Gardens of the Great Mughals.

CHAPTER VII

GARDENS OF THE DAL LAKE

by Constance Mary Villiers-Stuart.

I went down into the Garden of Nuts To see the green plants of the Valley, To see whether the Vine budded And the Pomegranates were in flower. "Song of Songs"

KASHMIR, the state which outweighed the whole Indian Empire in the estimation of the Emperor Jahangir, must have been particularly dear to the Mughals; reminding them as it did of their cool northern home – country. The whole country, however, is not very large, consisting of one main valley ninety miles long by twenty-five miles broad, completely encircled by high mountains, and when the Mughal Emperors visited it, the difficulties of transport and of securing provisions, as well as the actual dangers of the road over the mountain passes, made it necessary to restrict the number of the Court as far as possible.

Only nobles of the first rank were permitted to accompany the Emperor and Empress. What intrigues and heart-burnings there must have been over the question of privilege, since courtiers not in favour were condemned to stop short at the foot of the great mountains in the suffocating heat of the Bember ravine! The summer Bernier visited Kashmir, Fadai Khan, Grandmaster of the Artillery, Aurungzeb’s trusted foster-brother, was left in charge, stationed as a guard below the pass, “until the great heat be over when the King will return.”

There are three old routes into the country: by Bember and the Pir Panjal; the Jumna route by Verinag; and a much longer journey from the north-west through the valleys of the Kishenganga and Jhelum. This last seems to have been the natural outlet from Kashmir and the most frequented route in early times. At Hasan Abul, where the road leaves the plains, the Mughal Garden of Wah Bagh can still be seen. It was built here on account of the springs and used as an Imperial camping-ground.

WAH BAGH

Hasan Abul, like Bawan, Achebal, Verinag, and Pinjor, is one of those naturally beautiful spots which each religion in turn claims as a holy place. Legends of Buddhist, Brahmin, Mohammedan, and Sikh gather round the numerous springs that gush out of the ground at the north-west foot of the precipitous hill of Baba Wali.

The Chinese Buddhist pilgrim, Hwen Thsang, journeyed from Taxila to visit the spring; where he mentions the tank, fringed with lotus flowers of different colours, built by the Serpent King, Elapatra-one of those vague shadowy Naga kings whose splendours haunt all Indian history, and whose legendary doings reappear with a strange persistence in old Indian gardens.

The place is said to owe its present name to Akbar, who was so struck with its beauty, that it drew from him the exclamation of Wah Bagh ! (Oh, what a garden I) and Wah Bagh it is to this day. But it was Akbar’s son Jahangir who actually built the garden-palace.

Moorcroft *), who visited Wah nearly ninety years ago, describes it at some length: “The garden covers a space about a quarter of a mile in length, and half that in breadth, enclosed by walls partly in ruins. The gateways and turrets – that were constructed along the boundary-wall are also mostly in a ruinous condition. The eastern extremity is occupied by two large stonewalled tanks; the western by parterres, and they are divided by a building which served as a pleasure-house to the Emperor and his household. It was too small for a residence, consisting of a body and two wings, the former containing three long rooms, and the latter divided into small chambers.

The interior of the whole is stuccoed, and in the smaller apartments the walls are decorated with flowers, foliage, vases and inscriptions, in which, notwithstanding the neglected state of the building and its antiquity, the lines of the stuccoed work are as fresh as if they had but just been completed, indicating a very superior quality in the stucco of the East over the West.

The chambers in the southern front of the western wing, and others continued beyond it, constitute a suite of baths, including cold, hot, and medicated baths, and apartments for servants, for dressing, and reposing, heating rooms and reservoirs: the floors of the whole have been paved with a yellow breccia, and each chamber is surmounted by a low dome with a central sky-light.

The water, which was supplied from the reservoirs first noticed, is clear and in great abundance. It comes from several copious springs, at the base of some limestone hills in the neighbourhood and, after feeding the tanks and canals of the garden, runs off with the Dhamrai river that skirts the plain on the north and east.” The present owner takes a great interest in this old Imperial pleasure-ground, and has recently built up the ruined walls and done much to restore the gardens.

*) Travels in the Himalayan provinces of Hindustan and the Punjab: in Ladakh and Kashmir: in Peshawar, Kabul, Kunduz and Bokhara by William Moorcroft and George Trebeck, 1841.

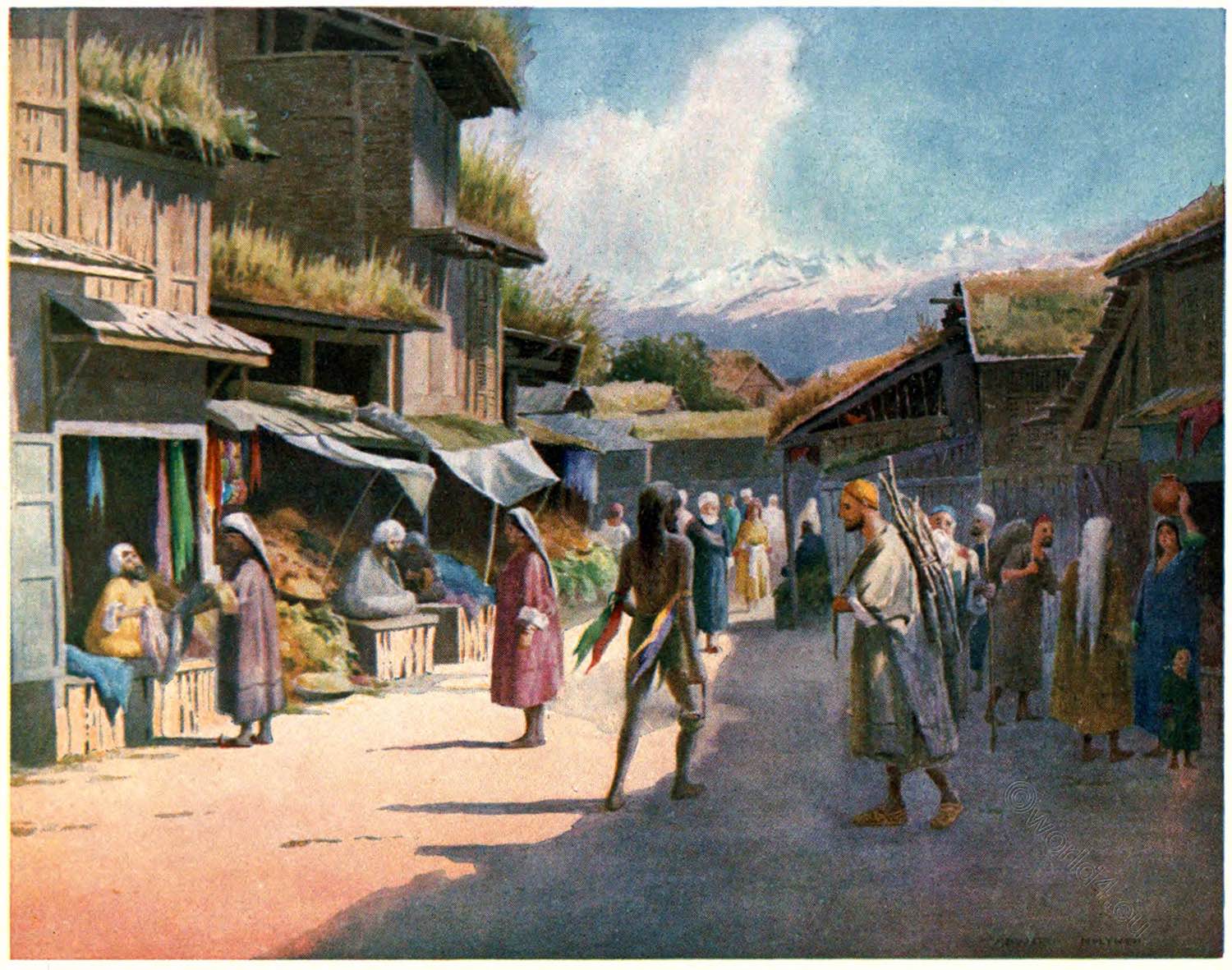

LALLA ROOKH’S GARDEN

Entering the Kashmir valley through the ravine of Baramulla, the rest of the journey to the capital at Srinagar was undertaken by water. Crossing the stormy Wular Lake, the largest lake in India, Sumbal on the Jhelum River proved a favourite halting – place. At a short distance below the village a canal leads off to the little Manasbal Lake.

