A History of mourning.

The Funeral of Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603) and Mary Stuart (1542-1587).

QUEEN ELIZABETH died in the seventieth year of her age and the forty-fourth of her reign, March 24, on the eve of the festival of the Annunciation, called Lady Day. Among the complimentary epitaphs which were composed for her, and hung up in many churches, was one ending with the following couplet: –

“She is, she was—what can there be more said ?

On earth the first, in heaven the second maid.”

It is stated by Lady Southwell that directions were left by Elizabeth that she should not be embalmed but Cecil gave orders to her surgeon to; open her. “Now, the Queen’s body being cored up,” continues Lady Southwell, “was brought by water to Whitehall, where, being watched every night by six several ladies, myself that night watching as one of them, and being all in our places about the corpse, which was fast nailed up in a board coffin, with leaves of lead covered with velvet, her body burst with such a crack that it splitted the wood, lead, and cere-cloth whereupon, the next day she was fain; to be new trimmed up.”

Funeral of Queen Elizabeth, 28th of April, 1603. — From a very rare contemporary engraving, reproduced expressly, and for the first time, for this work, by M. Badoureau, of Paris.

A history of mourning by Richard Davey.

No. 1 represents the wax effigy of the Queen lying on her coffin; gentlemen pensioners carrying the banners. The chariot is drawn by four horses. 2. Kings at Arms. 3. Noblemen. 4. The Archbishop of Canterbury. 5. The French Ambassador and his train-bearer. 6. The great Standard of England, carried by the Earl of Pembroke. 7. The Master of the Horse. 8. The Lady Marchioness of Northampton, grandmourner, and the ladies in attendance on the Queen. 9. Captain of the Guard. 10. Lord Clanricarde carrying the Standard of Ireland. 11. Standard of Wales, borne by Viscount Bindon, followed by the Lord Mayor. 12. Gentlemen of the Chapels Royal; children of the Chapels. 13. Trumpeters. 14. Standard of the Lion. 15. Standard of the Greyhound. 16. The Queen’s Horse. 17. Poor Women to the number of 266. 18. The Banner of Cornwall. The Aldermen, Recorders, Town Clerks, etc.

Elizabeth was most royally interred in Westminster Abbey on the 28th of April, 1603. We subjoin a rare contemporary engraving of the funeral procession, by which it will be seen with what pomp and ceremony the remains of the great Queen were escorted to their last resting-place. “The city of Westminster,” says Stow, “was surcharged with multitudes of all sorts of people, in the streets, houses, windows, leads, and gutters, who came to see the obsequy. And when they beheld her statue, or effigy, lying on the coffin, set forth in royal robes, having a crown upon the head thereof, and a ball and a sceptre in either hand, there was such a general sighing, groaning, and weeping as the like hath not been seen or known in the memory of man; neither doth any history mention any people, time, or state to make such lamentation for the death of a sovereign.” The funereal effigy which, by its close resemblance to their deceased sovereign, moved the sensibility of the loyal and excitable portion of the spectators at her obsequies in this powerful manner, was no other than the faded waxwork effigy of Queen Elizabeth preserved in Westminster Abbey.

A memento mori or death’s-head time piece, in solid silver, lately exhibited at the Stuart Exhibition, 1888-9. On the forehead is a figure of Death standing between a palace and a cottage: around is this legend from Horace, “Pallida mors equo pulsat pede pauperum tabernas Regum que turres.” On the hind part of the skull is a figure of Time, with another legend from Ovid: “Tempus Edax Rerum tuque Mirdiosa Vetustas.” The upper part of the skull bears representations of Adam and Eve and the Crucifixion between these scenes is open work to let out the sound when the watch strikes the hour upon a silver bell which fills the hollow of the skull and receives the works within it when the watch is shut. On the edge is inscribed “Sicut meis sic et omnibus idem.” It bears the maker’s name, Moysart à Blois. Belonged formerly to Mary Queen of Scots, and by her was given to the Seton family, and inherited thence by its actual owner, Sir T. W. Dick Lauder.

A history of mourning

Elizabeth was interred in the same grave with her sister and predecessor in regal office, Mary Tudor. Pier successor, James I., has left a lasting evidence of his good feeling and good taste in the noble monument he erected to her memory in the Abbey, and she was the last sovereign of this country to whom a monument has been given.

We have very minute details of how royal personages were buried in France, in a curious book published in the 17th Century, from a MS. of the time of Louis XI. In it we learn that King Louis XI. wore scarlet for mourning on the death of his father, Charles VII. Up to the time of Louis XIV. the Queens of France, if they became widowed, wore white; and this is the reason that Mary Tudor was called “La Heine Blanche,” when she clandestinely married the Duke of Suffolk in the chapel of that most interesting place, the Maison Cluny, now a museum, which still retains its name of La Reine Blanche. The Queen had been but a very short time the widow of Charles VIII., and still wore her weeds when she gave her hand to the lusty English duke. Mary Stuart wore white for her husband, Francis II. of France; and when she arrived in Scotland she still retained, for some months, her white robes, and was called the “White Queen” in consequence.

