BRAMSHILL HAMPSHIRE. Bramshill House is a Jacobean-style manor house located in Bramshill, in the northeastern county of Hampshire, United Kingdom. It is one of the largest castles in England from the time of its construction in the early 17th century. Construction period was from 1605 to 1612.

BRAMSHILL HOUSE is one of the most perfect of the remaining mansions of the time of James the First. It is said to have been erected for the excellent Prince Henry by whom it was never inhabited, his death having occurred before the building was completely finished. It became the property of the Lords Zouch, from whom it subsequently passed to the family of Cope the present proprietor being Sir John Cope, Bart.

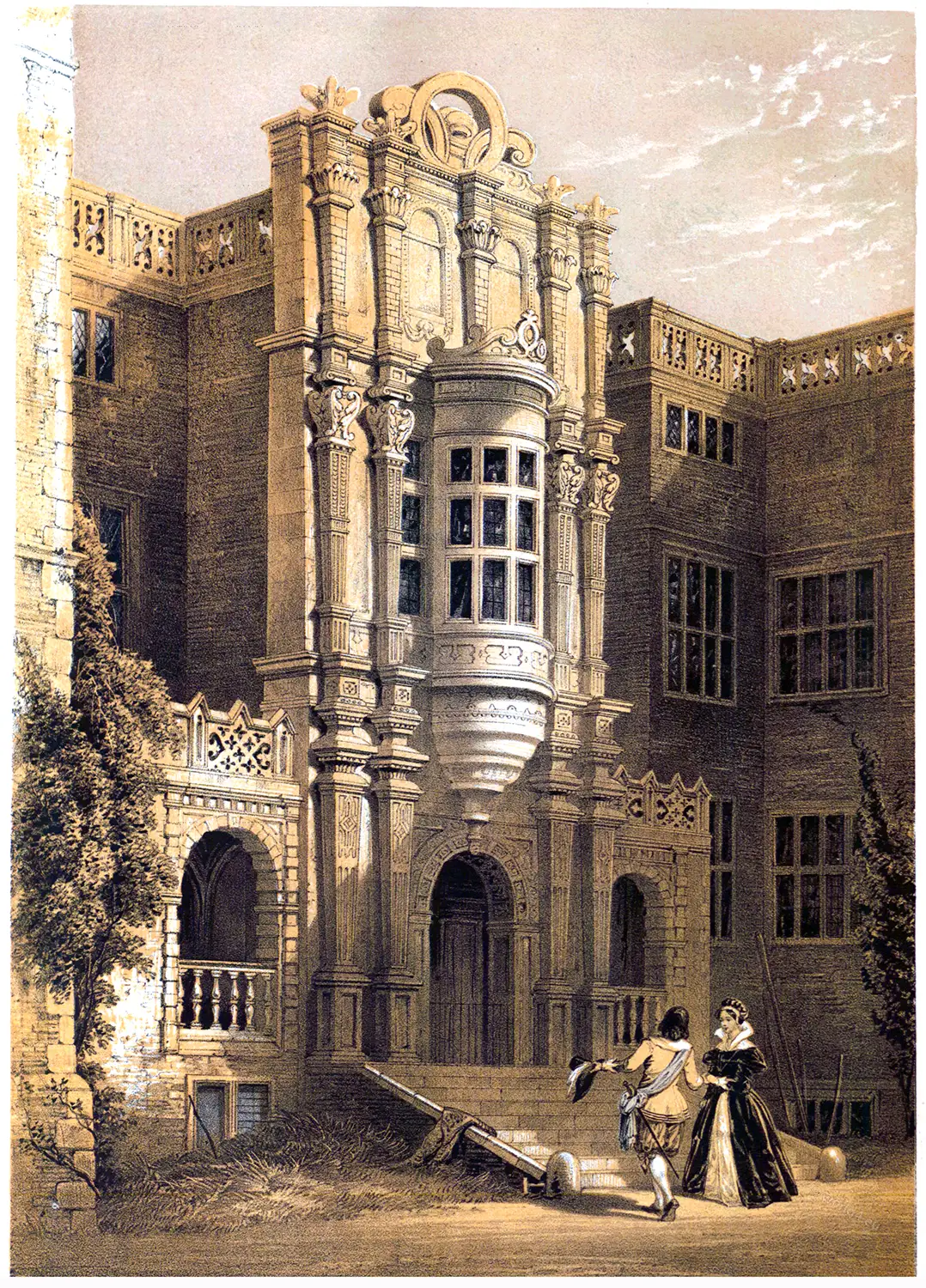

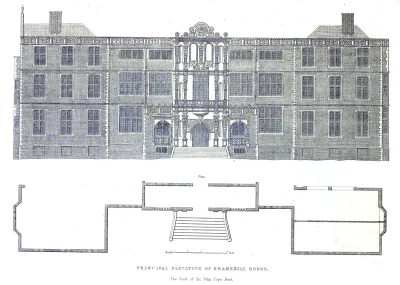

