Fashion in Paris and London, 1780 to 1788.

LEGHORN CHIPS – THE ABOLITION OF THE HEAD-DRESS – THE CAUSES THAT BROUGHT IT – HAIR RESTORED TO ITS NATURAL STATE – HATS WITH IMMENSE BRIMS – THE DISAPPEARANCE OF THE HEAD-DRESS – THE ORIGIN OF THE HOOPED SKIRT – THE DISAPPEARANCE OF THE HOOPED SKIRT

THE LEGHORN CHIPS

Hats of foreign make, and known as “Leghorn Chips,” were imported from Italy, and what had started as a mere caprice in fashion, gradually developed into one of the most important industries of the world. In the meantime an agitation which had been brewing for some time now threatened to bring about a most important revulsion in feminine fashion.

This was in favor of the abolition of the head-dress, that towering mass of powdered hair which had for many years been considered the very acme of attractiveness by women of fashion. For some time it had been known that the building up of these head-dresses necessitated the use of animal wool and other substances which have a tendency after a time to develop certain unpleasant conditions.

The dressing of the hair in this fashion being a lengthy and costly process, it followed that it was not indulged in oftener than possible, and it, therefore, frequently happened that a lady’s head was not dressed or “opened” (this was the term used) more than once in two months, with a result that needs no description.

This disgusting condition of affairs would, one imagines, have sufficed for an excuse if one had been necessary to condemn the head-dress, but it remained in vogue notwithstanding until 1785, when, in obedience to the dictates of fashion as personified by the ladies of the Court of the Tuileries, its abolition was decreed. The causes that brought about the ultimate disappearance of the most extravagant and unsightly method of dressing the hair ever devised by civilised beings have been variously explained, but that they emanated from France is undisputed.

According to some writers, an instinctive premonition of the approaching cataclysm, when any one bearing the remotest resemblance to the hated aristocracy would be a marked person, prompted the abandonment of so distinctive a mode, whilst others state that the welcome disappearance of the odious fashion was brought about through the influence of the great painters of the day, who were also said to have been instrumental in sweeping away other follies of the times. It seems, however, far more probable that the passing away of the head-dress was but an instance of the fickleness of feminine fashion, actuated perhaps in no small degree by the serious political and social troubles which were threatening the country.

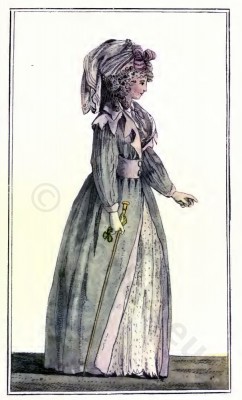

The hair henceforth was once more restored to its native state, and, dressed without powder, was allowed to fall in curls on the shoulders; hats with immense brims came into favor, and contributed to impart a picturesque and natural effect which had been long missing. The era of the head-dress with all its attendant barbarisms was at an end, and it may be safely conjectured never to return, whatever the evolutions of fashion. As might have been expected, the hooped skirt did not long survive the head-dress in France, although curiously enough it long afterwards remained the Court dress in England.

Fashion in London 1788

Fashion was in one of its most callous moods, and the infection of it spread even to London. Between the years of grace 1780 and 1785, as though in coincidence with the state of affairs in Paris, female dress in the fashionable world of London reached its zenith of profuse expenditure and absurdity, and was the subject of endless caricature and satire by contemporary wits, as for instance the following sample of the peculiar humor of the age:

” Give Betsy a bushel of horse-hair and wool. Of paste and pomatum a pound, Ten yards of gay ribbon to deck her sweet skull. And gauze to encompass it round.

” Of all the bright colors the rainbow displays Are those ribbons which hang from her head ; And her flounces are adapted to make the folks gaze. And around the work are they spread.

” Her cap flies behind for a yard at the back. And her curls meet just under her chin; And those curls are supported to keep up the jest With a hundred instead of one pin.