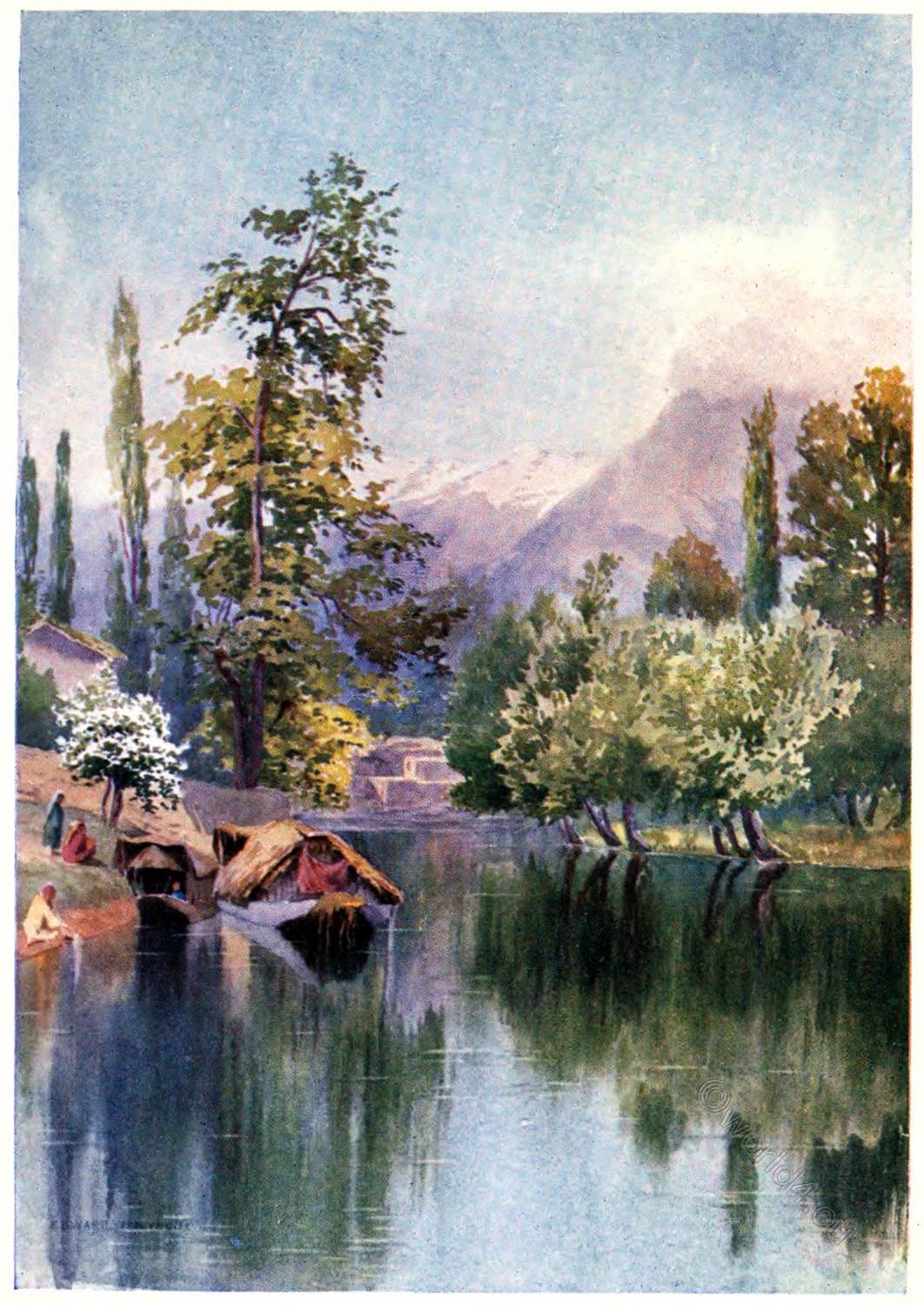

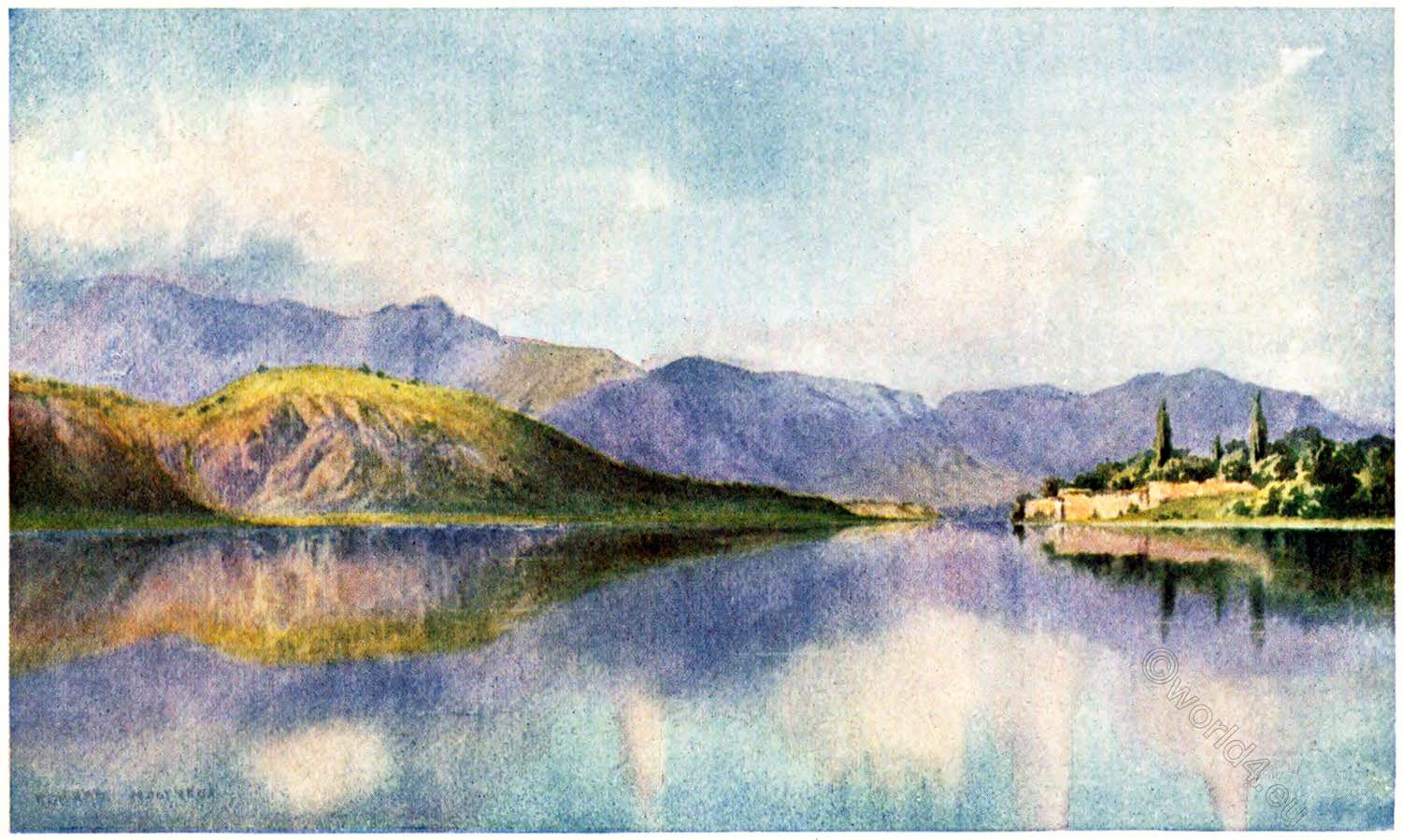

The road to Gilgit runs along its western shore, and round the steep north-eastern banks are remains of various Mughal gardens. The largest of these, the Darogha Bagh, the royal palace built for the Empress Nur-Jahan, now fancifully called Lalla Rookh’s Garden, juts out into the lake with its burden of terraced walls and slender poplar trees, like some great high-decked galleon floating on the calm clear water.

The banks of the Manasbal are deserted now, the gardens are in ruins. Only a few sportsmen, or hardy tourists, venture their boats up the narrow canal, and anchor in the shadow of the old chenars. Fashion sets away elsewhere, toward the English hill stations, with their small log huts perched high up on the mountain sides. But the Mughals, with their love of scenery and genius for garden – building, rarely chose a better site than the shores of this loveliest and loneliest of all the Kashmir lakes.

Akbar was the first Emperor to enter Kashmir. He built the fort at Srinagar called Hari Pabat (the Green Hill), and planned a large garden not far away on the shores of the Dal, that beautiful lake which lies between the city and the mountain amphitheatre to the north of Srinagar.

