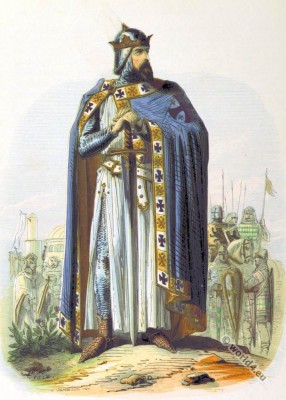

KING RICHARD AND THE THIRD CRUSADE.

THE Crusades were the mightiest or rather the most ambitions undertaking of the chivalry of Europe. From the year 1096 for more than a century the knights of all countries looked to the Holy Land as a field for winning their spurs and obtaining pardon of their sins. And it is most natural that in giving a picture of English chivalry as it is shown in history that we should give a description of King Richard’s exploits in Palestine.

In the last decade of the twelfth century Richard I. of England took the cross, which had come to him as a sort of legacy from his father, and sailed for Antioch, which was being besieged by the Christians, to assist in the war in the Holy Land.

At the same time Philip Augustus of France and Frederick Barbarossa joined the Crusaders. Frederick was drowned in a river of Cilicia, and his force had so dwindled that when they reached Antioch hardly a tenth of the number were left that had started. Philip II of France reached Antioch with his army, and there, as we shall learn later, he fought with the Turk and quarrelled with the Christian for a time, until he finally set sail for France without having accomplished the capture of the Holy City.

As for Richard, he was not more successful, and although his deeds were so glorious as to cover him with honour, he was obliged to return home, leaving Jerusalem *) still in the hands of infidels.

*) The Kingdom of Jerusalem was one of four Crusader states in the Holy Land. It existed from 1099 to 1291.

The Exploits of King Richard I.

On a crusade undertaken together with Philip, now counted as the Third Crusade, Richard conquered Cyprus in 1191. He then crossed over to the Holy Land, where he successfully ended the siege of Acre, which had already lasted two years.

Now as the ships were proceeding, some being before others, two of the three first, driven by the violence of the winds, were broken on the rocks near the port of Cyprus; the third, which was English, more speedy than they, having turned back into the deep, escaped the peril. Almost all the men of both ships got away alive to land, many of whom the hostile Cypriotes slew, some they took captive, some, taking refuge in a certain church, were besieged. Whatever also in the ships was cast up by the sea fell a prey to the Cypriotes.

The prince also of that island coming up, received for his share the gold and the arms; and he caused the shore to be guarded by all the armed force he could summon together, that he might not permit the fleet which followed to approach, lest the king should take again what had been thus stolen from him.

Above the port was a strong city, and upon a natural rock, a high and fortified castle. The whole of that nation was warlike and accustomed to live by theft. They placed beams and planks at the entrance of the port, across the passage, the gates, and entrances; and the whole land with one mind prepared themselves for a conflict with the English.

God so willed that the cursed people should receive the reward of their evil deeds by the hands of one who would not spare. The third English ship, in which were the women, having cast out their anchors, rode out at sea, and watched all things from opposite, to report the misfortunes to the king,*) lest haply, being ignorant of the loss and disgrace, he should pass the place unavenged.

The next line of the king’s ships came up after the other, and they are stopped at the first. A full report reached the king, who, sending heralds to the lord of the island, and obtaining no satisfaction, commanded his entire army to arm, from the first even to the last, and to get out of the great ships into the galleys and boats, and follow him to the shore.

What he commanded was immediately performed; they came in arms to the port. The king being armed, leaped first from the galley, and gave the first blow in the war; but before he was able to strike a second he had three thousand of his followers with him striking away at his side. All the timber that had been placed as a barricade in the port was cast down instantly, and the brave fellows went up into the city as ferocious as lionesses are wont to be when robbed of their young. The fight was carried on manfully against them, numbers fell wounded on both sides, and the swords of both parties were made drunk with blood.

The Cypriotes are vanquished, the city is taken, with the castle besides; whatever the victors choose is ransacked; and the lord of the island is himself taken and brought to the king. He being taken, supplicates and obtains pardon; he offers homage to the king, and it is received; and he swears, though unasked, that henceforth he will hold the island of him as his liege lord, and will open all the castles of the land to him, and make satisfaction for the damage already done; and further bring presents of his own. On being dismissed after the oath, he is commanded to fulfil the conditions in the morning.

That night the king remained peaceably in the castle; and his newly sworn vassal, flying, retired to another castle, and caused the whole of the men of the land, who were able to bear arms, to be summoned to repair to him, and so they did. The king of Jerusalem, however, that same night landed in Cyprus, that he might assist the king and salute him, whose arrival he had desired above that of any other in the whole world. On the morrow the lord of Cyprus was sought for-and found to have fled.

The king seeing that he was abused, and having been informed where he was, directed the king of Jerusalem to follow the traitor by land with the best of the army, while he conducted the other part by water, intending to be in the way that he might not escape by sea. The divisions reassembled around the city in which he had taken refuge, and he, having sallied out against the king, fought with the English, and the battle was carried on sharply by both sides.

The English would that day have been beaten had they not fought under the command of King Richard. They at length obtained a dear-bought victory, the Cypriote flies, and the castle is taken. The kings pursue him as before, the one by land and the other by water, and he is besieged in the third castle. Its walls are cast down by engines hurling huge stones; he, being overcome, promises to surrender, if only he might not be put in iron fetters. The king consents to the prayers of the supplicant, and caused silver shackles to be made for him.

The prince of the pirates being thus taken, the king traversed the whole island, and took all its castles, and placed his constables in each, and constituted justiciaries and sheriffs, and the whole land was subjected to him in everything just like England. The gold, and the silks and the jewels from the treasuries that were broken open, he retained for himself; the silver and victuals he gave to the army. To the king of Jerusalem also he made a handsome present out of the booty.

The king proceeding thence, came to the siege of Acre, and was welcomed by the besiegers with as great a joy as if it had been Christ that had come again on earth to restore the kingdom of Israel. The king of the French had arrived at Acre first, and was very highly esteemed by the natives; but on Richard’s arrival he became obscured and without consideration, just as the moon is wont to relinquish her lustre at the rising of the sun.

