Lady Hester Lucy Stanhope (Chevening, Kent, England; 12 March 1776 – Joun, Lebanon, 23 June 1839) was an eccentric English aristocrat, antiquarian, and one of the most famous travellers of her age. She ruled over a local “empire” in the Druze Mountains of Lebanon.

She was proclaimed Queen of Palmyra by some Bedouin tribes before becoming a kind of prophetess among the Druze communities and in Lebanon. Her archaeological excavation of Ashkelon in 1815 is considered the first to use modern archaeological principles. She was also an intrepid traveller and explorer at a time when women were not allowed to be adventurous.

The Revue des Deux Mondes, in 1845, described her as “Queen of Tadmor, sorceress, prophetess, patriarch, Arab chieftain, who died in 1839 as a impoverished hermit under the roof of her ramshackle and ruined palace in Djîhoun, Lebanon”.

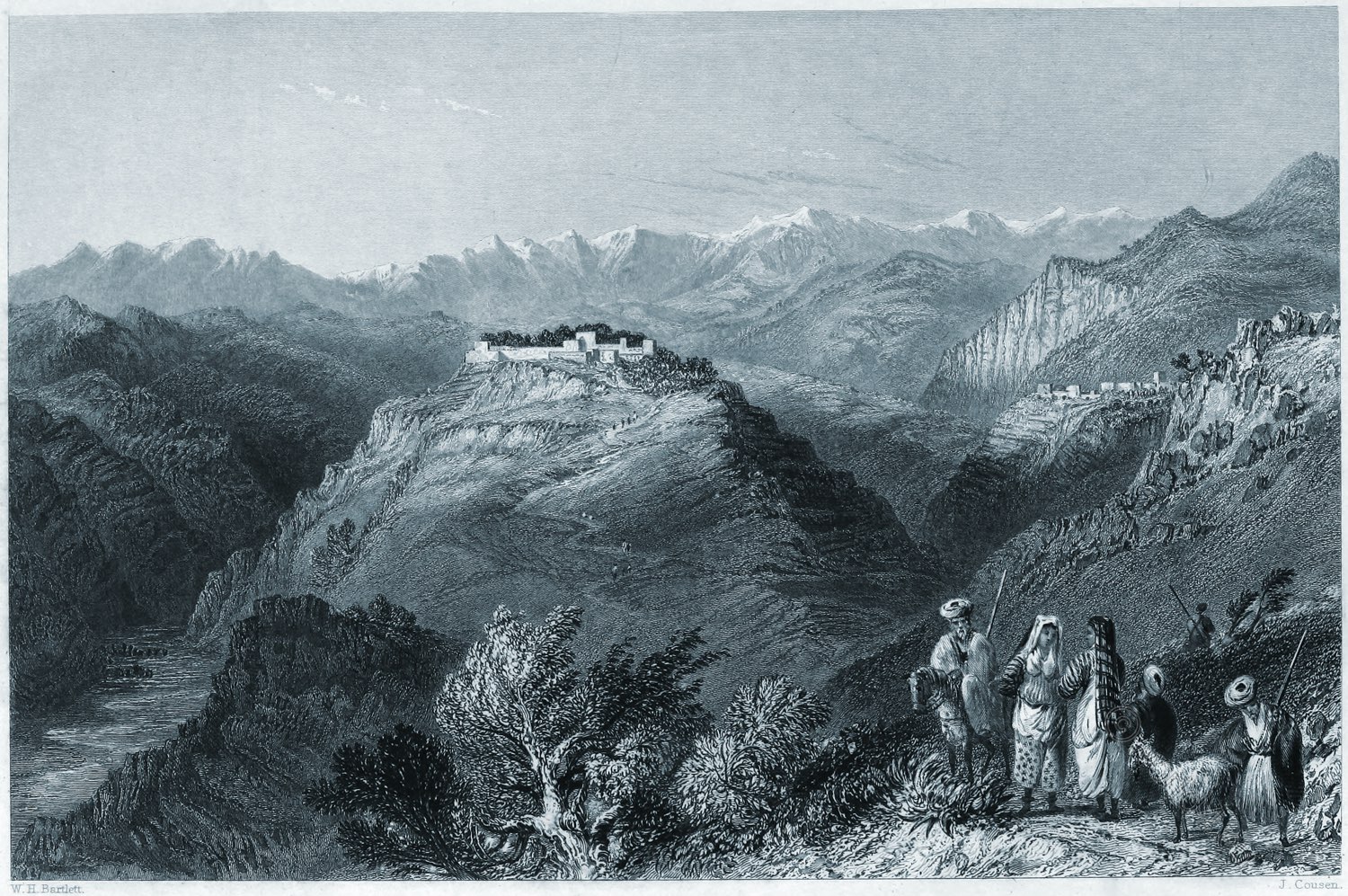

DJOUNI, THE RESIDENCE OF LADY HESTER STANHOPE

by William Henry Bartlett.

