THE BENEDICTINES.

ST. BENEDICT. – HIS RULE. – THE HABIT OF HIS MONKS. – PROPAGATION OF THE ORDER. – CLUNY. – FULDA. – BURSFELD. – ENGLISH BENEDICTINES. -BENEDICTINES IN THE UNITED STATES.

I. THE ORDER IN GENERAL.

THE religious state, which had gradually been developed and perfected in the East by the rule of St. Basil, reached its fullest development in that of St. Benedict. Before the time of the saint, there had been monasteries in the West, certainly: St. Athanasius had made the religious state known to it, Cassian had communicated it to Gaul, and it had penetrated to the British Isles, but it was reserved to Saint Benedict to establish it upon a solid basis.

This saint was born at Nurcia, in the diocese of Spoleto, about the year 480. At an early age, he fled from Rome, whither he had been sent to study, fearing lest the world should contaminate his heart, and he betook himself to the desert of Subiaco. Here he received the religious habit from a monk called Romanus, and took up his abode in an almost inaccessible grotto. Here, too, he was severely tempted. The recollection of a woman whom he had seen at Rome was the cause of of this; but to overcome the temptation, be mortified his body and thus subjected it to the spirit. This victory of St. Benedict affords a great lesson. If the saint had yielded, the world might have been forever deprived of the Benedictine order, and humanity might have suffered an irreparable loss; so true it is that causes apparently small have sometimes immense consequences. The world owes an eternal debt of gratitude to the victory which St. Benedict gained over his temptation. His sanctity could not remain concealed.

The monks of a monastery situated between Subiaco and Tivoli, having heard of him, earnestly desired that he should become their abbot. He yielded to their importunities, but his disappointment must have been great when he discovered that their conduct was far from being edifying. The monks, tired of his remonstrances, soon regretted their choice, and some of them even attempted to poison him. The saint then left them and returned to his former solitude. God again sent him other disciples, and, in a short time, he built twelve monasteries at Subiaco, in each of which he placed twelve religious with a superior, he, however, remaining at the head of all. Thus were laid the foundations of the great Benedictine order.

The enmity of a bad-priest again forced him to leave Subiaco, and he repaired to Monte Casino, where he destroyed some last vestiges of idolatry that there existed. Here he built a large monastery which was destined to become famous and act an important part in the history of the Middle Ages. He triumphed over all obstacles and beheld his work blessed by God. It was here that the great founder of the greatest of all religious orders ended his days in peace in the year 543.

The Rule of St. Benedict, as Montalembert remarks, is the first that was written in the West and for the West; it was the product of the genius of its author, who supplied what was wanting to that of St. Basil. Its two fundamental principles and its foundation are labor and obedience. It was the model of all rules which followed, and it contained in substance whatever they worked out in detail. St. Benedict was an instrument in the hands of Divine Providence, raised up for the regeneration of society, although he does not appear to have foreseen the results of his work. He lived only in the present, for his own and his monks’ salvation, but his influence was to be felt through future generations, and he was to be the founder of an empire that would triumph upon the ruins of Rome, and last long after Byzantium had fallen. His rule was austere, but it contained the essence of the religious life and the fullest practice of the evangelical councils.

The Order of St. Benedict, by the will of its holy founder, was open to all kinds of persons without distinction, even children being received into it. The latter had their dormitory separate from that of the religious, and the novices had also. theirs apart from the others. The beds were separated by curtains or boards. The monks were divided into tens, over each of which a dean was placed, while the prior presided over the entire community. The power of the abbot over the religious was absolute, and he was to govern them more by his example than by his authority. The cellares had charge of the temporal affairs of the house. The religious were all obliged to perform their share of domestic labor. They were bound to recite the Divine Office, of which St. Benedict himself laid down the rules. From the first of November until Easter they arose at two in the morning. The time which remained after Matins was spent ill reading and meditation. After Prime they betook themselves to work until ten; but from the first of October until Easter, work began at Tierce and lasted until None, or three in the afternoon.