The wings are comparatively plain, constructed of brick, with stone dressings; but the centre is elaborately built of stone, finely carved and profusely decorated. It supplies a striking example of the peculiar architecture of the period, when “Italian improvements” were earliest introduced into, and mixed up with, our “old Gothic manner.” This central portion of the structure is carried up in rich compartments, with pilasters, from story to story, surmounted by a pediment of the same character, which bears the coronet of the Prince for whom the building is said to have been designed.

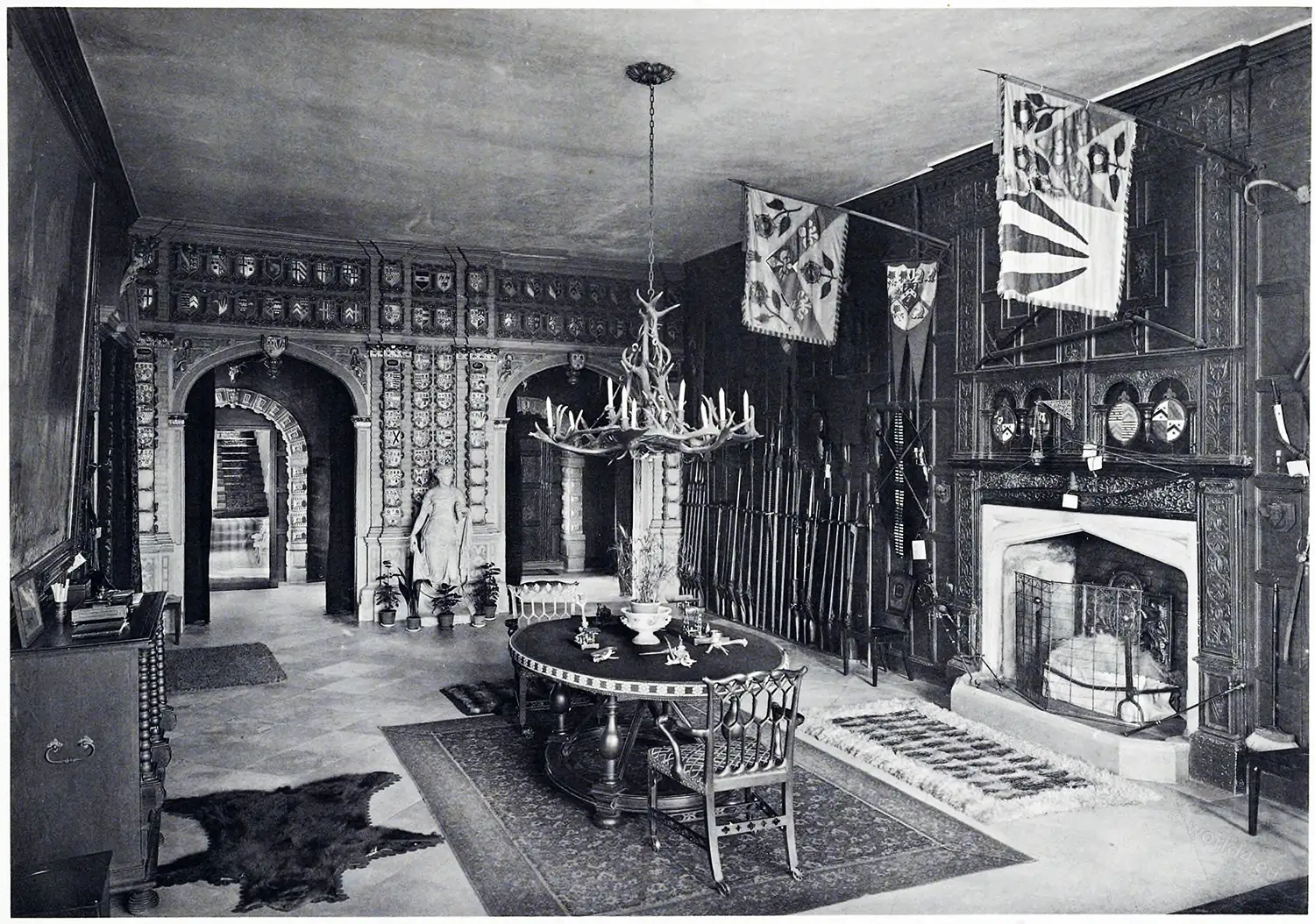

The interior is even more primitive and unimpaired than the exterior. The old Hall is floored and wainscotted with oak; the ceiling is enriched, and the walls are hung with family portraits in antique frames, in admirable keeping with the staid and solemn aspect of the venerable structure.

