Corsets and Crinolines 1st Edition by Norah Waugh & Judith Dolan.

In this classic book, Norah Waugh explores the changing shapes of women’s dress from the 1500s to the 1920s. Simple laced bodices became corsets of cane, whalebone and steel, while padding at shoulders and hips gave way to the structures of farthingales, hoops and bustles.

Stays and Corsets: Historical Patterns Translated for the Modern Body by Mandy Barrington.

Using her original pattern-drafting system, author Mandy Barrington will show you how to draft a historical pattern for a modern body shape, while still retaining an accurate historical silhouette.

CHAPTER IV.

Content: The bonnet à canon and sugarloaf headdress – Headdress of the women of Normandy at the present day – Odd dress of King Louis XI. – Return of Charles VIII. from Naples – A golden time for tailors and milliners – General change of fashion – Costumes of the time of Francis I. of France and Maximilian of Germany – General use of pins in France and England – Masks worn in France – Establishment of the empire of Fashion in France – The puffed or bouffant sleeves of the reign of Henry II. – The Bernaise dress – Costume of the unfortunate Marie Stuart – Rich dresses and long slender waists of the period – The tight-lacing of Henry III. of France – The Emperor Joseph of Austria, his edict forbidding the use of stays, and how the ladies regarded it – Queen Catherine de Medici and Queen Elizabeth of England – The severe form of Corsets worn in both France and England – The corps – Steel Corset covers of the period – Royal standard of fashionable slenderness – The lawn ruffs of Queen Bess – The art of starching – Voluminous nether-garments worn by the gentlemen of the period – Fashions of the ladies of Venice – Philip Stubs on the ruff – Queen Elizabeth’s collection of false hair – Stubs furious at the fashions of ladies – King James and his fondness for dress and fashion – Restrictions and sumptuary laws regarding dress – Side-arms of the period.

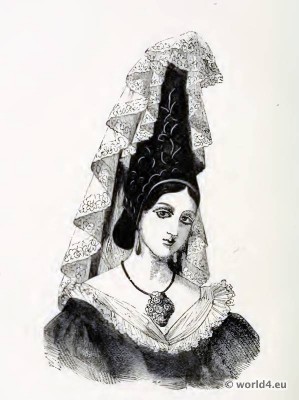

The bonnet à canon and sugarloaf headdress

From about 1380 to some time afterwards headdresses of most singular form of construction were in general wear in fashionable circles. One of these, the bonnet à canon, was introduced by Isabel of Bavaria. The “sugar-loaf“ headdress was also in high esteem, and considered especially becoming and attractive. The accompanying illustration faithfully represents both of these. The latter in a modified form is still worn by the women of Normandy. Throughout the reign of Louis XI. dress continued to be most sumptuous in its character.

Velvet was profusely worn, with costly precious stones encircling the trimmings. Sumptuary laws were issued right and left, with a view to the correction of so much extravagance, whilst the king himself wore a battered, shabby old felt cap, with a bordering of leaden figures of the Virgin Mary round it. The rest of his attire was plain and simple to a degree.

Return of Charles VIII. from Naples

Next we see his successor, Charles VIII., returning as a conqueror from Naples, dressed in the first style of Italian fashion. Then came a period of intense activity on the part of milliners and tailors, and a short time sufficed to completely metamorphose the reigning belles of the nation. Smaller, much more becoming and coquettish headdresses were introduced, and a general change of style brought about.

Germany participated in the same sudden change of fashion, which lasted until the reign of Francis I. Accompanying illustrations represent a lady of the court of Maximilian I. of Germany, and a lady of the court of Francis I. of France.

During his reign pins came into general use both in France and England, although their use had been known to the most ancient races, numerous specimens having been discovered in the excavations of Thebes and other Old World cities. Ladies’ masks or visors were also introduced in France at this period, but they did not become general in England until the reign of Queen Elizabeth. It was about this time that France commenced the establishment of her own fashions and invented for herself, and that the ladies of that nation became celebrated for the taste and elegance of their raiment.

Costume of the unfortunate Marie Stuart

On Henry II. succeeding Charles this taste was steadily on the increase. The bouffant, or puffed form of sleeve, was introduced, and a very pretty and becoming style of headdress known as the Bernaise.