In the beginning of the order, Mass was only said on Sundays and solemn feasts, and, on that occasion, all the religious received Holy Communion. After dinner, reading and work began again. Manual labor was proportioned to the strength of each one. At meal time, each religious received two portions, and sometimes a third. There was no fast between Easter and Pentecost; but from Pentecost to the 13th of September, every Wednesday and Friday was a fast-day. The great daily fast lasted from the 13th of September until Easter. During Lent fasting became more rigorous and the religious did not eat until evening. The use of flesh meat, at least of quadrupeds, was never allowed, except to the sick. Even the children were subject to this rule. The receiving of young children into the Benedictine monasteries became afterwards a cause of relaxation of discipline, and it was consequently abolished.

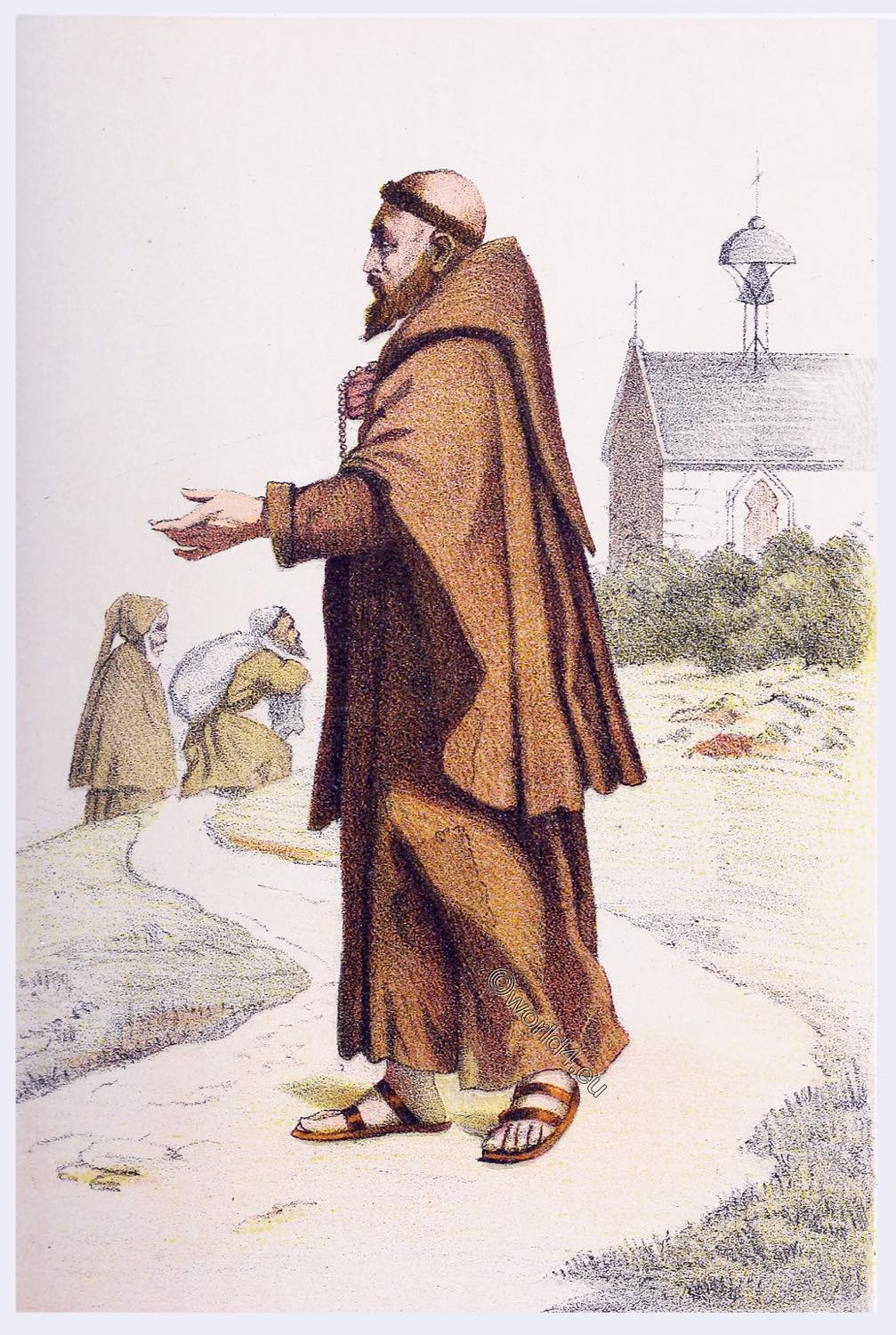

As regards the habit of the religious, Saint Benedict determined nothing concerning the color. It appears, says Hélyot, that the habit of the ancient Benedictines consisted of a white tunic and black scapular. It was to be regulated to a great extent by the climate of the place. The Benedictines took vows of obedience and stability.

