Hampton Court Palace is a castle in far south-west London on the left bank of the River Thames in the borough of Richmond upon Thames. The palace was a favourite residence of English and British kings from 1528 to 1737.

Originally built in the Tudor style, large parts were rebuilt in the English Baroque style towards the end of the 17th century and in the 18th century. With its huge dimensions, magnificent interior and extensive gardens, it is considered one of the major works of the Tudor style and Baroque in England.

HAMPTON COURT.

CHAPTER IV.

Hampton Court Palace – History of the Palace – The Gardens – The Vinery – Bushey Park.

GROSSING Hampton Bridge, and pausing to admire the beautiful view of the river, with its wooded eyots, which it commands, we duly arrive at the main | entrance to Hampton Court Palace. Away to the left stretches the Green, where, in the days of the Tudors and the Stuarts, much “tilting” was carried on; and where, in the days of Victoria, London citizens and their families disport themselves according to the “sad” English fashion. In front of us, beyond a range of well-built houses, rise the green tops of the chestnuts and hawthorns of Bushey Park. It is needless to say that all round about the hanging signs proclaim an abundance of “entertainment for man and horse.” The inn known as the “the Toy” perpetuates the name (corrupted from the tois or toils, the network barriers used in the tilting-games), but does not occupy the site, of the ancient hostelry, where William “the Deliverer” was accustomed to entertain his cavaliers with dinners of rump-steak, washed down by Dutch “schnapps,” and enveloped in clouds of fragrant tobacco smoke.

A solid wall of red brick separates the Palace-grounds from the Green; and in front of this wall runs a broad walk, lined by elm and chestnut, which Queen Mary and her maids of honour much frequented. Their constant resorting to it led to its being popularly known as the Fran—since strangely corrupted into Frog—walk. The Palace entrance is duly distinguished by the royal arms. To the right extends a range of offices, and, opposite, the long line of the cavalry barracks, with the usual appurtenances. Both are wholly unworthy of their situation, and absolutely degrade the approach to the Palace. The contrast which they present to the well-proportioned gateway tower, erected by Wolsey, is at once startling and suggestive.

The manor of Hampton formerly belonged to the Knights Hospitallers of St. John of Jerusalem, from whom it was leased by Archbishop of York, Thomas Wolsey, for the purpose of erecting on the site of the old manor-house a palace worthy of his fortunes. In 1515 he began to realise his design, and with such vigour and energy did he push forward the works that he was soon able to take up his residence there. The plan was conceived on a magnificent scale, and the details were all in keeping with it. In truth, the splendour of the new building, and the sumptuous state which the great Cardinal maintained in it, soon awakened the jealousy of Henry VIII., and Wolsey found it advisable to propitiate his royal master by presenting him with the Palace and all it contained. The gift was immediately accepted, and in acknowledgment of it Henry licensed the Cardinal to occupy the Royal Palace at Richmond whenever he pleased, and occasionally permitted him to retire to Hampton Court itself.

Hampton Court quickly became Henry VIII’s new favourite residence. The King made large additions to the Palace— “till it became more like a city than a house;” and these (especially the Great Hall) were conceived in a spirit not inferior to Wolsey’s. In just ten years, he spent the enormous sum of £62,000 – about £18 million in today’s value – on the castle. When the work was completed around 1540, it was considered one of the most magnificent and modern castles in England. All six of Henry’s wives lived in the palace and were each given elaborately designed flats. Henry had his own living quarters rebuilt and renovated at least six times. In addition, there were living quarters for his children and for a large number of courtiers, guests and servants.

To secure the necessary seclusion, as well as entertainment, he cleared the surrounding country of inhabitants and stocked it with deer, extending the “Honour,” or demesne, for miles around, so that it included Cobham, Weybridge, Byfleet, the two Moleseys, Esher, and Ditton. He appears to have been very partial to this beautiful river-side retreat. It was here that he received the intelligence of Wolsey’s death. Here, in 1531, Anne Boleyn, as Queen, was the central figure in every revel, banquet, and pastime. Queen Jane Seymour died here, shortly after giving birth to Edward VI. (1537).

