glass in the place of real stones. Trade with the Levant initiated us into the science of precious stones, and at first they were regarded with general reverence, supernatural virtues being attributed to them. People imagined that rubies, sapphires, and sardonyx produced certain marvellous effects.

Castles and other dwellings of the middle ages

The second period of the Middle Ages was full of artistic instincts, and beautiful castles and dwellings rose up on every side. Meanwhile, home life had become more refined in some classes of the population.

Every man who had acquired wealth, or even a modest competence only, built himself a residence according to his taste, and frequently displayed magnificence far beyond his means. Dressers, cupboards, carved chests, ivory, bronze, enamelled copper, miniature statues, reliquaries, and a quantity of other articles, hitherto unknown, were to be seen in palaces and wealthy houses, and even in humbler abodes.

But among the poor there was no such change. Their homes had remained the same for many centuries, their cottages and little enclosures of land were unaltered. These contained the barest necessaries only. Yet a marked improvement was apparent in furniture and cooking-utensils.

With greater comfort in their homes and with better furniture than in the past, both Frenchmen and Frenchwomen were making an onward progress in their mode of life and their social relations. In the towns as well as in the depth of the country, people met together of an evening to listen to a band of skilful minstrels, a sort of concert. On the eves of feasts the women sat together at their embroidery or the spinning-wheel. Long legends were narrated, to the delight of family circles, and children were made happy by little picture-books drawn expressly for their amusement, while maidens and youths would draw sweet music from their lyres. These assemblies naturally developed a taste for dress. The poet Eustache Deschamps speaks of the splendour of women’s dress, of their gold and silver chains and belts, and of the little bells with which they adorned their garments.

CHARLES V. Le Sage

REIGNED 16 YEARS. FROM 1364 TO 1380. Contemporary with Edward III. and Richard II.

He was the third king of the House of Valois, a side branch of the Capetians, and is considered one of the great kings of the French Middle Ages.

- Kingdom. He recovered from the English all their vast possessions in France, except the port-towns of Calais, Cherbourg, Brest, Bordeaux, and Bayonne. In order to defend his kingdom from Spain and Italy, he made his brother Louis (duc d’Anjou) governor of Languedoc. And in order to defend it against Germany and the Netherlands, he confirmed to his youngest brother Philippe (Philip II. 1342 – 1404, founder of the House of Burgundy) the duchy of Burgundy conferred upon him by his father.

- Burgundy. This duchy consisted of Bourgogne, Auvergne, Boulogne, and Artois. Philippe the Daring married Marguerite, only daughter of the count of Flanders-whereby he added to his duchy Flanders, Rethel in Champagne, Nivers in Nivernais, and Franche-Comté”.

- Married. Jeanne, daughter of the duc de Bourhon.

- Issue. Charles who succeeded him, Louis duc d’0rleans, and several daughters. Residences. Vincennes and the Louvre.

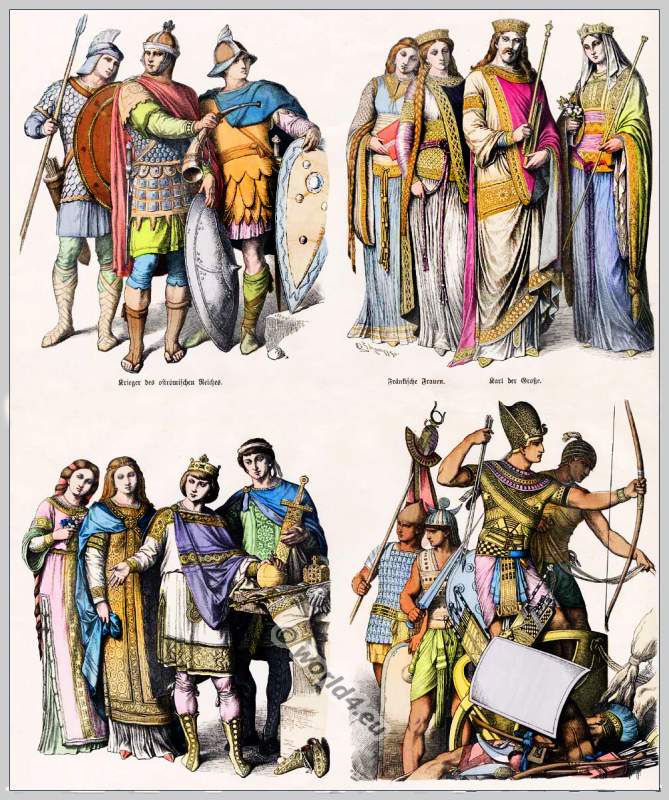

Habits and costumes. A.D 1380.

(1) Of the King. We can glean from contemporary historians and poets a pretty faithful picture of the manners and habits of the times: We know that the king rose at six, attended matins at seven, dined at eleven, attended vespers at three, and retired to bed for the night at sunset; and there is every reason to believe that these habits were in accordance with the general habits of the day.

After matins, the king gave audiences; after dinner, received his ministers; and after vespers, devoted himself to his family. He dined off one single dish, but in this was not followed by the nation. It was customary for the well-to-do to have three dishes for dinner; but the health of the king was so delicate, that he observed the greatest abstemiousness. He dressed with very great simplicity, in a long dark-coloured robe, turned up with black velvet, and confined round the waist by a cordelière,* the tassels of which fell to his feet.

Contrary to the custom of the times, he wore neither sword, dagger, nor any other distinctive mark of nobility. His only decoration being a small gold circlet of fleurs-de-lis round his black velvet cap. His hair was light-coloured, and cut square over his forehead in token of high birth. His beard was chestnut; his eyes blue; his face placid and benignant; and his whole demeanour grave, sedate, and meditative. He was very fond of dogs and hawks; and was rarely seen without two large hounds at his side, and a falcon on his wrist.