Even during the life of the founder the Benedictine order began to spread. The first foundation was that of Sicily, to which Saint Placidus was sent by the saint himself. This was followed by a foundation in France where Saint Maurus, another disciple of Saint Benedict, established a monastery at Glanfeuil. It is not certain when the order was first introduced into Spain. It probably entered into England with Saint Augustine, who, in company with several monks, was sent by Pope Gregory the Great to evangelize the Anglo-Saxons. The Benedictines grew to be very powerful in England, where they possessed many monasteries until the reign of Henry VIII. The order sent forth its missionaries to the heathen nations of the north of Europe, which they gradually converted to Christianity. St Willibrord, Apostle of the Frisians; St. Boniface, who preached the Gospel to the Germans, and other missionaries were probably Benedictine monks, who founded monasteries in various places.

In course of time, relaxations crept into the order, in consequence of which numerous reformations have taken place. One of the oldest of these was that effected by St. Benedict of Aniane in the ninth century. The saint, being appointed superior of the abbeys in France, a council held at Aix-la-Chapelle, in the beginning of the same century, enacted several decrees of reformation for the order, although in a few minor details it mitigated the rule. The Order of Saint Benedict, having spread over the whole of Europe, was in course of time divided into various congregations. One of the most important of these was that of Cluny.

II. CLUNY.

The monastery of Cluny was founded by William, Duke of Aquitaine, about the year 910, with St. Berno as the first abbot. Several monasteries were erected in course of time, which remained subject to the abbot of Cluny. Pope Agapetus II, in 946, exempted the Congregation of Cluny from the jurisdiction of the ordinaries of dioceses, and subjected it immediately to that of the Holy See. In many of the monasteries of France, England, and Spain, regular Observance had been neglected to such an extent that the very name of St. Benedict’s rule had become almost obsolete, for after the death of St. Benedict of Aniane, the order had again degenerated. Cluny, however, gave a magnificent example of religious observance, and drew numerous monasteries to the imitation of its virtue. The Divine Office was always there celebrated with great solemnity, silence was observed with the utmost exactitude, and the monastery was also noted for its charity toward the poor, so much so, that in the beginning of Lent, food was distributed to seven thousand indigent persons. The reputation of the Order of Cluny spread over the face of Europe, and monasteries subject to its jurisdiction were founded not only in France, but also in Germany, England, Spain, Italy, and even in the East. Father Mabillon is of opinion that the custom of attaching oblates to the order began at Cluny.

However, all earthly things are subject to decay, nor did the Order of Cluny form an exception. Ponce, the seventh abbot, did not walk in the footsteps of his saintly predecessors, and his conduct produced division in the monastery. The evil caused by this man was nevertheless remedied to a great extent by his successor, Peter the Venerable, who made several regulations which tended to strengthen the observance. In course of time, relaxations were again introduced, and the custom of eating meat began in the order. Measures of reform were taken at various intervals. but, after 1528, John of Lorraine, having become commendatory abbot of Cluny, the order became greatly relaxed.

In the seventeenth century, the reform known as that of the Strict Observance of Cluny, was effected. principally through the efforts of Cardinal de Richelieu. At the epoch of the French Revolution, however, the Order of Cluny was suppressed by the civil government, and it disappeared. The religious of the order wore a black habit.

III. FULDA.

The Congregation of Fulda was one of the ancient branches of the Benedictine order. The abbey of that name had been founded by St. Boniface, Apostle of Germany. It was situated between Hesse, Franconia, and Thuringia, in the present Province of Hesse-Nassau. In course of time it became subject to the immediate jurisdiction of the Holy See, and its riches were greatly augmented. It was in this monastery that the celebrated Rabanus Maurus flourished in the ninth century. Like other similar institutions it had its vicissitudes of relaxation and reformation. The Congregation of Fulda exists at present, as I was told by a Benedictine abbot, only in its female branch.