The apartments throughout the mansion are of the same interesting class. In the principal drawing-room, the needle rivals the pencil upon the tapestried walls; every chamber retains unaltered its ancient character: the furniture and “garnishing” are of other days; the massive fire-places still afford space for the hospitable yule log; and in the chairs and couches that throng the several apartments, we see the quaint and elaborate carvings and embroidered coverings which exhibit the skill and industry of gone-by times. All things within the mansion are in harmony with the impressive grandeur it derives from age. Circumstances have happily existed to prevent the coarse assaults of the modern Renovator; and Bramshill House remains and, we hope, will long continue a fine example of the period of its erection.

Such “Houses” are rarely encountered now-a-days a mansion so little altered, within and without, that Imagination may readily recall its ancient peopling the long galleries, shadowed recesses, and spacious Hall, with the formal and stately Dames and Knights of the period when it was erected. There are, indeed, few places that are so easily associated with the past; one might almost fancy that the very chairs and tables have been unmoved during two whole centuries.

The House is auspiciously situated: it stands on rising ground, and commands extensive prospects of the surrounding country. It has recently obtained augmented importance in consequence of the visit of Her Majesty, Queen Victoria, who, while a guest of his Grace the Duke of Wellington, examined the old mansion of Bramshill, which is distant about six miles from Strathfieldsaye.

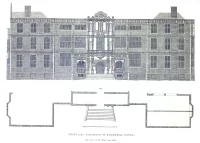

Plate XXIX.

The principal Elevation of Bramshill House, in Hampshire, the Seat of Sir John Cope, Bart. Date 1603.