The king of the English, unused to delay, on the third day of his arrival at the siege, caused his wooden fortress, which he had called “Mate Grifun,” when it was made in Sicily, to be built and set up, and before the dawn of the fourth day the machine stood erect by the walls of Acre, and from its height looked down upon the city lying beneath it; and there were thereon by sunrise archers casting missiles without intermission on the Turks and Thracians. Engines also for casting stones, placed in convenient positions, battered the walls with frequent volleys. More important than these, the sappers, making themselves a way beneath the ground, undermined the foundations of the walls; while soldiers, bearing shields, having planted ladders, sought an entrance over the ramparts.

The king himself was running up and down through the ranks, directing some, reproving some, and urging others, and thus was he everywhere present with every one of them, so that whatever they all did ought properly to be ascribed to him. The king of the French also did not lightly assail them, making as bold an assault as he could on the tower of the city which is called Cursed.

The renowned Carracois and Mestocus, after Saladin, the most powerful princes of the heathen, had at that time the charge of the besieged city, who, after a contest of many days, promised by their interpreters the surrender of the city, and a ransom for their heads; but the king of the English desired to subdue their obstinacy by force ; and wished that the vanquished should pay their heads for the ransom of their bodies, but by the mediation of the king of the French their life and indemnity of limbs only was accorded, if, after the surrender of the city and yielding of everything they possessed, the Holy Cross should be given up.

All the heathen warriors in Acre were chosen men, and were in number nine thousand; many of whom, swallowing many gold coins, made a purse of their stomachs, because they foresaw that whatever they had of any value would be turned against them, even against themselves, if they should again oppose the cross, and would only fall a prey to the victors. So all of them came out before the kings entirely disarmed, and outside the city, without money, were given into custody; and the kings, with triumphal banners, having entered the city, divided the whole with all its stores into two parts between themselves and their soldiers; the pontiff’s seat alone its bishop received by their united gift. The captives, being divided, Mestocus fell by lot to the portion of the king of the English, and Carracois, as a drop of cold water, fell into the mouth of the thirsty Philip, king of the French.

Messengers on the part of the captives having been sent to Saladin for their ransom, when the heathen could by no entreaty be moved to restore the Holy Cross, the king of the English beheaded all his, with the exception of Mestocus only, who on account of his nobility was spared, and declared openly, without any ceremony, that he would act in the same way toward Saladin himself.

The king of the English, then, having sent for the commanders of the French, proposed that in the first place they should conjointly attempt Jerusalem itself; but the dissuasion of the French discouraged the hearts of both parties, dispirited the troops, and restrained the king, thus destitute of men, from his intended march on that metropolis. The king, troubled at this, though not despairing, from that day forth separated his army from the French, and directing his arms to the storming of castles along the seashore, he took every fortress that came in his way from Tyre to Ascalon, though after hard fighting and deep wounds.*)

*) The preceding narrative is taken from the Chronicle of Richard of Devizes; english chronicler, monk of St Swithin’s house at Winchester. What follows is from the Chronicle of Geoffrey de Vinsauf. Geoffrey of Vinsauf (also Galfridus, Gaufredus, Gaufridus, Godefridus, Ganfredus; surname de Vinosalvo, Vinesauf, Anglicus; Anglo-Norman Geoffroi de Vinsauf) was an English rhetorician of the late 12th century whose Poetria nova was one of the most influential poetry doctrines of the Middle Ages.

On the Saturday, the eve of the Nativity of the blessed Virgin Mary, at earliest dawn, our men armed themselves with great care to receive the Turks, who were known to have preceded their march, and whose insolence nothing but a battle could check. The enemy had ranged themselves in order, drawing gradually nearer and nearer; and our men also took the utmost care to place themselves in as good order as possible.