IV. CONGREGATION OF BURSFELD IN GERMANY.

The Congregation of Bursfeld was begun by John of Meden, religious of the abbey of Rheinhausen, who, on his return from the Council of Constance, held in 1414, endeavored in vain to persuade the monks of the abbey to accept the reforms which the Council desired to introduce. He then established himself at the abbey of Cluse, when, with several novices, he began to practise the strict observance. He afterwards obtained the ruined abbey of Bursfeld, founded in 1098, by Henry, Count of Northeim, and there he took up his abode. Many monasteries afterwards accepted the reform, and, in 1464, they were united into one congregation, of which John of Hagen, successor of John of Meden, as abbot of Bursfeld, became president.

V. CONGREGATION OF ST. MAURUS.

The congregation which bore this name was one of the most illustrious of the Order of St. Benedict, both in virtue and in science. The Council of Trent, which was brought to a close in 1563, had decreed that independent monasteries should either be united into congregations or be submitted to undergo the visits of the bishops. In consequence of this, several Benedictine monasteries in France united, rather, as Hélyot remarks, to withdraw from the jurisdiction of the bishops than for the sake of reformation. The evil was so deeply rooted that Cardinal Charles de Lorraine, Papal Legate in the dioceses of Metz, Toul, and Verdun, proposed to Pope Clement VIII. to suppress the Order of St. Benedict in the provinces of his legation. But God had in store a better means to bring about the desired reformation; Dorn Didier de la Cour, religious of the Abbey of St. Vanne at Verdun, was chosen by Divine Providence to inaugurate it.

The relaxation of the monks in France had at first caused him to think of entering another order; he consulted on this subject several enlightened persons, but he was advised to remain in his condition and to lead as regular a life as was possible. After ten months of solitude and penance, he finally joined the Minims, who gave him their habit. He could not, however, forget the Order of St. Benedict, and, leaving the Minims, returned to his monastery of St. Vanne, determined to work at its reformation. God paved the way for him, for, being elected Prior, he began the work by means of the new subjects he received into the order. This was the origin of the Congregation of St. Vanne and St. Hidulphe. Becoming too extended, it was divided, in 1618, into two separate congregations, of which that of St. Maurus was the second. The latter was thus named in honor of the disciple of St. Benedict, who had introduced the order into France. It soon spread throughout the kingdom, and it was confirmed by Pope Gregory XV., who granted to it the same privileges that had been accorded to the Congregation of St. Vanne. In 1633 it obtained the celebrated Abbey of St. Denis, at which time it possessed more than forty monasteries; the following year it was united to the Congregation of Cluny, but this union was again dissolved in 1644. In the eighteenth century it was divided into six provinces, governed by a general.

The Congregation of St. Maur applied itself in an especial manner to the education of the youthful members of the order. To this end each province had its novitiate, from which the newly-professed members were transferred to one of the monasteries where, during two years, they were trained in the practice of piety and of the ceremonies of the order. Five years more were devoted to the study of philosophy and theology, after which a year was spent exclusively in spiritual exercises as a preparation for the priesthood.

The Benedictines of the Congregation of St. Maur did not entirely concentrate their activity within their monasteries, but gave a share of their works to the good of their neighbor by the preaching of the word of God, the administration of parishes, and the education of youth. They became celebrated for their learning and writings. They edited a number of manuscripts which thus far had lain hidden in libraries, besides several new editions of the works of the Fathers. One of the most celebrated of their members, Dom Mabillon, who died in 1707, edited thirty volumes on various subjects. He is the author of the Li ves of the Saints of the Order of St. Benedict and of the Annals of the same order. This work was continued by Dom Ruinart.

Unfortunately for the Congregation of St. Maur, it also had its period of decadence of religious fervor. The Bull Unigenitus, issued against the errors of Jansenius, was opposed by many members of the congregation, and although the superiors remained submitted to the authority of the Pope, Jansenism played havoc in the order, and a spirit of extreme relaxation was introduced. But the French Revolution was at hand. The Congregation of St. Maurus, together with other religious orders, was swept from France. Its last general was Dom Chevreux. The religious left their monasteries in 1792. In the beginning of this century an attempt was made to resuscitate the ancient Congregation of St. Maurus, but it proved a failure.

