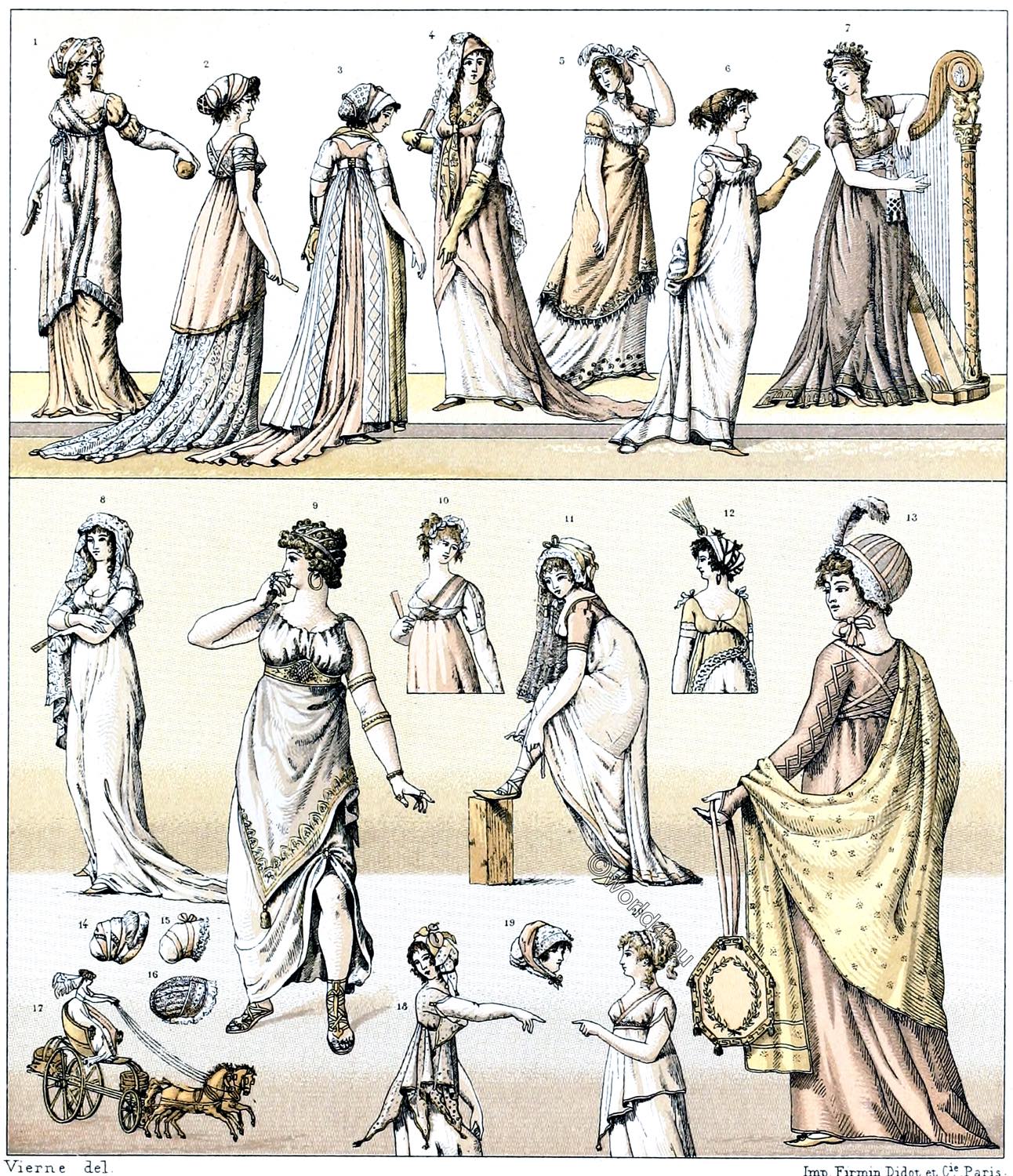

Fashion of classicism in France at the end of the 18th century.

FRANCE. XVIII. CENTURY.

MODES OF THE DIRECTORATE AND CONSULATE (1795-1804).

THE GRAECOMANIA.

The Directory (French: Le Directoire; 26 October 1795 – 24 December 1799) was the last form of government of the French Revolution and belonging to classicism.

After the stormy years of the revolution were over and with it the “time of the Great Terror” (1793), the hard-fought Republic of France had a largely democratic form of government, headed by the Directory – with which the era of the Directoire began.

The search for new traditions and models of democratic culture went back to the time of antiquity. At that time, it was considered to be particularly pure, free and just. Art, architecture and fashion were now influenced by Greco-Roman styles. Incroyables et merveilleuses were a fashionable escapade of the time.

Women’s fashion changed fundamentally, ignoring the previous patterns and now relying on the soft clothes of antiquity. In accordance with this idea, women’s fashion was initially freed from all constraints: no corset, hoop skirt, wig or bonnet. Instead, the fashion à la grecque was simple, sleeveless and partly transparent robes made of white muslin, shoes laced with ribbons around the calves and loosely pinned up hair. The ideal was the classicistic-romantic Graecomania, an obsession with Ancient Greece and Greeks.

Directory (1795-1799).

