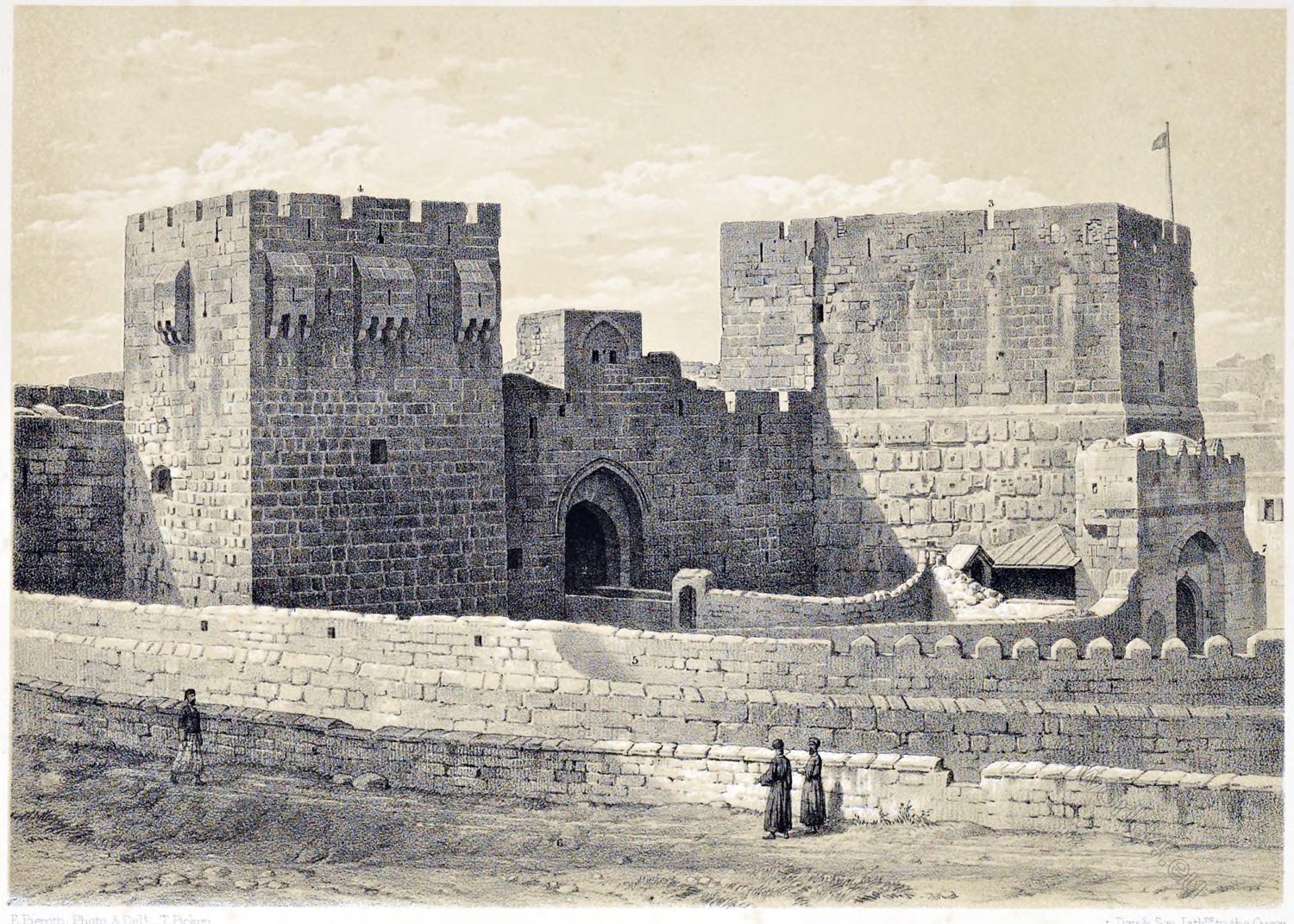

Yedikule, the “Castle of the Seven Towers”, is located directly on the Theodosian Land Wall (Turkish: Teodos II Suru). It is part of an approximately 20-kilometre-long fortification in Istanbul built at the beginning of the 5th century under Emperor Theodosius II.