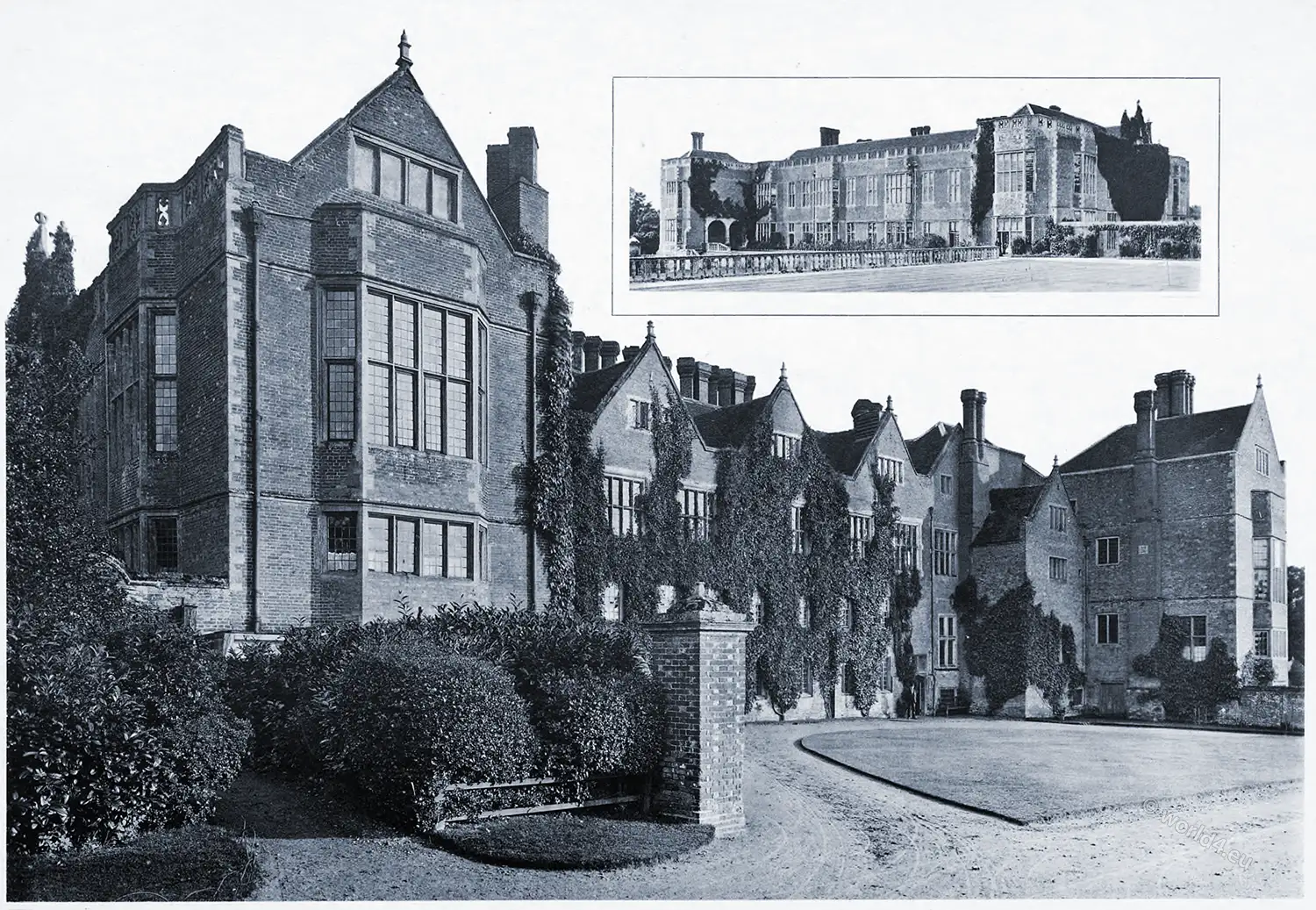

Bramshill House is in the parish of Eversley, on the borders of Berkshire and Surrey, at a short distance from Hartford Bridge: its situation is open and commanding, and as a specimen of Elizabethan architecture, merits particular attention, exhibiting all the stateliness for which the period referred to was remarkable, with a suite of apartments both large and lofty.

The amplitude of its dimensions indicate a princely residence, and it is traditionally reported to have been erected for the highly accomplished and amiable Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, the eldest son of King James I., who died at the age of eighteen, in the year 1612. Bramshill House was the residence of Edward, Lord Zoucli, of Harringworth, a nobleman highly favoured by King James, who appointed him Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, and Constable of Dover Castle.

Bramshill Park is not large, but there is an historical anecdote con- nected withit, which gives the spot some interest. Dr.George Abbot, Archbishop of Canterbury, who took an active part in all the great transactions of state, when in a declining state of health, used in the summer to retire into Hampshire for the sake of recreation, and had accepted an invitation from Lord Zouch to hunt the fallow deer in his park at Bramshill. During the enjoyment of his sport, he one’ day accidentally killed that nobleman’s keeper by an arrow from a cross-bow, which he had aimed at one of the herd. This misfortune threw the Archbishop into a deep melancholy, and the prelate ever afterwards kept a monthly fast on Tuesday, the day on which this fatal accident happened.

The Archbishop’s conduct was submitted to inquiry,but it did not lessen him in the King’s favour, who observed, “that an angel might have miscarried in this sort,” and accordingly his Majesty granted him pardon, and declared him still capable of all the authority of a primate.

In the reign of Charles I. Bramshill House was partly destroyed by fire, a circumstance which is noticed by Fuller. In 1673, it was the residence of Sir Andrew Henley, Bart., but has been for a considerable time the property of the family of the present possessor, one of which built the mansion at Kensington, now called Holland House.

Plate XXX.

