The Hagia Sophia of Trebizond.

The Hagia Sophia (Greek Ἁγία Σοφία, “Holy Wisdom”, Turkish Ayasofya) is a large, former Byzantine monastic church in Trabzon (formerly Trebizond) in north-eastern Turkey on the Black Sea.

ST. SOPHIA.

At the western extremity of the plain, called Kapon Meidan, stands the most remarkable monument of the city of the Comneni 1), — the church of St. Sophia, the peculiar aspect of which attracts the attention of all travellers who arrive at Trebizond by sea. 2) The church stands upon an esplanade, which on the side towards the sea is sustained by substructures; the plan is that of the churches of the time of Justinian. In the centre, four white marble columns support pendentives, from which spring a dome, pierced by twelve windows: the diameter of the dome is 20 ft. 4 in. The apse has three windows, and at the extremity of each aisle is a chapel for the sacred vessels and hooks. (See Plates LX. to LXIV.)

1) The Comneni (Komnenos) were a noble dynasty in the Byzantine Empire. They provided the Byzantine emperors from 1057 to 1059 and then from 1081 to 1185, as well as the rulers in the Empire of Trapezunt from 1204 to 1461, with the title of Grand Comneni.

2) The Empire of Trapezunt was one of the successor states of the Byzantine Empire, created after the conquest of the capital Constantinople in the course of the Fourth Crusade (1202 to 1204). It extended at times over the historical lands of Paphlagonia, Pontos and the west of Colchis. The empire existed from 1204 to 1461.

The total length of the nave is 69 feet, and the width, including the aisle, 36 feet.

There is a narthex in front, the full width of the facade. The exonarthex stands out beyond this, and is entered by three archways. The gynaeonitis, or gallery for the women, extends over the narthex, hut not over the aisles. We may conclude from this circumstance, that this church is of the same date as that of the Virgin, and belongs to the same epoch.

On the north and south sides there are porches resembling the exonarthex. On all sides there are steps leading to the church.

There is no inscription recording the date of the erection of the church, but certain evidences in the internal decoration lead us to attribute its erection to the Emperor Alexis III. The interior was decorated with mosaic pictures, which were covered with a thick coat of plaster at the time it was converted into a mosque; but a part of this plastering fell down in 1836, and several figures were in this manner revealed. Between the windows of the apse were figures of stoled saints, bearing the nimbus. (See Plate LXV.)

Above one of the doors are three large figures, one representing the Emperor Alexis Comnenus III., (Byzantine emperor from 1195 to 1203) surrounded by his court: he bears in his hand the imperial orb, and his head is encircled with a diadem. The other personages are, without doubt, meant to represent the protospatharios *), the vestarius, and other chamberlains. This composition resembles in every respect the mosaic of the church of Ravenna, representing Justinian and his court; we may therefore believe that similar subjects decorated the principal churches in Byzantine times.

*) Prōtospatharios was one of the highest courtly titles of dignity in the Byzantine Empire from the 8th to the 12th century, awarded to deserving generals and civil provincial officials, but also to foreign heads of state.

The pendentives are supported by four white marble columns, the capitals of which arc cubical in form, without the dosseret. The springing of the arches is 6 ft. 8 in. above the impost.

The pavement that decorates the centre of the church is perhaps the finest specimen now in existence of Byzantine mosaic of a similar description. It consists of meanders and interlacings of precious marble, amongst which may be seen red and green porphyry, jasper, and many rare Asiatic marbles. (See Plate XVI.)

The large medallions are of marble and porphyry: upon one of them is engraved a falcon seizing a hare. Almost all the subjects in Byzantine marquetry represent animals and hunting scenes. The lateral porches are interesting, as affording subjects of study for the history of art. In the 14th century, though the Pointed style flourished in the West, it never prevailed amongst the Greeks. We cannot doubt that Pointed architecture had its origin in the East, when we find the ruins of a church of that style in one of the royal cities of Asia, bearing the date of the year 1010. The church to which we allude was built by Armenians.