CHENAR TREES (Platanus orientalis)

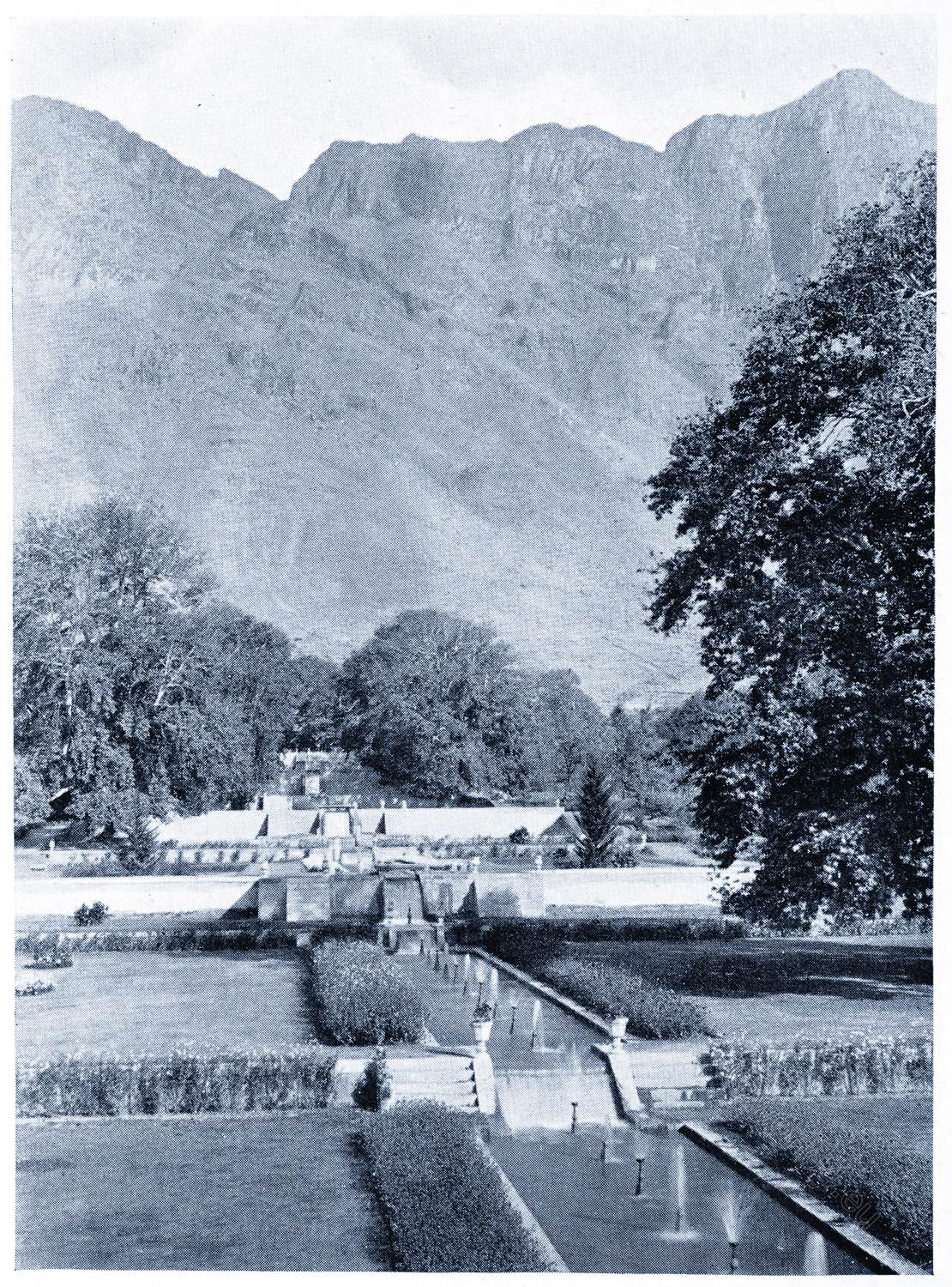

The Nisim Bagh, Akbar’s garden, stands in a fine open position well raised above the lake; and takes its name from the cool breezes that blow all day long under its trees. The walls, canals, and fountains have disappeared; and the avenues of magnificent chenars with which it is closely planted must have been added long after the garden was laid out, if ‘Ali Mardan Khan was the first to introduce these trees into the country. Fully grown they resemble heavy-foliaged sycamores with serrated leaves and smooth, silvery boles and branches.

They were, and are, greatly prized for their size and beauty, and more especially for their dense shade. Apart from the garden avenues, chenars are often to be seen in the villages and by the sides of the old caravan roads. They are usually planted at the four points of a square so as to shade a plot of ground all day long, and thus formed a series of halting-places between one camp and the next.

In Kashmir they still remain royal trees; they are Government property, not to be cut down without a special permit from the Maharaja. Green turf covers the ruined masonry terraces of the Nisim Bagh, which rise grandly from the water; but the trees are in their prime, and the view , from under their boughs across the blue expanse of the lake, crowned by the snow – streaked Mahadev, remains as enchanting as when Akbar chose this site for the first Mughal garden in Kashmir.

Between the Nisim and the Fort there is a smaller lake, at the far end of which are the remains of a picturesque garden – called the Nageen Bagh. What is left shows another lakeside garden, smaller, but in character much like that of Lalla Rookh on the Manasbal. It is built on a narrow point of land, its terraces rising on three sides out of the water which forms large canals on either hand. A pavilion shaded by great chenars stands close down by the edge of the lake.

All round the sides of the Dal Lake there are broken walls and terraces, the remains of early Mughal gardens. Hazrat Bal, the village close to the Nisim Bagh, stands on the site of one of these. The large mosque, where the hair of the Prophet is preserved, and specially venerated once a year at a great mela, is built round the principal garden-house. The narrow stone watercourse runs beneath it, and through the village square, in the midst of which a beautifully carved stone chabutra figures conspicuously and still forms a convenient praying platform. The old entrance can be seen in the long line of stone steps leading down to the water, but the most interesting feature at Hazrat Bal is the carved stone fountains.

CHABUTRA FOUNTAINS

In the early northern gardens, before the canals were enlarged sufficiently to admit of the line of fountain jets which afterwards became such a characteristic, these shallow fountain basins were used as much in the open garden as they were in rooms or verandahs.

Sometimes they were introduced in the centre of a raised stone chabutra; or placed at intervals along the narrow watercourses like those at Hazrat Bal, the finest of which we found hidden away under the wooden platform of the mosque.

This was almost lost, buried under the mud and refuse, when, thanks to the exertions of some village boys urged on by two white-bearded elders, we unearthed this really fine example of the stonemason’s art.

It is a large oval basin cut in eight deep flutes radiating from the centre; each division having a fish or wild duck carved in relief, represented as about to swim away over the edge of the fountain. A crane or stork is carved at each end where the basin is cut away to meet the swirl of the water as it rushed in and out from the narrow canal. The second fountain is similar, but smaller.

Charming as they are from a purely decorative point of view, these fountains are more noticeable on account of the birds and living creatures used in their ornamentation. This points to their early origin, when under the wise, art-loving Akbar the old Hindu temple carvers and craftsmen were encouraged to work again in stone for their new Moslem masters: and even these two forgotten carvings show that wonderful Indian sense of rhythm which still remains; a living national trait.

THE SHALIMAR BAGH

The famous Shalimar Bagh lies at the far end of the Dal Lake. According to a legend, Pravarsena II., the founder of the city of Srinagar, who reigned in Kashmir from A.D. 79 to 139, had built a villa’ on the edge of the lake, at its north-eastern corner, calling it Shalimar, which in Sanskrit is said to mean “The Abode or Hall of Love.” The king often visited a saint, named Sukarma Swami, living near Harwan, and rested in this villa on his way. In course of time the royal garden vanished, but the village that had sprung up in its neighbourhood was called Shalimar after it. The Emperor Jahangir laid out a garden on this same old site in the year 1619.

A canal, about a mile in length and twelve yards broad, runs through the marshy swamps, the willow groves, and the rice-fields that fringe the lower end of the lake, connecting the garden with the deep open water. On each side there are broad green paths overshadowed by large chenars (Platanus orientalis); and at the entrance to the canal blocks of masonry indicate the site of an old gateway. There are fragments also of the stone embankment which formerly lined the watercourse.

