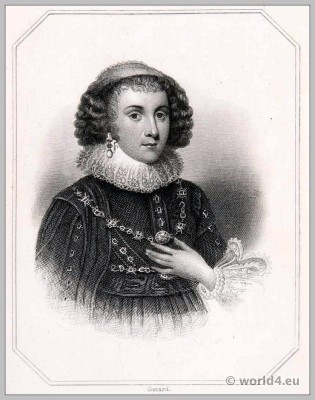

Mary Herbert, countess of Pembroke, née Mary Sidney.

Mary Herbert, Countess of Pembroke (1561-1621) was a scholar noble English writer in Elizabethan time and the center of an artist circle. She enjoyed a humanist education: French, Italian (by an Italian woman), Greek and Latin, as well as music lessons, playing lute, virginal, possibly violin and sang. Her brothers were the poet Sir Philip Sidney, Henry Sidney, Earl of Leicester and Sir Robert Sidney.

The parents were Sir Henry Sidney (1529-1586), the Lord Deputy of Ireland and Mary Sidney, daughter of John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland and under Edward VI. High Protector of England. In her country estate, she gained over 20 years in a circle of poets and musicians around (“Wilton Circle”), including Edmund Spenser (he dedicated his “Ruines of Time”), Michael Drayton, Sir John Davies, who was also her secretary , and Samuel Daniel.

Like her brother, she tried in her circle to promote the English language and refine, in particular by translations of the Bible. She herself was well versed and active in the Calvinist theology in the help for Huguenot refugees. 1577 she married the much older Henry Herbert, 2nd Earl of Pembroke (1534-1601), lived with on the family seat of Pembroke at Wilton House in Salisbury (Wiltshire) and in London in Baynard’s Castle.

She also had an alchemy lab at Wilton House. Adrian Gilbert, Walter Raleigh’s half-brother, assisted her in her experiments (which still contain secret ink recipes, for example) and designed her garden according to strictly geometric rules inspired by occult thought.

She died in her London house in Aldersgate Street of chickenpox and is buried next to her husband in the Cathedral of Salisbury, buried under the stairs to the choir.

MARY SIDNEY, COUNTESS OF PEMBROKE. WILTON HOUSE PICTURES.

By Marc Geerarts (Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger c. 1561/62 – 19 January 1636). 36 in. H. 15½ in. W. Panel. Library (at Wilton House).

Three-quarter length, standing on the left of a crimson velvet chair, and holding a devotional book, bound in red, in her right hand. Black figured velvet dress, white lace cuffs and coif, deep muslin ruff edged with lace: in the background a dark green curtain.

Although there is no documentary evidence to prove that this picture was the work of Geerarts, it agrees very closely to many of the pictures which are ascribed to him. At the same time it must be admitted that the portrait of Mary Sidney in the National Portrait Gallery, which is said to be the work of Geerarts himself, differs in many important points from the Wilton Panel. Until therefore the authenticity of one of these pictures is established beyond doubt, both must continue to be provisionally ascribed to the same hand.

Exhibited at the Exhibition of Art Treasures, 1857, and the Tudor Exhibition, Manchester, 1897.

Mary Sidney, 1) Countess of Pembroke, was born about the middle of the sixteenth century, and was the daughter of Sir Henry Sidney, Knight of the Garter, Lord Deputy of Ireland, and Lord President of Wales, by the Lady Mary, eldest daughter of John, Duke of Northumberland, and sister to the matchless Sir Philip Sidney. She was married about the year 1576 to Henry, 2) Earl of Pembroke, by whom she had issue, William, 3) who succeeded him in his honours, and Philip, 4) and a daughter Anne, who died young. Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, her uncle, made the match for her, and paid part of her fortune, which Sir Henry acknowledges as a favor to him by his letter from Dundalk in Ireland, bearing date the 4th of Feburary, 1576. 5)

The date of Mary Sidney’s birth is now known to have been 27th October, 1561, and her birthplace Ticknell, 6) Bewdly, in Worcestershire. Her godfather was William, first Earl of Pembroke, father of her future husband. At fifteen Queen Elizabeth commanded her presence at Court, and she was married three years later.

