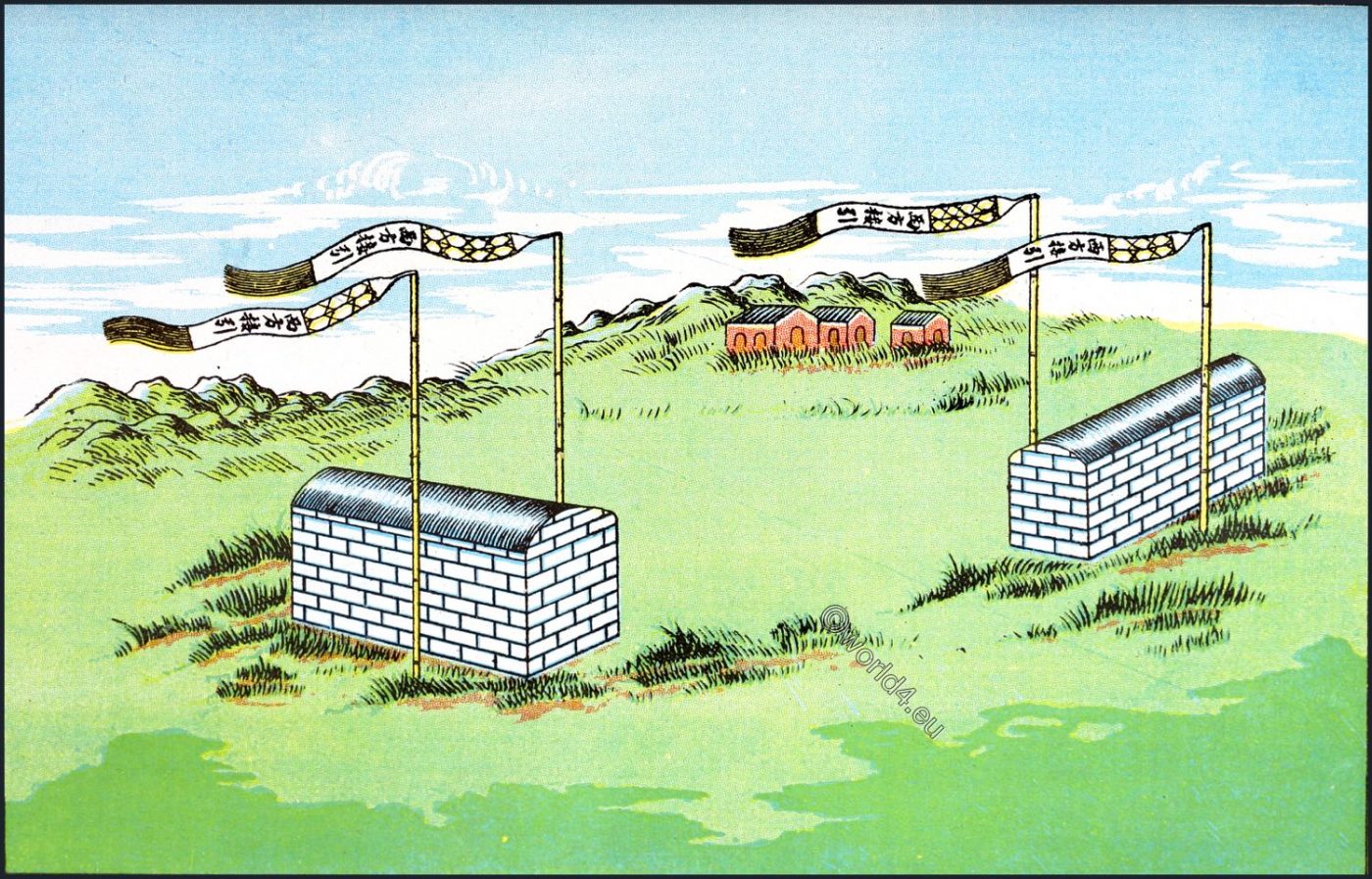

Paper streamers (Fan-tze) attached to tall bamboos on graves act as markers for souls in Buddhist belief, guiding them to their tombs. This practice evolved from ancient customs of using flags for identification. Contrarily, Confucian texts suggest the soul innately knows its resting place, unlike Buddhism’s wandering souls needing flags for direction, an idea criticized by citing the higher intellect of humans compared to birds and the rightful afterlife of virtuous individuals separate from tyrants.