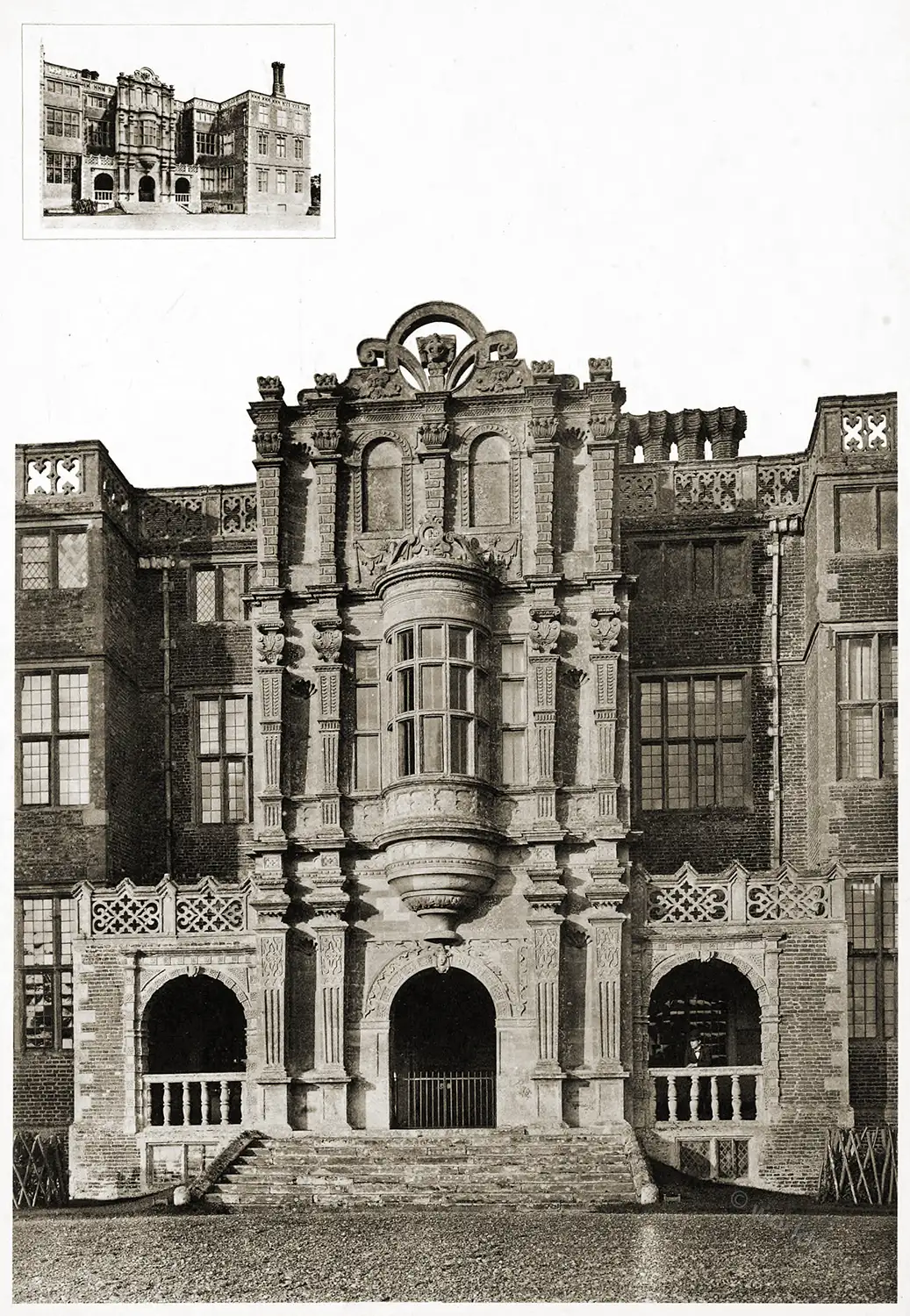

The Oriel Window in the Western Elevation of Bramshill House, in Hampshire. Date 1603.

In the architecture of Bramshill House, is to be observed the attempt at Italian improvement, then newly introduced. The mainbuilding, three stories in heightand about one hundred and forty feet in extent, is constructed with brick, with stone dressings to the numerous large and lofty windows the; quoins also are of stone, and the whole is surmounted by an open carved parapet of the same material. The central compartment of the principal front, about twenty feet in width, is built wholly with stone, and displays a profusion of ornamental decoration, including the very fine Oriel Window shown on the Plate. This portion of the building, an interesting architectural specimen, is carried up with terminal pilasters of the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian style, from story to story, and is surmounted by a florid pediment which is perforated.

The Oriel, or compas Window, in the centre of the front, is singularly beautiful in design, with much lightness and elegance in its details. This species of window is one of the most ornamental features in the exterior of a building, and equally cheerful in the interior. In the instance here given, the beauty of its proportions renders it an example particularly worthy of attention.

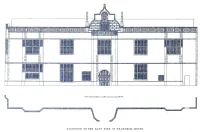

Plate XXXI.

The Elevation of the Eastern Side of Bramshill House, in Hampshire. Date 1603.

This front towards the east, exhibits comparatively little ornament, but shows that general uni- formity in design was preserved, even although it was necessary for internal convenience to vary the situation and size of particular windows.

In the centre of this front is a bold projection, in which is the arch of entrance, and above it a bay window. This projection, like the rest of the building, is crowned with an ornamental pierced parapet, and the whole is surmounted by a large gable, containing a recessed niche and statue of King James I.

This front is about one hundred and twenty-four feet in extent, and two stories in height.