- No. 9. “A heroine of today.” Antique tunic. with embroidered border and tassels at the ends; agraffes on the shoulders; high bosom belt. The skirt is taken up at the front and fastened by an agraffe above the knee of the tricot-clad leg. Cothurne. Toe and finger rings. Bracelets, elastic bands with pearls. Silk hairnet, covering the hair arranged en frisons d’ebène. Large earrings.

- No. 11 ” Fashions and Customs of the Day”. The illustration, after an engraving entitled “le Prétexte”, shows a fashion lady attaching the ribbons of her shoe. Her curly hair is covered with a lace bonnet, in the bows of which a long black tulle veil is attached. Short tunic with wide cut bodice; transparent skirt with half-tow. covering the tunic from the waist.

- No. 13 “The jealous Aminta, in a hat-like bonnet, with cross bindings over the plain robe, embroidered Shawl, Ridicule, in the Garden of Idalia”. Hair curled deep into the forehead; robe with half-tow, garnished with nakara bows; tight sleeves up to half of the hand; pointed shoes.

- CONSULATE (1799-1804).

- Napoleon Bonaparte overthrew the Board of Directors on 18th Brumaire VIII (9th November 1799) and the following day he was elected First Consul; the two members of the Board of Directors, Ducos and Sieyès, became the other two co-consuls of the three-member consulate.

On 24 December 1799, the Consulate Constitution came into force. This date is considered the end of the French Revolution and the beginning of the Consulate.

1800.

- No. 3. street costume. Capotte of antique shape, reminiscent of the ancient Greek sphendone and the kekryphalos. (Cf. nos. 1 and 2.) Robe with half train. Covered by a tunic attached to the belt with a metal buckle; the hem of this tunic, open at the back, is embroidered with diamonds. Very short sleeveless bodice. Fichu arranged as sash.

- No. 4. Street costume. Velvet hat with lace veil; tunic with train, cut out in front. Long gloves; shawl as neckerchief, pulled through a ring at the front.

- No. 5. Ball gown. Capotte with ostrich feather; tunic with embroidered hem, knotted underneath the bodice; robe with train and Greek hem; bare arms.

- No. 6. house suit. Greek hairnet; long robe with round slits closed by cameos; gloves going over the elbows.

- No. 7. Evening gown. Hair with wide ribbon bow, the knot held by a needle; multi-row pearl necklace; tunic of black crepe, deeply cut. Short sleeves, independent of the bodice; white muslin belt, knotted at the side.

- No. 12. Street costume. Silk capotte, the folds of which are covered by intertwined strands of hair; plume in golden crescent. Low-cut tunic with a triangular tip, folded back at the left side. Gloves of the same colour as the skirt. Large earrings.

- No. 18. Volubilis. Headscarf woven in marble, golden tassels at the ends; winches on the surface of this headdress. Tunic, similar to the Greek chlaene (chiton), with tassels at the ends; one side of the bodice turned down and also decorated with a small tassel. Gloves of the same colour as the robe.

- No. 20. house clothes. Chlaene (chiton), crossed over the chest; white skirt.

1801.

- No. 1. Headscarf like a capotte, held by a silk ribbon; muslin tunic with blue hem; pink skirt with puffed sleeves; long white gloves.

- No. 2. Street toilet. Muslin headscarf; the chignon in a net; lace robe with long train; underarm bands; bracelets.

- No. 8. Costume à la Vestale. Light wide head veil; simple tunic with train.

- No. 10. Evening dress. A wreath in the hair; white canezou, laced on the chest and arm, with blue trimming. Under the bodice a wide underarm band, which connects to the skirt of the same colour.

- Nos. 14, 15, 16 and 19. Bonnet-like headgear; Paris and London.

- No. 17. Phaeton with two horses, steered by a lady. From 1786 on it was fashionable to drive the ladies, alone or accompanied by a jockey.

The imitation of the Greco-Roman costume inaugurated by the painter David during the reign of terror developed more and more under the directorate. The Merveilleuses dressed in the style of ancient statues à la Flore and à la Diane; they wore tunics à la Cérès and à la Minerve, veils à la Vestale, etc. The milliners were assisted in their work by painters and sculptors: Nancy for the Greek, Raimbaut for the Roman costume.

Most of the fashion fabrics, muslin, linon and battist, were of English manufacture and came from the auctions of the prises (Spoils of a privateer trip) made during the naval wars in Brest and Lorient.

The preference for the nude, encouraged by the ancient costume, was counteracted by Anglomania, to which one owed the Shawls, the straw hat and the turban. Coiffure à la Titus also triumphed over long hair towards the end of the Consulate. Towards the end of the 18th century, Jean-Baptiste Pujoulx (journalist and playwright), as he reports in Paris à la fin du dix-huitième siècle, met in a Parisian salon simultaneously three women dressed at a masked ball à la qrecque, à la turque and à l’anglaise.

No. 9 after an engraving: “Les Heroines d’aujourd’hui,” Deret del. and Blondeau sculp.

No. 11 from a series of engravings: “Modes et manieres du jour,” without inscription.

No. 13 after a coloured engraving, as bought from Basset at 670 rue Jacques.

The other figures from the Journal des modes, de la Mesangère, volumes 1800 and 1801.

Cf. de Goncourt, La Société française pendant le Directoire. Quicherat, Histoire du costume en France. – Paul Lacroix, Directoire, Consulat et Empire.

Source: History of the costume in chronological development by Albert Charles Auguste Racinet. Edited by Adolf Rosenberg. Berlin 1888.