The complex is located directly on the wall. It is partly of Byzantine and partly of Ottoman origin. Its towers are connected to each other by thick walls. The Ottomans used it as a dungeon, treasury and execution site.

The most famous execution victims of Yedikule were the eighteen-year-old Sultan Osman II, who was strangled in one of the towers on 20 May 1622, and the last emperor of Trapezunt, David Komnenos.

PRISON OF THE SEVEN TOWERS

by Thomas Allom.

At the extremity of the land-wall of Constantinople, where it meets the sea of Marmora, rises an enclosure flanked by battlemented towers. It is the first object seen by Frank ships, and thus the stranger is presented with a prospect that reminds him of the most striking and singular usage of Turkish despotism.

This enclosure, and the towers, existed under the Greek empire, and were called “Heptapurgon,” from the number of the castles included. They were first erected by Zeno, and enclosed by the Comneni, and were employed as a prison for state offenders.

When the Turks took pos- session of the city, the Sultan appropriated them as a secure place to deposit his plunder. They afterwards reconverted them to their original purpose of a state prison, and added a feature peculiarly their own.

The character of an ambassador, held sacred by all other nations, was here violated. The first symptoms of a rupture between the Turks and a foreign state, was, to seize the resident minister, and incarcerate him in this prison ; and the European states, instead of revolting against this barbarous outrage on the laws of nations, quietly submitted to it, as they did to the oppression of the Barbary pirates, because each rejoiced, and felt itself elated, at the degradation of the other.

Mr. Beaufeu, a French minister, confined there, made his escape; and the Sultan was so enraged, that he immediately caused the governor to be strangled in his own prison. Since then, the Turks are not disposed to admit strangers, lest they might discover the secrets of their prison-house. This barbarous custom continued so late as the year 1784, when the Russian envoy was sent there, as the first act of hostility.

The lights and usages of civilised Europe began immediately after to dawn on the East. The just and amiable Selim discontinued the practice, and the present Sultan has abolished it altogether. It was generally supposed the custom would be renewed, and the Sultan would think him- self justified in imprisoning the ambassadors of all the powers leagued against him at Navarino, in retaliation for that wanton and unprovoked attack; but he suffered them quietly to depart, and set an example of moderation, and scrupulous regard to the law of nations, which European states might do well to imitate.