There exists at present in France a new Congregation of Benedictines founded at Solesmes, which has also taken the name of St. Maurus, and which is rendering itself illustrious by its intellectual activity.

VI. BENEDICTINES IN THE BRITISH ISLES.

The Benedictines, as well those of the Order of Cluny, as of other monasteries, had been suppressed in England by Henry the VIII. in 1536. They were again restored at the accession of Queen Mary, but Elizabeth having succeeded her, the order was once more suppressed, At the end of the sixteenth century the ancient English Benedictine Congregation was again revived on the continent of Europe, and it continued to send its missionaries into England. The monks of this congregation observe the rule of St. Benedict with certain dispensations granted to them by the Holy See.

We may here make a passing mention of the Scotch Benedictines who established various houses in Germany, and differed from their brethren in their rites and in the color of their habit, which was white. At present, however, they wear black, like the other members of the Order of St. Benedict.

In Ireland there existed a few Benedictine monasteries, but the order does not appear to have taken deep root on that island, so renowned on account of its monastic spirit. There was a monastery at Ross, which is supposed to have been of the Benedictine rule, and to have been subject to the abbey of Wurzburgh, in the Province of Metz in Germany. A priory of the same order was founded, in 1185, at Waterford, by John, Earl of Morton. It was very wealthy, and it possessed, as a dependency, St. John’s House of Benedictines at Youghal, founded about the year 1360. Another Benedictine monastery was established before the year 1210, by John de Courcy, at Black Abbey, two miles north of Ballyhalbert, in the county of Down. It was subject to the Abbey of St. Mary, at Lonly in Normandy. The same nobleman replaced the Canons in an abbey at Downpatrick by Benedictine monks, from the Abbey of St. Werburgh, in Chester, in the year 1183. In 1380, Parliament decreed that no Irishman should be professed in that monastery. Its superior had the seat of a baron in Parliament. It existed until the time of the Suppression. At a much earlier period, about the year 948, a Benedictine abbey had been founded at Dublin, most probably by the Danes, shortly after their conversion to Christianity. In 1139, it passed into the hands of the Cistercians. It bore the title of Abbey of the Virgin Mary.