While residing at Wilton she was joined, in 1580, by her brother, Sir Philip, banished from Court owing to a quarrel with the Earl of Oxford. 7) It was during this enforced retirement that he composed his famous Pastoral Romance, “done in loose sheets of paper, most of it in my sister’s presence, the rest by sheets sent to her as fast as they were wrote,” which was first published in 1590 8) under the title of the Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia. 9) There is an avenue at Wilton still known by his name, under the shadow of which, according to local tradition, he walked while composing this work.

- 1) George Ballard, from whose Memoirs of Several Ladies of Great Britain, Oxford, 1752, this account is taken, spells her name Sydney. In a letter dated “Frome Wilton this 16th of December, 1572,” her brother signs himself “Philippe Sidney.”

2) She was the third wife of Henry, second Earl of Pembroke, who married, firstly, Catherine Grey, daughter of Henry, Earl of Suffolk, and secondly, Catherine Talbot, daughter of Gilbert, Earl of Shrewsbury. There being no portrait of this nobleman at Wilton, a short notice of his life is given in Appendix III. - 3) See Van Dyck.

- 4) Ibid.

- 5) Collins, Sydney Papers, vol. i, p. 88. Sir Henry Sidney to Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, Dundalk, 4th February, 1576. “Your Lordshyppys later wrytten Letter I received, the same Day I dyd the first, together with one from my Lord of Penbrooke to your Lordshyp; by both whych I find, to my excedyng great Confort, the Lykleod of a Maryage betwyne his Lordshyp and my Doghter, whych great Honor to me, my mean Lynuage and Kyn, I attribute to my Match in your noble House; for whych I acknoleg myself bound to honour and sarve the same, to the uttermost of my Pouer, yea so joyfully have I at Hart, that my dere Chyldys so happy an advancement as thys ys, as, in Troth, I would ly a Year in close Pryson, rather than yt should breake. But, alas, my derest Lord, myne Abylyte answereth not my harty Desyer. I am poore; myne Estate, as well in Lyvelod and Moveable, is not unknown to your Lordshyp, whych wantyth mutch to make me able to equall that, whych I know my Lord of Penbrook may have. Twoo Thousand l. I confess I have bequethed her, which your Lordshyp knowyth I might better spare her when I wear dead, than one Thousand lyving; and, in troth, my Lord, I have yt not, and borro yt I must, and so I wyll: and if your Lordshypp wyll get me Leave, that I may feed my Eyes wyth that joyfull Syght of thear Couplyng, I wyll gyve her a Cup worth fyve Hundreth 1. Good, my Lord, bear wyth my Poverty, for if I had it, lyttel would I regard any Sum of Money, but Wyllyngly would give it, protesting before the Almighty God, that if He, and all the Powers on Earth, would give me my Choyse for a Husband for her, I would choose the Earl of Penbrooke. I wryte to my Lord of Penbrooke, whych hearwyth I send your Lordshyp; and thus I end, in answering your most welcome and honourable Letter wyth my harty Prayer to Almighty God to perfect your Lord- shyppes good Work, and requyte you for the same; for I am not able.”

- 6) Philip Sidney, The Sidneys of Penshurst, p. 111. It was formerly called Tickenhill Palace, and was the Council-House of the Lords President of the Marches of Wales.

- 7) At Whitehall, one September morning, 1579, whilst playing tennis, Philip was insulted by Lord Oxford, a man of unprincipled character, in whom pride of race amounted almost to a disease. In Philip he met a formidable antagonist, who quickly gave him the lie, and challenged him to a duel. This the Earl declined, and endeavored to assassinate his opponent instead. On the broil becoming known to the Queen, she directed Philip to apologize, but he refused. A few months later the royal anger was again excited by a letter from Philip entreating, almost commanding, Elizabeth not to marry the Catholic Duke of Anjou. After shedding tears, probably more in anger than sorrow, the Queen banished Philip from Court.—The Sidneys of Penshurst, p. 68.

- 8) Sir Philip Sidney was killed in 1586 at the battle of Zutphen. In his Will, proved the 19th of June, 1589, are the following bequests: “Item I give and bequeathe to my dear Sister the Countess of Pembroke my best jewell beset with diamonds. Item I will that my Wife cause three rings to be made, and in every of them a Diamond to be presented and given, one to the Right Honourable the Earl of Huntingdon, one to the Right Honourable the Earl of Pembroke, and the third to my very good Lady the Countess of Sussex in token of my very dutiful love to everyone of them. “-Sydney Papers.