” Her gown is tucked up to the hip on each side ; Shoes too high for to walk or to jump, And to deck the sweet creature complete for a bride. The Cork-cutter cut her a Rump.

“Thus finished in taste while on her I gaze, I think I could take her for life. But I fear to undress her, for out of her stays, I shall find I had lost half my wife.”

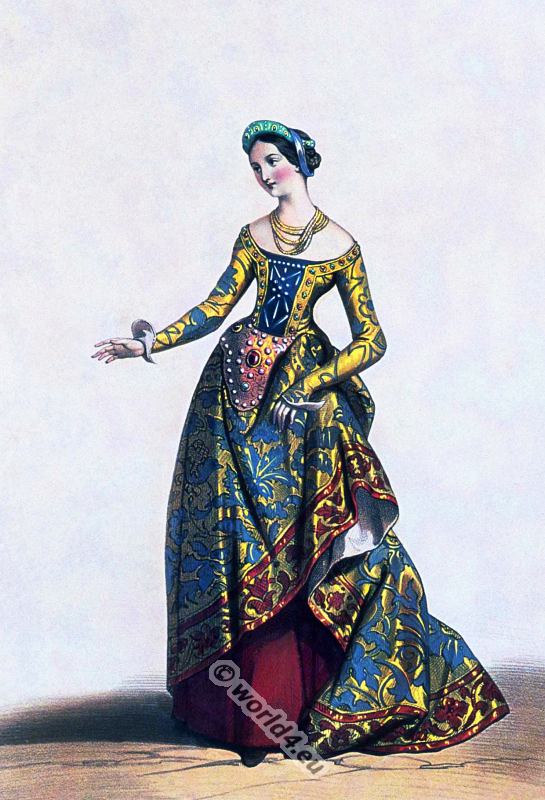

For forty years costume had been passing through peculiar stages of grotesque and unlovely development. The hooped skirt, a revival of the mode of the time of Queen Elizabeth, was the height of the fashion in England and France, and emulated and even surpassed in its inelegance the most outrageous styles of the Middle Ages, with none of their picturesqueness. To such an extent did the ridiculous fashion monopolise the attention not only of the followers of fashion, but the ordinary citizen, that we find serious London journals of the period giving long and almost scientific dissertations on the subject, whilst many also were the quaint arguments raised in the fashionable papers for and against the ‘* Hoop,” as it was popularly named.

The origin of the hooped skirt.

The origin of the cognomen, and the curious thesis propounded by one writer in particular, are worth repeating. “Hoops,” he says, “are of much greater antiquity than is generally supposed. They were first worn by the Greeks and Romans. When Queen Elizabeth donned a hoop it was called a ‘Farthingale.’

It gave rise, we are told, to scandal, but to keep her Majesty in countenance the whole Court assumed big bellies, which soon became the general pink of the mode. When innovations of any kind are introduced it is very difficult to know to what degree they may be carried. This has been the fate of this very petticoat, which from its circumference originally took the name of a ‘Hoop,’ but which, at present extending itself into a wide oblong form, has nothing but its name left of the familiar ‘Hoop.’

When we consider what alterations have been made in the lower part of the female dress, and think of the different figures which our great-grandmothers made with their petticoats clinging about their feet from the ladies’ spreading coats of the last age, it admits of a dispute whether the old habit was more modest, or the modern more polite.”

It is manifest that the controversy on this delicate subject was of no ordinary character. In fact at one time it amounted almost to an agitation in favor of the revival of the clinging petticoats which had been so strangely superseded.

Convex populo

Many curious and quaint reasons were on the other hand put forward in support of the retention of the “Hoop”: in one, for example, which strikes one as being particularly original, the writer of the argument remarks that the circular hoop gave the feet a freedom of motion showed the beauty of leg and feet which played beneath it, and gained admirers when the face was too homely to attract the heart of any beholder.