The illustration shows a lady wearing this, the feather being a mark of distinction. The dress is made of rich brocade, and the waist exceedingly long (period, 1547.) The right-hand figure represents the unfortunate Marie Stuart arrayed in a court dress of the period, 1559.

On the head is a gold coronet; her under dress is gold brocade, with gold arabesque work over it; the over-dress is velvet, trimmed with ermine; the girdle consisted of costly strings of pearls; the sleeves are of gold-coloured silk, and the puffings are separated from each other by an arrangement of precious stones; the front of the dress is also profusely ornamented in the same manner; the frill or ruff was made from costly lace from Venice or Genoa, and was invented by this very charming but unfortunate lady; the form of the waist is, as will be seen on reference to this illustration, long, and shows by its contour the full influence of the tightly-laced corset beneath the dress, which fits the figure with extraordinary accuracy.

At this time Fashion held such despotic sway throughout the continent of Europe, that the Emperor Joseph of Austria, following out his extraordinary penchant for the passing of edicts, and becoming alarmed at the formidable lures laid out for the capture of mankind by the fair sex, passed a law rigorously forbidding the use of the corset in all nunneries and places where young females were educated; and no less a threat than that of excommunication, and the loss of all the indulgences the Church was capable of affording, hung over the heads of all those evil-disposed damsels who persisted in a treasonable manner in the practice of confining their waists with such evil instruments as stays.

Royal command, like an electric shock, startled the College of Physicians into activity and zeal, and learned dissertations on the crying sin of tight lacing were scattered broadcast amongst the ranks of the benighted and tight-laced ladies of the time, much as the advertisements of cheap furnishing ironmongers are hurled into the West-End omnibuses of our own day.

It is proverbial that gratuitous advice is rarely followed by the recipient. Open defiance was in a very short time bid to the edicts of the emperor and the erudite dissertations of the doctors. The corsets were, if possible, laced tighter than ever, and without anything very particular happening to the world at large in consequence.

Queen Catherine de Medici and Queen Elizabeth of England

On Queen Catherine de Medici, who, it will be seen, was a contemporary of Queen Elizabeth of England, assuming the position of power which she so long maintained at the court of France, costume and fashion became her study, and at no period of the world’s history were its laws more tremendously exacting, and the ladies of her court, as well as those in distinguished circles, were compelled to obey them. With her a thick waist was an abomination, and extraordinary tenuity was insisted on, thirteen inches waist measure being the standard of fashionable elegance, and in order that this extreme slenderness might be arrived at she herself invented or introduced an extremely severe and powerful form of the corset, known as the corps. It is thus described by a talented French writer:

“This formidable corset was hardened and stiffened in every imaginable way; it descended in a long hard point, and rose stiff and tight to the throat, making the wearers look as if they were imprisoned in a closely-fitting fortress.”

Steel Corset covers of the period

And in this rigid contrivance the form of the fair wearer was incased, when a system of gradual and determined constriction was followed out until the waist arrived at the required degree of slenderness, as shown in the annexed illustration. Several writers have mentioned the “steel corsets” of this period, and assumed that they were used for the purpose of forcibly reducing the size of the waist. In this opinion they were incorrect, as the steel framework in question was simply used to wear over the corset after the waist had been reduced by lacing to the required standard, in order that the dress over it might fit with inflexible and unerring exactness, and that not even a fold might be seen in the faultless stomacher then worn.

These corsets (or, more correctly, corsetcovers) were constructed of very thin steel plate, which was cut out and wrought into a species of open-work pattern, with a view to giving lightness to them. Numbers of holes were drilled through the flat surfaces between the hollows of the pattern, through which the needle and thread were passed in covering them accurately with velvet, silk, or other rich materials. During the reign of Queen Catherine de Medici, to whom is attributed the invention of these contrivances, they became great favourites, and were much worn, not only at her court, but throughout the greater part of the continent.

They were made in two pieces, opened longitudinally by hinges, and were secured when closed by a sort of hasp and pin, much like an ordinary box fastening. At both the front and back of the corsage a long rod or bar of steel projected in a curved direction downwards, and on these bars mainly depended the adjustment of the long peaked body of the dress, and the set of the skirt behind.