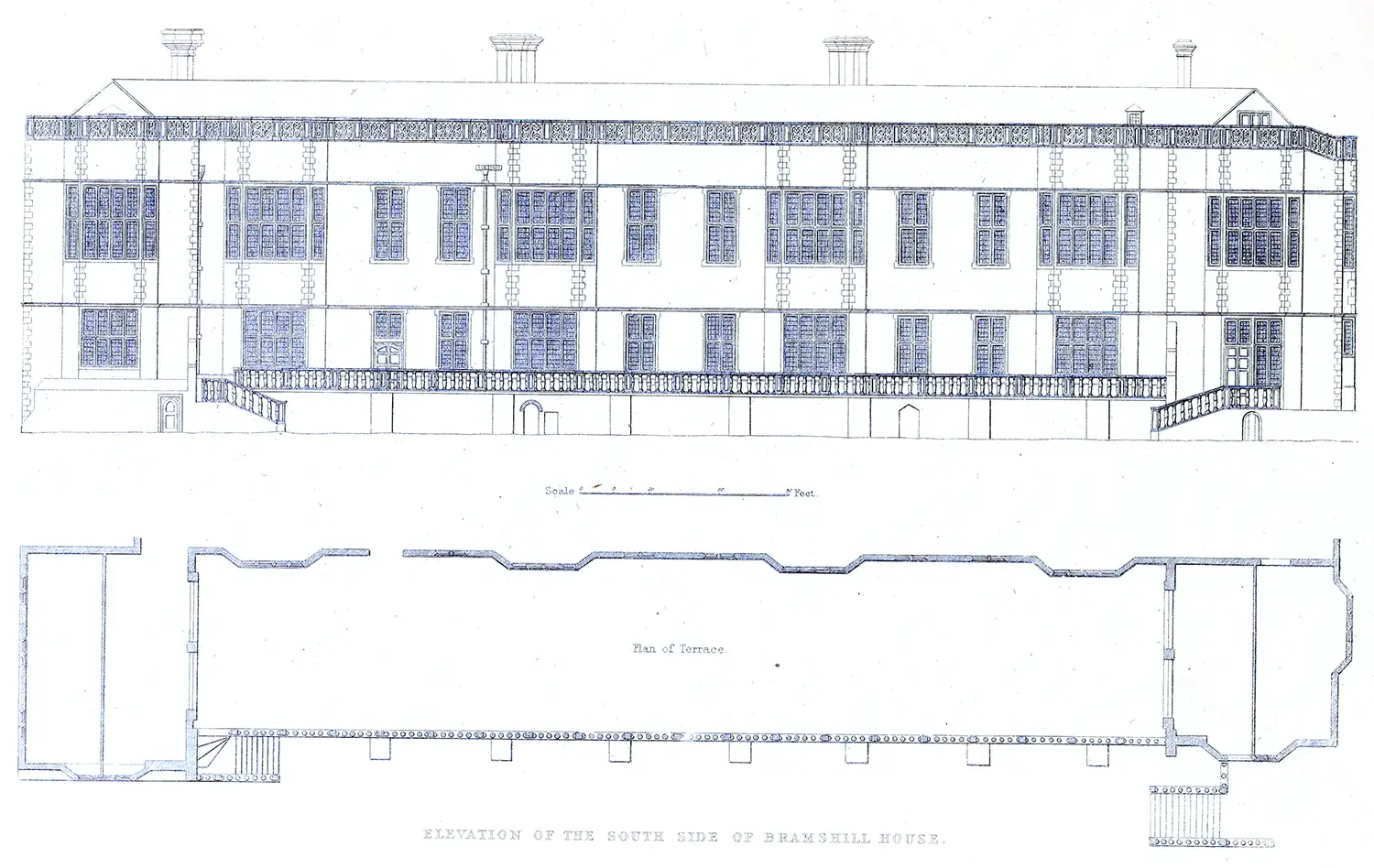

Plate XXXII.

The Elevation of the Southern Side of Bramshill House, in Hampshire. Date 1603.

The extent of this front is about one hundred and ninety-three feet, and in height, to the top of the parapet, forty-six feet: its principal feature, and most important difference from the other fronts of this noble building, is a terrace twenty-five feet in width between the projecting wings, a kind of architectural fore-ground to the garden, which is extremely beautiful. The terrace is bounded by a balustrade, and the general effect is very striking.

