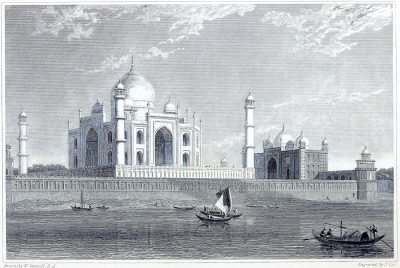

The Taj Mahal at Agra.

Whatsoever may be alleged against the character of Shah Jehan in his government of the vast empire which he partly won by his own sword, in his domestic relations, as a husband and a father, he is unimpeachable.

The mausoleum, whose incomparable beauty excites the highest degree of wonder and admiration in all who approach it, is not only a record of his taste and magnificence, but of a virtuous, holy, and undying attachment, which has been equalled by few professing a purer creed, and has been surpassed by none. The conjugal affection of Shah Jahan (Shihabuddin Muhammad Shah Jahan) for the Light of the World, as he delighted to call the lovely and pious sharer of his throne, lasted undiminished during a period of twenty years. Nor could death destroy the tie; when about to lose the object most beloved on earth, for ever, the emperor, it is said, while expressing his passionate regret, declared that he would erect a monument over her remains, excelling every other that the world could boast, in the same degree as she excelled all the daughters of the earth, If we estimate the beauty of Nour Jehan by that of her mausoleum, it must have been exquisite indeed.

The view taken of the Taj Mahal in the plate before us, is from the Jumna, which washes a wall of red granite, the boundary of the magnificent garden in which this splendid structure rises. The Taj itself stands upon a terrace or platform of white marble, the place of interment being in the centre immediately below the dome, and in this, the basement story. The steps leading to the platform occupy the front, together with the passage leading to the place of sepulture, which has no light save that afforded by the lamps which still burn above the tombs.

On the side towards the river, and the two others, are suites of apartments consisting of three rooms in each, the roofs, walls, and floors all of marble, and divided from each other by perforated marble screens; so lavishly magnificent is even the foundation of this splendid palace. Upon the platform over these apartments, a perfect square, of one hundred and ninety yards, an octagonal building surmounted by a dome, rising amidst a beautiful cluster of open cupolas and minars, arrests the eye. It is entered by four gateways, two of which are seen in the plate, the whole being of white marble, even to the latticed frames of the windows, with the exception of a beautiful mosaic work of texts from the Koran, which surrounds the gateways: these inscriptions, inlaid in black marble, form a broad and elegant border. At each corner of the terrace there is a splendid minaret of white marble, a hundred and fifty feet in height.

Notwithstanding an air of formality imparted by these slight and beautiful columns, the group altogether is without a peer; the contemplation of the chaste splendor of the material, and the exquisite felicity of the workmanship, affording never-tiring delight. The immense quantity of polished marble brought together, and the elegance of the forms in which it is disposed, give it a sort of superhuman grace; we can scarcely believe it to be the work of men, or composed of less precious materials than mother of pearl. The exceeding richness of the ornaments, and the dazzling glitter of its snowy surface, suggest the idea of pearls, or moonbeams-something, in fact, which fairies might command, but far beyond the reach of mere mortal hands.

The doors of this superb building were formerly of silver, and the lofty crescent, gleaming from a spire thirty feet high, was, with the shaft that supported it, of solid gold. Both these tempting treasures were carried away by the Jauts, and materials of less value have been substituted by the present government.

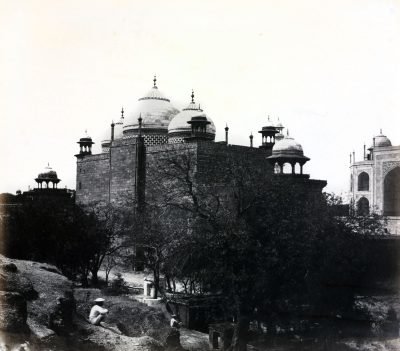

To the right and left of the Taj, upon a lower platform or terrace, are two mosques of red granite, inlaid with white marble, and crowned with marble domes, both having very high claims to admiration, and completing a group of architectural beauty, which even the splendid Moghul has rarely, if ever, surpassed.