The young Prince was brought up at Hampton with a vast degree of care. “It was commanded,” says Froude, “that no person, of what rank soever, except the regular attendants in the nursery, should approach the cradle without an order under the King’s hand. The food supplied for the child’s use was to be largely ‘assayed.’ His clothes were to be washed by his own servants, and no other hand might touch them. The material was to be submitted to all tests of poison. The chamberlain or vice-chamberlain must be present, morning and evening, when the Prince was washed and dressed; and nothing of any kind, bought for the use of the nursery, might be introduced till it had been aired and perfumed. No person—not even the domestics of the palace might have access to the Prince’s rooms, except those who were specially appointed to them; nor might any member of the household approach London during the unhealthy season, for fear of their catching and conveying infection.”

Here, on July 2nd, 1543, Catherine Parr was married and proclaimed Queen; and here, at one of Henry’s gorgeous festivals, the poet-Earl of Surrey first saw, and loved, his Geraldine: “Hampton me taught to wish her first for mine.” The most famous was the six-day visit of the French ambassador in August 1546, when the palace hosted about two hundred guests in addition to Henry’s court of about 1300 people. For this purpose, the palace was surrounded by a magnificent tent camp.

After Henry’s death, the country folk petitioned the King’s Council for relief; and the Lord Protector Somerset ordered the Honour to be “dechased,” the deer to be killed or removed, and the land restored at the old rents to the old tenants.

Edward VI. frequently resided at Hampton Court. He was here in the late autumn of 1549, when his uncle, the Protector, informed the Council of the confederacy formed against himself under the leadership of the Earl of Warwick, and a hurried proclamation was issued, requiring all the King’s loving subjects “to repair to his Highness at his Majesty’s manor of Hampton Court, in most defensible array, with banners and weapons, to defend his most royal person and his most entirely beloved uncle, the Lord Protector, against whom certain had attempted a most dangerous conspiracy.” But the wheel of fortune swung round; Somerset fell; and at Hampton Court, in 1551, Edward created the Earl of Warwick Duke of Northumberland.

Queen Mary retired hither with her Spanish husband soon after their marriage, living in a seclusion that deepened the popular repugnance to the alliance. Here she received her sister, the Princess Elizabeth, and her confessors endeavoured to persecute the Princess into an abjuration of Protestantism. Elizabeth owed her life, apparently, to King Philip’s good offices; and in the Christmas festivities at the Palace in 1544, still through his good offices, she occupied her proper place “The Princess supped at the same table with the King and Queen, next the cloth of state; and after supper, was served with a perfumed napkin and plates of confects by the Lord Paget.” We also read: —” On St. Stephen’s Day she heard matins in the Queen’s closet adjoining to the chapel, where she was attired in a robe of white satin, strung all over with large pearls.

On the 29th day of December, she sate with their Majesties and the nobility at a grand spectacle of jousting, when 200 spears were broken. Half of the combatants were accoutred in the Almaine, and half in the Spanish fashion.” When Elizabeth became Queen she frequently visited Hampton Court, and it was beneath its roof she discussed with her lords the charge against Mary, Queen of Scots, of having conspired with Bothwell to murder Henry Darnley. Elizabeth I had some minor alterations carried out, including that of the eastern kitchen.

It was here, on the 4th of December, 1568, the Regent Murray produced the fatal casket. “The entire evidence was placed in the hands of the Council. . . . The casket was opened, and the letters, presents, and contracts were taken out and read. They were examined long and minutely by each and every of the lords who were present,” and declared genuine.

