EARLY MONASTIC LIFE AND THE CONTROVERSY OVER ICONS.

Christ said to the rich young ruler, “If thou wouldst be perfect, go, sell that which thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven, and come, follow me.” (Matt, 19:21) He also said, “There are eunuchs that made themselves eunuchs for the kingdom of heaven’s sake.” (Matt» 19:12) Paul said, “to the unmarried and to widows, it is good for them if they abide even as I.” (I Cor. 7:8) Around these two conceptions all early Christian asceticism centered, and they were the foundation stones upon which monasticism built its system.

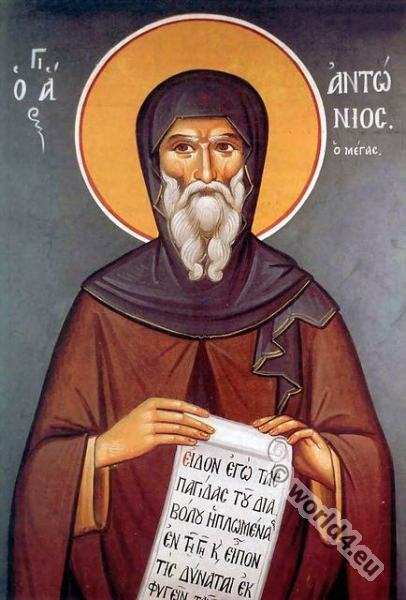

Anthony *) is considered to be the founder of Christian monasticism. He was born in Koma, central Egypt, about 250. The words of Christ to the rich young ruler impressed him to the extent of becoming a hermit. He believed himself tormented by demons in every imaginable form. He prayed and fasted constantly. By overcoming the flesh he would be drawn near to God. Anthony soon had many imitators, some whom lived absolutely alone, others in groups.

*) Anthony the Great (born 251; died 356) was a Christian Egyptian monk, ascetic and hermit. He is also called Anthony the Hermit, Anthony Eremita, Anthony Abbas and Anthony of Coma. He is often referred to as the “father of monks”.

Pachomius, born about 292, *) became a soldier and was converted from heathenism to Christianity when perhaps twenty years old. He became the first great improver of monasticism. At first he adopted the hermit life, but he became dissatisfied with the irregularities, and established the first Christian monastery in southern Egypt about 515. Here all the inmates were as a single body, having similar dress, regular hours of worship, and assigned work. At the death of Pachomius in 546, there were ten of his monasteries in Egypt. These two types, the hermit form of Anthony and the cenobite organization of Pachomius continued in Egypt, side by side.

*) Pachomios the Elder, or the Great (c. 292/298 in Latopolis, Egypt; – 9 May 348 AD in Pbow) is a Christian saint. He was an Egyptian monk and founder of the first Christian monasteries. His Coptic name Pahóm means king falcon. Traditional commemorations of him are celebrated in the Coptic and Catholic Churches on 9 May, in the Protestant and Orthodox Churches as well as by the Trappists, Cistercians and Benedictines on 15 May, and in the Armenian Church already on 28 April.

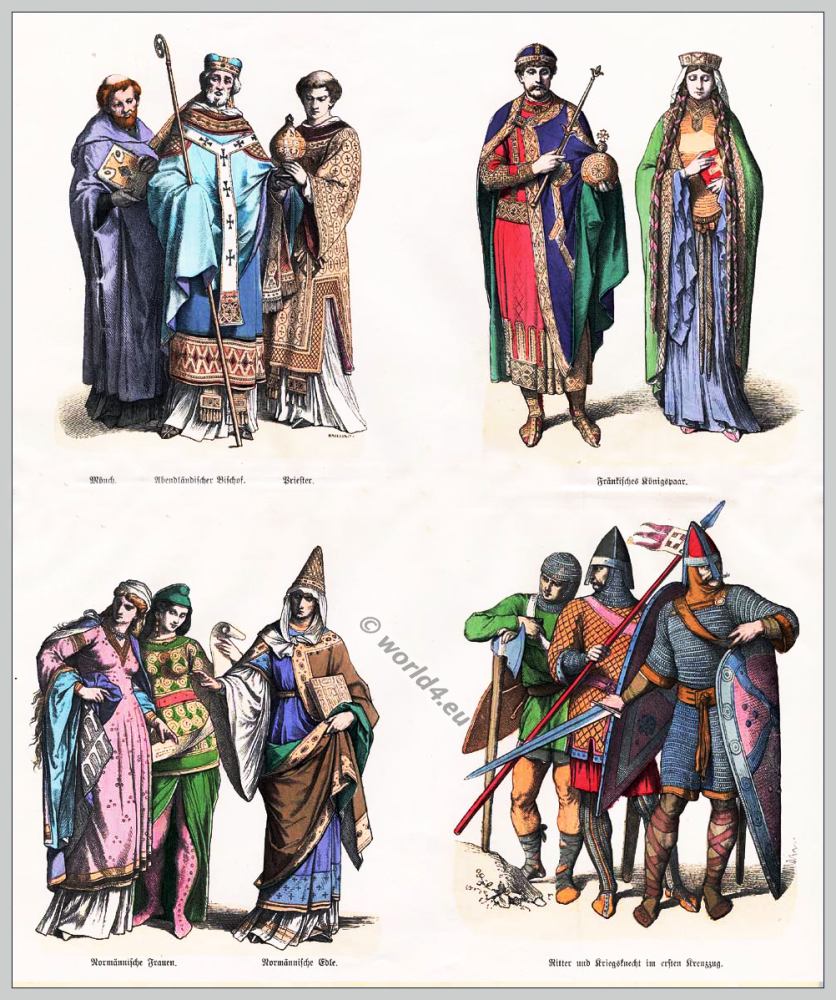

Monasticism in Syria and Palestine, continued the tradition of Pachomius, its principal leader being Basil the Great, the Bishop of Caesarea, and virtually the founder of the monastic institution in the Greek church. He determined to form an order that would conform to the inner meaning of the Bible, His rule emphasised work, prayer and Bible reading. So great is the influence of his life and teachings, that the remains still live in the Greek church.