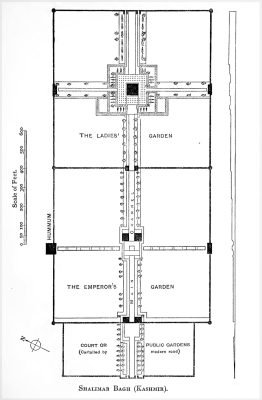

The Shalimar was a royal garden, and as it is fortunately kept up by His Highness the Maharaja of Kashmir, it still shows the charming old plan of a Mughal Imperial summer residence. The present enclosure is five hundred and ninety yards long by about two hundred and sixty-seven yards broad, divided, as was usual in royal pleasure-grounds, into three separate parts: the outer garden, the central or Emperor’s garden, and last and most beautiful of the three, the garden for the special use of the Empress and her ladies.

The outer or public garden, starting with the grand canal leading from the lake, terminates at the first large pavilion, the Diwan-i-‘Am. The small black marble throne still stands over the waterfall in the centre of the canal which flows through the building into the tank below. From time to time this garden was thrown open to the people so that they might see the Emperor – enthroned in his Hall of Public Audience.

The second garden is slightly broader, consisting of two shallow terraces with the Diwan-i-Khas (the Hall of Private Audience) in the centre. The buildings have been destroyed, but their carved stone bases are left, as well as a fine platform surrounded by fountains. On the northwest boundary of this enclosure are the royal bathrooms.

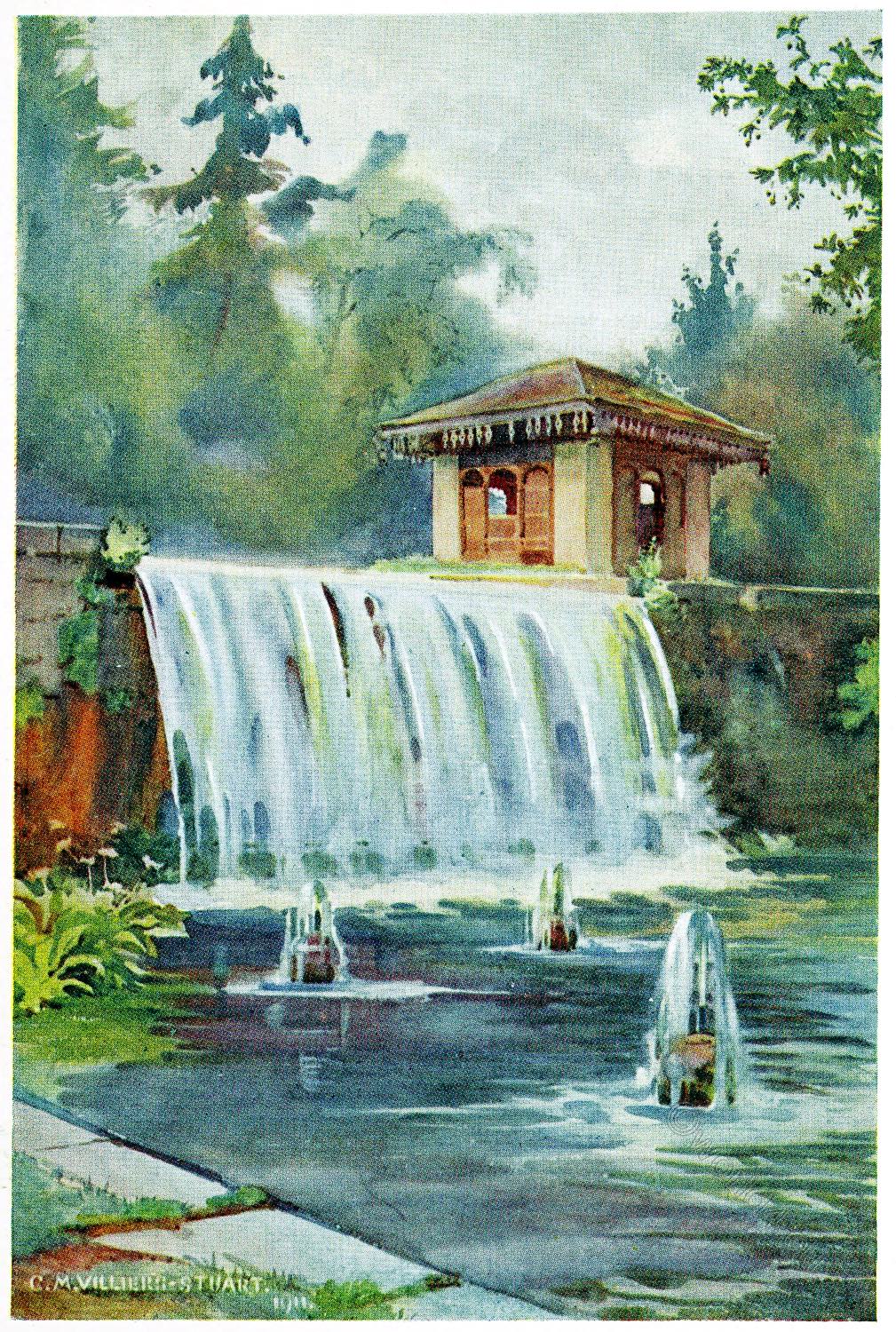

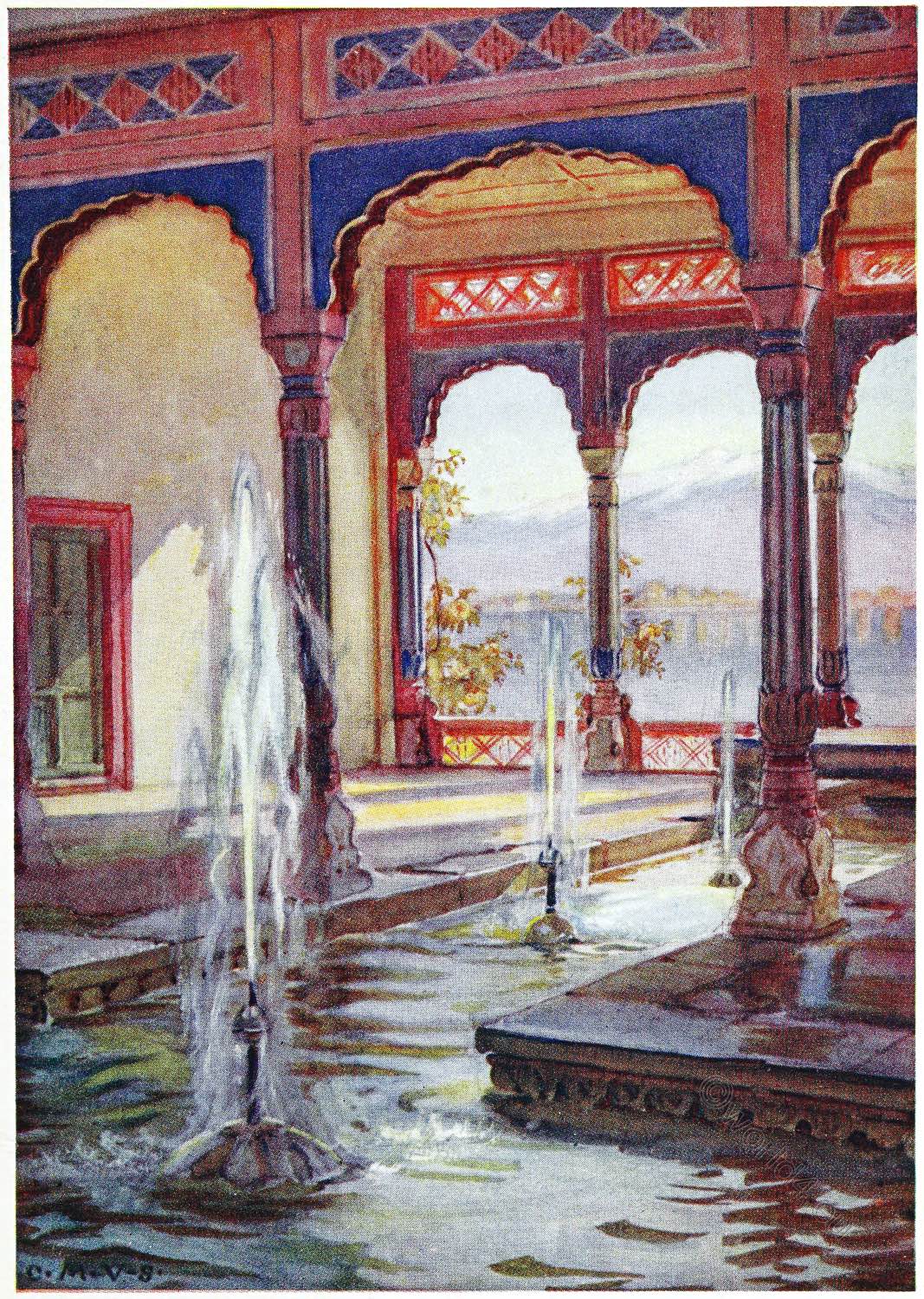

At the next wall, the little guard-rooms that flank the entrance to the ladies’ garden have been rebuilt in Kashmir style on older stone bases. Here the whole effect culminates with the beautiful black marble pavilion built by Shah Jahan, which still stands in the midst of its fountain spray; the green glitter of the water shining in the smooth, polished marble, the deep rich tone of which is repeated in the old cypress trees.