- 9) The wonderful popularity of the Arcadia may be gauged by the following list of the principal editions, for which I am indebted to Mr. Bain.

1st Edition – 4to – 1590

2nd do. – do. – 1593

3rd do. – Fol.- 1599

4th do. – do. – 1605

4th do. – do. – 1613

5th do. – do. – 1623

6th do. – Fol. – 1627

7th do. – do. – 1629

8th do. – do. – 1633

9th do. – do. – 1638

10th do. – do. – 1665

The editions of 1605 and 1613 are both called 4th edition on title. The title and dedication to the 1st edition run as follows: “The Covntesse of Pembroke’s Arcadia: written by Sir Philippe Sidnei: London Printed for William Ponsonbie: Anno Domini 1590. ‘To my Deare Ladie and Sister The Countesse of Pembroke.'”

Like her brother, Mary Sidney herself was devoted to literature, among her works being: A Discourse of Life and Death, written in French by Philip Morney, done into English by the Countess of Pembroke, dated the 13th of May, 1590, at Wilton. Printed at London for William Ponsonby, 1600. 12mo.

The Tragedie of Antonie. Done into English by the Countess of Pembroke. 12mo. London, 1595. This little book is not paged, but contains fifty-four leaves. Dated at Ramsbury 26th November, 1590.

She is also said to have translated many of the Psalms into English verse, “which are bound in velvet, and, as I am told, still preserved in the library at Wilton.” 1)

Respecting Lady Pembroke’s claim to a version of the Psalms ascribed to her, there has been some difference of opinion. By Sir J. Harrington, A. Wood, and Dr. Thomas she is supposed to have had the assistance of Bishop Babington (at one time her chaplain); by Amelia Lanter, in 1611, she is considered as sole translator; but it is probable that Dr. Donne affords the most authentic information when he speaks of the Sydnean Psalmes as a joint labour, in a long copy of encomiastic verses upon the translation of them by Sir Philip Sidney and the Countess of Pembroke, his sister (Donne’s Poems, 1635, p. 366). This information is corroborated in a Psalm inserted in the Guardian (No. 18, Psalm cxxxvii), from a manuscript, said to be Sir Philip Sidney’s, which nearly corresponds with a version of the same Psalm printed in Nugae Antiquae (vol. ii, p. 407, last edition), as by the Countess of Pembroke. 2)

1) I have been unable to find this volume in the library at Wilton.

2) The above is Park’s note to Walpole’s Royal and Noble Authors, ed. 1806, vol. ii, p. 191.

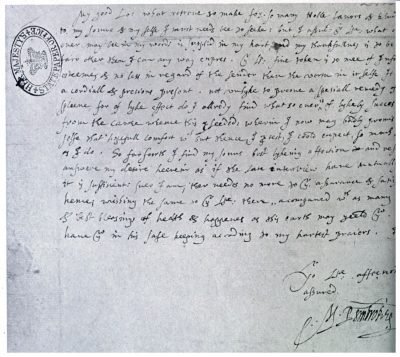

Letter above: To the Right honorable my very good Lo: the Lo: Threasorer these. 1)

My good Lo: what retorne to make for so many noble favors and kindness both to my sonne and my selfe I must needs bee to seeke, but I assuer your L-p what defect so euer may bee in my words is supplied in my hart, and my thankfulnes is to bee conceued far other then I can any way expres. Your Lps fine token is to mee of infinight esteeme and no less in regard of the sender then the vertu in it self. I t is indeed a cordi all and precious present, not unlyke to prooue a speciall remedy of the sadd spleene, for of lyke effect do I alredy find what so euer is of lykely succes proseeding from the cause whence this proseeded: wherin I now may boldly promis to my selfe that hopeful comfort which, but thence I protest I coold [not] expect so much to joy in as I do. So farr foorth I find my sonns best lykeing affection and resolution to answere my desire heerin, as, if the late interuiew haue mutually wrought, it is sufficient: suer I am ther needed no more to your assurance and satisfaction hence; wishing the same to your Lp there, accompanied with as many comforts and blessings of health and happiness as this earth may yeeld you. God haue you in his safe keeping according to my hartest praiers.I rest

.

Your Lps affectionatly assured

M. PEMBROKE. 2)

[Endorsed by Lord Burghley, 16 August, 1597. Delivered by the hand of Arthur Massinger.]

