Catalina de Erauso alias Francisco Loyola (* 1592 in Donostia-San Sebastián, Spain; † 1650 in Cuitlaxtla, New Spain, today Mexico) was a Basque noblewoman who lived as a man for several decades (“The nun lieutenant”).

Catalina de Erauso. The fighting nun lieutenant.

THE story of Catalina de Erauso, the Spanish nun who became famous as a soldier and fought with great courage in the wars in Chile and Peru in the 17th century, has been a theme of inspiration for several writers.

De Quincey described her adventurous career; it was dramatized in Spain, and her interesting story was told in Spanish verse by Jose Maria de Heredia in ‘La nonne alferez,’ and translated into French in 1894. She had the distinction of being promoted to the rank of ensign on the field and was the first woman to be granted permission by a Pope to wear masculine attire.

She is said to have been born in San Sebastian in 1592, her father being Captain don Miguel de Erauso and her mother Dona Maria Perez de Galarraga y Arce. At an early age she was sent to a convent of Dominican nuns to be educated. She had three brothers in the service of the State, Miguel, the eldest, being an officer in the Army.

After serving a year as a novice she was received into the community under the name of Catalina de Aliri. Later she fled from the convent, and, dressing herself as a man, she set off on her adventures. After serving as a page to Don Carlos de Arellano, a gallant soldier, she eventually made her way to Seville and enlisted in one of the galleons bound for the Spanish Main.

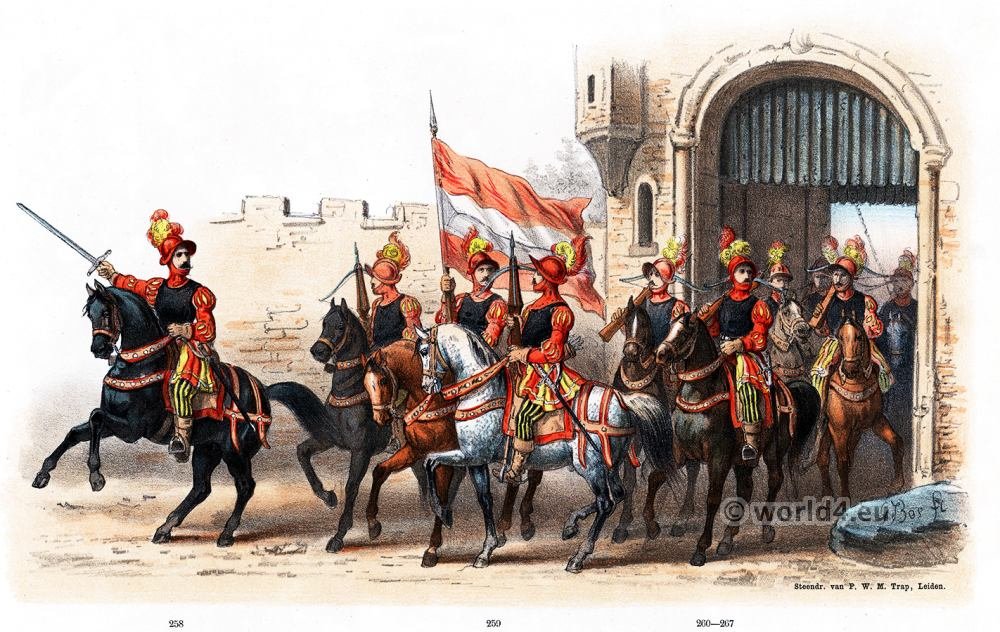

On landing she joined the army under the name of Alonso Diaz Ramérez de Guzman and served through the campaigns against tho Indians in Chile and Peru. She was under the command of Diego Braho de SarabÍa for over two years and afterwards was attached to the company of Captain Gonzalo Rodriguez, on whose recommendation she “vas promoted to the rank of ensign for distinguished service on the field.

She next served under Captain Guillén de Casanova, who commanded the garrison holding the fortress of Araoco, and was wounded at the battle of Puren. During the whole period of her service in Chile and Peru she preserved the secret of her sex and her disguise was never penetrated, not even by her brother, Ensign Miguel de Erauso, with whom she served unrecognized.

In action she was conspicuous for her courage and daring, while her gambling propensities involved her in many brawls and fights. In one of these, when she was severely wounded and lay in a serious condition, she disclosed the secret of her sex to the Bishop of Guamanga. This ended her career as a soldier, and under the name of Antonio de Erauso she returned to Europe in 1624. Such briefly is her story.