Another polite defender of the “Convex populo,” as it had been jestingly named, stated that he had observed in its favor that it served to keep men at a proper distance, and that a lady within its circle seemed to govern as in a reserved enclosure, sacred to herself: a somewhat fanciful description of a skirt, to which in reply it was pointed out very tersely by probably some cynical misogynist that it was well known that many ladies who wore hoops of the greatest circumference were not always of the most impregnable virtue. There were not wanting indications that the end of the particularly graceless mode was at hand, and so events proved, as will be seen.

Whilst the warfare between the “Hoopists” and the “Petticoatists” was proceeding, something new in the shape of a “novelty” diverted the attention of the fashionable world in England from the controversy. This new attraction was nothing more than that humble but useful bye-product of the farmyard—straw. For some time previously it had been extensively used in France for various articles, but it was left to London to make it quite the rage for the moment, and, curiously enough, a rage which has survived to this day almost every other fashion.

Accident has frequently brought about circumstances of importance, and the application of straw in the manufacture of articles of attire, though perhaps originally a matter of necessity, was the means of introducing a very curious and beautiful production, which, starting modestly at first at Dunstable, eventually reached the Metropolis and assumed huge proportions. The extraordinary hold this new industry obtained in England in a comparatively short time, was such that it was gravely stated by a prominent writer that this apparently trifling article was as much use to the nation as at least one of its most glorious campaigns.

Ornamented with straw

Everything was ornamented with straw at this time, from hats to shoe-buckles. The goddess Demeter seemed to be the favorite idol for the moment of the fashionable world. Ladies of fashion even went so far as to wear straw coats, which were named “Paillasse” and were originally manufactured in France. In fact, it would be difficult to enumerate a tithe of the uses to which straw was put, such was its vogue for a short time. When the first rage for the tegument subsided, it developed into an ordinary manufacture of utilitarian rather than fashionable importance.

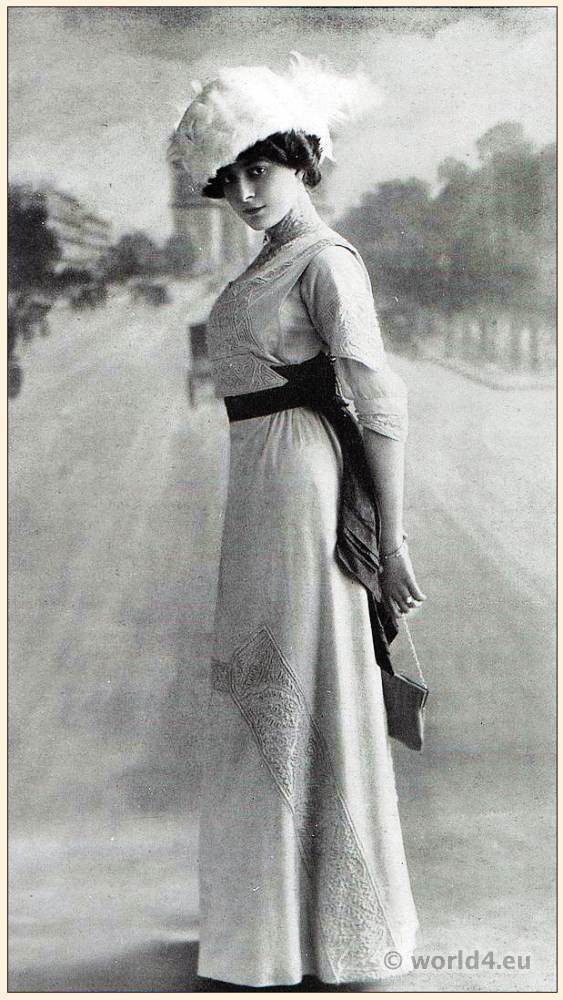

Source: Dame fashion: Paris – London, 1786-1912 by Julius Mendes Price. London: S. Low, Marston 1913.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.