Round this baradari the whole colour and perfume of the garden is concentrated, with the snows of Mahadev for a background. How well the Mughals understood the principle that the garden, like every other work of art, should have a climax.

This unique pavilion is surrounded on every side by a series of cascades, and at night when the lamps are lighted in the little arched recesses behind the shining waterfalls, it is even more fairy-like than by day. Bernier, in his account of the Shalimar, notes with astonishment four wonderful doors in this baradari. They were composed of large stones supported by pillars, taken from some of the “Idol temples” demolished by Shah Jahan. He also mentions several circular basins or reservoirs, “out of which arise other fountains formed into a variety of shapes and figures.”

When Bernier visited Kashmir the gardens were laid out in regular trellised walks and generally surrounded by the large-leafed aspen, planted at intervals of two feet. In Vigne’s time the Bagh-i-Dilawar Khan, where the European visitors were lodged, was still planted in the usual Eastern manner, with trellis-work shading the walks along the walls, “on which were produced the finest grapes in the city.”

PERGOLAS

Pergolas were in all probability one of the oldest forms of garden decoration. A drawing of an ancient Egyptian pleasure-ground shows a large pergola surrounded by tanks in the centre of a square enclosure. The trellis-work takes the form of a temple with numerous columns. In the Roshanara Gardens at Delhi a broken pergola of square stone pillars still exists, and a more modern attempt has been made to build one outside the walls at Pinjor.

These cool shady alleys have, under European influence, entirely disappeared from the Kashmir gardens ; though here and there round the outer walls some of the old vines are left, coiled on the ground like huge brown water-snakes, or climbing the fast growing young poplars. But their restoration would be a simple matter. The pergolas with their brick and plaster pillars are a charming characteristic well worth reviving. It should be always remembered, however, to make them bold enough: high and wide with beds for spring bulbs on each side between the pillars -spring bulbs, such as Babar’s favourite tulip and narcissus, to flower gaily before the leaves of rose and vine completely shade the walks.

NISHAT BAGH

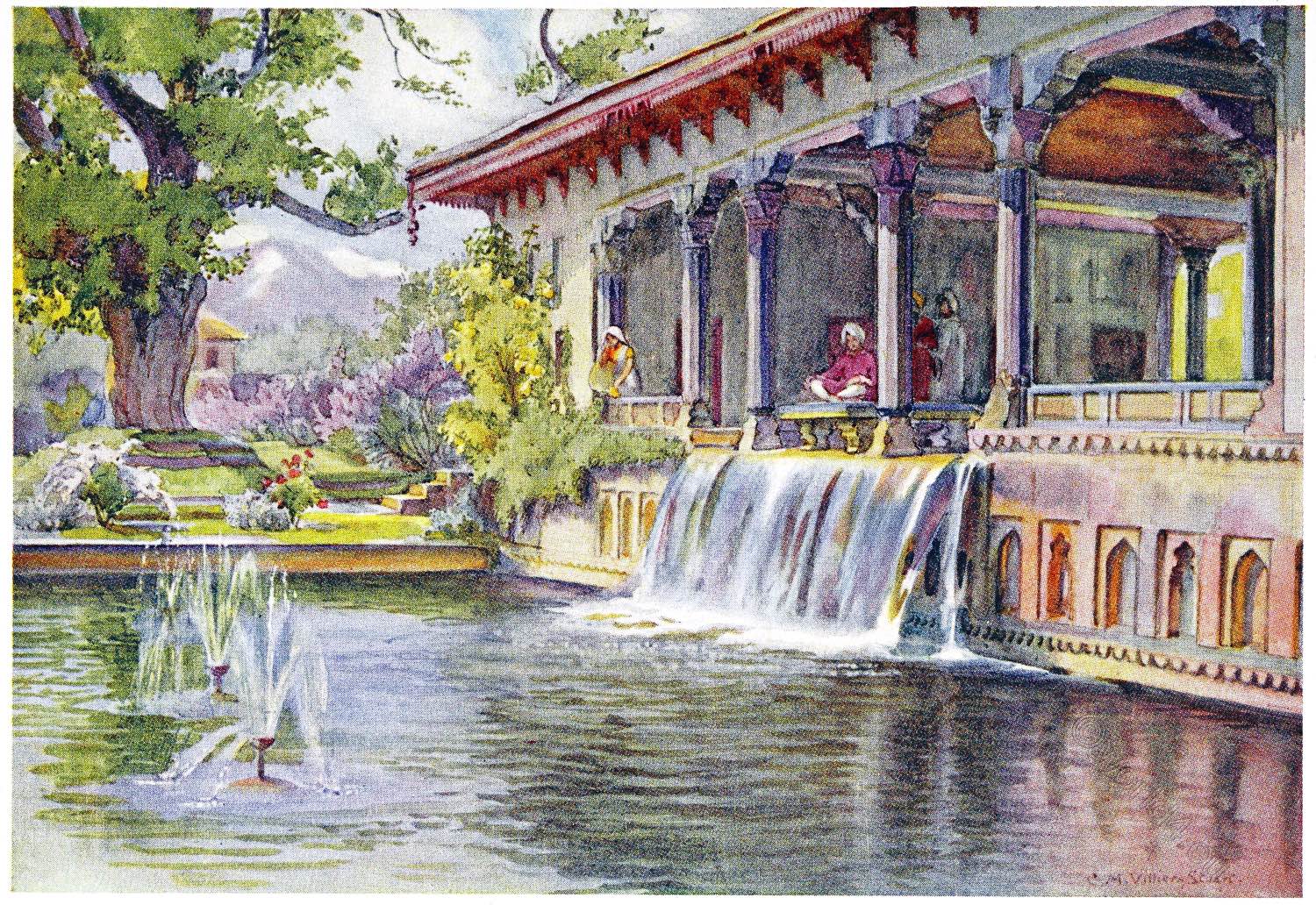

A subtle air of leisure and repose, a romantic indefinable spell, pervades the royal Shalimar: this leafy garden of dim vistas, shallow terraces, smooth sheets of falling water, and wide canals, with calm reflections broken only by the steppingstones across the stream. A complete contrast is offered by the Nishat, the equally beautiful garden on the Dal Lake built by Asaf Khan, Nur-Mahal’s brother.

The Nishat Bagh, true to its name, is the gayest of all Mughal gardens. Its twelve terraces, one for each sign of the zodiac, rise dramatically higher and higher up the mountain side from the eastern shore of the lake. The stream tears foaming down the carved cascades, fountains play in every tank and watercourse, filling the garden with their joyous life and movement. The flower-beds on these sunny terraces blaze with colour-roses, lilies, geraniums, .asters, gorgeous tall-growing zinnias, and feathery cosmos, pink and white. Beautiful at all times, when autumn lights up the poplars in clear gold and the big chenars burn red against the dark blue rocky background, there are few more brilliant, more breathlessly entrancing sights than this first view of Asaf Khan’s Garden of Gladness.

“A GARDEN OF HERBS”

“When Shah Jahan was in Kashmir in 1633, he visited this garden. Its high terraces, and wonderful views of lake and mountain, so delighted him that he at once decided that the Nishat Bagh was altogether too splendid a garden for a subject, even though that subject might happen to be his own prime-minister and father-in-law. He told Asaf Khan on three occasions how much he admired his pleasure-ground, expecting that it would be immediately offered for the royal acceptance, But if Shah Jahan coveted his neighbour’s vineyard, the Wazir was no less stiff-necked than Naboth; he could not bring himself to surrender his cherished pleasance to be “a garden of herbs” for his royal master, and he remained silent. Then as now the same stream supplied both the Royal Garden and the Nishat Bagh, which lies on the mountain side between the Shalimar and the city of Srinagar. So Shah Jahan in his anger ordered the watersupply to be cut off from the Nishat Bagh and was avenged, for the garden he envied was shorn of all its beauty.