VII. OTHER CONGREGATIONS.

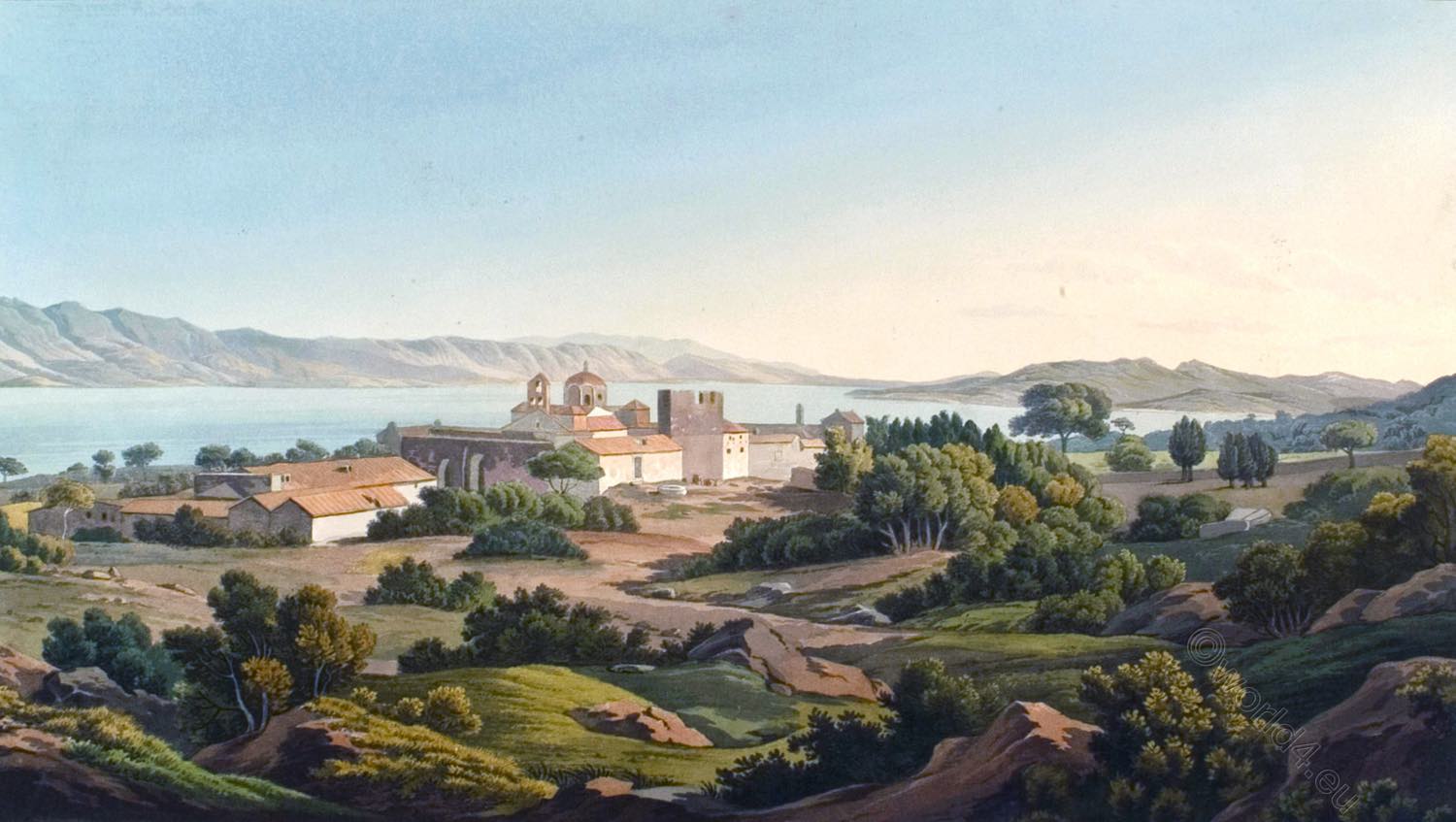

One of the most venerable of the Benedictine congregations is that of Monte Casino in the Province of Frosinone, Italy. It was on that hallowed spot that St. Benedict established his great monastery, whence the order spread over the world. It was destroyed by the Lombards in 500, but again rebuilt in 720. This celebrated abbey shared in all the vicissitudes of ecclesiastical history, and, even in our own days, it has its part of the sufferings which the Church endures. It was within its hallowed walls that the great St. Thomas Aquinas received his early education in the thirteenth century.

The present Casinese congregation first bore the name of Congregation of Saint Justina, from an abbey of that name at Padua, belonging to the Congregation of Cluny. The latter order, with other Benedictines, had fallen into great relaxation in Italy, but a reformation began at the said monastery about the year 1408, which culminated in the establishment of the Congregation of Saint Justina. In the year 1504 the monastery of Monte Casino, having been united to that congregation, the name was changed by order of Pope Julius II. The Congregation of Monte Casino exists to the present day, and it is now sub-divided into nine congregations.