The votaries of fashion of Queen Elizabeth’s court were not slow in imitating in a rough manner the new continental invention, and the illustrations taken from photographs, will show that, although not precisely alike, the steel corset-covers of England were much in principle like those of France, and the accompanying illustration represents a court lady in one of them. We have no evidence, however, that their use ever became very general in this country, and we find a most powerful and unyielding form of the corset constructed of very stout materials and closely ribbed with whalebone superseding them.

This was the corps before mentioned, and its use was by no means confined to the ladies of the time for we find the gentlemen laced in garments of this kind to no ordinary degree of tightness. That this custom prevailed for some very considerable time will be shown by the accompanying illustration, which represents Queen Catherine’s son, Henry III. (who was much addicted to the practice of tight lacing), and the Princess Margaret of Lorraine, who was just the style of figure to please his taste, which was ladylike in the extreme.

Eardrops in his ears, delicate kid gloves on his hands; hair dyed to the fashionable tint, brushed back under a coquettish little velvet cap, in which waved a white ostrich’s feather; hips bolstered and padded out, waist laced in the very tightest and most unyielding of corsets, and feet incased in embroidered satin shoes.

Henry was a true son of his fashionable mother, only lacking her strong will and powerful understanding. England under Elizabeth’s reign followed close on the heels of France in the prevailing style of dress. From about the middle of her reign the upper classes of both sexes carried out the custom of tight lacing to an extreme which knew scarcely any bounds. The corsets were so thickly quilted with whalebone, so long and rigid when laced to the figure, that the long pointed stomachers then worn fitted faultlessly well, without a wrinkle, just as did the dresses of the French court over the steel framework before described.

The following lines by an old author will give some idea of their unbending character:

“These privie coats, by art made strong,

With bones, with paste, with such-like ware,

Whereby their back and sides grow long,

And now they harnest gallants are;

Were they for use against the foe

Our dames for Amazons might go.”

On examining the accompanying illustration representing a lady of the court of Queen Elizabeth, it will be observed that the farthingale or, verdingale, as it is sometimes written, and from which the modern crinoline petticoat is borrowed, serves to give the hips extraordinary width, which, coupled with the frill round the bottom of the stomacher, gave the waist the appearance of remarkable slenderness as well as length. The great size of the frills or ruffs also lent their aid in producing the same effect.

It was in the reign of Elizabeth that the wearing of lawn and cambric commenced in this country; previously even royal personages had been contented with fine holland as a material for their ruffs. When Queen Bess had her first lawn ruffs there was no one in England who could starch them, and she procured some Dutch women to perform the operation.

It is said that her first starcher was the wife of her coachman, Guillan. Some years later, afterward, in 1564 one Mistress Dinghen Vauden Plasse, born at Teenen in Flanders, the wife of a Flemish knight, established herself in London as a professed starcher. She also gave lessons in the art, and many ladies sent their daughters and kinswomen to learn of her. Her terms were five pounds for the starching and twenty shillings additional for learning to “seeth” the starch. Saffron was used with it to impart to it a yellow colour which was much admired.

The gentlemen of the period indulged in nether garments so puffed out and voluminous that the legislature was compelled to take the matter in hand. We read of “a man who, having been brought before the judges for infringing the law made against these extensive articles of clothing, pleaded the convenience of his pockets as an excuse for his misdemeanour.

They appeared, indeed, to have answered to him the purposes both of wardrobe and linen cupboard, for from their ample recesses he drew forth the following articles viz., a pair of sheets, two tablecloths, ten napkins, four shirts, a brush, a glass, a comb, besides nightcaps and other useful things; his defence being – ‘Your worship may understand that because I have no safer storehouse these pockets do serve me for a roome to lay up my goodes in; and though it be a strait prison, yet it is big enough for them.'” His discharge was granted, and his clever defence well laughed at.

Fashions of the ladies of Venice

The Venetian ladies appear to have been fully aware of the reducing effect of frills and ruffs on the apparent size of waist of the wearer, and they were, as the annexed illustration will show, worn of extraordinary dimensions; but the front of the figure was, of course, only displayed, and on this all the decoration and ornamentation that extravagant taste could lavish was bestowed.

The Elizabethan ruff, large as it was, bore no comparison with this, and was worn as shown in the accompanying portrait of the “Virgin Queen,” who indulged in numerous artifices for heightening her personal attractions.