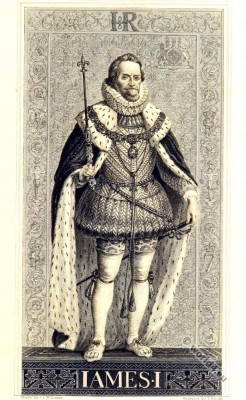

Here it was, in 1604, that James I. *), son of Mary Stuart, held the famous “Conference” of prelates and Puritan divines of the Anglican Church, for the discussion of the grievances alleged by the latter; a conference in which he made great display of his own theological learning, and when the Puritans ventured to dispute his conclusions, hastily threatened that he would make them conform, or would harry them out of the land. Under his chairmanship, the King James Bible, became the most influential translation of the Bible in English.

*) The first recorded fireworks display in Scotland took place on the occasion of its christening.

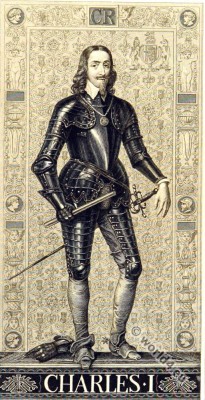

Jacob’s son and successor Charles I had some alterations made, including a new tennis court and new fountains in the garden. The brightest hours of the chequered life of Charles I.— those which he spent in the bosom of his family and the indulgence of his refined tastes—were passed at Hampton Court. Here he received the Ambassadors of France and Denmark, in July, 1625; here he knighted, in October, 1638, Balthazar Gerbier, the painter; hither, in January, 1642, he and his Queen retired from the insurrection in London, excited by his abortive attempt to arrest “the Five Members.”

Charles was also an avid art collector and acquired numerous paintings and sculptures by renowned artists. The most important of these acquisitions is the Triumph of Julius Caesar by Andrea Mantegna. This masterpiece of Renaissance painting, created around 1485, was bought from the Dukes of Mantua by order of the King in 1629 and brought to Hampton Court in 1630.

In August, 1647, he came to Hampton as a prisoner, and remained for three months under gentle supervision, carrying on negotiations with Cromwell and the Army which he never meant to bring to any definite issue. Lady Fanshawe visited him here —”I went three times,” she says, “to pay my duty to his Majesty, both as I was the daughter of his servant and the wife of his servant. The last time I ever saw him I could not refrain from weeping. He kissed me when we took our leave of him; and I, with streaming eyes, prayed aloud to God to preserve his Majesty with a long and happy life.

The King patted me on the cheek, and said, impressively, ‘Child, if God wiliest, it shall be so; but you and I must submit to God’s will, and you know what hands I am in.’ Then, turning to my husband, Sir Richard Fanshawe, he said, ‘Be sure, Dick, to tell my son all I have said, and deliver these letters to my wife. I pray God to bless her, and preserve her, and all will be well.’ Then taking my husband in his arms, he said, ‘Thou hast ever been an honest man! I hope God will bless thee, and make thee a happy servant to my son.’ Thus did we part from that benign light, which was extinguished soon after, to the grief of all Christians not forsaken of their God.”

Charles escaped from the Court on the night of the 11th of November, 1647, a night as dark and stormy as his fortunes, and made his way to the Hampshire coast, and so to Carisbrook Castle, in the Isle of Wight; a strange error, which threw him completely into the hands of his sternest opponents. He was taken to London and finally executed on 30 January 1649.

In 1656 the Palace was purchased by Cromwell, with whom, during the brief remainder of his life, it became a favourite residence. Here his daughter Elizabeth was wedded in the royal chapel to Lord Falconbridge, November 18, 1657; lost his well-loved daughter, Lady Claypole, August 6th, 1658; and here, a fortnight later, he was seized with the fever of which he died. “I met him,” says George Fox, the Quaker, “riding into Hampton Court Park; and before I came to him, as he rode at the head of his lifeguard, I saw and felt a waft of death go forth against him.”

Harvey, his Groom of the Bedchamber, writes, “At Hampton Court, a few days after the death of the Lady Elizabeth, which touched him nearly,” his Highness was “himself under bodily distempers, forerunners of that sickness which was to death.” On the 20th of August he was better: but next day, Saturday, a great change took place, and symptoms of tertian ague were observed. He returned to Whitehall on the following Tuesday, and on the 3rd of September passed away.

The Palace was not held in less esteem by Charles II., of whose diversions here the gossiping pages of Pepys, who walked from Teddington to see “the noble furniture and splendid pictures,” and the Chronique Scandalense of Count Grammont, afford some glimpses. Evelyn has left on record a graphic description of the Palace as it was in the summer of 1662 :— “It is as noble and uniform a pile, and as capacious, as any Gothic architecture can have made it.

Charles II, however, preferred Windsor Castle as a country residence and stayed less frequently at Hampton Court. However, he had a flat refurbished at the south-east corner of the palace for his mistress Barbara Villiers and his illegitimate children. These rooms, furnished in the Baroque style, were in complete contrast to the rooms furnished in the Tudor style.

There is incomparable furniture in it, especially hangings designed by Raphael, very rich with gold and also many rare pictures. Of the tapestries, I believe the world can show nothing nobler of the kind than the stories of Abraham and Tobit.

The gallery of horns is very particular for the vast beams of stags, elks, antelopes, etc. The Queen’s Bed was an embroidery of silver on crimson velvet, and cost £8000, being a present made by the States of Holland when his Majesty returned, and had formerly been given by them to our King’s sister, the Princess of Orange, and, being bought of her again, was now presented to the King. The great looking-glass and toilet, of beaten and massive gold, was given by the Queen-mother. The Queen brought over with her from Portugal such Indian cabinets as had never before been seen here.

The Great Hall is a most magnificent room; the chapel roof excellently fretted and gilt. I was also curious to visit the wardrobes and tents, and other furniture of state; the park, forming a fiat naked piece of ground, and planted with sweet rows of lime trees; and the canal for water, now near perfected; also the hare park. In the garden is a rich and noble fountain, with sirens, statues, etc., cast in copper by Favelli, but no plenty of water. The cradle-walk of hornbeam in the garden is, for the perplexed twining of the trees, very observable.”

A not less glowing picture than this is drawn by Catherine of Braganza’s Portuguese historian, who also describes the balls and revels, and the river pageants, and the open-air pastimes that made the Palace gay.

It was the English “home” of William III. *), who nowhere else in England could reproduce so nearly the conditions of his court on the Hague. He loved the placid flow of the broad river; the murmur of the reeds and sedges that lined its banks; the pleasant formality of the level gardens that extended in front of the Palace; the shade of elm and chestnut, arranged in leafy groups or noble avenues. Here he built and planted; the Maze, the Wilderness, and the Gardens were laid out by his direction. Here, too, on the 20th of February, 1702, while he was riding in the Park, his favourite horse, Sorrel, struck his foot against a mole-hill, and, stumbling, threw his rider. On taking him up, his attendants found that he had broken his collar bone, and he was removed to Kensington—to die.

*) William III of Orange (4 November 1650 – 8 March 1702) from the House of Orange-Nassau was Governor of the Netherlands from 1672 and King of England, Scotland and Ireland in personal union from 1688 until his death. In 1688/1689, after a successful invasion in the course of the Glorious Revolution, the Prince of Orange succeeded to the British throne together with his wife Mary II, which he held alone after her death. As King of Scotland, he was William II. William of Orange was the decisive opponent of the French “Sun King” Louis XIV. He saw his main task as uniting the Protestant powers of Europe and rejecting France’s hegemonic claims. Under his rule, England, the Netherlands and the Roman-German Empire waged wars against the superiority of France that lasted for decades.

Queen Anne was not less partial to the court than her predecessor; *) and its state as a royal palace was fully maintained by the First and Second Georges. Then its glory began to decay. The Third George affected Kew, and the Fourth George restored Windsor Castle. So it came to pass that the fierce light which beats upon a throne ceased to illuminate Hampton Court ; and while the Hall and State apartments were thrown open freely for public inspection, the other portions were formed into residences at the disposal of the Sovereign, which are usually allotted to the widows and families of military officers of high repute but narrow means.

*) “Here thou, great Anna! whom these realms obey,

Dost sometimes counsel take—and sometimes tea

Hither the lovers and the nymphs resort,

To taste awhile the pleasures of a Court.” Pope.

Of the five quadrangles which originally composed the Palace only three remain *). The third, or Fountain Court, was built by Sir Christopher Wren for William III., but exhibits few signs of his great architectural genius. Perhaps he was cramped by that lack of funds of which Queen Mary complains in a letter to her royal consort : —”I hear of so much use for money, and find so little, that I cannot tell whether that of Hampton Court will not be the worst for it.”

*) The multiform façade from the Tudor period with numerous towers and chimneys was replaced by a large, elegant Baroque façade, which dominates the garden view of the castle to this day. Magnificent parade rooms were created in the castle, furnished by the best artists in England at the time, and the gardens were also redesigned as Baroque gardens. Numerous new plants, including many exotic ones from Queen Mary’s collection, enriched the gardens.

During the work of reconstruction the King and Queen resided in “the Water Gallery,” a portion of which, the banqueting-room, is still in existence. The original character of the first, or Outer Court, and the second, or Clock Court, *) has not been seriously modified; though the pseudo-classic additions to these second Court and to Henry VHP’s Hall are not improvements. Some years ago the Great Hall was carefully restored, and alcoved windows, “blushing with scutcheons,” were introduced, from designs by the English stained glass artist Thomas Willement, called “the father of Victorian stained glass”.

*) The Fountain Court measures 110 feet by 167; the Western, or Outer Court, 167 feet by 161; and the Middle, or Clock Court, 133 feet by 92 feet.

**) It measures 106 feet long, 40 feet wide, and 60 feet high.

His successor Anne came to hunt at Hampton Court despite her failing health, but her main residences were Windsor Castle and Kensington Palace, so that further interior work on the castle stalled. It was not until George II, as Prince of Wales, showed renewed interest in the castle and had John Vanbrugh complete the parade rooms. After his accession to the throne, George II and his wife Caroline again lived more frequently at Hampton Court after 1727, where they had some of the rooms refurbished. After the rift with his eldest son Frederick Louis and the death of his wife, the king and his court left Hampton Court Palace in 1737.

Few nobler apartments are to be found in England. The harmony of the proportions, the majestic sweep of the lofty open roof, the general air of grandeur and dignity, combined with the pomp of banners, and the rich hangings of ancient tapestry, and the gleaming groups of armour, produce a powerful effect on the imagination. It is like a chapter taken out of an old chronicle and set bodily before us. It recalls the pageantry and chivalrous circumstances of the past its brightest and most picturesque side—as nothing else can.