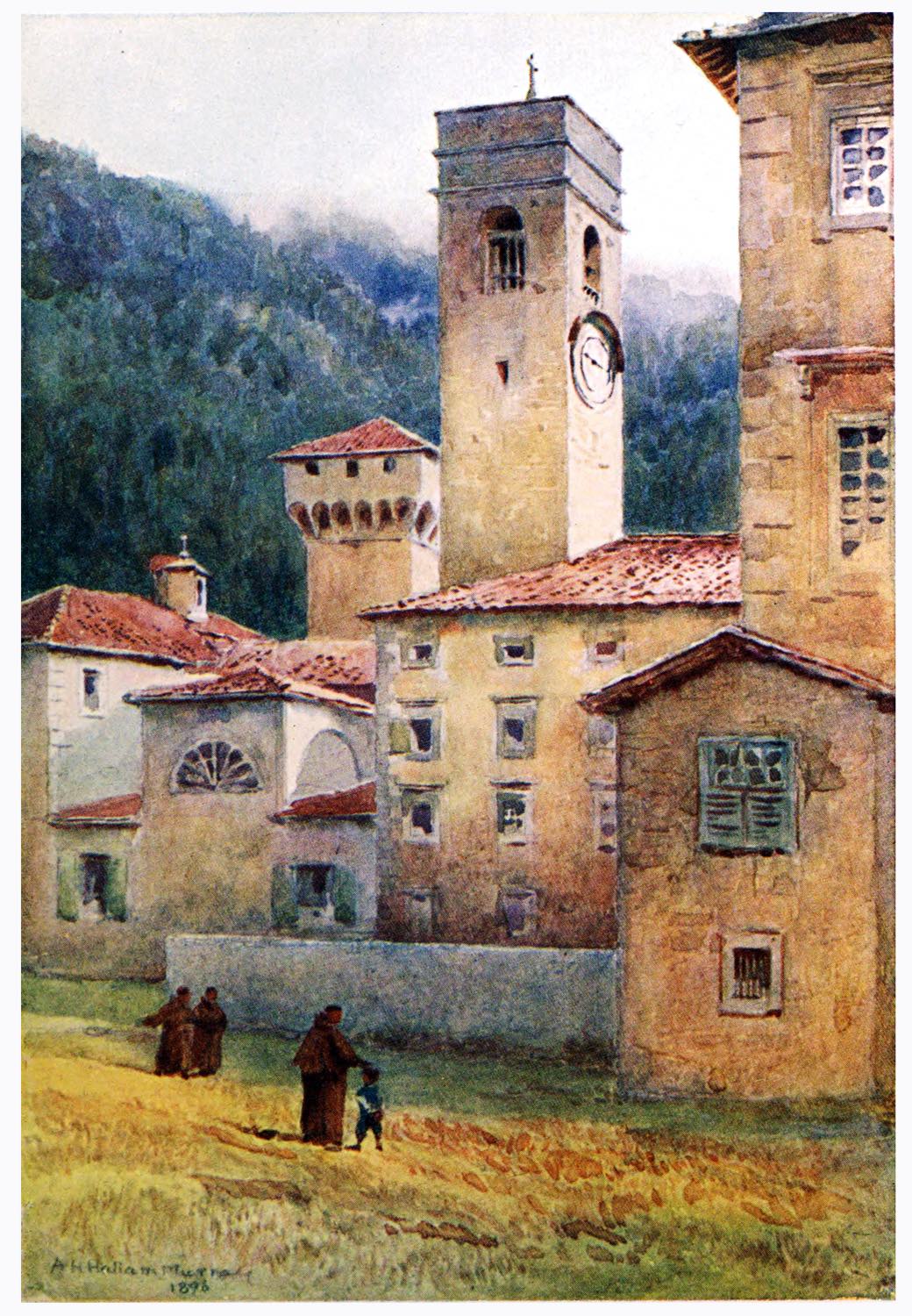

In the beginning of the fifteenth century a reformation of the Benedictine order was begun at the abbey of Molck in Austria (Melk Abbey or Stift Melk), which gave rise to a congregation, called of Molck, established in 1625. Other congregations were in course of time established in Germany, such as those of Suabia, Saltzbourg, Bavaria, and Switzerland. There exists in France a branch of the Congregation of Monte Casino, founded in this century, at Pierre qui Vire by the abbé Muard.

These religious lead a very austere life, and combine contemplation with missionary labors. They have a foundation in the United States in Oklahoma Territory. The founder of this congregation, Marie Jean Baptiste Muard, was born on April 24th, 1809. After having been successively parish priest of Joux la-Ville and St. Martin d’Avallon, he founded the Monastery of the Sacred Heart of Jesus and the Immaculate Heart of Mary at Pierre qui Vire in 1850, under the rule of St. Benedict. In his address to his brethren he gives the reason why that rule was chosen in preference to any other. We quote his words: “I felt a predilection for an ancient rule, because those rules have an odor of sanctity not to be found to the same extent in the more recent ones and because they have the sanction of time and experience, and, lastly, because in these times there is a tendency to return; to the ancient monastic usages.