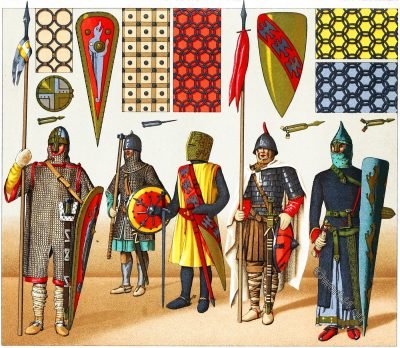

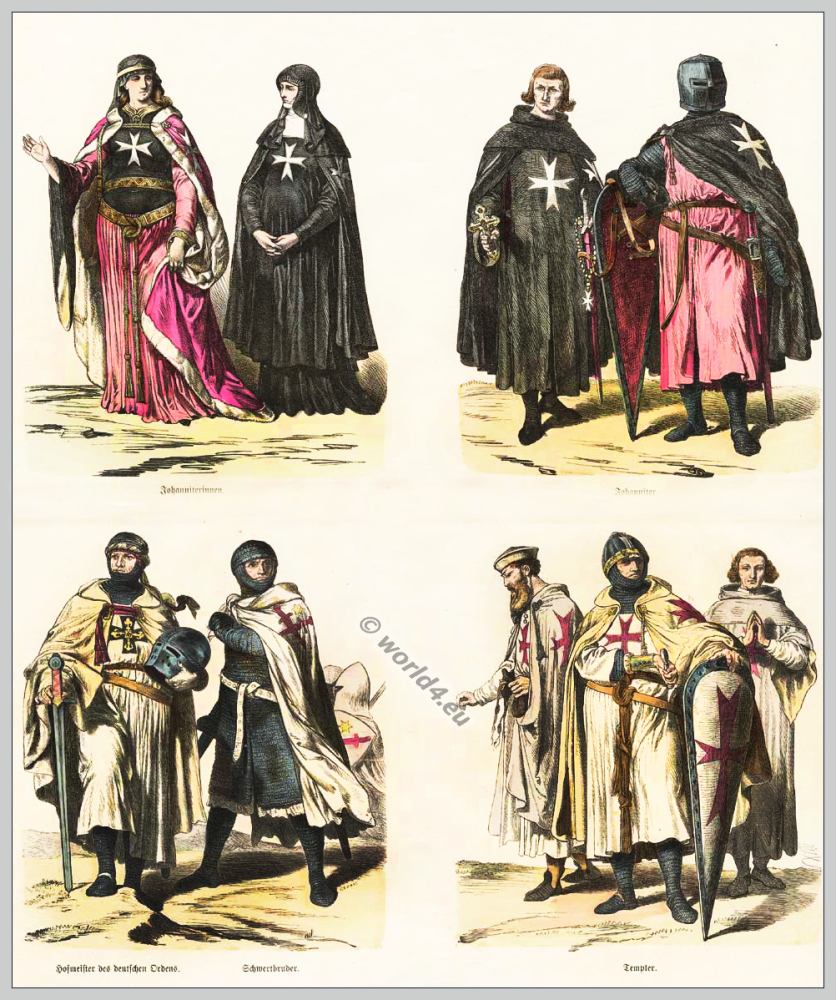

King Richard, who was most experienced in military affairs, arranged the army in squadrons, and directed who should march in front and who in the rear. He divided the army into twelve companies, and these again into five divisions, marshalled according as the men ranked in military discipline; and none could be found more warlike, if they had only had confidence in God, who is the giver of all good things. On that day the Templars formed the first rank, and after them came, in due order, the Bretons and men of Anjou; then followed King Guy, with the men of Pictou; and in the fourth line were the Normans and English, who had the care of the royal standard, and last of all marched the Hospitallers: this line was composed of chosen warriors, divided into companies.

They kept together so closely that an apple, if thrown, would not have fallen to the ground without touching a man or a horse; and the army stretched from the army of Saracens to the seashore. There you might have seen their most appropriate distinctions,- standards, and ensigns of various forms, and hardy soldiers, fresh and full of spirits, and well fitted for war. Henry, Count of Champagne, kept guard on the mountain side, and maintained a constant lookout on the flank; the foot-soldiers, bowmen, and arbalesters were on the outside, and the rear of the army was closed by the post horses and wagons, which carried provisions and other things, and journeyed along between the army and the sea, to avoid an attack from the enemy.

This was the order of the army, as it advanced gradually, to prevent separation; for the less close the line of battle, the less effective was it for resistance. King Richard and the Duke of Burgundy, with a chosen retinue of warriors, rode up and down, narrowly watching the position and manner of the Turks, to correct anything in their own troops, if they saw occasion, for they had need, at that moment, of the utmost circumspection.

It was now nearly nine o’clock, when there appeared a large body of the Turks, ten thousand strong, coming down upon us at full charge, and throwing darts and arrows as far as they could, while they mingled their voices in one horrible yell. There followed after them an infernal race of men, of black color, and bearing a suitable appellation, expressive of their blackness.

With them also were the Saracens, who live in the desert, called Bedouins; they are a savage race of men, blacker than soot; they fight on foot, and carry a bow, quiver, and round shield, and are a light and active race.

These men dauntlessly attacked our army. Beyond these might be seen the well-arranged phalanxes of the Turks, with ensigns fixed to their lances, and standards and banners of separate distinctions. Their army was divided into troops, and the troops into companies, and their numbers seemed to exceed twenty thousand. They came on with irresistible charge, on horses swifter than eagles, and urged on like lightning to attack our men; and as they advanced they raised a cloud of dust, so that the air was darkened.

In front came certain of their admirals, as it was their duty, with clarions and trumpets; some had horns, others had pipes and timbrels, gongs, cymbals, and other instruments, producing a horrible noise and clamor. The earth vibrated from the loud and discordant sounds, so that the crash of thunder could not be heard amidst the tumultuous noise of horns and trumpets. They did this to excite their spirit and courage, for the more violent their clamor became, the more bold were they for the fray.

Thus the impious Turks threatened us, both on the side towards the sea and from the side of the land; and for the space of two miles not so much earth as could be taken up in one hand could be seen, on account of the hostile Turks who covered it. Oh, how obstinately they pressed on, and continued their stubborn attacks, so that our men suffered severe loss of their horses, which were killed by their darts and arrows. Oh, how useful to us on that day were our arbalesters *) and bowmen, who closed the extremities of the lines, and did their best to repel the obstinate Turks.

*) The arbalest (also called arbalst) was a model of crossbow used in the late Middle Ages. This crossbow was a slightly larger version of the wooden crossbow already used in the early Middle Ages, with the difference that in the Arbalest the actual bow was made of steel.

The enemy came rushing down, like a torrent, to the attack; and many of our arbalesters, unable to restrain the weight of their terrible and calamitous charge, threw away their arms, and, fearing lest they should be shut out, took refuge, in crowds, behind the dense lines of the army; yielding through fear of death to sufferings which they could not support. Those whom shame forbade to yield, or the hope of an immortal crown sustained, were animated with greater boldness and courage to persevere in the contest, and fought with indefatigable valor face to face against the Turks, whilst they at the same time receded step by step, and so reached their retreat. The whole of that day, on account of the Turks pressing them closely from behind, they faced around and went on skirmishing, rather than proceeding on their march.

Oh, how great was the strait they were in on that day! how great was their tribulation! when some were affected with fears, and no one had such confidence or spirit as not to wish, at that moment, he had finished his pilgrimage, and, had returned home, instead of standing with trembling heart the chances of a doubtful battle. In truth our people, so few in number, were so hemmed in by the multitudes of the Saracens, that they had no means of escape, if they tried; neither did they seem to have valor sufficient to withstand so many foes,-nay, they were shut in like a flock of sheep in the jaws of wolves, with nothing but the sky above, and the enemy all around them.

O Lord God! What feelings agitated that weak flock of Christ! Straitened by such a perplexity, whom the enemy pressed with such unabating vigor, as if they would pass them through a sieve. What army was ever assailed by so mighty a force? There you might have seen our troopers, having lost their chargers, marching on foot with the footmen, or casting missiles from the arbalests, or arrows from bows, against the enemy, and repelling their attacks in the best manner they were able.

The Turks, skilled in the bow, pressed unceasingly upon them; it rained darts; the air was filled with the shower of arrows, and the brightness of the sun was obscured by the multitude of missiles, as if it had been darkened by a fall of winter’s hail or snow. Our horses were pierced by the darts and arrows, which were so numerous that the whole face of the earth around was covered with them, and if any one wished to gather them up, he might take twenty of them in his hand at a time.

The Turks pressed with such boldness that they nearly crushed the Hospitallers; on which the latter sent word to King Richard that they could not withstand the violence of the enemy’s attack, unless he would allow their knights to advance at full charge against them. This the king dissuaded them from doing, but advised them to keep in a close body; they therefore persevered and kept together, though scarcely able to breathe for the pressure. By these means they were able to proceed on their way, though the heat happened to be very great on that day; so that they laboured under two disadvantages,- the hot weather and the attacks of the enemy.