1 State Papers Dom., Eliz., vol. 264, ff. 84 and 85. (In Calendar vol. 33, p. 489·)

2 This letter was printed in full by J. P. Collier: Bibliographical and Critical Account of the Rarest Books in English Literature (London, 1865), vol. I, p. xxxi. Collier says: “The following letter from the Countess of Pembroke, referring to the proposed marriage of her son with Bridget, the daughter of Lord Burghley, has never been printed . . . To it is appended a letter from the Earl of Pembroke, who seems to have left thematter much to his wife and Massinger.” The young girl, however, must have been Lord Burghley’s granddaughter, the child of his second daughter, Anne, who married the Earl of Oxford. Nor does Lord Pembroke’s long letter of September 3, following, support Collier’s surmise that he was indifferent.

Of this translation of the Psalms her sons’ tutor, Samuel Daniel, in his Tragedie of Cleopatra, 1594, writes:

Those Hymnes which thou dost consecrate to Heaven,

Which Israel’s Singer to his God did frame:

Unto thy voyce Eternitie hath given,

And makes thee deare to him from whence they came,

In them must rest thy venerable name,

So long as Sion’s God remaineth honoured;

And till confusion hath all zeal bereaven,

And murdered Faith, and Temples ruined.

By this (Great Lady) thou must then be Knowne,

When Wilton lies low levell’d with the ground:

And this is that which thou maist call thine owne,

Which sacreligious Time cannot confound;

Here thou surviv’st thyself, heere thou art found

Of late succeeding ages, fresh in fame:

This monument cannot be overthrowne,

Where in eternal Brasse remaines thy Name.

“Lady Pembroke’s edition of the Psalms remained in manuscript till 1823, when it was printed from a fine copy, transcribed early in the seventeenth century by John Davies of Hereford, who died in the year 1618. Its eventual appearance in print was due to the enterprise of James Boswell the younger, second son of the biographer of Dr. Samuel Johnson, who intended to write an introduction to the volume, but died in 1822, just before he could put his praiseworthy plan into execution.” 1)

Other known works of Mary Sidney are:

An Elegy on Sir Philip Sidney, printed in Spenser’s Astrophel, 1595.

A Pastoral Dialogue in praise of Astraea, i.e., Queen Elizabeth, published in Davison’s Poetical Rhapsody in 1602.

The Countess of Pembroke’s Passion. A long poem in six-line stanzas in the Slonian MSS. (No. 1303). 2)

1) Philip Sidney, The SubJect 0./ all Verse, Oxford, 1907.

2) The above is Park’s note to Walpole’s Royal and Noble Authors, ed. 1806, vol. ii, p. 19I.

Besides the Arcadia, many other works were dedicated to the Countess, among them two by Abraham Fraunce, published in 1591, and entitled: The Countess of Pembroke’s Ivychurch: “Containing the affectionate Life and un fortunate Death of Phillis and Amyntas.” 1)

The Countess of Pembroke’s Emanuel: “Containing the Nativity, Burial, and Resurrection of Christ, together with certain Psalms of David.”

Lady Pembroke survived her husband twenty years, and died at her house in Aldersgate Street, 2) probably Crosby Hall, and was buried in the Cathedral Church of Salisbury. The lack of a monument 3) over her tomb is amply compensated for by William Browne’s 4) graceful epitaph:

Underneath this sable Herse

Lyes the Subject of all Verse;

Sydney’s Sister, Pembroke’s Mother;

Death, ere thou hast killed another

Faire, and learn’d, and good as she,

Tyme shall throwe a Dart at thee. 5)

To these lines her son William, third Earl of Pembroke, added six more much inferior in every way, and they are inserted here merely to relieve William Browne and Ben Jonson of the suspicion of their authorship:

Marble Pyles let no man rayse

To her Name, for after Daies

Some kinde Woman, borne as she,

Reading this, like Niobe,

Shall turne Marble, and become

Both her Mourner and her Tombe. 6)

1) Ballard, p. 260.

2) 25th September, 1621.

3) This deficiency has been supplied by a tablet recently placed in the Chancel by Sidney, fourteenth Earl of Pembroke, to mark the probable place of her interment .