Nothing is more desolate than one of these great enclosures when their stone-lined tanks and water channels are dry and empty. Asaf Khan, who was staying in his summer palace at the time, could do nothing, and all his household knew of his grief and bitter disappointment. One day, lost in a melancholy reverie, he at last fell fast asleep in the shade by the empty watercourse.

At length a noise aroused him; rubbing his eyes he could hardly believe what he saw, for the fountains were all playing merrily once more and the long carved water-chutes were white with foam. A faithful servant, risking his life, had defied the Emperor’s orders, and removed the obstruction from the stream. Asaf Khan rebuked him for his zeal and hastily had the stream closed again. But the news reached the Emperor in his gardens at Shalimar; whereupon he sent for the terrified servant, and, much to the surprise of the Court, instead of punishing him, bestowed a robe of honour upon him to mark his admiration for this act of devoted service; at the same time granting a sanad which gave the right to his master to draw water for the garden from the Shalimar stream.

The old approach was by water, and the Nishat Bagh, like other Kashmir gardens, loses greatly by the intrusion of the modern road, which cuts off the lake-side terrace from all the others. The enclosure is now five hundred and ninety-five yards long and three hundred and sixty wide.

Being a private garden, and not a royal pleasure-ground, there are only two large divisions: the main garden built in a series of terraces each slightly higher than the other; and the upper zenana terrace, where the wall is eighteen feet high, and runs across the full width of the garden. The water-chute running down from the second story of the small pavilion on the ladies’ terrace is constructed of paved brick arranged in the usual wave patterns, and there are traces of a similar brick pavement on each side of the canal, which at the Nishat is thirteen feet wide and eight inches deep. Each end of the high retaining wall is flanked by octagonal towers, with inner stairways leading to the upper garden.

THE MALI AND HIS “GUMALIS”

The number of stone and marble thrones is a special feature of the Nishat Bagh. There is one placed across the head of almost every waterfall. The gardens have recently been partly restored, and an attempt has been made to replace the vases which once adorned the platforms and terrace walls of all these Mughal baghs. Those already made for the Nishat are decorative and add something of the old character, but they are too small for the scale of the gardens.

The Indian mali is often laughed at for his devotion to his “gumalis” and tubs, though they are very practical in the plains, where the white ants are likely to devour everything growing in the ground,-for his crazy patchwork bedding, and his rows of untidy little pots. It is the small scale and multiplicity of these gumalis, and flower-beds, which prevents us seeing that they are only the degenerate forms. of two well-known Mughal motives-geometrical floral designs and plants in vases.

Beautiful carved stone and moulded earthenware garden vases might yet be made by Indian masons and potters if they were given scope and time. Filled with flowers, their effect on the great masonry platforms would be wonderfully fine. After all, the mali has a sound tradition in his favour.

The Nishat, like other gardens of its size, was originally planted with avenues of cypress and fruit trees. On two of the terraces green depressions mark the sites of former parterres. The garden will be even more lovely when these old details are taken into account; when roses are once more trained down the sides of the walls, and soften the edges of the steps by the water, repeating the motive of the cascades they enclose.