These approved martyrs of Christ sweated in the contest; and he who could have seen them closed up in a narrow space, so patient under the heat and toil of the day and the attacks of the enemy, who exhorted each other to destroy the Christians, could not doubt in his mind that it augured ill to our success from their straitened and perilous position, hemmed in as they were by so large a multitude; for the enemy thundered at their backs as if with mallets, so that, having no room to use their bows, they fought hand to hand with swords, lances, and clubs, and the blows of the Turks, echoing from their metal armour, resounded as if they had been struck upon an anvil.

They were now tormented with the heat, and no rest was allowed them. The battle fell heavy on the extreme line of the Hospitallers, the more so as they were unable to resist, but moved forward with patience under their wounds, returning not even a word for the blows which fell upon them, and advancing on their way because they were not able to bear the weight of the contest.

Then they pressed on for safety upon the centre of the army which was in front of them, to avoid the fury of the enemy who harassed them in the rear. Was it wonderful that no one could withstand so continuous an attack, when he could not even return a blow to the numbers who pressed on him? The strength of all Paganism had gathered together from Damascus and Persia, from the Mediterranean to the East; there was not left in the uttermost recesses of the earth one man of fame or power, one nation’s valour, or one bold soldier, whom the sultan had not summoned to his aid, either by entreaty, by money, or by authority, to crush the Christian race; for he presumed to hope he could blot them from the face of the earth; but his hopes were vain, for their numbers were sufficient, through the assistance of God, to effect their purpose.

The flower of the chosen youth and soldiers of Christendom had indeed assembled together, and were united in one body, like ears of corn on their stalks, from every region of the earth; and if they had been utterly destroyed, there is no doubt that there were some left to make resistance.

A cloud of dust obscured the air as our men marched on; and, in addition to the heat, they had an enemy pressing them in the rear, insolent, and rendered obstinate by the instigation of the devil. Still the Christians proved good men, and secure in their unconquerable spirit, kept constantly advancing, while the Turks threatened them without ceasing in the rear; but their blows fell harmless upon the defensive armour, and this caused the Turks to slacken in courage at the failure of their attempts, and they began to murmur in whispers of disappointment, crying out in their rage, “that our people were made of iron and would yield to no blow.”

Then the Turks, about twenty-thousand strong, rushed again upon our men pell-mell, annoying them in every possible manner; when, as if overcome by their savage fury, brother Garnier de Napes, one of the Hospitallers, suddenly exclaimed with a loud voice, “O excellent St. George! will you leave us to be thus put to confusion? The whole of Christendom is now on the point of perishing, because it fears to return a blow against this impious race.”

Upon this the master of the Hospitallers went to the king, and said to him, “My lord the king, we are violently pressed by the enemy, and are in danger of eternal infamy, as if we did not dare to return their blows; we are each of us losing our horses one after another, and why should we bear with them any further?” To whom the king replied, “Good master, it is you who must sustain their attack; no one can be everywhere at once.”

On the master returning, the Turks again made a fierce attack on them from the rear, and there was not a prince or count amongst them but blushed with shame, and they said to each other, “Why do we not charge them at full gallop? Alas! Alas! we shall forever deserve to be called cowards, a thing which never happened to us before, for never has such a disgrace befallen so great an army, even from unbelievers. Unless we defend ourselves by immediately charging the enemy we shall gain everlasting scandal, and so much the greater the longer we delay to fight.” O, how blind is human fate! On what slippery points it stands! Alas, on how uncertain wheels doth it advance, and with what ambiguous success doth it unfold the course of human things!

A countless multitude of the Turks would have perished if the aforesaid attempt had been orderly conducted; but to punish us for our sins, as it is believed, the potter’s ware produces a paltry vessel instead of the grand design which he had conceived. For when they were treating on this point, and had come to the same decision about charging the enemy, two knights, who were impatient of delay, put everything in confusion.

It had been resolved by common consent that the sounding of six trumpets in three different parts of the army should be a signal for a charge, viz., two in front, two in the rear, and two in the middle, to distinguish the sounds from those of the Saracens, and to mark the distance of each. If these orders had been attended to, the Turks would have been utterly discomfited; but from the too great haste of the aforesaid knights the success of the affair was marred.

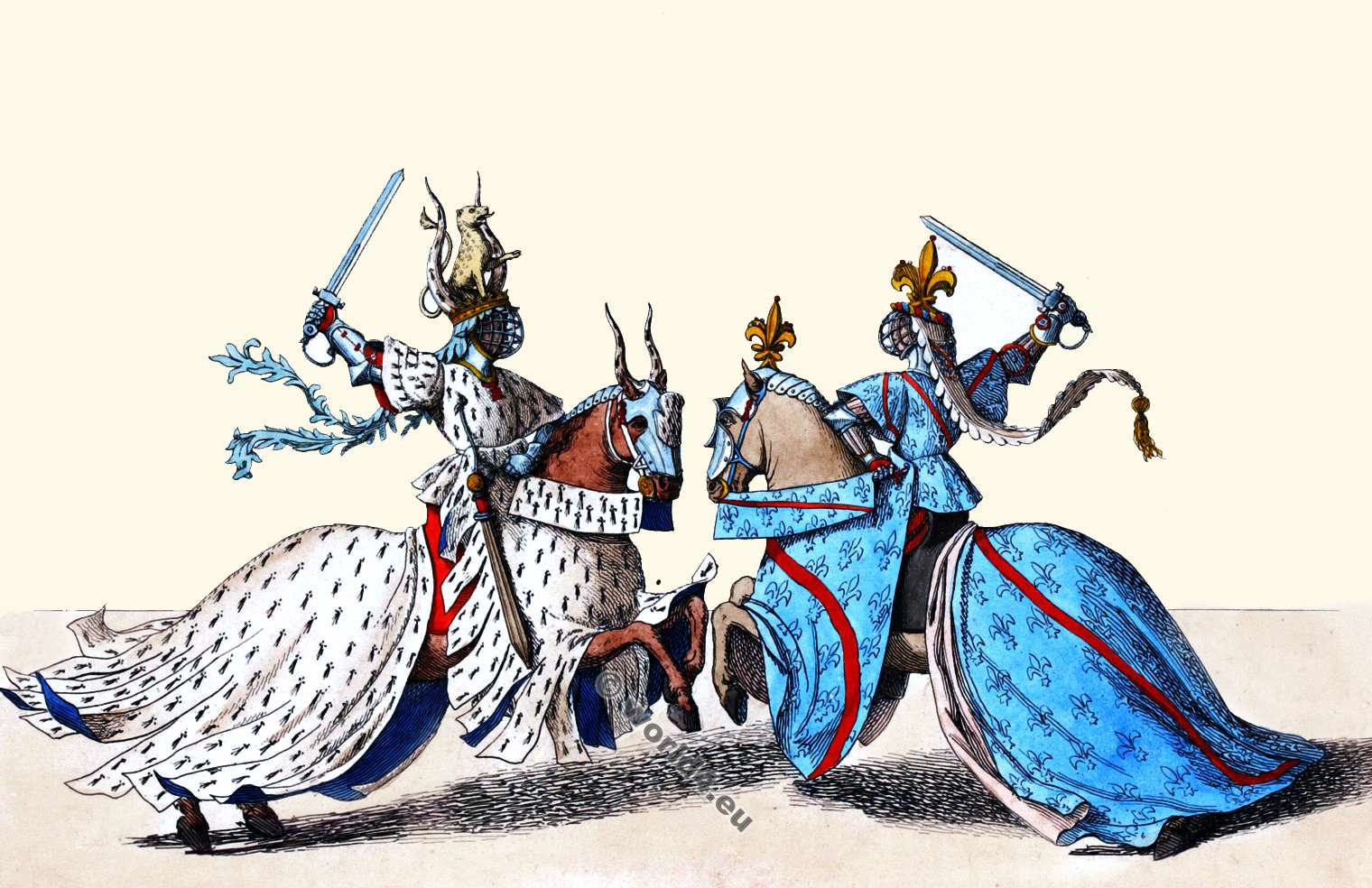

They rushed at full gallop upon the Turks, and each of them prostrated his man by piercing him through with his lance. One of them was the marshal of the Hospitallers, the other was Baldwin de Carreo, Knight of Hospitaller, a good and brave man, and the companion of King Richard, who had brought him in his retinue. When the other Christians observed these two rushing forward, and heard them calling with a clear voice on St. George for aid, they charged the Turks in a body with all their strength; then the Hospitallers, who had been distressed all day by their close array, following the two soldiers, charged the enemy in troops, so that the van of the army became the rear from their position in the attack, and the Hospitallers, who had been the last, were the first to charge.

The Count of Champagne also burst forward with his chosen company, and James d’Avennes with his kinsmen, and also Robert Count of Dreux, the bishop of Beauvais and his brother, as well as the Earl of Leicester, who made a fierce charge on the left towards the sea.

Why need we name each? Those who were in the first line of the rear made a united and furious charge; after them the men of Poictou, the Bretons, and the men of Anjou, rushed swiftly onward, and then came the rest of the army in a body: each troop showed its valor, and boldly closed with the Turks, transfixing them with their lances, and casting them to the ground. The sky grew black with the dust that was raised in the confusion of that encounter.

The Turks, who had purposely dismounted from their horses in order to take better aim at our men with their darts and arrows, were slain on all sides in that charge, for on being prostrated by the horse-soldiers they were beheaded by the foot-men. King Richard, on seeing his army in motion and in encounter with the Turks, flew rapidly on his horse at full speed through the Hospitallers, who had led the charge, and to whom he was bringing assistance with all his retinue, and broke into the Turkish infantry, who were astonished at his blows and those of his men, and gave way to the right and to the left.

Then might be seen numbers prostrated on the ground, horses without their riders in crowds, the wounded lamenting with groans their hard fate, and others drawing their last breath, weltering in their gore, and many lay headless, whilst their lifeless forms were trodden under foot both by friend and foe. Oh, how different are the speculations of those who meditate amidst the columns of the cloister from the fearful exercise of war!

There the king, the fierce, the extraordinary king, cut down the Turks in every direction, and none could escape the force of his arm, for wherever he turned, brandishing his sword, he carved a wide path for himself; and as he advanced and gave repeated strokes with his sword, cutting them down like a reaper with his sickle, the rest, warned by the sight of the dying, gave him more ample space, for the corpses of the dead Turks which lay on the face of the earth extended over half a mile.

In fine, the Turks were cut down, the saddles emptied of their riders, and the dust which was raised by the conflict of the combatants proved very hurtful to our men, for on becoming fatigued from slaying so many, when they were retiring to take fresh air, they could not recognise each other on account of the thick dust, and struck their blows indiscriminately to the right and to the left; so that unable to distinguish friend from foe they took their own men for enemies and cut them down without mercy.

Then the Christians pressed hard on the Turks, the latter gave way before them: but for a long time the battle was doubtful; they still exchanged blows, and either party strove for the victory; on both sides were seen some retreating, covered with wounds, while others fell slain to the ground.

Oh, how many banners and standards of different forms, and pennons and many-coloured ensigns, might there be seen torn and fallen on the earth; swords of proved steel, and lances made of cane with iron heads, Turkish bows, and maces bristling with sharp teeth, darts and arrows covering the ground, and missiles enough to load twenty wagons or more!

There lay the headless trunks of the Turks who had perished, whilst others retained their courage for a time until our men increased in strength, when some of them concealed themselves in the copses, some climbed up trees, and, being shot with arrows, fell with a fearful groan to the earth; others, abandoning their horses, betook themselves by slippery footpaths to the seaside, and tumbled headlong into the waves from the precipitous cliffs that were five poles in height.

The rest of the enemy were repulsed in so wonderful a manner that for the space of two miles nothing could be seen but fugitives, although they had before been so obstinate and fierce, and puffed up with pride; but by God’s grace their pride was humbled, and they continued still to fly, for when our men ceased the pursuit fear alone added wings to their feet.

Our army had been ranged in divisions when they attacked the Turks; the Normans and English also, who had the care of the standard, came up slowly towards the troops which were fighting with the Turks,-for it was very difficult to disperse the enemy’s strength, and they stopped at a short distance therefrom, that all might have a rallying point. On the conclusion of the slaughter our men paused; but the fugitives, to the number of twenty-thousand, when they saw this, immediately recovering their courage, and armed with maces, charged the hindmost of those who were retiring, and rescued some from our men who had, just struck them down.