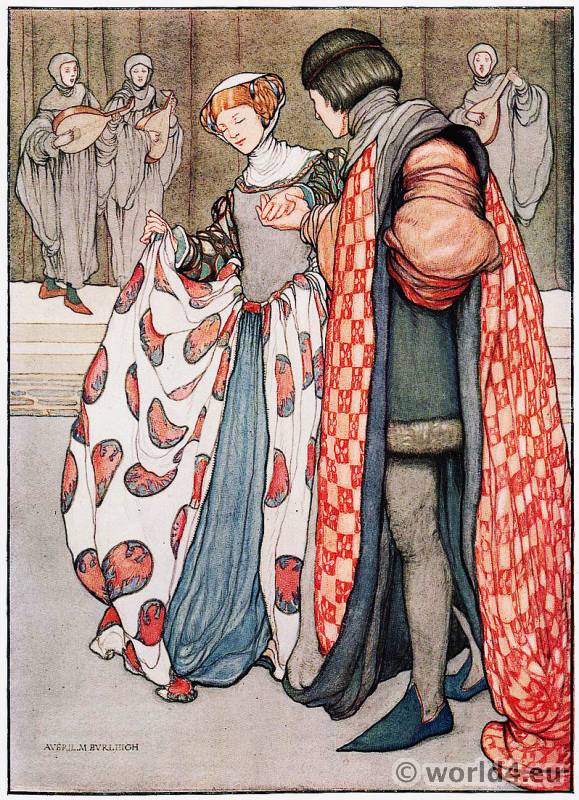

French Lady of the 16th Century in Widow’s Weeds. This costume is identical with that worn by Mary Stuart as widow of the Dauphin only her dress was, perfectly white. — From Pietro Vercellio’s famous work on Costume, engraved expressly for this publication.

A history of mourning

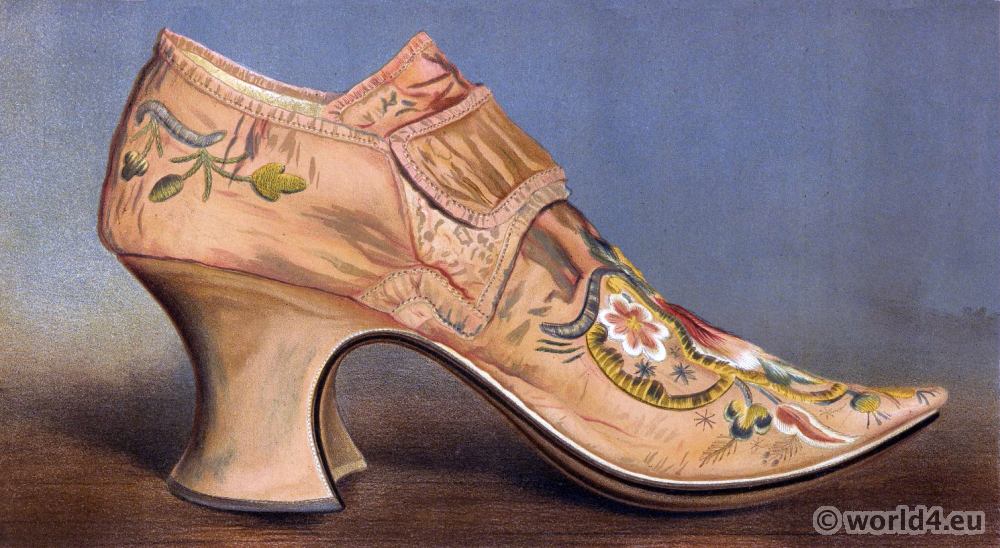

But this illustrious and ill-fated princess throughout the greater part of her life wore black, and we have many minute details of her dresses, especially of the stately one she wore on the day of her execution, which was of brocaded satin, having a train of great length a ruffle of white lawn, edged with lace and a veil (which still exists) made of drawn ‘ threads, in a check-board pattern, and edged with Flemish lace. From her girdle was suspended a rosary, and in her hand she carried a crucifix. Her undergarments, we know, were scarlet for, when she removed her dress upon the scaffold, the bodice at least, all contemporaries agree, was flame-coloured. Queen Elizabeth ordered her Court to go into mourning for the Queen of Scots, whose sad and “accidental” death she hypocritically decreed should be regarded as a very great misfortune.