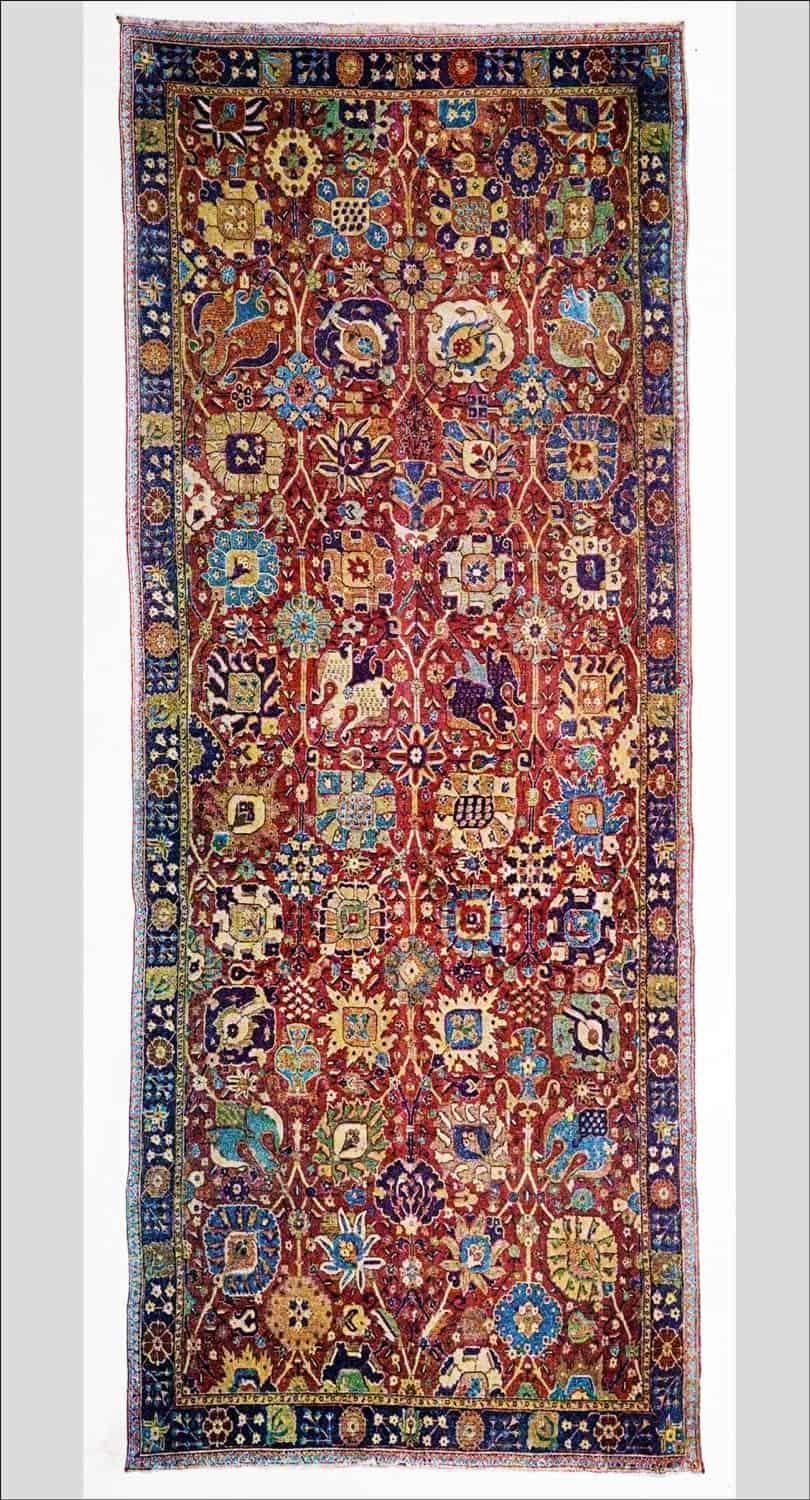

The interior of the Taj exceeds the promise given by its external magnificence: on a platform in the centre of a circular hall, are the sarcophaguses of Shah Jehan, and his beloved empress, enclosed within a carved screen of the most elaborate tracery and exquisite finish. These sarcophaguses, and the surrounding walls and screens, are covered with flowers and inscriptions of the most delicate mosaic work, in every variety of cornelian, agate, jasper, lapis lazuli, and other precious marbles. The flowers are the size of life, and so natural, that they appear as if freshly plucked and laid upon white satin: the shading is most beautifully true, five-and-thirty varieties of red cornelian occurring in a single leaf of a carnation.

The design of this building is attributed to the Emperor, but its execution was not wholly entrusted to native hands. Shah Jehan sent all over the world for skillful artists to execute his plans; and the beautiful embroideries of mosaic, for such they seem, were the works of men celebrated at Rome for their eminence in this branch of art. Round the hall containing the tombs of Shah Jehan and the peerless lady to whom this splendid shrine was raised, are several smaller apartments in the recesses formed by the octagonal shape of the building; marble-stair-cases lead to the roof, whence the view over the Jumna, and across the gardens, is one of the loveliest imaginable.