The rule of Pachomius was carried into Italy and Gaul by Athanasius and existed in various modified form until it was supplanted by the Benedictine rule.

Montalembert, *) the brilliant champion of Christian Monasticism, speaks of monasticism as it appears in the Greek church as follows: “They yielded to all the deleterious impulses of that declining society. They have saved nothing, regenerated nothing, elevated nothing.” **) Theological discord was heightened by participation in the controversies of the time. Furious monks became armed champions of bishops, they crowded councils and forced decisions. They deposed hostile bishops or kept their favourites in power by murder and violence. It is said of the soldiers that they would rather fight the barbarians than the monks.

*) Charles-Forbes-René, comte de Montalembert (15 April 1810 in London – 13 March 1870 in Paris) was a French historian and politician.

** Count de Montalembert, “Monks of the West” Vol. 1, p. 280.

In the seventh century all the great cities of the East fell into the hands of the Mohammedans. Antioch, Jerusalem and Alexandria paid homage to this invader. This left only one city, Constantinople, that could possibly nourish a rival of the Roman church.

A dispute broke out in the eighth century between the Greek churches of the East and the Latin churches of the West. It is known in church history as the War of the Iconoclasts and was centred about the use of images in worship. This controversy was prolonged and fierce. In vain did authority forbid any kind of reverence to be paid to the images, and in vain did their destruction proceed for over one hundred years.

A party arose who declared that God had given the church over into the hands of the Mohammedans because the Christians had departed from his true worship and fallen into idolatry. These opposers of the use of images in worship were given the name of Iconoclasts (image breakers).

To the Moslems, any kind of picture, statue or representation of the human form is an abominable idol. It is known that there had existed for some time even among Christians an opposition to pictures. They held a suspicion that their use might become idolatrous. This dislike of pictures existed for many centuries before the Iconoclast persecution began.

Leo the Isaurian, who came to the throne of Constantinople in 716 A.D., was a most zealous Iconoclast. With him the real persecution commenced in A. D. 726.

He had already cruelly persecuted the Jews and Paulicians. The Christian enemies of images, especially Constantine of Nacolia, easily gained his ear. The emperor came to the conclusion that images were the chief hindrance to the conversion of Jews and Moslems, and the cause of superstition, weakness, and division in his empire. This campaign against images was part of a general reformation of the Church and State.

In 726 Leo published an edict declaring images to be idols, and commanding all such images in churches to be destroyed. Leo enforced his decree by the army.

There was a famous picture of Christ over the gate of the palace at Constantinople. The Imperial soldiers destroyed this picture, thus causing serious riot among the people. The bishop protested against the edict, and appealed to the Pope for support. The emperor disposed this bishop and appointed in his place one who would be willing to be a tool of his government.

The emperor commanded the Pope to accept the edict, to destroy images at Rome and to summon a general council to forbid their use. But Italy was too remote, so there, popes and people resisted him.

There is a story told of a priest who was delegated to carry from the Pope to the Emperor at Constantinople letters of protest against Iconoclasms. The priest was afraid to present them and came back without fulfilling his mission. He was sent a second time, and in the attempt to carry out instructions was arrested and imprisoned.

This persecution commenced by Leo the Isurian was carried on by his contemptible son, who also endeavoured to destroy monasticism. Monasteries were destroyed, monks put to death, tortured, or banished. Relics and shrines were destroyed, bodies of saints buried in churches, burned.

The most steadfast opponents of the Iconoclasts throughout the persecution were the monks and common people, partly from veneration of images, partly in the interest of freedom of the church from emperial dictation. It is true that there were some who took the side of the emperor, but as a body. Eastern monasticism was steadfastly loyal to the old custom of the church. The supporters of Icons numbered among their ranks all that was pious and venerable in the Eastern church.

After a short lull at the death of Constantino, son of Leo III, the persecution again raged in the latter years of his successor, Leo IV. Leo’s wife, Irene, had. been a steadfast image worshipper in secret. Towards the end of Leo’s reign he had a burst of fiercer Iconoclasm and was about to banish the empress when he died, in 780. With the accession of Constantine VI (780-797) the change of imperial policy came.

The Empress Irene became regent for her son Constantine VI. Fear of the army, now fanatically Iconoclast, kept her from repealing the laws at first, but she anxiously waited for an opportunity to restore the broken relation with Rome and other patriarchates.

The seventh General Council assembled in Nicaea in 787 (The Second Council of Nicaea) was attended by 577 bishops, some of whom were papal delegates. Its decree seemed to end the heresy, for monasteries were reopened and pictures and relics were restored to the churches.

Twenty-seven years after the Synod of Nicaea, Iconoclasm broke out again under Leo the Armenian, For twenty-eight years the former story was reenacted. Pictures were destroyed and their defenders fiercely persecuted. Michael II followed Leo and was succeeded in turn by his son Theophilus who died in 842.

The Iconoclastic controversy called forth a vast volume of literature. Hymnody was made a weapon of attack and defence as in the Arian quarrels. Two groups of poets, living in the seclusion of two monasteries were particularly involved in the dispute when at its height. There was the Mar Sabas group, and the second, and somewhat later, the Studium group at Constantinople. Both groups used the Greek tongues.

Source: Monastic centres of hymn writing and their influence on hymnody, by Allan Fraser.

Continuing

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.