According to the narrative of her life written by herself, Catalina made up her mind to leave the convent after a quarrel and conflict with ‘ a brawny nun who laid violent hands’ on her. This she deeply resented, and she determined to escape from the community; while the nuns were rising from the midnight mass she managed to get hold of the convent keys and shut the doors of the building for the last time.

She had made no special plans as to the route she should take, so she took shelter in a grove of chestnut trees outside the town to consider what she should do next. The first thing was to disguise herself, and she decided to dress in men’s clothes in order to escape recognition.

She cut out and made herself a pair of breeches from a blue cloth skirt she was wearing and from her linsey petticoat she fashioned a doublet and garters. She then cut off her hair and, arraying herself in the male garments she had made, set out on the third night, skirting the villages and keeping to the roads. She at length reached Vitoria, having eaten nothing but the herbs she found by the wayside.

At Vitoria she sought refuge with a doctor named Don Francisade Cerralta, a professor who had married a first cousin of her mother’s. He treated her with kindness and gave her clothes, and during the three months she stayed with him he taught her Latin. When she made up her mind to leave him she borrowed some money from the doctor, obtained a lift in a carrier’s cart, and went to Valladolid, where she soon obtained employment as a page.

While there she heard that her father had come in search of her, but she did not see him, so quickly packing up her things and with but eight doubloons in her pocket she set out for Bilbao. Later she went on to Estelle where she got work as a page again, but soon left for Passage, where she boarded a ship sailing for Seville. There she enlisted as a boy on a galleon that formed part of the armada which had been fitted out for Punta de Araya, Caribbean, and sailed for America.

Landing at Panama she left the ship and took service with Captain Juan de Ibarra, Controller of the Treasury, and remained with him for three months. Then Catalina’s restless spirit asserted itself again; she met with a merchant of Trujillo called Juan de Urquiza, and sailed with him in a frigate bound for Paita, Peru.

There for a while she took charge of a shop for him, but in a brawl in which she was engaged she killed a man and afterwards fled to Lima. Now, having determined that fighting was her forte she enlisted as a private in one of the six companies recruited for service in Chile, to form an army of 1600 men.

Arrived at Concepción, Chile, she carne across her brother, whom she had never seen, as he had gone to America before she was born. When he heard she had come from his native province in Spain he became greatly interested in her and got her transferred to his company. She served under him for three years without disclosing her identity.

At Concepción she led the rollicking life of a soldier, and later marched out with the army to the plains of Valdivia to engage the Indians who had massed there, find inflicted severe losses on the Spaniards.

In one battle they attacked the ensign and captured the flag. Although wounded in the leg Catalina pursued them and with great bravery recaptured the flag and brought it back to the company. The Governor presented her with the flag she had saved and she was promoted to ensign in Alonso de Moreno’s company.

Catalina served as an ensign for five years and was present at the battle of Purén, where her captain was killed and the company put under her command. She led it for six months, during which period they had many encounters with the Indians, and she received several arrow wounds.

In one engagement she found herself in combat with a powerful Indian chief and unhorsed him in the fight; he surrendered, but Catalina lost her temper, and had him hanged from a tree. Through this action she got into trouble with the Governor, who ordered her back to Nacimiento.

Now in disgrace, she was involved in several quarrels, and then set out for Tucumán, Argentina, on foot. At length, nearly exhausted by fatigue and hunger, she was given shelter at the house of a wealthy Indo-Spanish woman who treated her with great kindness and asked her to remain on and manage her household.

This woman took a great liking to Catalina, and even wished her to marry her daughter, but she describes her as being ‘very black and as ugly as the devil.’ Catalina postponed the marriage under various pretexts until it became impossible for her to stay any longer, so she fled from her benefactor and the farm and went to Piscobamba, Peru.

She stayed the night at the house of a friend, and after supper one evening joined in a gambling gane with a Portuguese who was a great ruffian. Catalina won, but a quarrel arose and she dashed her cards in her opponent’s face. They both drew their rapiers, but the onlookers intervened and held them back, and eventually the Portuguese paid up his losses and calm was restored.

‘Three nights later,’ says Catalina, ‘at about eleven o’clock, when I was going home, I noticed a man standing at a street corner. I swung my cloak over my left shoulder, drew my rapier and went towards him. As I approached, he dashed at me, thrusting and calling out: “Cuckold! Rascall’ I knew his voice and ran my point into him and he fell dead. I then went to my friend’s house, held my tongue and got into bed.

‘Early next morning the Corregidor Don Pedro de Meneses came, roused me and walked me off. I reached the jail and was put in irons. About an hour after the Corregidor came with a notary and took my statement. I denied all knowledge of the business. Then they tortured me but I denied everything. When the case came on, witnesses I had never seen were produced and sentence of death was passed on me. I appealed, but an order to execute was issued. A monk came to hear my confession. I refused, and a cataract of monks was let loose on me.