Oh, how dreadfully were our men then pressed! for the darts and arrows, thrown at them as they were falling back, broke the heads, arms, and other limbs of our horsemen, so that they bent, stunned, to their saddle-bows; but having quickly regained their spirits and resumed their strength, and thirsting for vengeance with greater eagerness, like a lioness when her whelps are stolen, they charged the enemy, and broke through them like a net.

Then you might have seen the horses with their saddles displaced, and the Turks, who had but just now fled, returning, and pressing upon our people with the utmost fury; every cast of their darts would have told had our men kept marching, and not stood still in a compact, immovable body.

The commander of the Turks was an admiral, named Tekedmus, a kinsman of the sultan, having a banner with a remarkable device; namely that of a pair of breeches carved thereon, a symbol well known to his men. He was a most cruel persecutor, and a persevering enemy of the Christians; and he had under his command seven hundred chosen Turks of great valour, of the household troops of Saladin, each of whose companies bore a yellow banner with pennons of a different color.

These men, coming at full charge, with clamor and haughty bearing, attacked our men, who were turning off from them towards the standard, cutting at them, and piercing them severely, so that even the firmness of our chiefs wavered under the weight of the pressure; yet our men remained immovable, compelled to repel force by force.

And the conflict grew thicker, the blows were redoubled, and the battle waxed fiercer than before: the one side laboured to crush, the other to repel; both exerted their strength, and although our men were by far the fewest in numbers, they made havoc of great multitudes of the enemy; and that portion of the army which thus toiled in the battle could not return to the standard with ease, on account of the immense mass which pressed upon them so severely; for thus hemmed in they began to flag in courage, and but few dared to renew the attack of the enemy.

In truth, the Turks were furious in the assault, and greatly distressed our men, whose blood poured forth in a stream beneath their blows. On perceiving them reel and give way, William de Barris, a renowned knight, breaking through the ranks, charged the Turks with his men; and such was the vigour of the onset that some fell by the edge of his sword, while others only saved themselves by rapid flight.

For all that, the king, mounted on a bay Cyprian steed, which had not its match, bounded forward in the direction of the mountains, and scattered those he met on all sides; for the enemy fled from his sword and gave way, while helmets tottered beneath it, and sparks flew forth from its strokes.

So great was the fury of his onset, and so many and deadly his blows that day, in his conflict with the Turks, that in a short space of time the enemy were all scattered, and allowed our army to proceed; and thus our men, having suffered somewhat, at last returned to the standard, and proceeded on their march as far as Arsur,*) and there they pitched their tents outside its walls.

*) Arsuf was an ancient city and later Crusader city and Crusader fortress in present-day Israel, about 15 kilometers north of Tel Aviv. In 1101, the city was occupied by a Crusader army under Balduin I of Jerusalem. The Crusaders, who mostly called the city Arsur in their sources, rebuilt the city walls and created the dominion of Arsuf within the Kingdom of Jerusalem. The dominion initially belonged to the crown domain of the King of Jerusalem, until he enfeoffed John of Arsur with the dominion in 1163. When John died childless, Melisende, the daughter of his brother Guido, took over the dominion. Through Melisende’s second marriage to John of Ibelin, Lord of Beirut (1177-1236), Arsuf passed to the Ibelin family in 1207. Their son John of Arsuf († 1258) inherited the dominion, which he passed on to his eldest son Balian († 1277). In 1260 or 1261 Balian sold the dominion to the Order of St. John. In 1187, the city was conquered by the Muslim Ayyubids under Sultan Saladin, but fell back to the Christians after the Battle of Arsuf on September 7, 1191 between Richard the Lionheart and Saladin. In 1265, Arsuf was conquered by the Muslim Mamluk Sultan Baibars I. The walls and fortress were razed, and the population dispersed.

While they were thus engaged a large body of the Turks made an attack on the extreme rear of our army. On hearing the noise of the assailants, King Richard, encouraging his men to battle, rushed at full speed, with only fifteen companions, against the Turks, crying out, with a loud voice, “Aid us, O God! and the Holy Sepulchre!” and this he exclaimed a second and a third time; and when our men heard it they made haste to follow him, and attacked, routed, and put them to flight; pursuing them as far as Arsur, whence they had first come out, cutting them down and subduing them. Many of the Turks fell there also.

The king returned thence from the slaughter of the fugitives to his camp; and the men, overcome with the fatigue and exertions of the day, rested quietly that night.

Whoever was greedy of gain, and wished to plunder the booty, returned to the place of battle, and loaded himself to his heart’s desire; and those who returned from thence reported that they had counted thirty-two Turkish chiefs who were found slain on that day, and whom they supposed to be men of great influence and power from the splendour of their armour and the costliness of their apparel.

The Turks also made search for them to carry them away as being of the most importance; and besides these the Turks carried off seven thousand mangled bodies of those who were next in rank, besides of the wounded, who went off in straggling parties; and when their strength failed lay about the fields and died.

But by the protection of God we did not lose a tenth, nor a hundredth part so many as fell in the Turkish army. Oh, the disasters of that day! Oh, the trials of the warriors! for the tribulations of the just are many. Oh, mournful calamity and bitter distress. How great must have been the blackness of our sins to require so fiery an ordeal to purify it, for if we had striven to overcome the urgent necessity by pious long-suffering, and without a murmur, the sense of our obligations would have been deeper.

And again the Christians were put in great peril, in the following manner. At the siege of Joppa a certain depraved set of men among the Saracens, called Menelones of Aleppo and Cordivi, an active race, met together to consult what should be done in the existing state of things. They spoke of the scandal which lay against them, that so small an army, without horses, had driven them out of Joppa, and they reproached themselves with cowardice and shameful baseness, and arrogantly made a compact among themselves that they would seize King Richard in his tent, and bring him before Saladin, from whom they would receive a most munificent reward.

So they prepared themselves in the middle of the night to surprise the king, and sallied forth armed, by the light of the moon, conversing with one another about the object they had in hand. Oh, hateful race of unbelievers! They are anxiously bent upon seizing Christ’s steadfast soldier while he is asleep. They rush on in numbers to seize him, unarmed and apprehensive of no danger.

