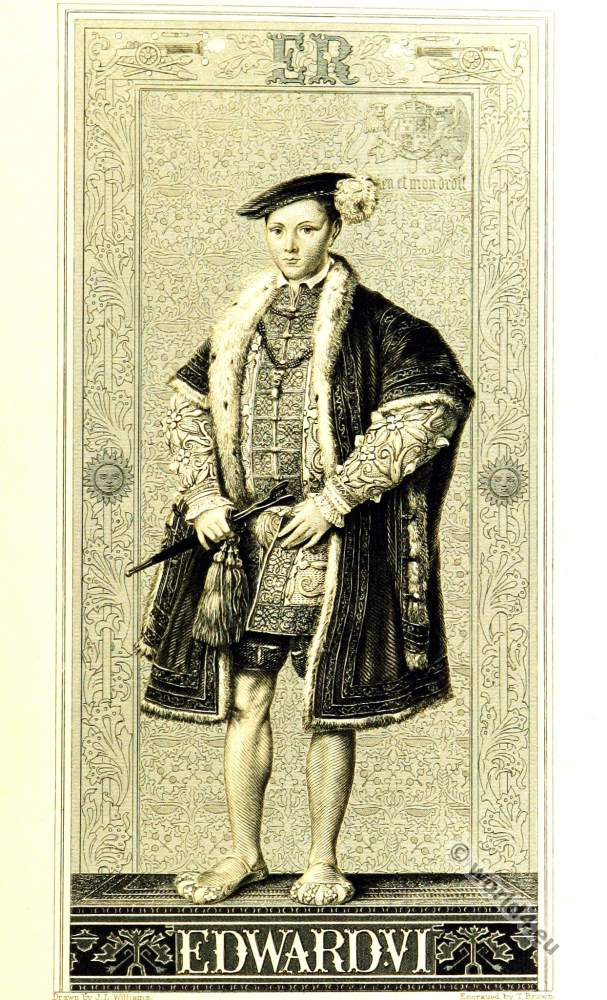

Edward VI (Edward Tudor; October 12, 1537 at Hampton Court Palace; † July 6, 1553 at Greenwich) was the third monarch of the Tudor dynasty and King of England and Ireland from 1547 to 1553. He was the only surviving legitimate son of Henry VIII (with his third wife Jane Seymour) and ascended the English throne after the latter’s death at the age of nine. Because he died at the age of 15, a council of regency existed throughout his reign, appointed first by his uncle Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset (1547-1549), and after his execution by John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland (1550-1553).

KING EDWARD THE SIXTH, HOLBEIN. 1553

From the Collection of the Right Honourable the Earl of Egremont, at Petworth.

KING EDWARD THE SIXTH.

THE son of Henry the Eighth by Jane Seymour, was born at Hampton Court on the 12th of October, 1537, and died at Greenwich on the sixth of July, 1553.

The annals of this Prince present little more to our view than the strange events which attended the struggle between Seymour and Dudley for the possession of his person and authority.

The bloody war with Scotland, and the dangerous insurrections which succeeded at home, occupied the ardent minds and employed the talent soft hose chiefs during the first two years of his reign; but the return of national peace gave birth to the bitterest discord between them; and their wisdom and bravery, which in the late public exigencies had shone resplendently in the council and in the field, presently sank into the contracted cunning and petty malice of factious politicians.

The Protector sought to intrench himself in the strong hold of popular favour, and was perhaps the first English nobleman who endeavoured to derive power or security from that source: his antagonist, too proud and too artful to engage in an untried scheme, humiliating in its progress and uncertain in its event, threw himself into the arms of a body of discontented Nobles, lamenting the fallen dignity of the Crown, and the tarnished honour of their order. He proved successful: the Protector was accused of High Treason, and suffered on the scaffold, and the young King was transferred to Dudley, together with the regal power.

These circumstances, well known as they are, will be found to throw a new lustre on Edward’s character. In this convulsed time, so adverse to every sort of improvement either in the morals or less important accomplishments of the youthful Prince; under the disadvantages of an irregular education, a slighted authority, and a sickly constitution; he made himself master of the most eminent qualifications.