King James ordered the deepest mourning to be worn for his royal mother—a requisition with which all his nobles complied, except the Earl of Sinclair, who appeared before him clad in steel. The King frowned, and inquired if he had not seen the order for a general mourning. “Yes,” was the noble’s reply; “this is the proper mourning for the Queen of Scotland.” James, however, whatever his inclinations might have been, was unprovided with the means of levying war against England, and his Ministers were entirely under the control of the English faction, and, after maintaining a resentful attitude for a time, he was at length obliged to accept Elizabeth’s “explanation” of the murder of his mother.

Early in March, 1587, the obsequies of Mary Stuart were solemnised by the King, nobles, and people of France, with great pomp, in the Cathedral of Notre Dame at Paris, and a passionately eloquent funeral oration was pronounced by Renauld de Beaulue, Archbishop of Bourges and Patriarch of Aquitaine, which brought tears to the eyes of every person in the congregation.

After Mary’s body had remained for nearly six months apparently forgotten by her murderers, Elizabeth considered it necessary, in consequence of the urgent and pathetic memorials of the afflicted servants of the unfortunate princess and the remonstrances of her royal son, to accord it not only Christian burial, but a pompous state funeral. This she appointed to take place in Peterborough Cathedral, and, three or four days before, sent some officials to make the necessary arrangements for the solemnity.

The place selected for the interment was at the entrance of the choir from the south aisle. The grave was dug by the centogenarian sexton, Scarlett. Heralds and officers of the wardrobe were also sent to Fotheringay Castle to make arrangements for the removal of the royal body, and to prepare mourning for all the servants of the murdered Queen. Moreover, as their head-dresses were not of the approved fashion for mourning in England, Elizabeth sent a milliner on purpose to make others, in the orthodox mode, proper to be worn at the funeral, and to be theirs afterwards. However, these true mourners coldly, but firmly declined availing themselves of these gifts and attentions, declaring “that they would wear their own dresses, such as they had got made for mourning immediately after the loss of their beloved Queen and mistress.”

On the evening of Sunday, July 30, Garter King of Arms arrived at Fotheringay Castle, with five other heralds and forty horsemen, to receive and escort the remains of Mary Stuart to Peterborough Cathedral, having brought with them a royal funereal car for that purpose, covered with black velvet, elaborately set forth with escutcheons of the arms of Scotland, and little pennons round about it, drawn by four richly-caparisoned horses. The body, being enclosed in lead within an outer coffin, was reverently put into the car, and the heralds, having assumed their coats and tabards, brought the same forth from the castle, bare-headed, by torchlight, about ten o’clock at night, followed by all her sorrowful servants.

The procession arrived at Peterborough between one and two o’clock on the morning of July 30, and was received ceremoniously at the minster door by the bishop and clergy, where, in the presence of her faithful Scotch attendants, she was laid in the vault prepared for her, without singing or saying—the grand ceremonial being appointed for August 1. The reason for depositing the royal body previously in the vault was, because it was too heavy to be carried in the procession, weighing, with the lead and outer coffin, nearly nine hundred- weight.

On Monday, the 31st, arrived the ceremonial mourners from London, escorting the Countess of Bedford, who was to represent Elizabeth in the mockery of acting as chief mourner to the poor victim. At eight in the morning of Tuesday the solemnities commenced. First, the Countess of Bedford was escorted in state to the great hall of the bishop’s palace, where a representation of Mary’s corpse lay on a royal bier.

Thence she was followed into the church by a great number of English peers, peeresses, knights, ladies, and gentlemen, in mourning. All Mary’s servants, both male and female, walked in the procession, according to their degree—among them her almoner, De Preau, bearing a large silver cross. The representation of the corpse being received without the Cathedral gate by the bishops and clergy, it was borne in solemn procession and set down within the royal hearse, which had been prepared for it, over the grave where the remains of the Queen had been silently deposited by torchlight on the Monday morning. The hearse was 20 feet square, and 27 feet high. On the coffin—which was covered with a pall of black velvet—lay a crown of gold, set with stones, resting on a purple velvet cushion, fringed and tasselled with gold.

All the Scotch Queen’s train—both men and women, with the exception of Sir Andrew Melville and the two Mowbrays, who were members of the Reformed Church—departed, and would not tarry for sermon or prayers. This greatly offended the English portion of the congregation, who called after them and wanted to force them to remain. After the prayer and a funeral service, every officer broke his staff over his head and threw the pieces into the vault upon the coffin. The procession returned in the same order to the bishop’s palace, where Mary’s servants were invited to partake of the banquet which was provided for all the mourners but they declined doing so, saying that “their hearts were too sad to feast.”

Source: A history of mourning by Richard Davey. Publisher London: Published at Jay’s, 1890.

Related: