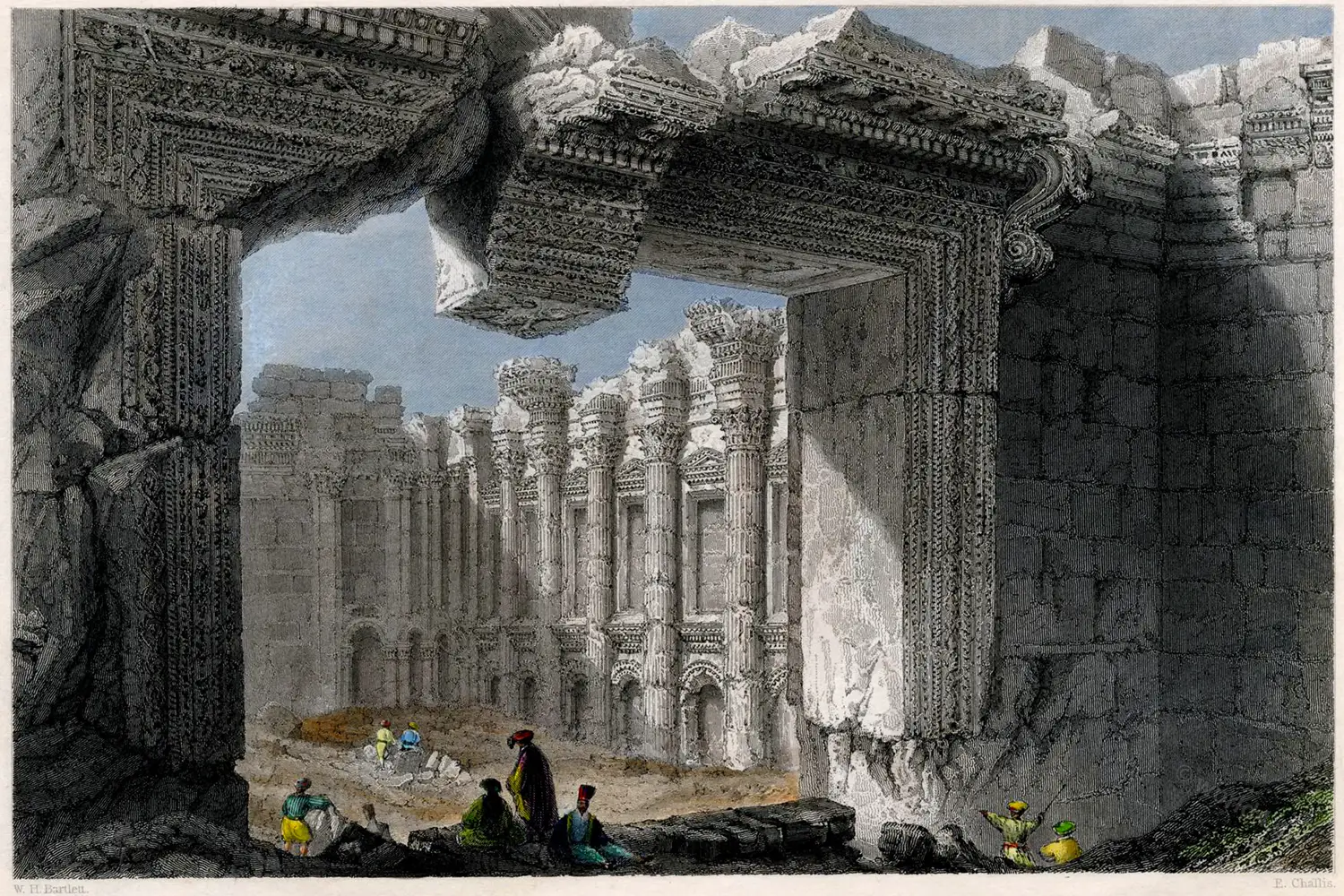

INTERIOR OF ST. PETER’S.

ROME.

"Imperial splendour all the dome adorns;

These towers a monarch built to God, and graced

With golden pomp the vast circumference;

With gold the beams he covered, that within

The light might emulate the rays of morn.