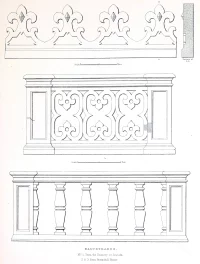

Plate XXXIII.

Balustrades, from the Deanery at Lincoln, and from Bramshill House. Date 1603.

The first subject of this Plate is a very beautiful crest or ornamental parapet of the Deanery House at Lincoln, rising three feet above the building, constructed about the same period as Bramshill House.

The second example shown is the pierced parapet, which crowns the whole of the house at Bramshill. The height of the parapet is three feet seven inches, and the small piers, about fourteen inches in width, are about four feet five inches distant from each other: the effect of the pierced work between them is very fine: a more light and elegant parapet is rarely found, even in the compositions of the best Italian architects.

The parapet, a great improvement to the elevation, is an architectural feature that in the Elizabethan era was much varied, but for simplicity of design it would be difficult to produce a finer instance.

The balusters of the terrace at Bramshill, which form the remaining example, are excellent in their proportions, and well adapted to the purpose for which they are applied. The height of the balustrade is three feet three inches.

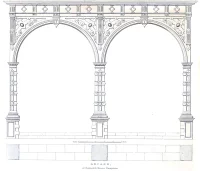

Plate XXXIV.

The Arcade at Bramshill House, in Hampshire. Date 1603.

The Arcade on the terrace of the southern front is here shown : it is a feature of domestic architecture, borrowed from Italy, where the terrace answered the purpose of exercise, and became an important accessory to every villa. In the present design, it may be objected by the classical architect that the imposts of the arches rest upon the pillars, and convey an appearance of instability. This idea has been combated by Mr. Woods, in his “Letters of an Architect,” who admits that the judgment does not easily reconcile itself to arches upon columns or on posts, for a column is only an ornamented stone post, but he confesses that there is a delightful lightness and airiness of effect produced by the distribution, difficult to be obtained by other means.

The enrichments of the arcade at Bramshill are extremely pleasing. The order intended is Doric but in this instance it is made; to assume all the lightness of the Ionic: metopes, together with the simple capitals of the columns, are the only distinctions by which the identity of the order is determined.

Plate XXXV.

The Stone Screen in the Hall at Bramshill House in Hampshire. Date 1603.

The Screen, at the lower end of the ancient halls, was a necessary arrangement, to mask the entrances from the offices, and much embellishment was usually lavished upon it. In ruder times it was customary to inscribe this part of the mansion with notices of invitation and welcome to the hospitality then ostentatiously exhibited; as at Halnaker House, in Sussex, now belonging to the Duke of Richmond, where the doors are labelled with the words, “Le BienVenue,” and “Come in and drinke,” coarsely carved.

The screen at Bramshill bears numerous shields, seemingly intended for emblazonment of the arms of the neighbouring gentry, who might be welcome to the spread of good cheer inseparable from the domestic establishment of a large mansion.

The simple inscription at Montacute House, in Somersetshire, “And yours, my friends,” answered the same benevolent purpose as the emblazoned frieze at Gilling Castle, where the members of every division of the county of York are separately distinguished by their family insignia.

The height of the screen in the hall at Bramshill is thirteen feet, and the depth of the entablature, containing a double row of sculptured shields, is two feet six inches. In the spandrils of the arches are introduced small female figures, one in each, emblematical of Justice and Wisdom, Industry and Plenty. The order intended in this enriched portion of the hall is Corinthian; but the architectural features are so modified by the exuberance of decoration as to be scarcely perceptible.

A section of the Screen is given on the same Plate, by which its relative thickness may be determined; and in the details the arabesque ornaments of the sculptured shields are shown at large.

Plate XXXVI.

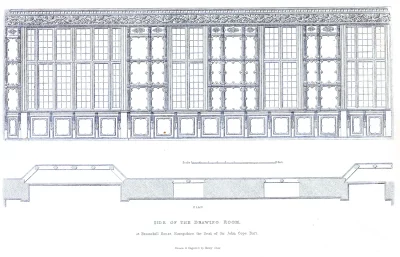

The side of the Drawing-room at Bramshill House, in Hampshire. Date 1603.

In the mansions of our old nobility, the next room, in point of importance to the hall, was the guest- chamber, into which the company retired, sometimes called the drawing-room, a name abbreviated from withdrawing room: the phrase is generally supposed to be of more modern date but in the age of Elizabeth, Whetstone, in his Heptameron says, “The queene sent for the chosen company who were placed in the drawinge chamber”: proving the use of the term, even before the torrent of puritanical zeal had subdued ancient splendour, and French taste had been introduced in the reign of Charles II.