The ruffs and frills of the period so excited the ire of Philip Stubs, a citizen of London, that in his work, dated 1585, he thus launches out against them in the quaint language of the time:

“The women there use great ruffes and neckerchers of holland, laune, cameruke, and such clothe as the greatest threed shall not be so big as the least haire that is, and lest they should fall downe the are smeared and starched in the devil’s liquor, I mean starche; after that dried with great diligence, streaked, patted, and rubbed very nicely, and so applied to their goodly necks, and withal underpropped with supportasses (as I told you before), the stately arches of pride; beyond all this they have a further fetche, nothing inferiour to the rest, as namely-three or four degrees of minor ruffes placed gradation, one beneath another, and al under the mayster deuilruffe.

The skirtes then, of these great ruffes are long and wide, every way pleated and crested full curiously, God wot! Then, last of all, they are either clogged with gold, silver, or silk lace of stately price, wrought all over with needleworke, speckeled and sparkeled here and there with the sunne, the mone, the starres, and many other antiques strange to beholde.

Some are wrought with open worke downe to the midst of the ruffe, and further, some with close worke, some wyth purled lace so cloied, and other gewgaws so pestered, as the ruffe is the least parte of itselfe. Sometimes they are pinned upp to their eares, sometimes they are suffered to hange over theyr shoulders, like windemill sailes fluttering in the winde; and thus every one pleaseth her selfe in her foolish devises.”

In the matter of false hair her majesty Queen Elizabeth was a perfect connoisseur, having, so it is said, eighty changes of various kinds always on hand. The fashionable ladies, too, turned their attention to artificial adornment of that kind with no ordinary energy, and poor old Stubs appears almost beside himself with indignation on the subject, and thus writes about it:

“The hair must of force be curled, frisled, and crisped, laid out in wreaths and borders from one ear to another. And, lest it should fall down, it is underpropped with forks, wires, and I cannot tell what, rather like grim, stern monsters than chaste Christian matrons. At their hair thus wreathed and crested are hanged bugles, ouches, rings, gold and silver glasses, and such like childish gewgaws.”

The fashion of painting the face also calls down his furious condemnation, and the dresses come in for a fair share of his vituperation, and their length is evidently a source of excessive exasperation. We give his opinions in his own odd, scolding words:

“Their gownes be no less famous than the rest, for some are of silke, some velvet, some of grograine, some of taffatie, some of scarlet, and some of fine cloth of x., xx., or xl. shillings a yarde. But if the whole gowne be not silke or velvet, then the same shall be layd with lace two or three fingers broade all over the gowne, or els the most parte, or if not so (as lace is not fine enough sometimes), then it must bee garded with great gardes of velvet, every yard fower or sixe fingers broad at the least, and edged with costly lace, and as these gownes be of divers and sundry colours, so are they of divers fashions chaunging with the moone-for some be of new fashion, some of the olde, some of thys fashion, and some of that; some with sleeves hanging downe to their skirtes, trailing on the ground, and cast over their shoulders like cows’ tailes; some have sleeves muche shorter, cut vp the arme and poincted with silke ribbons, very gallantly tied with true love’s knottes (for so they call them); some have capes reachyng downe to the midest of their backes, faced with velvet, or els with some wrought silke taffatie at the least, and fringed about very bravely (and to shut vp all in a worde), some are peerled and rinsled downe the backe wonderfully, with more (89) knackes than I can declare.

Then have they petticoates of the beste clothe that can be bought, and of the fayrest dye that can be made. And sometimes they are not of clothe neither, for that is thought too base, but of scarlet grograine, taffatie, silke, and such like, fringed about the skirtes with silke fringe of chaungeable colour, but whiche is more vayne, of whatsoever their petticoates be yet must they have kirtles (for so they call them), either of silke, velvett, grogaraine, taffatie, satten, or scarlet, bordered with gardes, lace, fringe, and I cannot tell what besides.”

Stubs furious at the fashions of ladies

History fails to enlighten us as to whether the irascible Stubs was blessed with a stylish wife and a large family of fashionable daughters, but we rather incline to the belief that he must have been a confirmed old bachelor, as we cannot find that he was ever placed in a lunatic asylum, a fate which would inevitably have befallen him if the fashions of the time had been brought within the sphere of his own dwelling.