But in the porches of St. Sophia we find the pointed arch appearing for the first time in a purely Byzantine building, solely, however, in an accidental manner, for it has a round arch on each side.

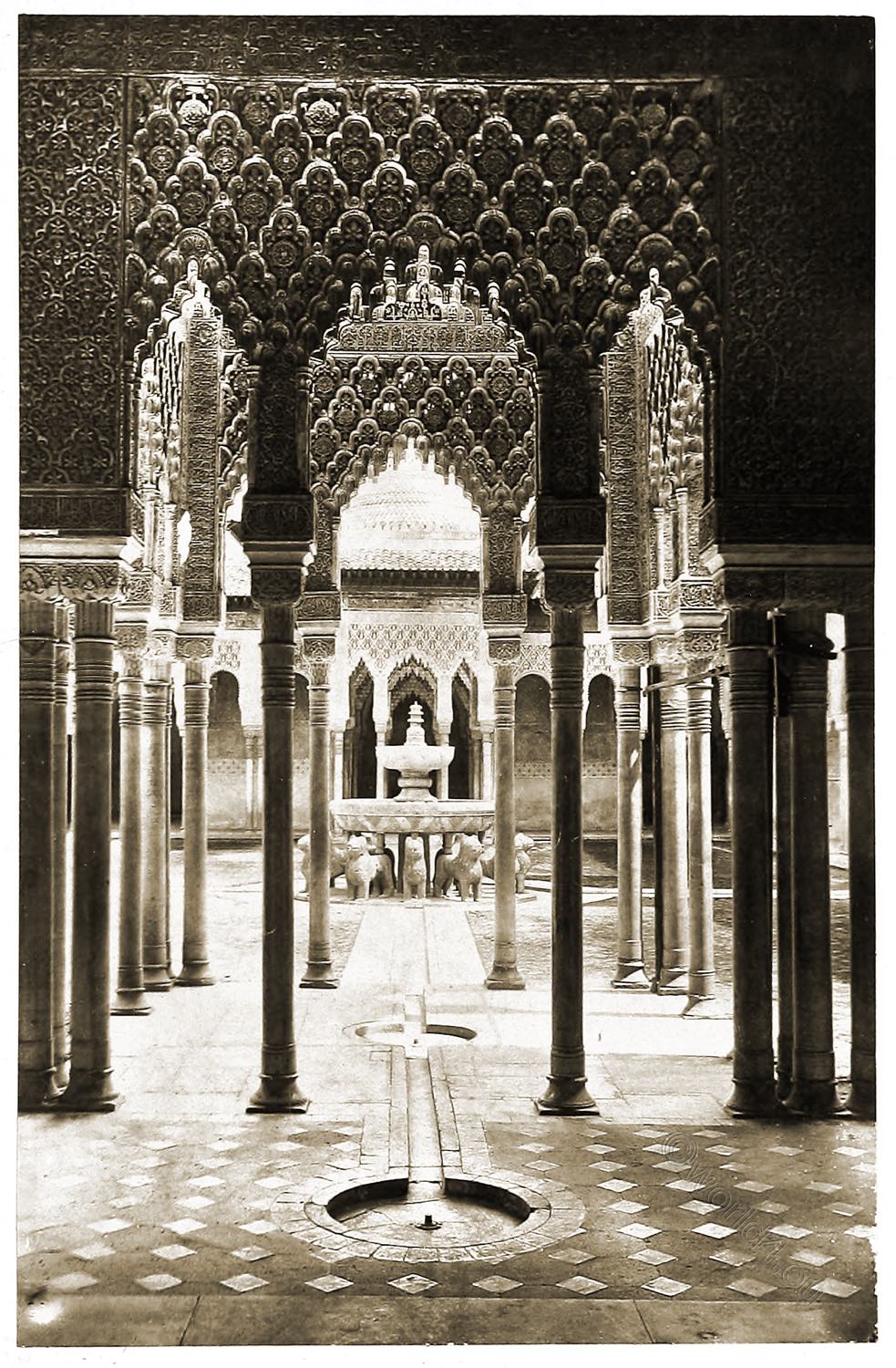

Two composite columns, 14 feet high, spring from archivolts, composed of various mouldings. The imposts show, in some degree, the influence of Arab art, as they are composed of a number of those little polygonal niches, placed one above the other, that are so common in Mohammedan ornamentation.