They were not far from his tent, and were preparing to lay hands on him, when, lo! the God of mercy, who never neglects those who trust in Him, and acts in a wonderful manner even to those who know Him not, sent the spirit of discord among the aforesaid Cordivi and Menelones.

The Cordivi said, “You shall go in on foot to take the king and his followers, whilst we will remain on horseback to prevent their escaping into the castle.” But the Menelones replied, “Nay, it is your place to go in on foot, because our rank is higher than yours; but this service on foot belongs to you rather than us.” Whilst thus the two parties were contending which of them were the greatest, their combined dispute caused much delay; and when at last they came to a decision how their nefarious attempt should be achieved, the dawn of the day appeared, viz., the Wednesday next following the feast of St. Peter ad vincula.

But now by the providence of God, who had decreed that his holy champion should not be seized whilst asleep by the infidels, a certain Genoese was led by the divine impulse to go out early in the morning into the fields, where he was alarmed by the noise of men and horses advancing, and returned speedily, but just had time to see helmets reflecting back the light which now fell upon them. He immediately rushed with speed into the camp, calling out, “To arms! to arms!” The king was awakened by the noise, and leaping startled from his bed, put on his impenetrable coat of mail, and summoned his men to the rescue.

God of all mercies! Lives there a man who would not be shaken by such a sudden alarm? The enemy rushed unawares, armed against unarmed, many against few, for our men had no time to arm or even to dress themselves. The king himself, therefore, and many others with him, on the urgency of the moment, proceeded without their cuishes to the fight, some even without their breeches, and they armed themselves in the best manner they could, though they were going to fight the whole day.

Whilst our men were thus arming in haste, the Turks drew near, and the king mounted his horse, with only ten other knights with him. These alone had horses, and some even of them had base and impotent horses, unused to arms; the common men were drawn skilfully out in ranks and troops, with each a captain to command them.

The knights were posted nearer to the sea, having the church of St. Nicholas on the left, because the Turks had directed their principal attack on that quarter, and the Pisans and Genoese were posted beyond the suburban gardens, having other troops mingled with them. Oh, who could fully relate the terrible attacks of the infidels? The Turks at first rushed on with horrid yells, hurling their javelins and shooting their arrows.

Our men prepared themselves as they best could to receive their furious attack, each fixing his right knee in the ground, that so they might the better hold together and maintain their position; whilst there the thighs of their left legs were bent, and their left hands held their shields or bucklers; stretched out before them in their right hands they held their lances, of which the lower ends were fixed in the ground, and their iron heads pointed threateningly towards the enemy.

Between every two of the men who were thus covered with their shields, the king, versed in arms, placed an arbalester, and another behind him to stretch the arbalest as quickly as possible, so that the man in front might discharge his shot whilst the other was loading.

This was found to be of much benefit to our men, and did much harm to the enemy. Thus everything was prepared as well as the shortness of the time allowed, and our little army was drawn up in order. The king ran along the ranks, and exhorted every man to be brave and not to flinch.

“Courage, my brave men,” said he; “and let not the attack of the enemy disturb you. Bear up against the powers of fortune, and you will rise above them. Everything may be borne by brave men; adversity sheds a light upon the virtues of mankind. as certainly as prosperity casts over them a shade; there is no room for flight, for the enemy surround us, and to attempt to flee is to provoke certain death. Be brave, therefore, and let the urgency of the case sharpen up your valor; brave men should either conquer nobly or gloriously die.

Martyrdom is a boon which we should receive with willing mind; but before we die, let us, whilst still alive, do what we may to avenge our deaths, giving thanks to God that it has been our lot to die martyrs. This will be the end of our labors, the termination of our life and of our battles. These words were hardly spoken, when the hostile army rushed with ferocity upon them, in seven troops, each of which contained about a thousand horse. Our men received their attack with their right feet planted firm against the sand, and remained immovable. Their lances formed a wall against the enemy, who would have assuredly broken through, if our men had in the least given way.

The first line of the Turks, perceiving, as they advanced, that our men stood immovable, recoiled a little, when our men plied them with a shower of missiles, slaying large numbers of men and horses. Another line of Turks at once came on in like manner, and were again encountered and driven back. In this way the Turks came on like a whirlwind, again and again, making the appearance of an attack, that our men might be induced to give way, and when they were close up they turned their horses off in another direction.

The king and his knights, who were on horseback, perceiving this, put spurs to their horses, and charged into the middle of the enemy, upsetting them right and left, and piercing a large number through the body with their lances; at last they pulled up their horses, because they found that they had penetrated entirely through the Turkish lines.

The king, now looking about him, saw the noble earl of Leicester fallen from his horse, and fighting bravely on foot. No sooner did he see this, than he rushed to his rescue, snatched him out of the hands of the enemy, and replaced him on his horse. What a terrible combat was then waged! A multitude of Turks advanced, and used every exertion to destroy our small army; vexed at our success, they rushed toward the royal standard of the lion, for they would rather have slain the king than a thousand others.

In the midst of the mêlée ((fr. = the tumult, the melee, mixed) the king saw Ralph de Mauleon dragged off prisoner by the Turks, and spurring his horse to speed, in a moment released him from their hands, and restored him to the army; for the king was a very giant in the battle, and was everywhere in the field,-now here, now there, wherever the attacks of the Turks raged the hottest. So bravely did he fight, that there was no one, however gallant, that would not readily and deservedly yield to him the pre-eminence. On that day he performed the most gallant deeds on the furious army of the Turks, and slew numbers with his sword, which shone like lightning; some of them were cloven in two, from their helmet to their teeth, whilst others lost their heads, arms, and other members, which were lopped off at a single blow.

While the king was thus laboring with incredible exertions in the fight, a Turk advanced towards him, mounted on a foaming steed. He had been sent by Saphadin of Archadia, brother to Saladin, a liberal and munificent man, if he had not rejected the Christian faith. This man now sent to the king, as a token of his well-known honorable character, two nobles horses, requesting him earnestly to accept them, and make use of them, and if he returned safe and sound out of that battle, to remember the gift and recompense it in any manner he pleased.

The king readily received the present, and afterwards nobly recompensed the giver. Such is bravery, cognizable even in an enemy; since a Turk, who was our bitter foe, thus honored the king for his distinguished valor. The king, especially at such a moment of need, protested that he would have taken any number of horses equally good from any one even more a foe than Saphadin, so necessary were they to him at that moment.