Perhaps from no other point could persons who have never visited the Taj obtain so clear a notion of this singularly beautiful edifice, as from that chosen in the present drawing, where its pearly domes and towers are mirrored in the calm waters of the Jumna, but it requires a series of pictorial illustrations to convey an adequate idea of the exceeding splendour· of a region of enchantment, which the brightest fancies of the poet or the painter have never surpassed.

On the side of the Taj opposite to the river, a large garden, too extensive for its formality to detract from its numerous beauties, luxuriant with standard peach, and other flowering trees, and celebrated for its vines and for its roses, tempers the glories of the dazzling structure beyond, by its embowering foliage and grateful shade. From the principal gateway, which forms the subject of another plate, and therefore needs no farther mention here, an avenue of cypress trees traverses the whole extent of this beautiful plantation.

It is utterly impossible for any language to convey a just idea of the impression made upon the mind by the appearance of the Taj, as it rises in virgin majesty at the end of a vista at once so beautiful, so solemn, and so appropriate. There is a melancholy sublimity about it, which touches and melts the heart; the eyes involuntarily gush out with tears, and many, who have scarcely heard the name of her who sleeps within that honored pile, approach the mausoleum weeping. The effect is heightened by basins of white marble, fed by fountains, at equal distances, which occupy the whole line down the centre of the avenue, reflecting on their glassy surfaces the elegant though mournful cypress trees, in beautiful contrast with the pearly minarets and domes mingling in the splendid picture.

In wandering about this large and ever-blooming garden, rendered an Eden by its perpetual succession of flowers and fruits, the partial glimpses obtained through openings in the trees of the clustering buildings of the Taj, its graceful minarets, and the solid grandeur of the adjacent mosques, afford a higher degree of gratification to the spectators than the more comprehensive, and also more formal view, which is generally selected by the artist, when obliged to confine his work to one point.

The Taj Mahal, which took eleven years to complete, is said to have been erected at the cost of seven hundred and fifty thousand pounds. The marble of which it is composed was conveyed by land from Kandahar, a distance of nearly six hundred miles; the granite employed in the walls of the garden, and the surrounding buildings, came from the Mewat hills in the neighborhood. Shah Jehan intended to have built a similar structure on the opposite bank of the river, for the reception of his own remains, and to have connected both by a bridge of marble; but the troubles of his reign commenced before he could put this magnificent design into execution. His declining years were spent in confinement in the fort of Agra, and at his death his corpse was interred by the side of that which he had so highly honored.

Arjumand Banu Begum (Mumtaz-Uz-Zamani, 1593-1631), the favorite wife of Shah Jehan, the Great Mogul (Emperor) of India, was the niece of the still more celebrated Nur Jahan (1577-1645), who, after the murder of her first husband, Ali Quli Istajlu, also known by his later, given name of Sher Afgan Khan, was raised to the imperial throne by Jahangir. The names by which this illustrious lady is distinguished (Nour Jehan, light of the world, Muntazi Zemani, the most exalted of the age, Moom Taza Mhal, and others) were conferred upon her in consequence of the high degree of estimation in which she was held throughout the empire. Her virtues and talents were assuredly of no mean order, and have been commemorated by testimony still more conclusive than the splendid trophy of her husband’s affection.

On the right bank of the Jumna from Agra to Delhi, there is a well at the distance of every ten or fifteen miles, made at the expense of this charitable princess, who, compassionating the sufferings of poor travelers from the dearth of water, directed that provision should be made for their comfort by a supply, which, on a journey between the two cities, she found would be very difficult of attainment by those who had not wealth at command. She was also famed for her piety, her hatred of idolatry being so great as to excite her indignation against the Portuguese, the rites and ceremonies of whose religion, savoring so much of pagan superstition, shocked her feelings, and rendered her their inveterate enemy.

The British government has with laudable zeal taken the Taj Mahal under its especial protection; more than twelve thousand pounds have been expended on its repairs, the garden is kept in perfect order, and the whole is always open to European and native visitors. The latter take a great and natural pride in this superb memorial of former power.

Upon a Sunday evening, when the fountains are playing, the garden exhibits gay groups of chewy figures, variously attired, some with caftans of velvet, or brocade, bordered with gold; others, more gaudy, shining out in tinsel finery; and a plainer description clad in white garments, bound round with flowing shawls; while the very poorest classes crowd from the neighboring city to this favorite spot, and whenever the doors of the interior are opened to an European, the native guardians not choosing to unlock them for every body, respectfully ask to be admitted in his train; a permission which is never refused.

Source: Views in India, China, and on the shores of the Red Sea by Robert Elliot and Emma Roberts. London: H. Fisher, R. Fisher & P. Jackson, 1835.