The tympanum of the principal arch has in the centre a quatrefoil opening, and at the sides are sculptures taken from the Old Testament. To the right we see Adam asleep; the Temptation of Eve by the Serpent on the left; Adam and Eve expelled from Paradise by the Angel. A fillet above these sculptures hears the following inscription :—

Pardon my sins.

O Lord God, have pity upon me, Lord, come to my aid. Holy, Holy.

The symbols of the Evangelists are placed at the angles, and outside the arch are the figures of two angels in the attitude of adoration.

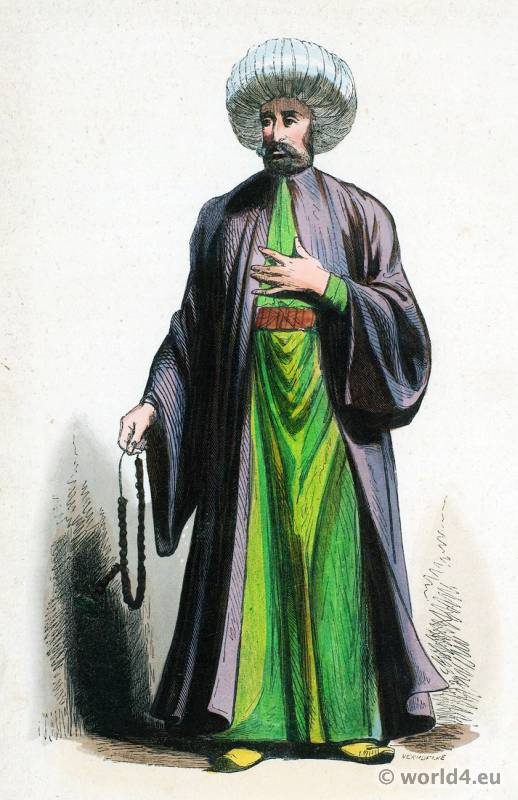

The other porch is less remarkable: we see in the niches the work of Arab artists. The Prince of Trehizond had for a long time been in alliance with the Emirs, and this fact accounts for the introduction of oriental ornamentation.

The church is built of wrought stone: it is placed on a sort of terrace, terminating in a half-circle, and upon the side nearest the sea stands an octagonal baptistry.

In front of the church stands a high square tower, resembling a hell-tower: it has an apartment in it decorated with frescoes. Fallmerayer found in it the dates 1427 and 1433.

Hamilton thus speaks of the church of St. Sophia :— “A few days after my return I visited the ruins of the Greek church of St. Sophia; we left the town by the western gate, having passed the two picturesque bridges over the ravine already described. A narrow road, between high walls and gardens, soon brought us to a green plain, called the Capu Meidân, surrounded by gardens and fields, opening to the sea on the right hand, and on the left rising up towards the hills. In front we had a distant view of the hold range of heights which terminate in Cape Yoros, the Hieron Oros of the ancients.

“The church of St. Sophia, close to the sea-shore, has been converted into a mosque by the Turks, and is in a sad state of decay. On the south side is an open porch in the Byzantine style, supported by two high slender columns, from which spring three round arches, contained within a larger one, springing from each end; a small frieze representing angels, saints, and other figures, much mutilated by the Turks, extends in a continuous line over the smaller arches. Above the centre of the large arch is a carved figure of a double-headed eagle. A similar figure is let into the outer wall at the east end of the church, which is circular, as well as the two sides. The centre is octagonal, and built in a style very superior to the rest of the building. A neat border of echinus pattern runs round it immediately below the roof, and another still more ornamental lower down.

“The walls within are stuccoed, and have been painted in fresco, but the Turks have almost entirely destroyed the paintings. The once beautiful mosaic floor is also sadly injured; but in one of the compartments I found the representation of an eagle destroying a hare. The roof is supported by four handsome marble columns. Immediately adjoining is either a belfry or baptistry, in which there have been some fresco paintings with Greek inscriptions, stating whom they represented, and when and by whom they were executed, hut so much injured that I could not make out the artist’s name, or the date of any one of them.”

Plates:

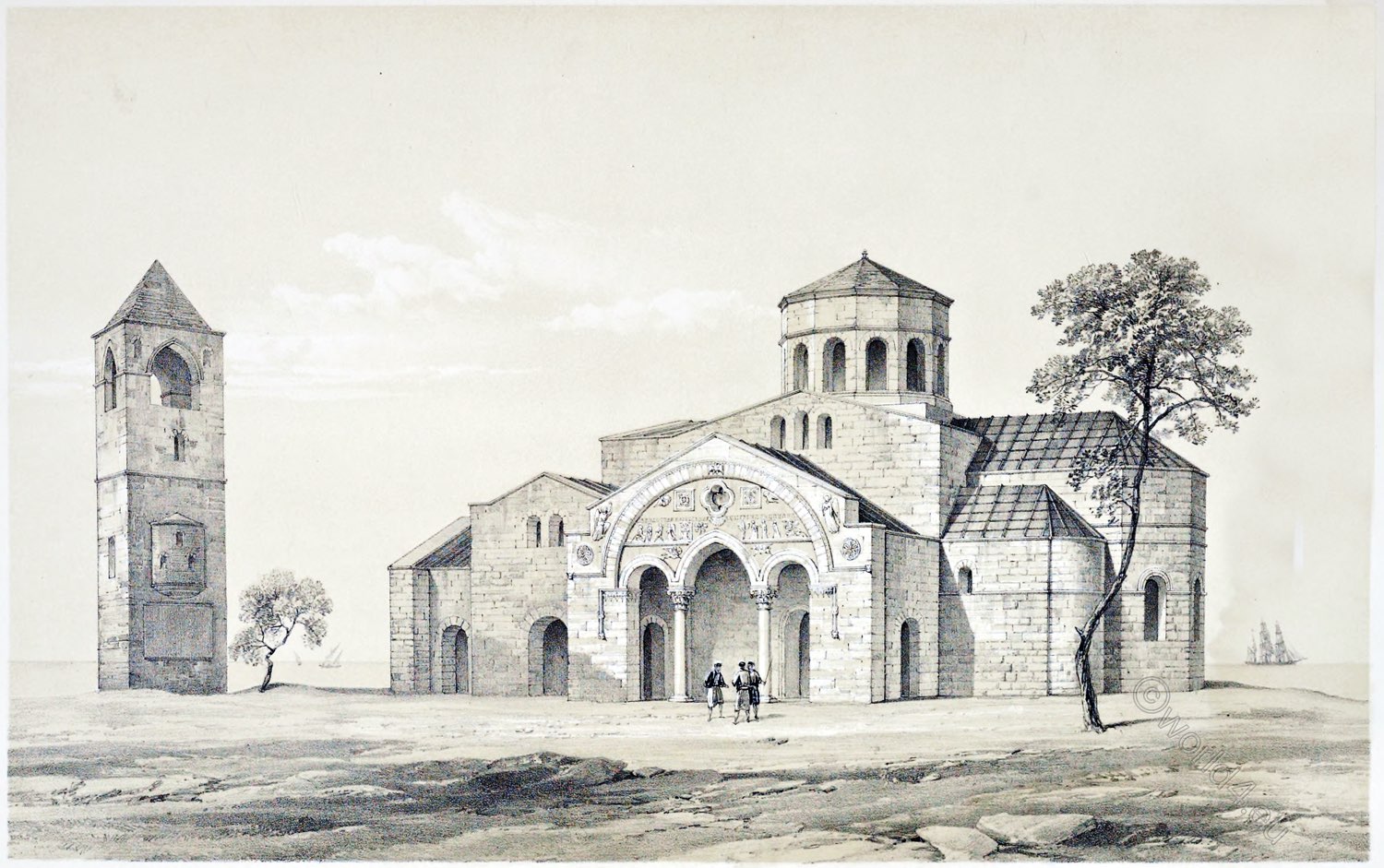

Plate LXI.

VIEW OF THE CHURCH OP ST. SOPHIA, TREBIZOND.

This building, erected by the Comneni, is situated upon an esplanade which overlooks the Black Sea, and is visible to all those who arrive at Trebizond by sea. The existence of a bell-tower, which we see to the right, shows that this church is the most modern of those we have described, being of the final period of Byzantine architecture, when the pointed arch first made its appearance in buildings of that style.