It is somewhat singular that, writing, as he did, in the most violent manner against almost every article of personal adornment, and every artifice of fashionable life, the then universal and extreme use of the corset should have escaped censure at his hands.

King James and his fondness for dress and fashion

King James, who succeeded Elizabeth, manifested an inordinate fondness for dress. We read that:

“Not only his courtiers, but all the youthful portion of his subjects, were infected in a like manner, and the attire of a fashionable gentleman in those days could scarcely have been exceeded in fantastic device and profuse decoration. The hair was long and flowing, falling upon the shoulders; the hat, made of silk, velvet, or beaver (the latter being most esteemed), was high-crowned, narrow-brimmed, and steeple-shaped. It was occasionally covered with gold and silver embroidery, a lofty plume of feathers, and a hatband sparkling with gems being frequently worn with it. It was customary to dye the beard of various colours, according to the fancy of the wearer, and its shape also differed with his profession.

The most effeminate fashion at this time was that of wearing jeweled rings in the ears, which was common among the upper and middle ranks. Gems were also suspended to ribbons round the neck, while the long ‘lovelock’ of hair so carefully cherished under the left ear was adorned with roses of ribbons, and even real flowers.

The ruff had already been reduced by order of Queen Elizabeth, who enacted that when reaching beyond ‘ a nayle of a yeard in depth’ it should be clipped. In the early past of her reign the doublet and hose had attained a preposterous size, especially the nether garments, which were stuffed and bolstered with wool and hair to such an extent that Strutt* tells us, on the authority of one of the Harleian manuscripts, that a scaffold was erected round the interior of the Parliament House for the accommodation of such members as wore them! This was taken down in the eighth year of Elizabeth’s reign, when this ridiculous fashion was laid aside.

The doublet was afterwards reduced in size, but still so hard-quilted that the wearer could not stoop to the ground, and was incased as in a coat of mail. In shape it was like a waistcoat, with a large cape, and either close or very wide sleeves. These latter were termed Danish. A cloak of the richest materials, embroidered in gold or silver, and faced with fox skin, lambskin, or sable, was buttoned over the left shoulder. None, however, under the rank of an earl were permitted to indulge in sable facings.

The hose were either of woven silk, velvet, or damask; the garters were worn externally below the knee, made of gold, silver, or velvet, and trimmed with a deep gold fringe. Red silk stockings, parti-colored gaiters, and even ‘cross gartering’ to represent the Scotch tartan, were frequently seen. The shoes of this period were cork-soled, and elevated their wearers at least two or three inches from the ground. They were composed of velvet of various colours, worked in the precious metals, and if fastened with strings, immense roses of ribbon were attached to them, variously ornamented, and frequently of great value, as may be seen in Howe’s continuation of Stowe’s Chronicle, where he tells us ‘men of rank wear garters and shoe-roses of more than five pounds price.’ The dress of a gentleman was not considered perfect without a dagger and rapier.

The former was worn at the back, and was highly ornamented. The latter having superseded, about the middle of Elizabeth’s reign, the heavy two-handed sword, previously used in England, was, indeed, chiefly worn as an ornament, the hilt and scabbard being always profusely decorated.”

- Joseph Strutt (1749 – 1802) was an English engraver, artist, antiquary and writer.

Source: The Corset and the Crinoline. A Book of Modes and Costumes from remote Periods to the Present Time by W. B. L. (William Berry Lord). With 54 Full-Page and other Engravings. London: Ward, Lock, and Tyler. Warwick House, Paternoster Row. 1868.

Related

Corsets and Crinolines 1st Edition by Norah Waugh & Judith Dolan.

In this classic book, Norah Waugh explores the changing shapes of women’s dress from the 1500s to the 1920s. Simple laced bodices became corsets of cane, whalebone and steel, while padding at shoulders and hips gave way to the structures of farthingales, hoops and bustles.

Stays and Corsets: Historical Patterns Translated for the Modern Body by Mandy Barrington.

Using her original pattern-drafting system, author Mandy Barrington will show you how to draft a historical pattern for a modern body shape, while still retaining an accurate historical silhouette.