4) William Browne was born at Tavistock, educated at Exeter College, Oxford. In 1624 he became tutor to Philip, Earl of Carnarvon (see VAN DYCK), who was killed at Newbury in 1643. He then went into the family of the Earl of Pembroke. While under this patron, according to Wood, he “Acquired Wealth and purchased an Estate.” He died in 1645.

5) There are many versions of these lines which differ slightly in the wording; I have taken this version (which I prefer) from Collins, Sydney Papers, ed. 1746, p. 97. With regard to the authorship of these lines, it is generally accepted that they are not by Ben Jonson, to whom they were formerly ascribed, but to William Browne, author of Britannia’s Pastorals. In Gifford’s Works of Ben Jonson, 1816, vol. viii, p. 337, is the following note: “The exquisite beauty of this little piece (the most perfect of its kind) has drawn a word of approbation from the stern and cynical Osborne. ‘Lest I should seem [he says] to trespass upon truth in the praise of this lady, I shall leave the world her epitaph, in which the author doth manifest himself a poet in all things but untruth.'”

6) If the name of Browne be substituted for that of Ben Jonson, the following note will be found of interest. “On this paltry addition the editors of the Secret History of the Court of James I, who manifest on all occasions a strange hostility to our author, observe: ‘It is possible that Jonson cancelled these lines on account of the outrageous wit with which they disgrace the commencement,’ vol. i, p. 225· It is also possible that Jonson never saw them. Setting aside the absurdity of supposing the poet to say in one line that such another character would never appear, and to admit in the next that nothing was so likely, the critics ought to have known (for the fact was very accessible) that the verses in question were copied from the poems of the Earl of Pembroke, a humble votary of the Muses, to whose pen they are assigned by the prefix of his usual initials.”-Gifford.

Since the above was written, Mr. Philip Sidney has published a small book entitled The Subject of all Verse, in which he deals at length with the question of the authorship of the famous epitaph, and concludes his investigations as follows:

“To sum up the vexed question of the authorship of the epitaph, it may be reasonably contended that, if it cannot be proved to a demonstration that William Browne wrote it, or the first sextain (sestina) of it at any rate, there still exists far more evidence to be quoted in his favor than in that of all the other claimants taken together. The shadowy legend of Ben Jonson’s authorship seems to rest mainly on Peter Whalley’s bald statement that the epitaph was ‘universally assigned to him.’ In this respect, Whalley may possibly have thought that the style of the first sextain of the epitaph sufficiently resembled that in Jonson’s lines:

Underneath this stone doth lie

As much beauty as could die;

Which in life did harbour give

To more virtue than doth live;

to render it likely that Ben must have written the first sextain. But as early as the year 1629 the epitaph had appeared in print, in the fourth edition of William Camden’s Remaines Concerning Brittaine without any reference being made to Ben Jonson as its author.

At what precise day, between, of course, the years 1621 and 1629, the epitaph was written, it is difficult to calculate, but it was very probably composed when William Browne was staying at Wilton, in which case William, Earl of Pembroke, might have been responsible for the latter part of it. But it should be remembered that Browne was also the author of a poem on Lady Pembroke entitled An Elegy on the Countess Dowager of Pembroke, consisting of one hundred and seventy-nine lines, of which I quote the first nine below, for they contain proof in the poet’s own words of his warm regard for Lady Pembroke, and of the fact that he knew her well:

Time hath a long course run since thou wert clay;

Yet had’st thou gone from us but yesterday,

We in no nearer distance should have stood,

Than if thy Fate had call’d thee ere the flood;

And I that knew thee, shall no less cause have

To sit me down and weep beside the grave

Many a year from hence, than in that hour

When all amazed, we had scarce the power

To say that thou wert dead.”

It is possible that this favourite black dress of Mary Sidney may have descended to her from her grandmother through her mother. In the former’s will is the following bequest: “To my daughter Mary Sidney my gown of black barred velvet furred with sables etc. and a gown with a high back of fair wrought velvet.”-From the Will of Lady Jane Guilford, Duchess of Northumberland, who died in 1555. Sydney Papers, vol. i, p. 34.

Source:

- Wilton house pictures; containing a full and complete catalogue and description … by Sidney Herbert Earl of Pembroke. London, Printed at the Chiswick press, 1907.

- Mary Sidney, Countess of Pembroke by Frances Campbell (Berkeley) Young. London D. Nutt, 1912.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.