‘I was rigged out in a taffeta suit and hoisted on to a horse. They took me down unfrequented streets until we came to the gibbet. They placed the rope round my neck-but at this moment a messenger galloped in from La Plata. He was sent by the Secretary under orders from the President Don Diego de Portugal and had an order to suspend my execution and transfer me to the High Court, twelve leagues away. The reason for this was extraordinary and a manifest mercy of God.

‘I was sent under escort to La Plata and in twenty four days was released.’

After this narrow escape Catalina set out again for Lima, where the Dutch were attacking the city with eight men-of-war. There she joined one of the five ships sent out from Callao to fight them.

‘In the engagement,’ she says, ‘they hammered our flagship so heavily that she sank and not more than three contrived to escape by swimming. The three were myself, a barefooted Franciscan monk, and a soldier. All the rest perished.’

At Cuzco, later, Catalina again became embroiled in a fight in a gambling den and in the fray killed a notorious man called ‘the Cid.’ She was severely wounded, being stabbed in the left shoulder and deeply cut in the thigh.

She was carried to her house and put to bed. A monk was called and she made her confession as she was afraid she was going to die. After she had received the Holy Viaticum she began to get better and gradually recovered, after being ill for four months.

A friend now came to her assistance and gave her a thousand pesos, three negroes and a mule, and thus accompanied she took the road to Guarnanga (today Huamanga, Peru). When she came to the bridge of Apurimac she was stopped by a constable who said: “You are arrested.” Eight other constables came up and endeavored to seize her, but Catalina resisted, drew her rapier and attacked them with vigour. During the fierce contest one of her negroes was killed and the constables, having lost three of their number, retreated, and Catalina proceeded on her way without further molestation.

On arriving at Guarnanga she put up at an inn where she stayed for a time. Soon she began to frequent the gambling houses again, and one day when she was playing the Corregidor came into the room. He looked hard at Catalina and asked her where she had come from. She replied: “From Cuzco.” He paused for a moment, then laid his hand on her, saying: “I arrest you.” Catalina jumped up and her rapier flashed out as she got between him and the door. He called for help, but there was such a rush to the door that she could not get out, so she drew her pistol. A way was made for her and she ran off as fast as she could.

She lay low for a few days and then thought it would be better to change her lodging. She left the inn at nightfall, but had not gone far when she was challenged by two men. They tried to seize her, but she drew her rapier and on hearing the men call out: “Help in the name of the law! ” a crowd gathered and there was a great uproar.

The Corregidor came out of the Bishop’s house with several constables and called on his men to seize her. Catalina drew her pistol, fired and shot one of them, but at that point the Bishop, accompanied by four torch-bearers, came out and pushed their way into the middle of the crowd.

As he reached Catalina he called out: “Ensign, give me your arms. ”

“I am surrounded by enemies, my Lord,” she replied.

“Give them up,” he cried. “You are out of harm’s way with me and I pledge my word to see you safe out of this whatever it costs me.”

“Most Illustrious Lord,” Catalina answered, “when we reach the cathedral I will kiss your Lordship’s feet.”

‘At this,’ she continued, ‘four of the Corregidor’s slaves took hold of me and I had to use my hands to floor one of them. The Bishop caught me by the arms, took my weapons from me and led me along to his house. He had my wound attended to, gave me supper and a bed, then gave orders for me to be locked in.

‘Next morning about ten o’clock, his lordship had me brought into his presence and asked me who I was, where I came from, and all about my life. Seeing the saintly man he was and feeling that I was in the presence of God, I said to him: “My Lord, the truth is I am a woman,’ Then I gave him an account of my life.

‘While my story lasted, the Bishop sat in amazement, and when I had finished shed scalding tears. He then sent me to rest. Next morning he was convinced on the evidence of two matrons that I was a maid entire. His lordship embraced me tenderly, and later placed me in the convent of St. Clare at Guamanga.’

On the death of the Bishop, Catalina left the town for Lima. She was carried in a litter accompanied by six priests, four nuns, and six armed men. When they arrived she was taken to the Palace to see the Viceroy and later continued her journey to Santa Fe de Bogota. Everywhere the people thronged to catch a glimpse of the now famous ‘Nun Ensign’ whose story had been spread abroad.