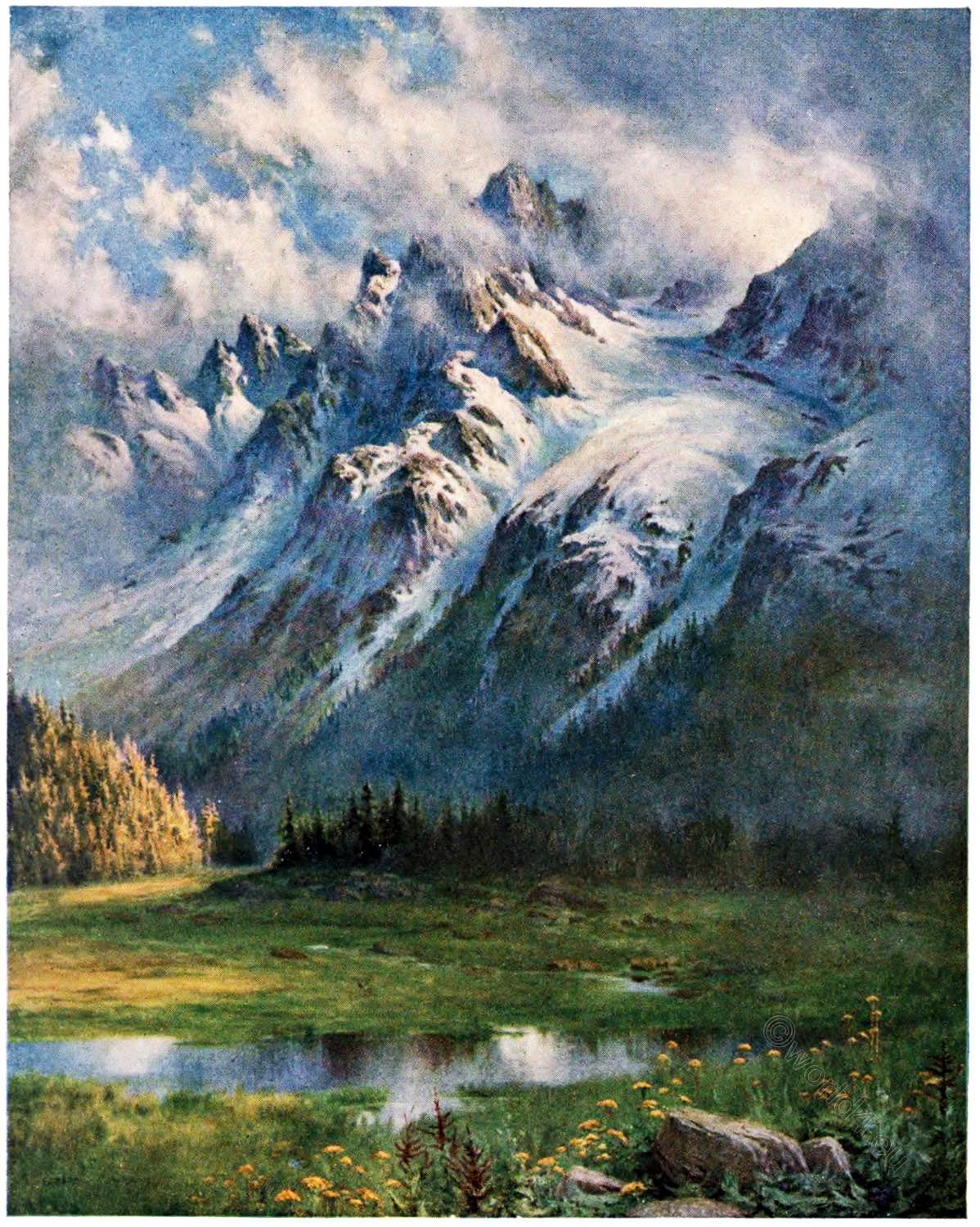

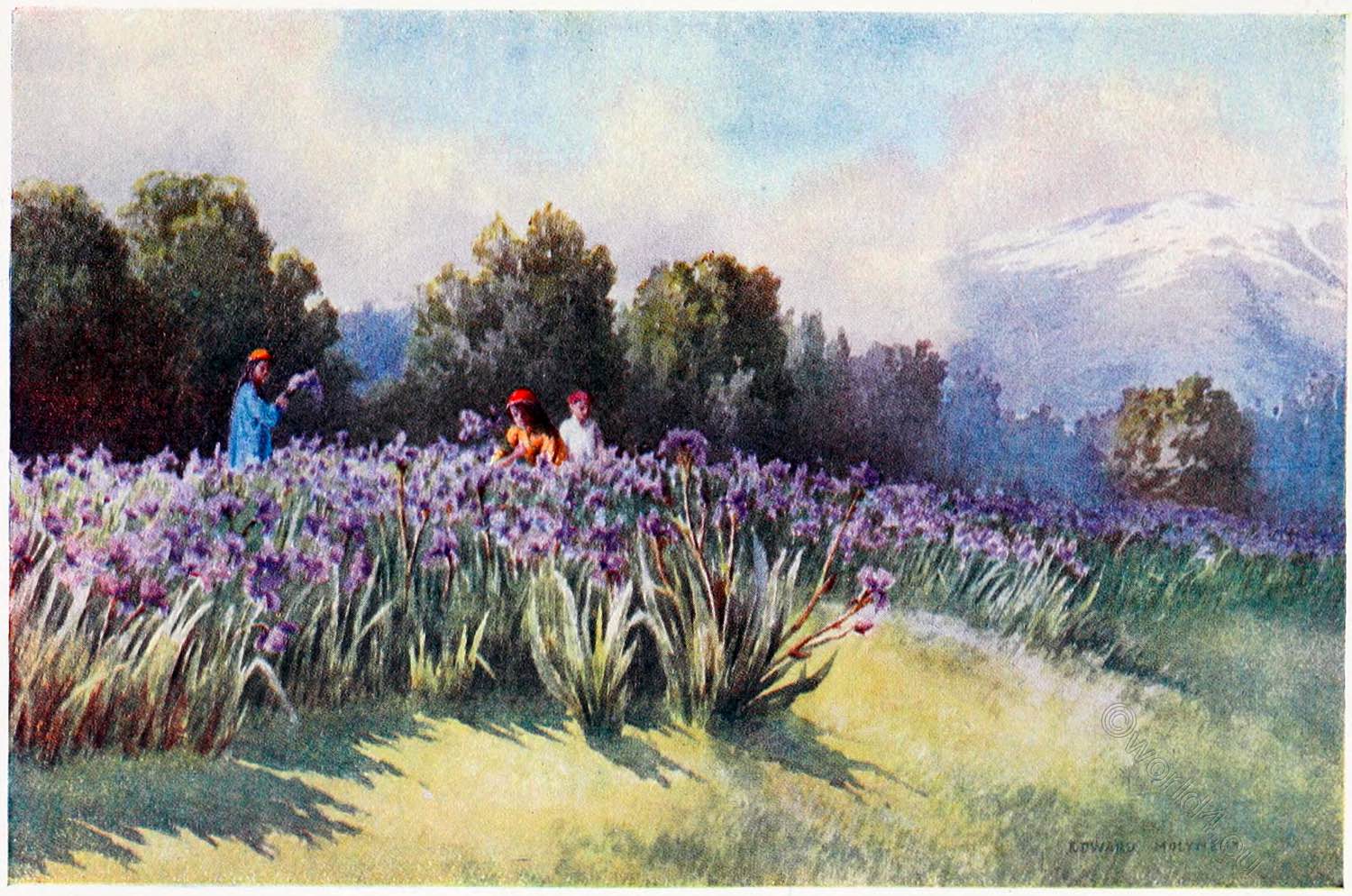

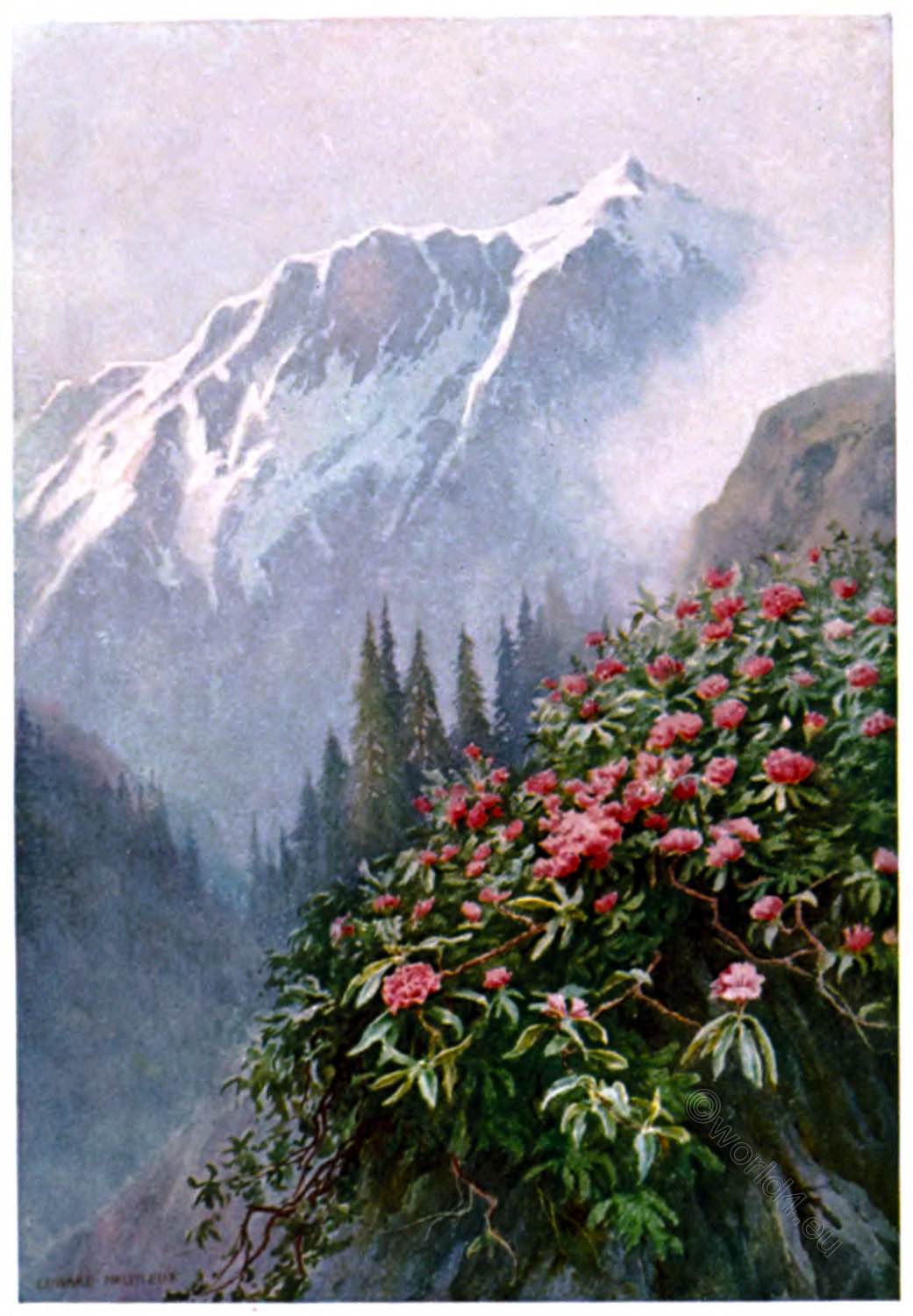

Taking a hint from the early Mughal miniatures, where the garden is “flower-scattered” like some picture by Sandro Botticelli or from the alpine meadows on the crags, which rise 4000 feet above the Nishat Bagh, let us scatter spring flowers under the fruit trees.

SPRING FLOWERS

White iris still light up distant corners of the garden with their frail beauty. But purple and mauve iris should be massed near the lilac bushes; narcissus and daffodils planted under apple and quince trees; and the soft turf under the snowy pear and plum trees should blaze again with crown-imperials and the scarlet Kashmir tulips. The Mughal flowers were spring flowers; but roses, carnations, jasmine, hollyhocks, delphiniums, peonies, and pinks brought in summer.

The baradari on the third terrace of the Nishat Bagh is a two-storied Kashmir structure standing on the stone foundations of an earlier building. The lower floor is fifty-nine feet long and forty-eight feet wide, enclosed on two sides by wooden -latticed windows. In the middle there is a reservoir about fourteen feet square and three feet deep, with five fountains, the one in the centre being the only old stone fountain left in the garden.

On a summer day there are few more attractive rooms than the fountain hall of this Kashmir garden house. The gay colours of the carved woodwork shine through the spray in delightful contrast to the dull green running water. Through a latticed arch a glimpse is caught of the brilliant garden terraces and their waterfalls flashing white against the mountain side.

Looking out over the lake which glitters below in the sunshine, the views of the valley are bounded by faint snow-capped peaks, the far country of the Pir Panjal. Climbing roses twine about the painted wooden pillars, and nod their creamy flowers through the openings of the lattice. All the long afternoon a little breeze ruffles the surface of the lake and blows in the scent of the flowers, mingling it with the drifting fountain spray; for the terrace below the pavilion is planted after the old custom with a thicket of Persian lilac.

FLOWER FESTIVALS

There are three flower festivals still observed every year in Kashmir, and the first of these is the lilac viewing. The lake-side by the gardens is crowded with boats when the long trusses of feathery mauve flowers are fully out. All day the people stream up the steps into the garden; and, sitting in rows on the terrace wall above, drink in with delight the sweet colour and scent of these favourite flowers. Nearly all the older gardens show the remains of lilac thickets; they were closely planted in squares’ divided by narrow paths through which to walk and enjoy their perfume.

The narcissus fields and tulip fields vanished -next follows the festival of the roses. The Shalimar Bagh is most frequented on this occasion. Crowds come from the city, bringing their women-folk, their babies, and their birds.