Beneath the glittering ceiling, pillars stood

Of Parian stone, in fourfold ranks disposed:

Each curving arch with glass of various dye

Was decked."

Passio Beat. Apost.

ROME is the chief object of the traveller’s attention who visits Italy, and St. Peter’s the most splendid monument of religion and art in that immortal city. Although it is uniformly the first scene of inquisitive examination, it would probably prove more conducive to the instruction and gratification of the tourist, if the study of its glories were postponed to the latest moment. The overwhelming majesty of this temple of Christianity, so completely eclipses the best efforts of modern art exhibited in the numerous churches of Rome, and throws even the temple of Capitoline Jove so wholly into shadow, that satiety of beauty, genius, and extravagance renders the merits of minor productions insipid.

As if it were designed to heighten first impressions by contrast, the visitor enters the grand colonnade, the chef-d’oeuvre of Bernini’s dramatic style, through the meanest suburb of the city. This vast oval piazza seems as a proscenium to the colossal peristyle of the sumptuous temple of St. Peter; the double colonnade is of Travertine marble, light, simple, and elegant in character.

In the centre rises an obelisk of red granite, imitated from the Egyptian pillars imported by Caligula, elevated in its present position by Domenico Fontana, and more than once celebrated in the verses of Tasso. Two majestic fountains throw up their pearly waters almost as high as the pyramidal obelisk, presenting brilliant rainbows in the splendour of mid-day, and sheets of white and dazzling foam under the influence of moonlight.

It is said, that the first view of St. Peter’s is uniformly accompanied by a feeling of disappointment; a feeling, however, which is seldom confessed, from the regret that it is not otherwise, as well as from respect for the universal judgment of the world of art.

But this sensation very rapidly subsides; and universal judgment of the world of art. But this sensation very rapidly subsides; and scarcely has the idea of pleasure arisen, when farther examination leads to unqualified admiration, and ultimately closes with rapturous astonishment. Modern Italian architecture is so entirely associated with the erection of St. Peter’s, that their histories are identical. This description of the chief basilic of Europe must, therefore, be limited to the details of the building as they exist, rather than be extended to the men and the means engaged in producing such a wonder of art.

Begun in 1502 by Bramante, the building was continued by Giuliano, San Gallo, Giacondo, Raphael, Peruzzi, and Michael Angelo, and finished, in the seventeenth century, by Carlo Maderno (1556-1629). In the portico, near to the staircase of the Vatican, are, the equestrian statues of Constantine, by Bernini, an exaggerated work, and of Charlemagne, by Cornacchini, a performance unworthy of such a place.

Opposite the principal entrance is the famous mosaic called “The Boat of St.Peter,” by Giotto, and his pupil Cavillini. The middle valves are adorned with basso-relieves of our Saviour, the Virgin Mary, St. Peter and St. Paul, separated by smaller basso-relieves representing the conference of Eugene IV. and the Emperor Paleologus relative to the union of the Latin and Greek churches.

The former are relics of ancient Rome, and represent mythological groups, amongst which may be distinguished Jupiter and Leda, the Rape of Ganymede, nymphs, satyrs, and other devices equally inappropriate for the entrance of a Christian temple.

Equal disappointment attends the first view of the interior; the justness of the proportions producing only the impression of fitness; so that no dimension startles by exaggeration, or disturbs the harmony of the whole.

Frequent and future inspection of each part in detail, soon corrects this error of inexperience, and restores to the imagination all that enthusiasm with which it approached this grand sanctuary. Familiar with its aisles, the visitor wanders on through their immensity, and enjoys a peculiar light, too brilliant to be religious, but piercing a temperature of unequalled softness: for, an agreeable vapour, of unvarying mildness, is observed to float for ever beneath these airy domes.

Nor does the resemblance to a covered city cease with the comparison of its avenues and climate; here, also, is an immense population, variously employed — peasants, loaded with their baggage, are prostrate on the marble pavement, before altars resplendent with gold and precious stones; penitents appear in converse with some venerable father at the confessional: confraternities are arranged in order; monks, whose special duty it is, take their stations at the altars; while the solemn chant of the priests performing high mass in the choir, the pealing of the organ, or slow chiming of the great bell, fall on the ear.