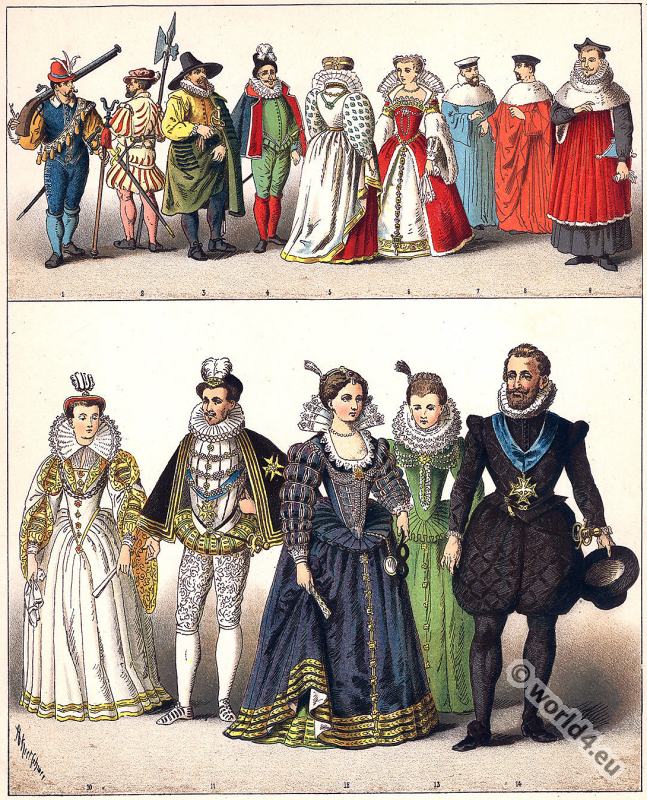

At once we people it with the men and women of the old time — with Henry VIII. and his courtiers, or with Charles I. and his family; or we see the great Lord Protector pacing it slowly, with his mind intent upon the grave concerns of the nation he ruled with so strong a hand. It furnishes a vivid commentary upon English history, when we remember how many generations of our Kings have fluttered through their brief day of splendour beneath this stately roof.

Hawthorne, the American novelist, describes the Hall as “a most noble and beautiful room, about a hundred feet long, and sixty high and broad. Most of the windows,” he adds, “are of stained or painted glass, with elaborate designs. The walls, from the floor to perhaps half their height, are covered with antique tapestry, which, though a good deal faded, still retains colour enough to be a very effective ornament, and to give an idea of how rich a mode of decking a noble apartment this must have been. The subjects represented were from Scripture, and the figures seemed natural.

On looking closely at this tapestry, you would see that it was thickly interwoven with threads of gold, still glistening. The windows, except one or two that are long, do not descend below the top of this tapestry, and are, therefore, twenty or thirty feet above the floor; and this manner of lighting a great room seems to add much to the impressiveness of the enclosed space. The roof is very magnificent, of carved oak, intricately and elaborately arched, and still as perfect to all appearance as when it was first made. There are banners—so fresh in their hues, and so untattered, that I think they must be modern suspended along beneath the cornice of the Hall, and exhibiting Wolsey’s arms and badges. On the whole, this is a perfect sight in its way.”

The tapestry here is Flemish, and represents the history of Abraham, in eight compartments. That at the entrance is of earlier date, and of the school of Albert Durer the subject, Justice and Mercy pleading before Kings. In the withdrawing-room, which measures seventy feet long by twenty-five feet high, the tapestry is covered with mythological designs. This apartment contains some cartoons of Carlo Cignani, and a marble statue of Venus.

By the King’s Staircase, over the walls and ceilings of which sprawl Verrio’s unmeaning allegories, we ascend to the apparently interminable suite of the State Apartments. These are mainly wainscoted with oak, dating from William III.’s reign. Around the panels and over many of the doorways may be seen some of that wonderful wood-carving by Grinling Gibbons, in which fruit, and foliage, and wreaths of flowers are represented with a delicacy and an exactness that have never been surpassed.

The apartments open one beyond another in a succession apparently as interminable as the line of Banquo, so that to traverse the whole of them is almost a day’s journey, and leaves a confused and bewildering impression on the mind. There are King’s drawing-rooms and Queen’s drawing-rooms, King’s bedchambers and Queen’s bedchambers, King’s closets and Queen’s closets, besides audience-chambers and the like.

We have no space to enumerate the pictures with which every wall is covered pictures good, bad, and indifferent. In Italian canvases the collection is specially rich, but there are good specimens of every school. It is to be regretted that they are not arranged on some intelligible principle, and in such a way as to contribute to the art-education of the thousands who visit the Palace.

Almost every room has some article of upholstery of the time of William, Anne, or George—such as Queen Anne’s State Bed, and William and Mary’s, which is worth a more or less cursory glance—and each commands from its windows a fine view of the gardens, sparkling with flowers and fountains, of the broad calm river, and the green Surrey hills beyond. “It is one of the pleasantest things in a visit here,” says Thorne, “to sit a while, if the room be not crowded, in one of these window-seats, and let the eye, which is growing fatigued with dwelling so long on the gaud and glitter of art, refresh itself by resting on the soft verdure and gentle features of nature.”