Gay family parties gather on the grass chabutras, listening to the plash of the water and the sweet little piping of the birds, or smoking their hookahs and talking endlessly in the shade. Beautiful groups they make: the women with their rose and orange robes and graceful long white veils, and the enchanting Kashmir babies, their fair faces, dark eyes, and curls peeping out from under little bright green caps, from which their large round tinsel earrings dangle.

One can hardly tell whether the babies or the flowers they are brought to look at are the prettier. Pink roses grow beside the water, red flowers fill the parterre which with its paved stone walks surrounds the zenana baradari. But the loveliest roses in the garden are the Marechal Niels, which climb the grey-green walls of the Hall of Public Audience and hang their soft yellow globes head downward in clusters from the carved cedar cornice.

It is pleasant to find what a pride and delight both Indians and Kashmiris take in the old Imperial gardens. Only the Europeanised Indians have lost touch with these simple pleasures: young Rajas, “doing” Kashmir or the gardens at Lahore, accompanied by some bored English tutor, and followed by a noisy horde of retainers, walk hurriedly up one side of the stream and down the other; but even they sometimes cast wistful glances back at the flowers and the fountains, ere they whirl off again in their motor cars.

Bustling sightseers, however, are a rare occurrence here, and the famous baghs are always full of real garden lovers. All great festivals and holidays are celebrated, if possible, in a garden.

Students bring their books, and work under the trees. A day in one of these great walled gardens is an event which appeals as much to purdah ladies as to the very poorest class. The great Emperors who planned them and lived in them-Babar, Akbar, Jahangir and his Nur-Jahan – are far more vivid personalities in India than Elizabeth or the Stuart sovereigns are in England. And every Indian speaks with a lingering regret of the days of the older Badshahi, “when the gardens were in their splendid prime.”

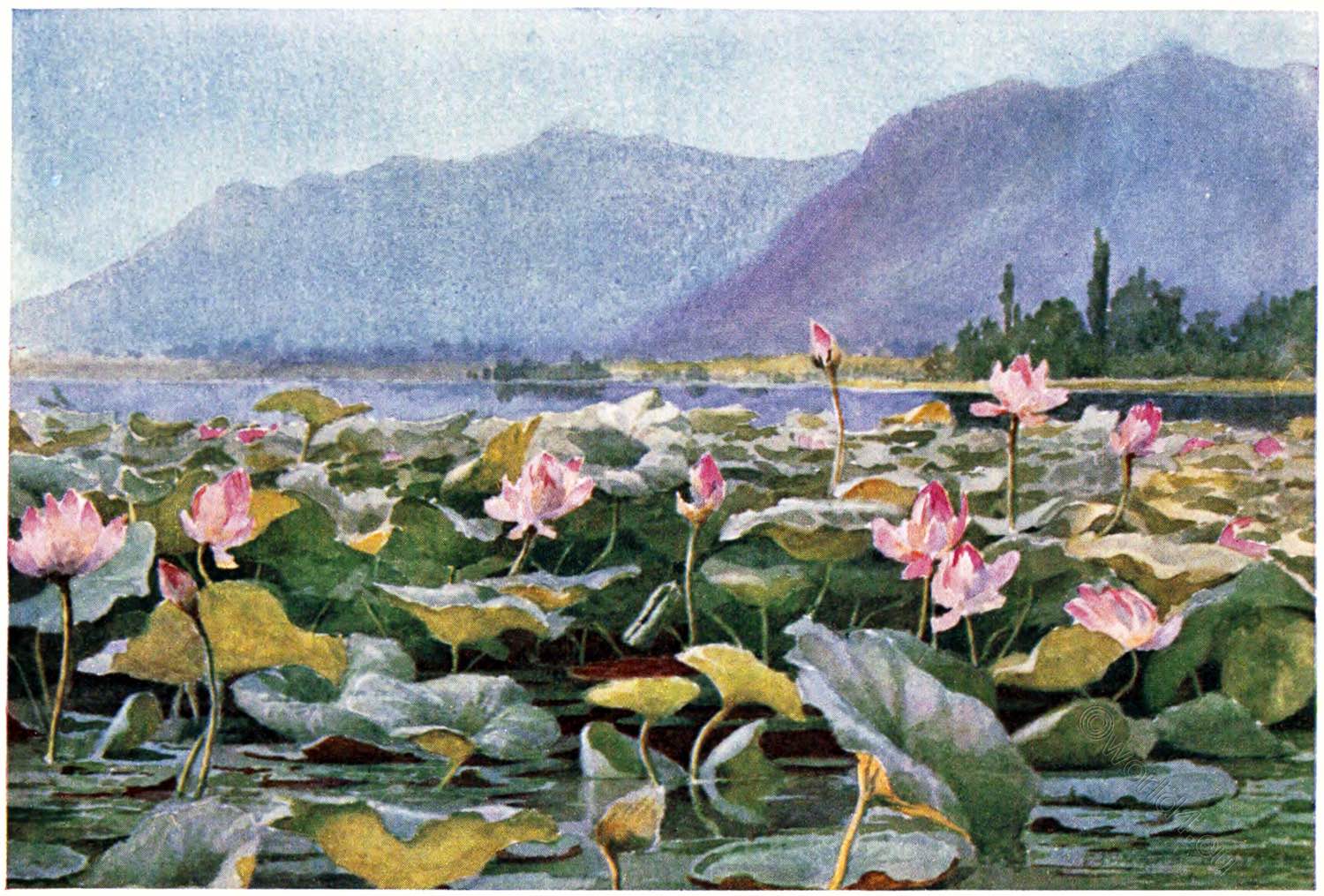

KASHMIR LOTUS FIELDS

Lotus time comes in July, when the great flowers and leaves rise on their slender stalks three or four feet from the surface of the lake. They may be taken as the Hindu sacred flower, much as the rose is the first flower in the eyes of the secular Moslem poets; and all the world goes out to gaze on the bright pink lotus blooms.

To see these flowers in perfection one must start at dawn, before the sun has climbed the mountain crags, and row out towards the Nishat Bagh, where the lake-side gardens are lost in dim blue shadows and the surface of the water is pearly grey and mauve, Then forcing the light shikara through the sweeping freshness of the large leaves until the boat is almost lost among them, wait till the sun wakes the lotus buds of Brahma.

As their rose-dyed petal tips disclose the golden heart you will know why AUM, MAN! PADME HUM (“Hail, Lord Creator! the Jewel is in the Lotus”) is the oldest and most sacred prayer in India.

High up in a hollow of the mountains which overlook the lotus fields of the Dal Lake is the Chasma Shahi, the little Garden of the Royal – Spring. Very few of these smaller pleasure grounds have survived, but the Chasma Shahi Bagh shows that a Mughal garden need not necessarily be large to prove attractive.

The enclosure, small as it is, has all the charm and shows the same Mughal feeling for sensation, as its great rivals round the lake. The copious spring round which it is built bubbles up in a large stone vase in the hall of the upper pavilion. The garden in front of this building is an oblong of about an acre divided into two terraces.

A stone chabutra with a shallow carved fountain basin, something after the fashion of those at Hazrat Bal, is the feature of the upper terrace. A tiny carved water-chute brings the narrow canal rippling down three feet to the second terrace, in the centre of which is a tank with a single fountain jet; the water running on through another pavilion at the end of the garden. These buildings are characteristic Afghan structures on older stone foundations.

Walking through the hall to the arched openings overlooking the Dal, where the wall is bounded by a black marble rail, a relic of Mughal times, the lower garden comes as a complete surprise. The narrow water-chute slopes sharply down eighteen or more feet to a second enclosure, about half the size of the upper garden. In the centre is a reservoir with five fountain jets. Round its edges are the outlines of a continuous flower parterre, and the sides of the garden are still filled with lilac and fruit trees.

There is a famous old garden saying which may be translated:

Morning in the Shadow of the Nishat Bagh, Evening in the

Breezes of the Nisim,

Shalimar and its Tulip Fields, these are the Places of

Pleasure in Kashmir and none else.

But I would add the little Chasma Shahi, with its spring, and its marvellous view, seen across the fragrant foreground of the lilac thicket.

Source:

- Gardens of the Great Mughals by Constance Mary Villiers Stuart. London: A. and C. Black, 1913.

- Kashmir by Finetta Madelina Julia Campbell Bruce. London A. and C. Black 1911.

- Kashmir by Sir Francis Edward Younghusband (1863-1942; Painted by Major Edward Molyneux. London: A. and C. Black, 1911.

Continuing

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.