The view of the residence (Deir el-Sitt, a renovated former convent) of this celebrated woman is taken on the approach from Sidon: in its intricate, wild, convulsed appearance, this scene resembles many among the Apennines; the road is seen in front, winding up in a zig-zag course to the building; a kind of break-neck road, as if her ladyship wished to make the pilgrim toil and murmur to her dwelling, and, like Christian going up the hill Difficulty, “endure hardness” ere he reaches her bower of delights.

A more capricious choice of a home has never been made, in this world of caprice and eccentricity; the land abounds with sites of beauty and richness, vales and shaded hills, screened by loftier hills, with many waters. Lebanon has a hundred sites of exquisite attraction and scenery; but this woman, ever loving the wild and the fearful more than the soft things of this world, has fixed her eagle’s nest on the top of a craggy height that is swept by every wind.

The dark foliage that appears above its walls are the gardens, which are remarkably beautiful and verdant, the creation of her own hands. Nowhere in the gardens in the East is so much beauty and variety to be seen—covered alleys, pavilions, grass-plats, plantations, &c. in admirable order.

It was in a pavilion in these gardens that the artist had the honour of spending some hours in conversation with her ladyship. In the village on the right, he passed the night in the open air. The precipitous character of the glen between it and Djouni prevented his seeking the latter in the dark.

The high central chain of Lebanon, spotted with snow, shuts in the view. This mountain chain is here too monotonous to be either grand or beautiful; the path from Beteddein (Palace of the Druses) to Damascus crosses the summit, from which there is a view of vast extent over the sea, and inland as far as the waters of Merom, or lake of Tiberias. The costume of the women in the foreground is that in use in Lebanon.

In winter, in the rainy season, let not the resident of Djouni be envied by the humbler dwellers in the land, or by the recluses of the convents and monasteries which cover the declivities of Lebanon. If a quiet mind and a consoling faith be the chief ingredients of happiness in this world, they mingle but slightly in her ladyship’s cup the dreams and revelations of astrology have for many years past been the favourite excitement; without them the evening of her life would now be wretched, and she would feel like Norna of the Fitful head, when conscious at last that her power over the elements was a delusion.

Literature

Her views on the Christian revelation are as wild and unorthodox as some of her divinations: one of them is, that the Messiah is to come again, and shortly; the beautiful Arab steed, white as the driven snow, attended and served in the stables of Djouni with a care and luxury surpassed only by that of Commodus for his horse, is reserved for his especial use, when he shall enter Jerusalem in triumph; her ladyship is to follow in the train, on a brown mare of great beauty.

During the visit of the Rev. L. W. (not Wolff) to Lebanon, the Arab chiefs, lured by the report of his great wealth and influence, came in crowds to offer their flatteries, and their arms and services, if he purposed, as it was said, to set up some new dominion. His better sense, aided by a protracted illness, declined the temptation. He passed three days at Djouni, to which he was invited in order that his physician might attend a favourite domestic of its mistress.

Thus, under the same roof, were two of the wildest enthusiasts of the age, sternly opposed to each other in sentiment and purpose; the one devoting his wealth, and time, and talent, with undying zeal and sincerity, to the conversion of the Jews—traversing every land and city, entering the palaces of kings, that he might reclaim the lost race of Israel. A thousand pounds was not too much to expend for the conversion of a single Jew, nor a thousand miles too far to traverse to receive a Hebrew family into the fold.

On all such doings Lady H. looked with unutterable scorn and contempt. Unaware, however, of the career of her guest, she treated him with much civility. The denouement took place towards the close of his visit; it was highly characteristic. The guest had desired to find a suitable moment to lead her thoughts more earnestly to religion—such moments were rare at Djouni; however, as the hour of departure drew near, they were conversing, and she was indulging in some wild sallies, when he assumed a serious tone: he was listened to calmly, and with what he conceived at last to be a growing emotion; then there was a pause of a few moments. Was that proud heart touched? Only with surprise and indignation: there was a derisive smile, that was bitter to be borne. “I thought,” she said, “that i was entertaining a gentleman under my roof; but I see that I have harboured a fanatic missionary.”