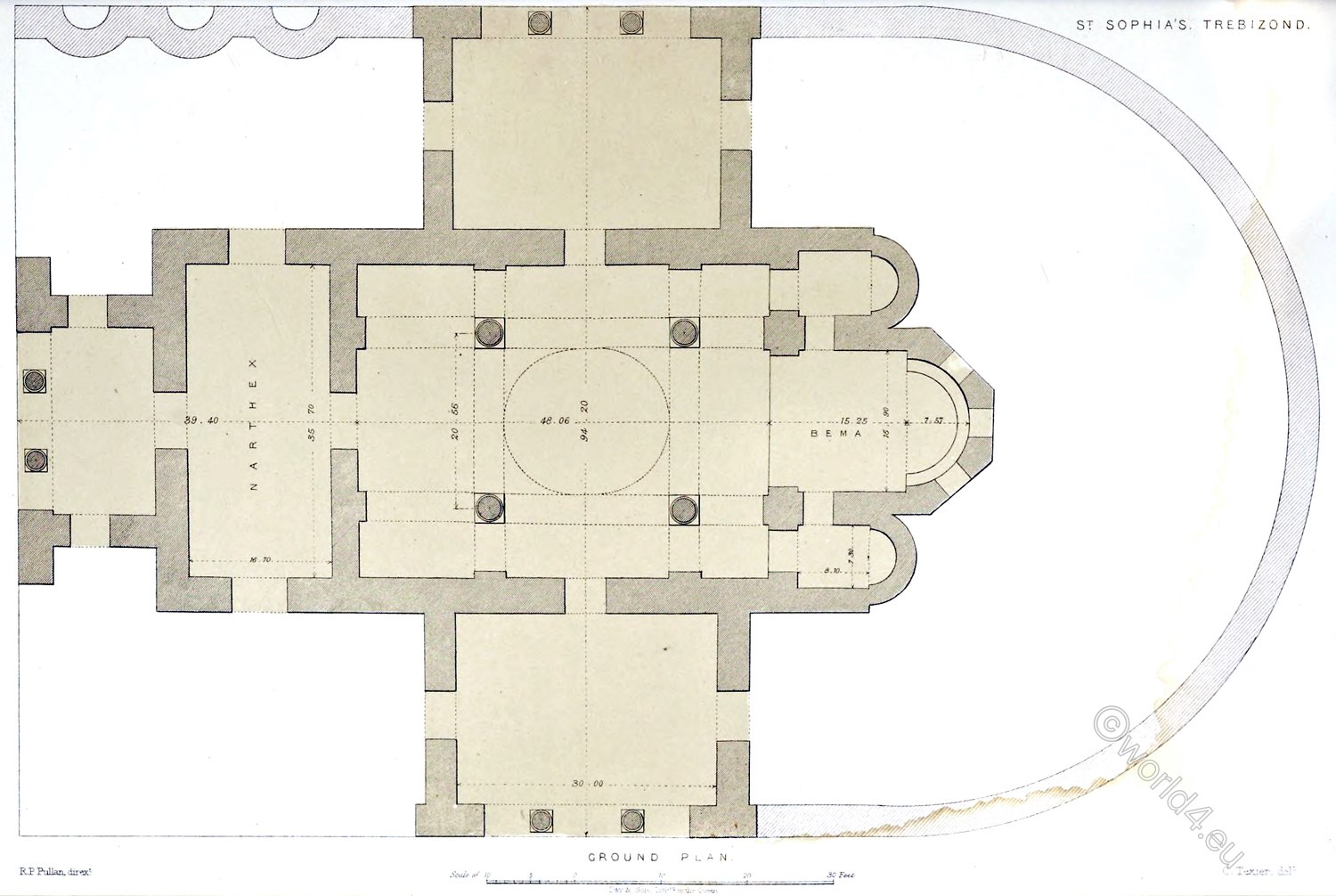

Plate LXII.

CHURCH OF ST. SOPHIA, TREBIZOND — GROUND PLAN — SOUTH ELEVATION – LONGITUDINAL SECTION.

The extensive platform upon which the church stands is cut in the side of a high plateau. It is supported on the north side by solid foundations. On the same side, a little lower down, stands an octagonal baptistry.

The plan is remarkable for a certain degree of simplicity and uniformity, which we do not find in other earlier edifices.

In the centre of this church, between the four columns, is the inlaid pavement, which we give in Plate XVI.

The section shows the same simplicity which we perceive in the plan. The church owed its chief decoration to painting.

The south elevation exhibits a mixture of the pointed and round arch, which indicates a period of transition.