The drawing-room at Bramshill is lighted by four bay windows of different sizes; and to its whole height, about sixteen feet, is panelled with oak, the ribs or styles being carved, and the surface of the panel left plain. The frieze is a beautiful design of a running pattern of foliage and fruit, which is shown at large on the next Plate, together with the mouldings and size of the panels. The richness occasioned by the variations from uniformity of surface in these large rooms is very striking.

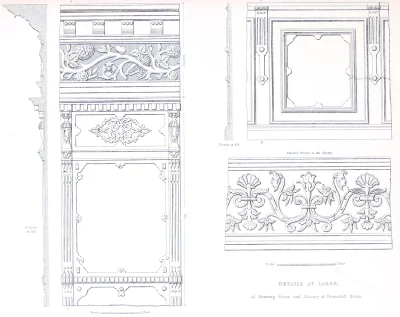

Plate XXXVII.

The Details at large of the Drawing-room and Library at Bramshill House, Hampshire. Date 1603.

The first subject of this Plate is one of the upper panels of the Drawing-room, surmounted by its beautiful Corinthian entablature, in the frieze of which are introduced the fig, the grape, and the pomegranate, each with its appropriate foliage and blossoms the architrave rests on; dentils, and the frieze is overshadowed by a bold modillioned cornice slightly enriched with carving.

One of the lower panels, part of the dado in the same room, is also shown on this Plate, with a section of the projecting mouldings. The upper panel is two feet ten inches, by two feet four inches in dimension the lower, two feet seven inches, by two feet six inches.

The plaster frieze in the Library, of a very elegant arabesque pattern, quite in the Florentine taste, is nineteen inches in width. The workmanship is excellent, and shows the great perfection the art of plastering had attained.

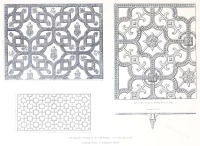

Plate XXXVIII.

Ceilings at Bramshill House, in Hampshire. Date 1603.

The Ceilings at Bramshill are not less characteristic of the Elizabethan period than the other architectural parts of the mansion; those of the old Library and Drawing-room have been selected as excellent examples, and it is not often that such fine specimens have been preserved.

The designs, which afford a pleasing variety, are so well arranged, that but little of the plain surface is left, and the compositions, abundantly ornamented, are managed with all the skill necessary to produce a light and elegant effect.

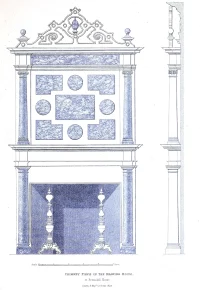

Plate XXXIX.

The Chimney-piece in the Drawing-room at Bramshill House, in Hampshire. Date 1603.

The massive appearance of this Chimney-piece is not injudiciously contrasted with the lighter panelling and richly worked ceiling of the same apartment: it is altogether executed in a more solid and less ornamental style of art. The design is classical, and after the manner of Vignola: it comprehends two stories in height; the lower being Doric, and the upper Ionic.

The distribution of the members is pure and regular columns, with their capitals and entablature, are well suited to each other, and the whole is surmounted by a sculptured pediment, which rises to the cornice of the room. The shafts of the columns are of variegated marble; and the upper compartment of the Chimney-piece is composed of separate pieces of the same diversified material, disposed in a manner rather formal, over the surface.

The frieze of the upper order is also formed of coloured marble in the centre ; and over the columns, the entablature is broken, which considerably relieves the effect, and preserves the appearance of solidity produced by the bold relief given to the several parts. The basement seems almost too low for the order above it. The fire-place, six feet in width, is four feet eight inches high, and retains the ancient andirons, or dogs, used for burning wood: these are of the larger sort, and are much ornamented, particularly at the lower part. A profile of the projection of the Chimney-piece is shown on the Plate.

See also:

- Hall of Boughton-Malherbe, County of Kent. Elizabethan England 16th c..

- Wilton House. The manor house is home to the Earls of Pembroke.

Source:

- The baronial halls, and ancient picturesque edifices of England. From drawings by J.D. Harding, G. Cattermole, S. Prout, W. M, by Samuel Carter Hall, (1800-1889). London, Chapman and Hall, 1858.

- Monuments in Great Britain by Constantin Uhde. Berlin, E. Wasmuth, 1894.

- Source: Details of Elizabethan architecture by Henry Shaw (1800-1873; Thomas Moule (1784-1851). London: W. Pickering, 1839.

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.