There are moments of solitariness and desertion, when not a whisper breaks the deep silence of the scene; then the rays of the declining sun penetrate the recesses of the sanctuary, illuminating some exquisite mosaic, hitherto wrapped in shade, and passed unnoticed, or discovering some artist so enslaved by his ruling passion that he had long forgotten he was alone.

Beneath the dome, the cross over which is elevated 450 feet above the pavement, stands the high altar. It consists of a grand canopy, supported by four bronze pillars, 120 feet in height. But, to judge of the magnitude and design of StPeter’s, and todo justice to the genius and the memory of Michael Angelo, the cupola must be visited, and the interior viewed from thence.

In accomplishing the ascent, the immensity of the structure discovers itself; for in the summit of the temple a population of workmen is found, who are continually employed in executing repairs. The bronze ball is capable of containing sixteen persons, and the prospect thence over the City, Campagna, Appenines, and the sea, is clear and magnificent.

On the interior entablature of the dome, in letters six feet high, is inscribed the glorious promise made to the first apostle — “Tu es Petrus, et super hanc petram aedificabo ecclesiam meam, et tibi dabo claves regni caelorum.” (You are Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church, and to you I will give the keys of the kingdom of heaven.)

The objects of curiosity, admiration, and instruction that have been accumulated within this sanctuary are infinite in number, of extraordinary value, and the most conspicuous merit Rich marbles compose the pavements and line the walls; admirable paintings adorn its cupolas ; bronze ornaments enrich its altars and balustrades; gilding decorates its panelled vaults, and mosaics rise one above the other in brilliant succession upon its dome; sheets ot gold overlay the most elaborate workmanship; diamonds, agates, chrysolites, and every species of precious stones, encircle the most celebrated productions of sculpture and painting, and by their multiplied and brilliant reflections literally dazzle the spectator.

In this mausoleum of princes and pontiffs the statuary art is displayed in all its powers. The bronze statue of St. Peter is a work of the fifth century; it retains its primitive merit, with the exception of an imperfection in one of the feet, occasioned by the frequent kisses of devotees. When Pope Pius VI. was in captivity, he committed to Canova the execution of his monument, and prescribed the place where his remains were to be deposited.

The effigy of the pontiff, kneeling on his tomb, is universally admired, as well as the simplicity, grandeur, and expression of the design. Next after the baldachin of St. Peter and St. Paul, the pulpit of St Peter (also by Bernini) is the most considerable work in bronze. The four doctors of the Greek and Latin churches support the apostle’s pulpit, every part of which is adorned with some device or allegory; the elaborateness of the whole has been objected to by critics.

Michael Angelo’s design for the tomb of Paul III. is the finest mausoleum in StPeter’s. It consists of a group, in which Justice and Prudence are in attendance on the little hunch-backed pope; these deities have secured the admiration of Europe, although the most accomplished artists consider that they are both inferior to the figure of Paul.

There is an enormous basso-relievo of Attila and his Page at the altar of St. Leo, which attracts attention without being entitled to it; but the ancient tomb of Innocent III. deserves a larger share of admiration than it has yet received. Here the sorrows, the caprices, and the vanities of princes are recorded by tombs of the most costly and distinguished materials. The exiled Stuarts found rest only beneath the dome of St. Peter’s; where the philosophic Christina directed also her form to be commemorated, and opposite her tomb is that of the generous and high-hearted Countess Matilda.

A modern production, the monument of Rezzonio, is probably the most popular in this boundless collection. An aged man, in the attitude of prayer, is attended by two lions: the roaring lion is allegorical of the pontiff’s firmness in refusing to abolish Jesuitism; the sleeping lion represents firmness and meekness united. The group was first uncovered on the Wednesday before Easter, 1795, under the glare of the great cross of fire that illuminated St Peter’s during the festival.

Amongst the valuable relics, gifts, and ornaments that enrich and embellish the sanctuary, is a magnificent ciborium, of lapis-lazuli, in the form of a diminutive temple, and imitated from the circular model at St. Peter’s in Pontorio, a chef d’Euvre of Bramante’s.

Source: The Rhine, Italy, and Greece in a series of drawings from nature by George Newenham (1790?-1877). London: Fisher 1841.