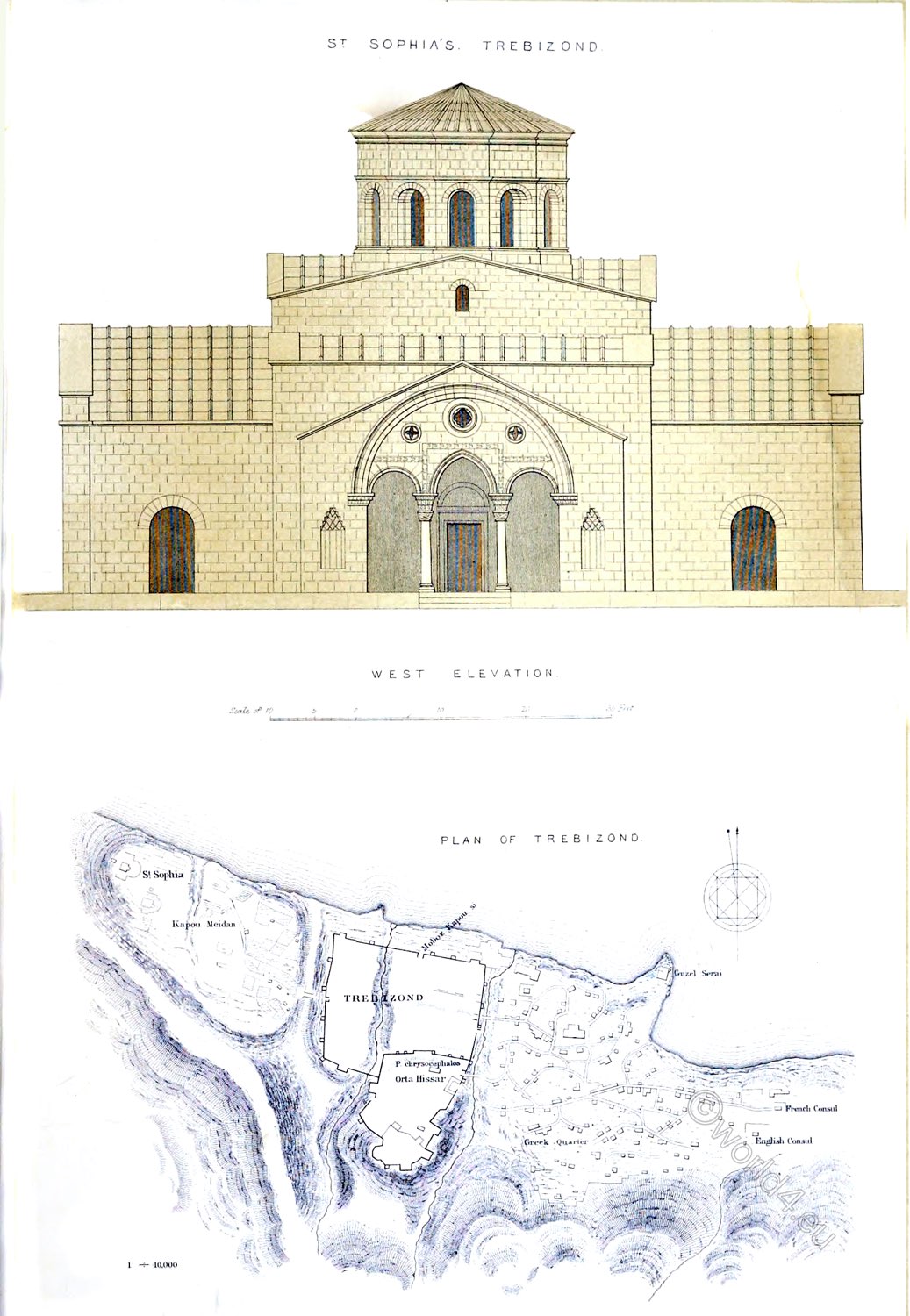

Plate LXIII.

CHURCH OF ST. SOPHIA, TREBIZOND — WEST ELEVATION — PLAN OF TREBIZOND.

The principal elevation has certain Saracenic details, which, as they do not seem to be recent, are evidences of some intercourse between the Christians and the Mohammedans. For a description of the plan of Trebizond see p. 197.

Plate LXIV.

CHURCH OF ST. SOPHIA — DETAILS OP SCULPTURE.

The tympanum of the south porch has a bas-relief representing subjects from the Old Testament. This is another innovation in Byzantine art; for up to this period paintings only were used.

The subjects are— the Creation of Woman and the Expulsion from Paradise.

To the right and left of the porch there are two figures of angels with scrolls. The church is built entirely of ashlar, and is still in a good state of preservation.