Fierce now raged the fight, when such numbers attacked so few; the whole earth was covered with the javelins and arrows of the unbelievers; they threw them, several at a time, at our men, of whom many were wounded. Thus the weight of battle fell heavier up on us than before, and the galley-men withdrew in the galleys which brought them; and so, in their anxiety to be safe, they sacrificed their character for bravery.

Meanwhile a shout was raised by the Turks, as they strove who should first occupy the town, hoping to slay those of our men whom they should find within. The king, hearing the clamor, taking with him only two knights and two crossbow-men, met three Turks, nobly caparisoned, in one of the principal streets. Rushing bravely upon them, he slew the riders in his own royal fashion, and made booty of two horses. The rest of the Turks who were found in the town were put to the rout in spite of their resistance, and dispersing in different directions, sought to make their escape, even where there was no regular road. The king also commanded the parts of the walls which were broken down to be made good, and placed sentinels to keep watch lest the town should be again attacked.

These matters settled, the king went down to the shore, where many of our men had taken refuge on board the galleys. These the king exhorted by the most cogent arguments to return to the battle, and share with the rest whatever might befall them. Leaving five men as guards on board each galley, the king led back the rest to assist his hard-pressed army, and he no sooner arrived than with all his fury he fell upon the thickest ranks of the enemy, driving them back and routing them, so that even those who were at a distance and untouched by him were overwhelmed by the throng of the troops as they retreated. Never was there such an attack made by an individual. He pierced into the middle of the hostile army, and performed the deeds of a brave and distinguished warrior.

The Turks at once closed upon him, and tried to overwhelm him. In the meantime our men, losing sight of the king, were fearful lest he should have been slain, and when one of them proposed that they should advance to find him, our lines could hardly contain themselves. But if by any chance the disposition of our troops had been broken, without doubt they would all have been destroyed.

What, however, was to be thought of the king, who was hemmed in by the enemy, a single man opposed to so many thousands? The hand of the writer faints to see it, and the mind of the reader to hear it. Who ever heard of such a man? His bravery was ever of the highest order, no adverse storm could sink it; his valour was ever becoming, and if we may from a few instances judge of many, it was ever indefatigable in war.

Why then do we speak of the valour of Antaeus, who regained his strength every time he touched his mother earth, for Antaeus perished when he was lifted up from the earth in the long wrestling match. The body of Achilles also, who slew Hector, was invulnerable, because he was dipped in the Stygian waves; yet Achilles was mortally wounded in the very part by which he was held when they dipped him.

Likewise Alexander, the Macedonian, who was stimulated by ambition to subjugate the whole world, undertook a most difficult enterprise, and with a handful of choice soldiers fought many celebrated battles, but the chief part of his valor consisted of the excellence of his soldiers.

In the same manner the brave Judas Maccabeus, of whom all the world discoursed, performed many wonderful deeds worthy forever to be remembered, but when he was abandoned by his soldiers in the midst of a battle, with thousands of enemies to oppose him, he was slain, together with his brothers. But King Richard, inured to battle from his tenderest years, and to whom even famous Roland could not be considered equal, remained invincible, even in the midst of the enemy; and his body, as if it were made of brass, was impenetrable to any kind of weapon. In his right hand he brandished his sword, which in its rapid descent broke the ranks on either side of him.

Such was his energy amid that host of Turks that, fearing nothing, he destroyed all around him, mowing men down with his scythe as reapers mow down the corn with their sickles. Who could describe his deeds? Whoever felt one of his blows had no need of a second. Such was the energy of his courage that it seemed to rejoice at having found an occasion to display itself. The sword wielded by his powerful hand cut down men and horses alike, cleaving them to the middle. The more he was himself separated from his men, and the more the enemy sought to overwhelm him, the more did his valour shine conspicuous.

Among other brave deeds which he performed on that occasion he slew by one marvellous stroke an admiral, who was conspicuous above the rest of the enemy by his rich caparisons. This man by his gestures seemed to say that he was going to do something wonderful, and whilst he reproached the rest with cowardice he put spurs to his horse and charged full against the king, who, waving his sword as he saw him coming, smote off at a single blow not only his head, but his shoulder and right arm. The Turks were terror-struck at the sight, and, giving way on all sides, scarcely dared to shoot at him from a distance with their arrows.

The king now returned safe and unhurt to his friends, and encouraged them more than ever with the hope of victory. How were their minds raised from despair when they saw him coming safe out of the enemy’s ranks! They knew not what had happened to him, but they knew that without him all the hopes of the Christian army would be in vain.

The king’s person was stuck all over with javelins, like a deer pierced by the hunters, and the trappings of his horse were thickly covered with arrows. Thus, like a brave soldier, he returned from the contest, and a bitter contest it was, for it had lasted from the morning sun to the setting sun. It may seem wonderful and even incredible, that so small a body of men endured so long a conflict; but by God’s mercy we cannot doubt the truth of it, for in that battle only one or two of our men were slain. But the number of the Turkish horses that lay dead on the field is said to have exceeded fifteen hundred; and of the Turks themselves more than seven hundred were killed, and yet they did not carry back King Richard, as they had boasted, as a present to Saladin; but, on the contrary, he and his horse performed so many deeds of valour in the sight of the Turks that the enemy shuddered to behold him.

In the meantime our men having by God’s grace escaped destruction, the Turkish army returned to Saladin, who is said to have ridiculed them by asking where Melech Richard was, for they had promised to bring him a prisoner? “Which of you,” continued he “first seized him, and where is he? Why is he not produced?” To whom one of the Turks that came from the furthest countries of the earth replied, “In truth, my lord, Melech Richard, about whom you ask, is not here; we have never heard since the beginning of the world that there ever was such a knight, so brave and so experienced in arms. In every deed of arms he is ever the foremost; in deeds he is without a rival, the first to advance and the last to retreat; we did our best to seize him, but in vain, for no man can escape from his sword; his attack is dreadful; to engage with him is fatal, and his deeds are beyond human nature.”

Source: The age of chivalry; by Thomas Bulfinch (1796-1867); Edward Everett Hale (1822-1909). Boston, S. W. Tilton & co. [etc.]; New York, C. T. Dillingham, 1884.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.