Let us now pass into the Gardens. They are of considerable size, and admirably kept. In Queen Elizabeth’s time, Hentzner describes them as being “most pleasant.” In Charles II.’s they were laid out anew by the royal gardener, Rose, in the then popular French taste; but their present arrangement is mainly due to the Dutch proclivities of William III., who employed Loudon and Wise to carry out his designs.

We confess that to us there is something very agreeable in their trim preciseness. It preserves the old-world character of the scene, and harmonises fitly with the quaint attitude of the Palace itself. It seems impossible not to be delighted by the long lines of noble trees, the broad straight walks, the “pleached alleys,” the glossy bowers, the soft smooth lawns, the shining columns of leaping water, and the parterres brimming over with bright colour.

The garden-front of the palace is Wren’s, and when viewed in connection with the walks and terraces becomes respectable. Opposite to its very centre is situated a fountain, with a large circular basin, in which gold and silver fish display their glancing hues; this is a good point from which to obtain a general view of the Palace and Gardens.

The Gardens extend from Bushey Park to the river. Also extending to the river, and in front of the Palace, lies the Home Park, where the artist’s eye will find pleasure in some noble trees. The private garden is not less worth a visit. Observe, on the left, the quaint old pleasaunce, sole relic of the Elizabethan mansion-house; it forms a rectangular oblong, and glows with the poets’ old-fashioned flowers—with rose, and clove, and pink, and stock, and lavender—just as it did when the Knights Hospitallers sunned themselves on its terraces.

Observe, too, the glossy hedge of evergreen which fences this lovely walk from the bitter East. A never-failing attraction to visitors is the Vinery, with the well-known “vine,” a Black Hamburg, which covers a surface of no feet or more, and has grown no fewer than 1750 splendid bunches of grapes in a season. It was planted in 1769; its stem is 30 inches in circumference. The average yearly produce is 1500 bunches. Reference must finally be made to the Wilderness, which is closely set with magnificent trees ; and to the Maze, an evergreen labyrinth, situated at the farther extremity.

Surely this brief sketch is sufficient to extort from the reader some such admission as that of Hawthorne’s:—”What a noble palace, nobly enriched, is this Hampton Court!” The American continues:—”The English Government does well to keep it up, and to admit the public freely into it for it is impossible for even a Republican not to feel something like awe—at least, a profound respect—for all this state, and for the institutions which are here represented ; the Sovereigns, whose usual magnificence demands such a residence; and its permanence, too, enduring from age to age, and each royal generation adding new splendours to those accumulated by their predecessors.”

Leaving by the Lion Gate, we cross the road into Bushey Park, a beautiful sylvan demesne, finely planted with grand old trees, the trunks of which are grown with moss, and traversed from end to end by William III.’s chestnut avenue—a thing of glory, unequalled and indescribable in its season of bloom.

The Park is said to take its name from its abundance of hawthorn. It is a tall times of the year a place to see and admire but it wears its chief splendour in that delightful period—half-May, half-June- “Half-prankt with spring, with summer half-imbrown’d,” when its hawthorns are alive with flowers, and its limes load the air with fragrance, and its mile-long avenue (planted by William III.) of horse-chestnuts breaks into flowery pyramids.

A sight to enjoy and to remember is the mass of pink and white blossom clustered on either side of the drive, which, on “Show Sunday,” or “Chestnut Sunday,” rivals Hyde Park, in the “season,” with its almost interminable procession of carriages. He who then visits Bushey Park will enjoy an intellectual feast as great as if he were suddenly transferred to

“Boccaccio’s garden and its faery,

The love, the joyaunce, and the gallantry;”

and taking it in connection with “royal Hampton’s pile,” will feel constrained to admit that a day thus spent deserves henceforth to be marked with a white stone; to be included among those few memorable days of which the mind desires to preserve the recollection until the very last.

Source: Our native land: new series: Windsor Castle and the water-way thither by Adams, (William Henry Davenport), 1828-1891; Jones, Frederick, fl. 1867-1885, ill. ill; Pritchett, R. T., ill. ill. London: Marcus Ward & Co., 1880.

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.