With an almost critical knowledge of the Greek and Latin languages, he understood and conversed in French, Spanish and Italian. He was well read in natural

philosophy, astronomy, and logic. He imitated his father in searching into the conduct of public men in every part of his dominions, and kept a register in which he wrote the characters of such persons, even to the rank of Justice soft he Peace. He waswell-informed of the value and exchange of money.

He is said to have been master of the theory of military arts, especially fortification; and was acquainted with all the ports in England, France, and Scotland, their depth of water, and their channels. His journal, recording the most material transactions of his reign from its very commencement, the original of which, written by his own hand, remains in the Cotton Library, proves a thirst for the knowledge not only of political affairs at home and of foreign relations, but of the laws of his realm, even to municipal and domestic regulations comparatively insignificant, which, at his was “This the age, truly surprising. “This child,” says famous Cardan, who frequently conversed with him, ” was so bred, had such parts, was of such expectation, that he looked like a miracle of a man; and in him was such an attempt of Nature, that not only England but the world had reason to lament his being so early snatched away.”

With these great endowments, which too frequently produce haughty and ungracious manners, we find Edward mild, patient, beneficent, sincere, and affable; free from all the faults, and uniting all the perfections, of the sovereigns of his family who preceded or followed him: courageous and steady, but humane and just; bountiful, without profusion; pious, without bigotry ; graced with a dignified simplicity of conduct in common affairs, which suited his rank as well as his years; and artlessly obeying the impulses of his perfect mind, in assuming, as occasions required, the majesty of the Monarch, the gravity of the statesman, and the familiarity of the gentleman.