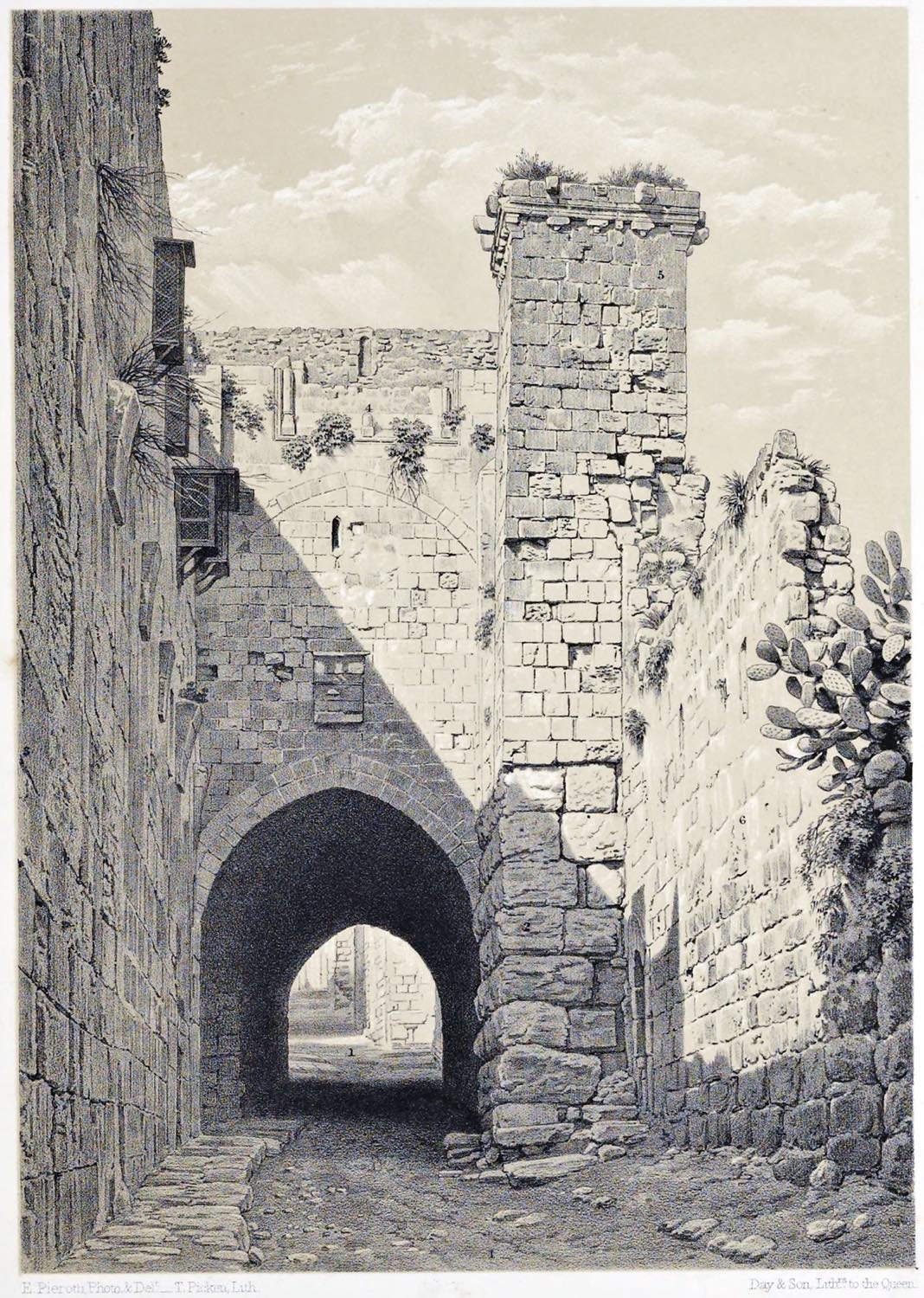

While used as this extraordinary prison, the strangest tales of mystery were whispered about, and are still told to visitors. A cavity is shown, called “the well of blood,” which imagination still pictures as overflowing with human gore, and its stained and darkened sides countenance the tradition. In another place is “the cavern of the rock,” where confession was extorted from the unhappy prisoners.

A number of low arches are also pointed out, into which the wretched victims were compelled to force themselves, too low to admit their bodies through the aperture, and from whence they could not again extract them—and there they were left to perish with hunger. Places, too, are still shown, where skulls were piled so high as to rise above the surrounding walls.

The towers were originally seven in number, but are now reduced to four. Three of them were thrown down by the great earthquake in 1786. They were never rebuilt by the Turks; yet they still call them “yedde-kule,” or the seven towers. The buildings themselves are exceedingly unsightly.

They are octagonal with conical roofs. The most conspicuous, represented in the illustration, was somewhat of a better order. It is that in which the foreign ambassadors were confined, and the apartments assigned to them were not very inconvenient.

Connected with this edifice was the celebrated “Chrysopule,” or golden gate, so renowned for its splendour under the Greek empire. It opened into the area, and was one of the entrances to the Seven Towers. It was covered with some beautiful sculptures in basso-relieve, which were considered chef-d’oeuvres of art, and among them Venus holding her torch over the sleeping Adonis, to examine his beauties. Its position is on the right of the illustration. In the distance is the romantic archipelago of the Princes’ Islands, on one side, and on the other, the promontory of Scutari.

Source: Constantinople and the scenery of the seven churches of Asia Minor illustrated. In a Series of drawings from nature by Thomas Allom (1804-1872). With an historical account of Constantinople, and descriptions of the plates by the Rev. Robert Walsh LL.D. (1772-1852). Fisher, Son, & Co, 1839. Newgate St., London; & Quai de L’Ecole, Paris.

Photography: Istanbul – Castell de Yedikule. 30 January 2008. © by Lohen11 (Josep Renalias). This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.