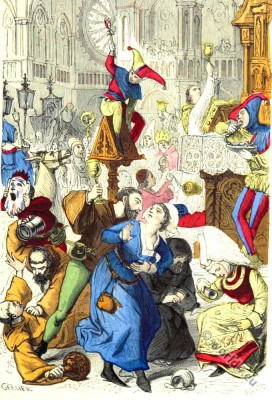

2) Of Ladies. From the Romance of the Rose we gain considerable insight into the foibles of the age. We there meet with several exhortations to both men and women which startle us, but which would have no point unless they referred to existing habits. In this allegory the poet rebukes gentlewomen for their arrogance and pride; and advises them in future to make a rule of returning a salute even from inferiors. He recommends them not to scamper about the streets; nor to turn round and stare at persons passing by; nor to stop at private windows to pry into the house; but to walk orderly and sedately along, especially when going to church.

- A Cordelière [cor-da’-le-air’] is a rope-girdle such as the Franciscans wear.

He censures them for jesting and giggling at mass; and adds, that those who can read should take their psalter with them; and those who cannot should learn the prayers by heart, that they may follow the officiating priest. The poet furthermore says, that it is becoming in a lady to be very neat in her person; to keep her nails short and clean; not to talk too loud at dinner; not to indulge in a horse-laugh; and not to grease her fingers at meals. He tells them to wipe their lips on the table-cloth, but not their nose as the custom of many is. Never to steal, nor tell wilLful falsehoods. When they visit friends not to bounce all at once into the room, but to announce their approach by a slight cough, or few words, or by shuffling of their feet, in order that they may not surprise their friends before they are prepared to receive them.

(3) Gentlemen come in for their share also of censure and advice. The poet especially ridicules peaked boots, terminating at the toes with a sharp point like a bird’s bill, and lengthened out behind to resemble a claw. As man, he says, is not a bird, why should he vainly attempt by dress to resemble that to which he bears no likeness.

The rest of the costume seems to have undergone a favourable change. Heretofore the gentry had worn long flowing robes, and hoods hanging down their backs like those of clergymen. Now both hood and robe were abandoned, especially by the younger men, who assumed instead a short jacket fitting their figure and displaying their form.

However, even at this early period the French were famous for change, and for running to extremes. Sometimes their dresses were inordinately long, at another as absurdly short; now they were extremely tight; and anon as unreasonably loose.

Institutions, Inventions, ect., in the reign of Charles V. Le Sage

- (1) The body-guard of the French kings was composed of Scotchmen. St. Louis was the first to raise this corps, which consisted of 24 men; but Charles V. increased it to 100, and called it his Cent-garde.

- (2) Besides enlarging the royal library of Paris, Charles-le-Sage had the Bible translated into French. He also reduced the number of fleurs-de-lis in the royal arms to three.

- (3) He built the royal chateau of St. Germain, although his favourite residence was the castle of Vincennes* on the banks of the Seine.

- (4) During this reign theatrical entertainments were introduced into France: The famous bastille was built by Aubriot provost of Paris, who was the first person confined there as a prisoner. Spectacles were invented. And three clocks were introduced into public buildings in France.

- This chateau was a favourite retreat of the French kings in the 12th, 13th, and 14th centuries. Philippe-Auguste inclosed it with a high wall; St. Louis administered justice there under the oak-trees of the park; Philippe de Valois demolished the old castle and commenced the new chateau, which was finished by Charles V. Le Sage. From the reign of Louis XI. it was used chiefly as a state prison.

Celebrites in the Reign of Charles V. Le Sage

Bertrand du Guesclin (1320 -1380, nicknamed “The Eagle of Brittany” or “The Black Dog of Brocéliande”) Lord High Constable of France, was certainly the most celebrated person in this reign. Not that he had any pretensions to literary merit, for he could neither write nor read, but that his victories rendered a most substantial service to his country, and constitute the chief glory of Charles surnamed the Wise.

He was twice taken prisoner; once at Auray, when the king paid the brave Chandos 5000 for his liberation; and again at Navaretto, when he himself fixed the price of his ransom at the enormous sum of 14,000. When the prince of “Wales, whose prisoner he was, asked him how a poor knight could furnish so vast a sum of money, Guesclin replied, “The spinning maidens of my country will earn my ransom with their wheels, if I can raise it in no other way.” It is said by French historians that the wife of the Black Prince, out of honour to this brave Breton, contributed half the amount of the ransom, and that the people of Brittany subscribed the rest.

After Charles V. made his treaty with England he seized upon Brittany in order to unite it to the crown, but the Bretons rose as one man to resist the annexation, and the king charged Bertrand du Guesclin with instigating the insurrection. The brave old soldier, indignant at this charge, sent his sword to the king, and threw up his office. He was of middle height, with a large head, broad shoulders, and legs bowed from being constantly on horseback. He had a vulgar, but not unpleasant face. His eyes were intelligent, and his manners urbane.

Oliver de CLISSON succeeded Guesclin as Lord High Constable, and retained that office for 12 years.

Source:

- The HISTORY OF FASHION IN FRANCE; OR, THE DRESS OF WOMEN FROM THE GALLO-ROMAN PERIOD TO THE PRESENT TIME, FROM THE FRENCH OF M. AUGUSTIN CHALLAMEL. by Mrs. CASHEL HOEY and Mr. JOHN LILLIE.

- The political, social, and literary history of France. Brought down to the middle of the year 1874. By the Rev. Dr. Cobham Brewer.

- The arts in the middle ages, and at the period of the Renaissance von Paul Lacroix. London: Chapman and Hal 1875.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.