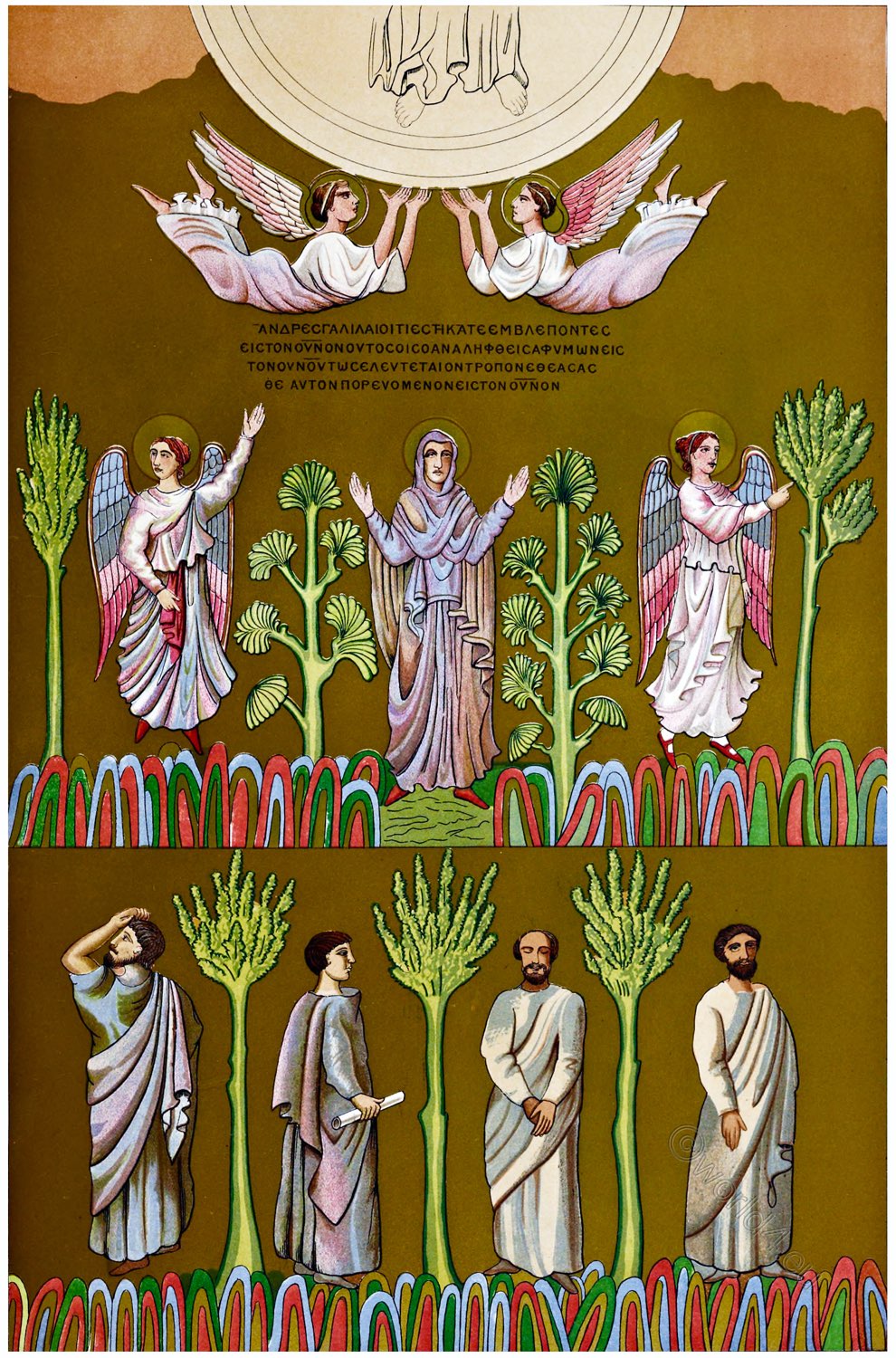

Plate LXV.

CHURCH OF ST. SOPHIA, TREBIZOND — FRESCO IN THE APSE.

Ecclesiastical decorative paintings were made the subjects of general rules, so that we find almost always the same subjects in the same parts of churches.

For instance, figures of the Apostles were generally painted on the piers dividing the windows of the choir. Here these figures are in a good state of preservation. According to the legends, the two figures on the sides are those of St. Philip and St. James. The legend of the central figure has been effaced; but it was probably the name of St. Paul.

There are many other vestiges of paintings in the church which offer interesting subjects of study.

Plate LXVI.

FRESCOES IN A MONASTERY NEAR TREBIZOND.

Fresco of Comneni (Alexios III) at Panagia Theoskepastos (“Agia Theotokos”) monastery, near Trebizond

We have given an explanation of these interesting paintings in the body of the work. We must state that these figures are not placed close together, but at some distance apart. We have also restored the draperies, instead of showing them in their actual state, blackened by the smoke of tapers.

We have also given the inscription at length. It may be remarked that there are one or two slight errors in the inscription on the plate, arising out of the similarity of the letters; for instance, A is put in the place of A, and C in the place of E.