Paper Streamers placed on graves. Chi-fan-tze

by Henri Doré.

In ancient times, a small flag was erected beside the grave, in order to distinguish it from others by means of this special mark.

At the present day, many persons place a bamboo on the housetop. Buddhists teach that the departed soul, wandering in space, uses this as a landmark to discover its tomb. It is for this reason that a tall bamboo is chosen, to the extremity of which is attached a streamer, Fan-tze, fluttering in the air.

The ancients set up a flag beside the grave, in order to indicate its ownership and distinguish it from others, while at the same time the name of the deceased was written on a board placed in front of the coffin.

Nowadays, people believe in the teaching of the Buddhist priests, who assert that the departed soul wanders in space, and cannot find out its resting-place; a high pole is, therefore, set up and a streamer attached to the extremity of it. The streamer bears the name of the deceased, who, thanks to this device, is enabled to find out his way.

Buddhists hold that the soul after death, either goes to the Western Paradise 2), or it must pass through the eighteen departments of Hell, or return to the world of the living through the process of the metempsychosis.

2) A latter-day substitution for Nirvana, a philosophical conception too abstruse for the popular imagination. This so-called happy land is ruled by Amitabha and the Bodhisattvas, Kwan-yin and Ta Shih-chi (the Indian Mahasthamaprapta), the “three Holy Ones” of Buddhism.

Now, here we find these same people teaching: that the soul wanders in space, without knowing where to go to; that it even requires to see its name written on a strip of cloth, in order to find out its dwelling-place. Is not all this sell contradictory?

In the work entitled “the Great Learning” Ta-hsioh the poet says: “the twittering yellow bird (a species of oriole) rests on a corner of the mound”. Confucius said: “when it rests, it knows where to rest. Is it possible that a man should not be equal to this bird”? This means that every being knows its proper resting place.

This yellow bird, which is so tiny among the feathered tribe, Hits in the air, and has no need of a landmark to fly to the corner of the mound, where it chooses to alight.

If really the soul of man, as Buddhism teaches, wanders in space and cannot find out its grave, without seeing” this guiding flag, then we must admit that man’s soul is less intelligent than the little yellow bird. Formerly, a distinguished Chinese grandee said in eulogizing the Emperor Yao: “he has ascended beyond the fleecy clouds, and dwells in the happy land of rulers”.

The Book of Odes, Shi-ta-ya says: “Wen Wang is on high; the wise kings and the three sovereigns are in heaven”. The place where the good are rewarded, cannot be the same as that where the wicked are punished.

Tyrants like Kieh 1), and Chow 2), wicked men like Tao-chi 3), cannot by any means live together with Yao and Wen Wang, and dwell in the blissful abode of rulers. Such are the principal arguments whereby Chinese writers refute the above Buddhist doctrine. Our great Worthies dwell in a happy land, the realm of rulers, whence tyrants are excluded. Therefore souls do not wander in space as Buddhists assert.

1) Kieh-kwei, the last ruler of the Hsia dynasty. Voluptuous, cruel and extravagant, he became an object of hatred to his people, and was compelled to flee to Nan ch’ao (in the present province of Ngan-hwei), where he died B.C. 1766. Mayers. Chinese Reader’s Manual.

2) Chow-sin the abandoned tyrant, who closed the Shang dynasty. Among his vices, were extravagance and unbridled lust. Defeated by Wu Wang, he fled to a tower, set it on fire, and perished miserably in the flames. Mayers. Ibid.

3) A leader of thieves; a sort of Robin Hood in early Chinese history.

Source: Recherches sur les superstitions en Chine par Henri Doré. Le Panthéon Chinois, Zi-Ka-Wei 1916.