It is said that those only are great actors, who, whether the part be a prince or peasant, act it with like intensity: this praise belongs to her ladyship, who has acted her character and played her part intensely, however changing and diversified it may have been.

During the first years of her abode in Syria, she often traversed the deserts, and was the very queen of Bedouins, à l’amazon, on a superb Arabian, spear in hand. When visiting the princes and pachas, admiration from the great, wonder and homage from those of lower rank, seldom failed to attend her: there was a cool daring and dignity in her bearing, a vigour and versatility in her conversation, to which in woman they were utterly unaccustomed.

The first act of the play was over; the buoyant strength of the spirit and frame began to give way; then came part the second, astrology: her beautiful steeds were idle in the stalls: the desert journeys and dangers were braved no more: the queen of Palmyra now sank into a nervous, home-keeping, retired woman the sheikhs and princes no longer saw the cavalcade of the “great lady” galloping to their gates. Yet a like enthusiasm, a like restless fervour, were now given to the dreams of superstition: she lives intensely on the future: the present has few charms, few joys: a failing health, declining age, no taste for active exertion, or even to leave for a day or an hour the walls and gardens of Djouni.

The third act of the drama is yet to be played: its close will scarcely be tragic; assuredly it will not be happy, or fortunate; but no woman could thus bear to see the “sere and yellow leaf” falling fast around her, could meet firmly the king of terrors in the halls of Djouni, friendless, faithless, desolate—save Lady H. Stanhope.

In the character of her mind there is an entire want of simplicity: she has ever the air of a dramatic being, of acting a part, whether it be to astonish the natives, or her visitors. In her interview with Lamartine, the mystifying of the astrologer is beautifully contrasted with the vanity of the poet. The following scene with the gentleman who drew this view of Djouni is interesting: no traveller hitherto has so lauded her personal charms.

“Around its portal were groups of wild-looking Albanians and Janissaries, and a most polite major-domo conducted us to our apartment, that was half English and half Oriental. In a few moments her ladyship sent for us, to conduct us round her gardens. I, who had expected a crabbed imperious old woman, was most agreeably surprised by the noble but gentle aspect of our strange hostess. In youth she must have been most beautiful: her features are remarkably fine, blending dignity and sweetness in a fascinating degree.

Her dress was fantastic, but impressive: her turban of pale muslin shadowing her high pale forehead. There is certainly a slight vein of fitful insanity in her expression, but its general and ordinary cast is that of one calmly persuaded of the truth of principles reposed on with deep satisfaction. She conducted us to an arbour in the gardens, quite English in appearance. I made this observation, when she replied! “Oh, don’t say so; I hate every thing English.” Then nodding to my companion, who was an American, “he has a good star-very good: “then addressing herself to me, “You are of a cheerful disposition, see every thing en couleur de rose; one of those beings who pass well through life.

You will rise about the middle of your life. You are apt to be violently angry on occasion, and I could let out more.” We then walked round the gardens, all of her own formation, and were surprised at their verdure and beautiful arrangement. We then retired to dinner: her ladyship’s nonentity of a meal had been previously taken. The dinner was most inspiriting, and my last lingering bitterness for the freak of last night was buried in an inimitable apricot tart. In the evening we were again sent for, and found her in a pavilion in the garden, reclining on an ottoman, with a long embroidered pipe: placed in a recess, her hand across her brow, she mutely scrutinised our features, as if to complete or confirm her fancied knowledge of our characters.

Coffee was served by a little Nubian girl. In the course of conversation, she said that the good genius would shortly appear; that the evil one was now on earth, busily employed in canvassing—that she knew of his whereabouts: that at the advent of the good genius, men would flock to his standard, leaving wives and children, and that a grand and decisive struggle would take place, to end in the establishment of the former. Our poor wild world will thus be called to order. I ventured to ask, whence originated so profound an acquaintance with futurity. Her ladyship with some hesitation replied, “Chiefly from reading.”

I noticed the similarity of these views to those entertained by Irving, founded on certain passages of scripture: “Irving,” she said, “must then be right:” she sometimes looked into the scripture for confirmation. But when she descended from the clouds to ordinary topics, she displayed great wit and penetration, which, with a fund of anecdote, and great fascination of manner, rendered our long familiar interview perfectly delightful. Her personal kindness too must not be forgotten: she advised me not to peril my life by visiting the disturbed districts, and offered me her hospitality, should I be willing to protract my stay in the mountains.”

Source: Syria, the Holy Land, Asia Minor illustrated in a series of views drawn from nature by John Carne, William Henry Bartlett, William Purser. Published by Fisher Sons & Co. London, Paris & America. c. 1836.