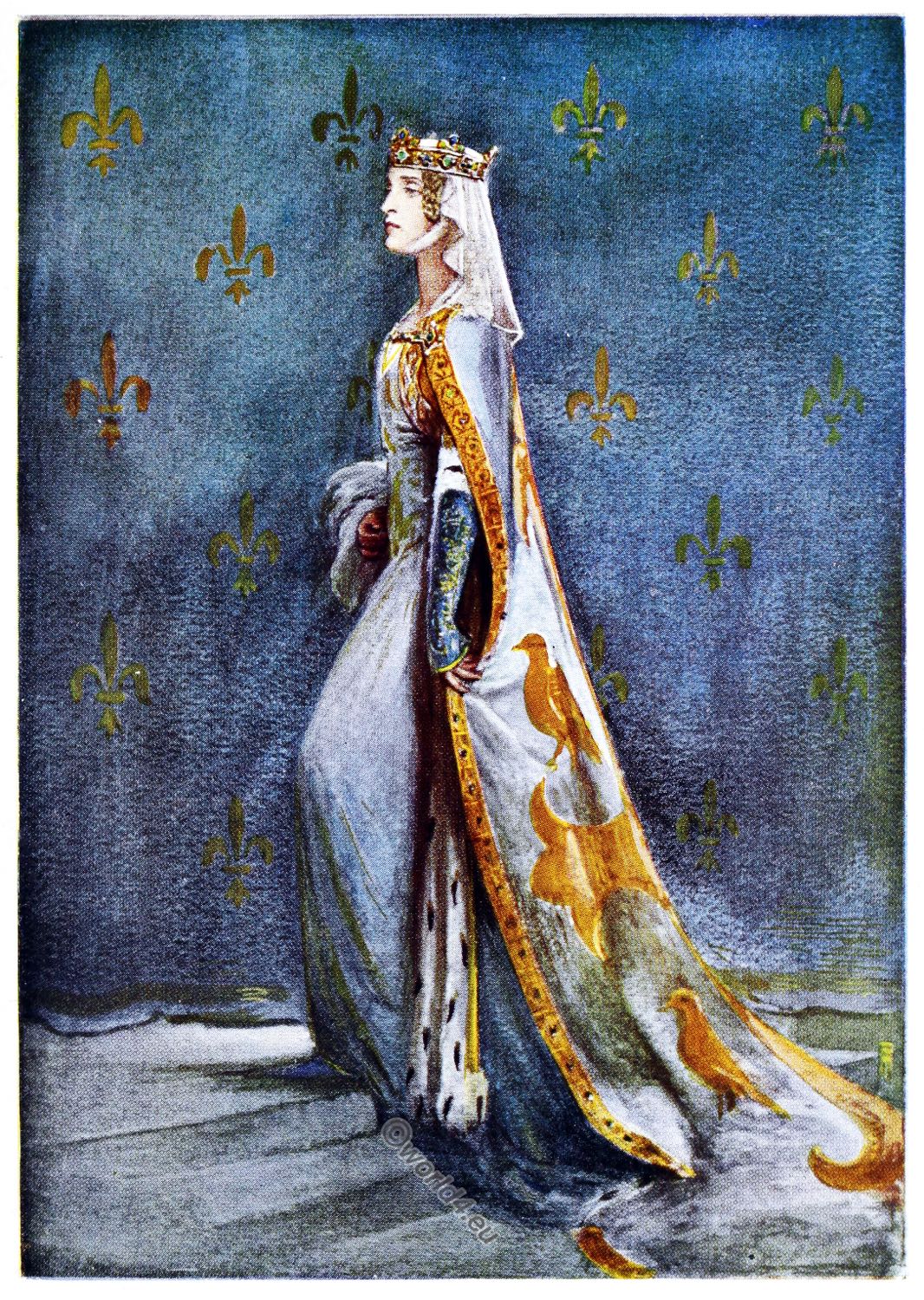

Such is the account invariably given of Edward the Sixth; derived from no blind respect for the memory of his father, whose death relieved his people from the scourge of tyranny; without hope of reward from himself, whose person never promised manhood; with no view of paying court to his successor, who abhorred him as an heretic, or to Elizabeth, whose title to the throne he had been in his dying moments persuaded to deny; but dictated solely by a just admiration of the charming qualities which so wonderfully distinguished him, and perfectly free from those motives to a base partiality, which too often guide the biographer’s pen when he treats of the characters of Princes. Concerning his person, Sir John Hayward informs us that “he was in body beautiful; of a sweet aspect, and especially in his eyes, which seemed to have a starry liveliness and lustre in them.” -This description is fully justified by the present copy of his portrait.

The Journal however kept by this regal child, which has been already slightly mentioned, is so highly illustrative of important parts of his character, and corroborates in so many instances the reports which we have derived from his eulogists, that it would be blameable to suffer these notices of him to go forth unaccompanied by a specimen at least of a document so extraordinary. We will take for this purpose, without any care of selection, his entries for the months of July and August, 1551, made when he was in his fourteenth year.

Edward in 1546, around his neck he wears a chain with the feather and the crown of the heir to the throne.

JULY.

“1. Whereas certain Flemish ships, twelve sail in all, six tall men of war, looking for eighteen more men of war, went to Diep, as it was thought, to take Monsieur le Marechal by the way, order was given that six ships being before prepared, with four pinnaces and a brigandine, should go, both to conduct him, and also to defend if any thing should be attempted against England by carrying over the Lady Mary. – 2. A brigandine sent to Diep, to give knowledge to Monsieur le Mareschal of the Flemings coming, to whom all the Flemings vailed their bonnet. Also the French Ambassador was advertised, who answered that he thought him sure enough when he came into our streams, terming it so.”

“2. There was a proclamation signed for shortening the fall of the money to that day, in which it should be proclaimed and devised that it should be in all places of the realm within one day proclaimed.”

“3. The Lord Clinton and Cobham was appointed to meet the French at Gravesend, and so to convey him to Duresme Place, where he should lie. – 4. I was banqueted by the Lord Clinton at Deptford, where I saw the Primrose and the Mary Willough by launched. The Frenchmen landed at Rye,as some thought for fear of the Flemings, lying at the Land’s End, chiefly because they saw our ships were let by the wind that they could not come out.”

“6. Sir Peter Meutas, at Dover, was commanded to come to Rye, to meet Monsieur le Mareschal, who so did; and after he had delivered my letters, written with mine own hand, and made my recommendations, he took order for horses and carts for Monsieur le Mareschal, in which he made such provision as was possible to be for the sudden. – 7. Monsieur le Mareschal set forth from Rye, and in his journey Mr. Culpepper, and divers other gentlemen, and their men, to the number of 1000 Horse, well furnished, met him, and so brought him to Maidstone that night.”

“7. Removing to Westminster.

“8. Monsieur le Mareschal came to Mr. Baker’s, where he was well feasted and banqueted.”

“9. The same came to my Lord Cobham’s to dinner, and at night to Gravesend. Proclamation was made that a testourn should go at 9d and a at 3d in all of the, places, groat realm at once. At this time came the sweat into London, which was more vehement than the old sweat; for if one took cold he died within three hours; and if he escaped it held him but nine hours, or ten at the most: also if he slept the first six hours, as he should be very desirous to do, then he roved, and should die roving.”

“11. It grew so much; for in London the 10th day there died 100 in the liberties, and this day 120; and also one of my gentlemen, another of my grooms, fell sick and died; that I removed to Hampton Court, with very few with me.

The same night came the Mareschal, who was saluted with all my ships being in the Thames, fifty and odd, all with shot well furnished, and so with the ordnance of the Tower. He was met by the Lord Clinton, Lord Admiral, with forty gentlemen, at Gravesend, and so brought to Duresme Place. – 13. Because of the infection at London he came this day to Richmond, where he lay, with a great band of gentlemen, at least 400, as it was by divers esteemed, where that night he hunted.”

“July 14. He came to me at Hampton Court at nine of the clock, being met by the Duke of Somerset at the wall-end, and so conveyed first to me; where, after his Master’s recommendations and letters, he went to his chamber on the Queen’s side, all hanged with cloth of Arras, and so was the hall, and all my lodging. He dined with me also. After dinner, being brought into an inner chamber, he told me he was come, not only for delivery of the Order, but also for to declare the great friendship the King his master bore me, which he desired I would think to be such to me as a father beareth to a son, or brother to brother; and although there were divers persuasions, as he thought, to dissuade me from the King his master’s friendship, and witless men made divers rumours, yet he trusted I would not believe them: furthermore, that as good ministers on the frontiers do great good, so ill much harm; for which cause he desired no innovation should be made on things had been so long in controversy by hand-strokes, but rather by commissioners’ talk. I answered him that I thanked him for his order, and also his love, &c. and I would shew love in all points. For rumours, they were not always to be be believed; and that I did sometime provide for the worst, but never did any harm upon their hearing. For Ministers, I said, I would rather appease these controversies with words than do any thing by force. So after, he was conveyed to Richmond again.”

“17. He came to present the Order of Monsieur Michael, where, after with ceremonies accustomed he had put on the garments, he and Monsieur Gye, likewise of the Order, came, one at my right hand, the other at my left, to the Chapel; where, after the Communion celebrated, each of them kissed my cheek. After that they dined with me, and talked after dinner, and saw some pastime, and so went home again.”

“17. This day my Lord Marquess and the commissioners coming to treat of the marriage, offered, by later instructions, 6OO’OOO crowns; after, 400’000; and so departed for an hour. Then, seeing they could get no better, came to the French offer of 200’000 crownes, half to be paid at the marriage, half six months after that. Then the French agreed that her dote should be but lO’OOO marks of lawful money of England. Thirdly, it was agreed that if I died she should not have the dote, saying they did that for friendship’s sake, without precedent.”

“18. A proclamation made against regraters and forestallers, and the words of the statute recited, with the punishment of the offenders. Also letters were sent to all officers and sheriffs for the executing thereof.”

“19. Another proclamation made for punishment of them that would blow rumours of abasing and enhancing of the coin, to make things dear withal. The same night Monsieur le Mareschal St. André supped with me: after supper saw a dozen courses; and, after, I came, and made me ready.”

“19. The Scots sent an Ambassador hither for receiving the treaty, sealed with the Great Seal of England, which was delivered him. Also I sent Sir Thomas Chaloner, clerk of my council, to have the seal of them, for confirmation of the last treaty, at Northampton.”

“20. the next morning, he came to me to mine arraying, and saw my bedchamber, and went a hunting with hounds, and saw me shoot, and saw all my guards shoot together. He dined with me; heard me play on the lute; ride; came to me to my study; supped with me; and so departed to Richmond.”

“19. The Lord Marquess having received and delivered again the treaty, sealed, took his leave, and so did all the rest. At this time there was a bickering at Parma between the French and the Papists : for Monsieur de Thermes, Petro Strozzi, and Fontivello, with divers other gentlemen, to the number of thirty, with fifteen hundred soldiers, entered Parma. Gonzaga, with the Emperor’s and Pope’s band,lay near the town. The French madesallies, and overcame, slaying the Prince of Macedonia, and the Signor Baptista, the Popes nephew.”

“22. Mr. Sidney made one of the four chief gentlemen.”

“23. Monsieur le Mareschal came to me, declaring the King his master’s well-taking my readiness to this treaty, and also how much his master was bent that way. He presented Monsieur Bois Dolphine to be Ambassador here, as my Lord Marquess the 19th day did present Mr. Pickering.

“26. Monsieur le Mareschal dined with me; after dinner saw the strength of the English archers. After he had so done, at his departure I gave him a diamond from my finger, worth by estimation 150′, both for pains, and also for my memory. Then he took his leave.”

“27. He came to a hunting to tell me the news, and shew me the letter his master had sent him; and doubtless of Monsieur Termes’ and Marignan’s letters, being Ambassador with the Emperor.”

“28. Monsieur le Mareschal came to dinner in Hyde Park, where there was a fair house made for him, and he saw the coursing there.”

“30. He came to the Earl of Warwick’s; lay there one night; and was well received.”

“29. He had his reward, being worth 3000′. in gold, of current money; Monsieur de Gye, 1000; Monsieur Chenault, 1000; Monsieur Movillier, 500′; the Secretary, 500′; and the Bishop of Peregrueux, 500.”

AUGUST.

“3. Monsieur le Mareschal departed to Bologne, and had certain of my ships to conduct him thither.”

“9. Four and twenty Lords of the Council met at Richmond, to commune of my sister Mary’s matter: who at length agreed that it was not meet to be suffered any longer; making thereof an instrument, signed with their hands, and sealed, to be on record”

“11. The Lord Marquess, with the most of his band, came home, and delivered the treaty sealed.”

“12. Letters sent for Rochester, to come the 13th but day, came and not till another letter was sent to them the 13th day.”

“14. My Lord Marquess’s reward was delivered at Paris, worth 500′; my Lord of Ely’s, 200′; and Mr. Hobbey’s, 150′; the rest, all about one scantling. Rochester, &c. bad commandment neither to hear, nor to suffer, any kind of service but the common and orders set for that large by Parliament; and had a letter to my Lady’s house from my Council for their credit; another to herself from me. Also appointed that I should come and sit at Council when great matters were debating, or when I would. This last month Monsieur de Termes, with 500 Frenchmen, came to Parma, and entered safely: afterwards, certain issued out of the town, and were overthrown; as Scipiaro, Dandelot, Petro, and others were taken, and some slain: after, they gave a skirmish ; entered the camp of Gonzaga, and spoiled a few tents, and returned.

“15. Sir Robert Dudley and Barnabe” sworn two of the six ordinary gentlemen. The last month the Turks’navy won a little castle in Sicily.”

“17. Instructions sent to Sir James Croftes for divers purposes, whose copy is in the Secretary’s hands. The Testourn cried down from 9d to 6d; the groat from 3d to 2d; the 2d to 1d; the penny to a halfpenny; the halfpenny to a farthing, &c.

“1. Monsieur Termes and Scipiero overthrew three ensigns of horsemen at three times; took one dispatch sent from Don Fernando to the Pope concerning this war, and another from the Pope to Don Fernando ; discomfited four ensigns of footmen; took the Count Camillo of Castilion ; and slew a captain of the Spaniards.”

“22. Removing to Windsor.”

“23. Rochester, &c. returned, denying to do openly the charge of the Lady Mary’s house, for displeasing her.”

“26. The Lord Chancellor, Mr. Comptroller, the Secretary Petre, sent to do the same commission.”

“27. Mr. Coverdale made Bishop of Exeter.”

“28. Rochester, &c. sent to the Fleet. The Lord Chancellor, &c. did that they were commanded to do to my sister, and her house.”

“31. Rochester, &c. committed to the Tower. The Duke of Somerset, taking certain that began a new conspiracy for the destruction of the gentlemen at Okingham, two days past executed them with death for their offence.”

“29. Certain pinnaces were prepared to see that there should be no conveyance over-sea of the Lady Mary secretly done. Also appointed that the Lord Chancellor, Lord Chamberlain, the Vice-chamberlain, and the Secretary Petre, should see by all means they could whether she used the Mass; and if she did, that the laws should be executed on her chaplains. Also that when I came from this progress to Hampton Court or Westminster, both my sisters should be with me till further order were taken for this purpose.”

As no apology may perhaps be necessary either for the matter or the extent of these extracts, I will venture to close the tribute thus irregularly collected and devoted to the memory of this Prince with two additional documents of some curiosity; the first, a paper addressed to some unknown person, all written with his own hand, with which I have been just now favoured by an ingenious friend, who transcribed it from the original in the Ashinolean collection at Oxford.

It is clear that it may be referred to the great and tragical discord between the Protector and his brother, and that the innocent Edward, then but at the age of ten years, had been called on to disclose the matters adverse to the Protector which had passed in his conversations with the Admiral, in order that they might be used as evidence against that nobleman. The connection of the paper with the history of Edward seems to confer some value on it, nor is it without marks of the premature sagacity which distinguished him.

“Sr. The Lord Admirall cam to me at the last parliament, and desired me to wryght a thyng for him. I asked him what? He sayd it was non ille; it is for the Quene’s maters.’ I sayd if it were good the Lordes wold allow it: if it were ill, I wol not wright in it. Then he sayd he wold take in better part if i wrought. I desired him to let me alon. I asked Chek whether it wer good to wright, and he sayd no.

He sayd “w’in this tow yere at lest ye must take upon yow to be as ye are, or ought to be, for ye shall be able, and then yow may give your men somwhat; for your unkle is old, and it rust wil not live long.” I say dit wer better for him to die befor. He sayd “ye ar a begagarly King. Ye have no monie to pay or to geve.” I sayd that Mr. Stanhop had for me. Then he sayd that he wold geve Fouler; and Fouler did geve the monie to divers men as I bad him; as to Master Chek, and the bokbinder, and other. He told me thes thinges often times. Fouler desired me to geve thankes to my Lord

Admirall for his gentilnes to me, and praised him to me verie much.

E. R.

“In the moneth of September, An. D. 1547, the Lord Admirall told me that min unkle, beeing gon into Scotland, shuld notpasse the peese w’out losse of men, a great number of men, or of himself, and that he did spend much monie in vain. After the returne of min unkle he sayd that i was toe bashful in mi maters, and that I wold not speake for mi right. I sayd I was wel enoughe. When he went to his contré he desired me not to beleve men that wold sclaunder him till he cam himself.

E. R.

The second is an extract from the original draft of a letter from the Lords of the council to the English Ambassador at the Court of the Emperor, which may be found among the Cecil Papers in the Illustrations of British History, &c. disclosing some slight particulars of Edward’s final disease, which seems to have not been elsewhere described otherwise than generally.

“After of hrté comendations. We must nede be sorry now to write that which cometh both sorrowfully from us, and shall, we well knowe, w’. the like sorrowe be taken of yow; but, such is the almighty will of God in all his creations, that his ord’ in them may not be by us resisted. In one worde we must tell yow a greate heape of infelicité. God hathe called owte of this world of soveraigne Lord the vitb. of this moneth; whose mart of dethe was such toward God as assureth us his sowle is in the place of eternall joye, as, for yo owne satisfaction p~tly ye may p~ceve by the copye of the words which he spake secretly to hym selfe at the mome~t of his dethe. The desease whlof his Maty died was the desease of the longs, which had in them 11 grete ulceres, and were putrefied, by meanes whrof he fell into a consumption, and so hath he wasted, being utterly incurable. Of this evill, for the e~portance, we adv~tise you, knowing it most comfortable to have bene ignorant of it; and the same ye maye take tyme to declare unto the Emp~or as from us,” &c.

Source: Portraits of illustrious personages of Great Britain: engraved from authentic pictures in the galleries of the nobility and the public collections of the country : with biographical and historical memoirs of their lives and actions by Edmund Lodge (1756-1839). London: Harding and Lepard, 1835.

[wpucv_list id=”136569″ title=”Classic grid with thumbs 4″]