“Now among the most ancient rules, that of St. Benedict possesses all the desired conditions. It appears as the most perfect daughter of the primitive Oriental rules, as the mother of all those of the West, as the sacred code which has regulated the monastic world for more than fourteen hundred years, as the most venerable of all on account of the profound wisdom and eminent sanctity shining forth from its every page, the perfection of the religious life it establishes, its divinely-ordered entirety, marvelous order, and its admirable details.” To this rule Father Muard added various constitutions which he had gathered from the most approved sources. The original rule of fasting was modified, while that of abstinence was rendered more austere. He decreed that not only the individual members, but the society itself should be poor, forbidding it to possess any fund, or even land.

After the death of Father Muard, the austerity of some of the constitutions was modified by Pius IX., and by a decree of January 14th, 1859, the monastery of Pierre qui Vire was canonically erected and affiliated to the Benedictine congregation of Subiaco. The points of the constitutions which had been modified were these: The religious were allowed to own the soil on which their monastery was built, and further to use all kinds of food permitted by the original rule of St Benedict.

The Society of Pierre qui Vire has founded several monasteries in France, one in Spain, another in Ireland, near Dublin, and one in Oklahoma Territory in America. *)

The other monks of the Order of St. Benedict date the commencement of their history in this country from the year 1846, when monks from the abbey of Wetten, in Bavaria, established a foundation in Pennsylvania.

*) The Life of Rev. Mary John Baptist Muard, by the Abbé Burles, translated by Rt. Rev. Isidore Robot, O.S.B.

In the beginning of the 19th century, all the Benedictine monasteries in Bavaria were suppressed, with the exception of that of St. James of the Scotts at Ratisbon, and of the Benedictine nuns at Eichstadt. In 1827, thanks to the influence of King Louis, the abbey of St. Michael’s at Wetten, and several other monasteries were restored. When it was proposed to found a seminary for the German missions in America, the Benedictines warmly entered into the project, and Father Boniface Wimmer, having offered to begin the work, was sent out by the Society of the Missions at Munich.

The first Benedictine monastery in the United States was founded at Latrobe, Pa., and dedicated to St. Vincent. By brief of July 29, 1855, it was raised to the dignity of abbey, according to the statutes of the Congregation of Bavaria, with Father Boniface Wimmer as first Mitred Abbot. It is at present the head of the American Cassinese congregation. A very flourishing college is attached to St. Vincent’s Abbey.1) Abbot Wimmer was afterwards appointed Arch-abbot. He died at Latrobe, Pa., December 8th, 1887. The congregation of which he was President has spread over the United States, and besides the abbeys of St. Vincent’s, Latrobe, Pa.; Atchison, Kansas; Newark, New Jersey; St. John’s Abbey, Collegeville, Minnesota, and Mary Help Abbey at Belmont, North Carolina, it possesses priories and stations in the dioceses of Baltimore, Chicago, New Orleans, New York, Oregon City, St. Paul, Covington, Davenport, Denver, Erie, Little Rock, Manchester, Mobile, Savannah, and St. Augustine.

St. Meinrad’s Abbey in the diocese of Vincennes, Indiana, is a filiation of the celebrated Abbey of Our Lady at Einsiedeln, Switzerland, and it belongs to the Swiss congregation.

After the Society of Jesus, the Benedictine order is the most numerous religious body in the United States. Though ages have passed over its head, it seems now in a period of rejuvenescence, and the venerable institution of St. Benedict is once more animated with youthful vigor.

In 1853 there was established at St. Marystown, in the diocese of Erie, a convent of Benedictine nuns from the abbey of St. Walburga at Eichstadt, in Bavaria, which dates as far back as the year 1022. At present Sisters of this order exist in many places in this country. They devote themselves to the education of girls, and direct parish schools and female academies. 2)

1) The Catholic Church in the United States.- De Courcy.- Shea.

2) Cath. Church in the U. S.- De Courcy.- Shea.

Source: History of religious orders. A compendious and popular sketch of the rise and progress of the principal monastic, canonical, military, mendicant, and clerical orders and congregations of the Eastern and Western churches, together with a brief history of the Catholic church in relation to religious orders by Charles Warren Currier. New York, Murphy & McCarthy, 1894.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.