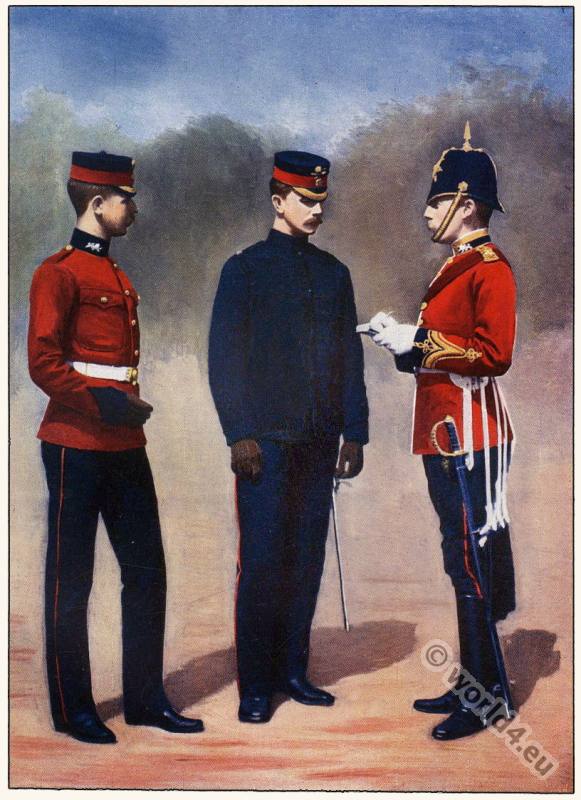

She embarked for Spain and arrived at Cadiz on 1 November 1624. When she landed she was still wearing her military uniform, and aroused great interest wherever she went. Having been granted a pension by the King she set off on a pilgrimage to Rome.

Her journey was an eventful one and she was arrested at one place and accused of being a Spanish spy. She was robbed of her money, her clothes were taken away, and she was put into irons for a fortnight. When she was liberated she resumed her journey and reached Rome on 6 June 1626.

She is described at that time as being ‘tall and burly for a woman, artificially flat-chested, not plain in feature and yet not beautiful, showing signs of hardship rather than of age. Her black hair was cut like a man’s and hung in a mane as was customary at the time.

She dressed in Spanish fashion, wore a sword tightly belted, her head inclined forward and her shoulders slightly stooped, more like a fiery soldier than a courtier. She gesticulated with her plump, fleshy but massive and powerful hands, in a manner vaguely suggestive of her sex.’

She was lionized in Rome and Pope Urban VIII granted her special permission to continue to wear men’s clothes and thus attired her portrait was painted by Francesco Crescentis.

After staying about six weeks in Rome she went to Naples in July 1626. ‘One day when sauntering on the quay,’ she says, ‘my attention was drawn to the guffaws of two wenches who were gossiping with a couple of youngsters and staring at me. I looked at them and one of them said: “Whither away my Lady Catalina?” I replied: “To give you a hundred thumps on the scruff of your necks my lady strumpets, and a hundred slashes to anyone who defends you!” They were silent and slunk off.’

At length, tiring of the monotony of city life, Catalina resolved to go abroad again, and she sailed for America in 1630. After her arrival she commenced business as a carrier and owned a number of negroes and mules

Nicolas de Renteria, who saw her at Vera Cruz in 1645, says: ‘She was regarded as a person of great courage and skilled in the use of arms. She dressed as a man and wore a rapier and dagger with silver mountings. She then looked about fifty years of age and was of good stature and stoutish build, with a dark complexion and a few hairs representing a moustache.

While returning to Vera Cruz after a journey, she was taken ill at Cuitlaxtla, where she died in 1650. All the notables of the district came to her funeral, and she was buried with great pomp by the Church, for the story of Catalina de Erauso who had fought so bravely for her country had not been forgotten.

Erauso’s sexual orientation is unclear. Her autobiography never evokes a physical desire for a man. On the other hand, she recounts at least one affair with a woman: at the end of chapter 5, the autobiography evokes how, in Lima, Peru, an innkeeper caught Erauso fooling around with one of the girls by “playing between her legs” while the young woman asked her to go get money for them to get married.

Later, Erauso quarrelled with her brother Miguel about a woman. Happy to have met another Basque so far from the country, Miguel, to whom Erauso did not reveal her sexual assignment, introduced her to his mistress. But Erauso comes back to see her in secret and Miguel finds out: the affair ends with a fight.

She is also approached on several occasions by mothers who saw her as a good match for their daughters, situations that she seems to have used mainly to obtain gifts and dowries rather than with the intention of actually marrying a woman.

Source: The mysteries of sex: women who posed as men and men who impersonated women by C. J. S. Thompson. London: Hutchinson, 1900.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.