GREECE. WAR COSTUMES AND WEAPONS.

The Greek military of antiquity. Spartans, Hoplites, Peltasts.

Before the contact with the Romans, there were no general military regulations for the armament and clothing of warriors among the Greeks. Only the troop bodies of the individual states had certain common insignia, which were determined either by the leaders or by the magistrates. But there is very little information about this. For example, we know that the lacedemonic warriors (Lacedaimonians, Spartans) wore reddish-purple skirts so that the blood flowing from their wounds could not be seen. It is also known that the lacedemonic helmet, which originally consisted only of an egg-shaped felt cap like the cap of the Dioscuri and Ulysses, was later redesigned by public decree because it did not offer sufficient protection against the arrows. Although the Macedonians were heavily armed, they did not give up the helmet of leather.

In order to distinguish themselves from each other, the soldiers put the coat of arms of their cities on the shields. The Athenians wore an owl on their shields, the Mycenaeans a lion, the Argyrians a wolf (Argos), the Macedonians and Thessalians a horse, the Sicilians the triskele, a figure made up of three legs that symbolized the three promontories of the island, the Corinthians a winged Pegasus.

All Spartan shields were marked at the top with a lambda (d) (abbreviation for the Lakedaimonians, the historical name of the Spartan state) the first letter of the name of the city Λακεδαιμόνιο (Sparta), and at the bottom with a kappa (K), the second consonant of the same word.

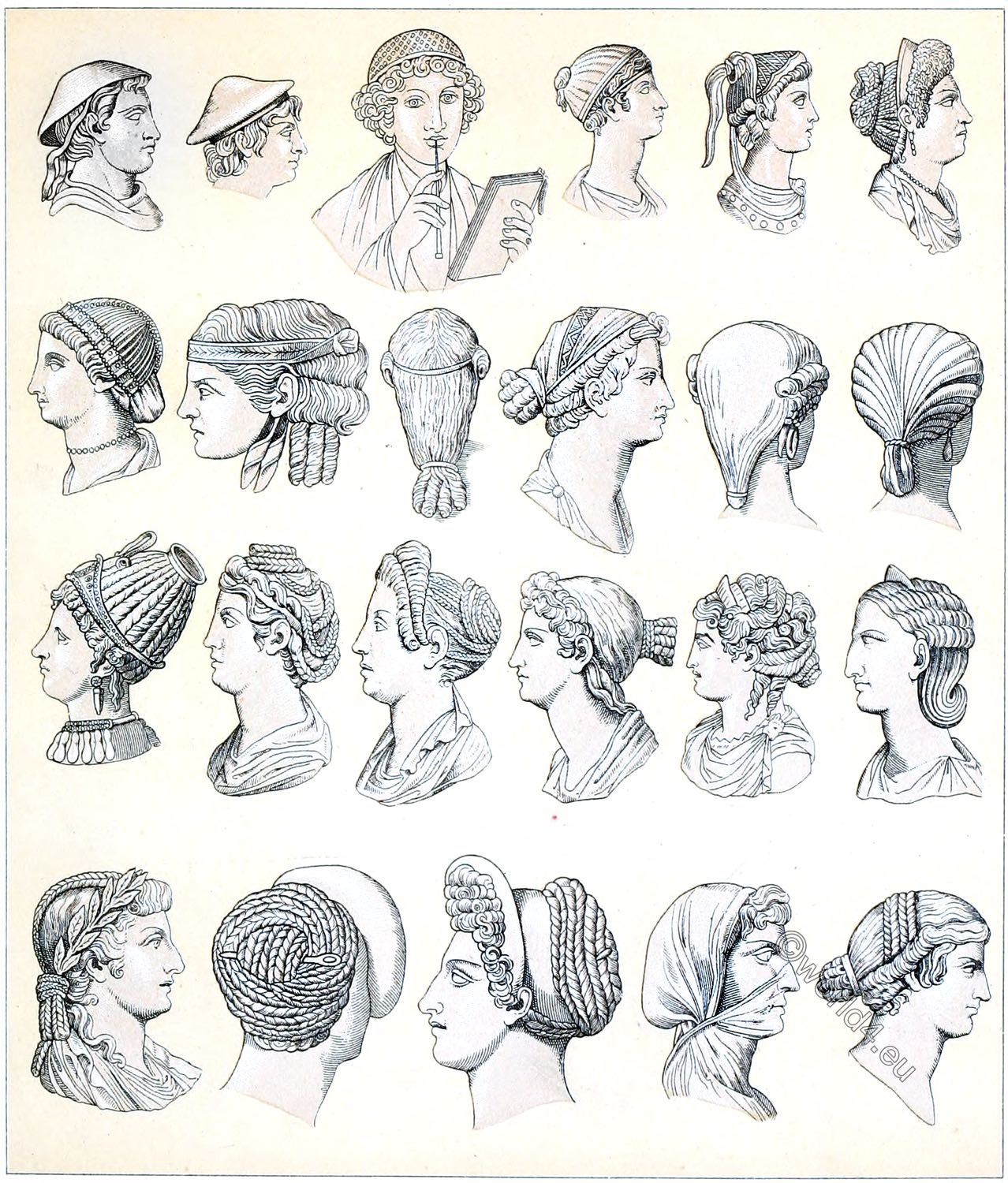

The first initial letter of the city the soldier fought for was usually on his shield, whether or not it also had an emblem. The leaders armed and wore it as they wished. Xenophon wore an Argivian shield, an Athenian armour and a boeotic helmet. The helmets of the leaders were covered with hair bushes. Agamemnon had four tubes on the comb of his own to hold the flowing hair. The helmets of the common soldiers had neither comb nor hair bushes, but a point or a button, or were also kept quite smooth.

Defensive weapons were the helmet, the armour, the belt, the suspension harness, the leg splints, the knee and heel protection, the latter common for riders, the arm splints, the shield and, if one did not have the latter at hand, also the Chlamys (short riding and travelling coat), which one wrapped around the left arm to absorb the blows of the enemy.

Attacking weapons were the club, the lance, the long or short sword, the dagger, the knife, the so-called harpe, a kind of sword with a sickle-shaped edge at the tip (used by Perseus in the killing of Medusa), the axe, the hammer, single or double, the bow, the throwing spear and the sling with lead balls. In the heat of the battle, the heroes, as one sometimes reads in Homer, also reached for the stones that were lying around on the battlefield. Finally, one can also pay the shield to the attacking weapons, since occasionally one struck the enemy with the raised navel of the same or tried to push him back with it.

The helmets were of metal or leather. Since instead of helmets in the oldest times the heads of animals were worn together with the whole fur serving as a coat, the artificial helmet initially kept the shape of the natural one and was therefore equipped with ear flaps. The metal helmets were lined inside with leather or with padded canvas, which formed a hem, or one wore a felt cap under the helmets. The soldiers decorated the leather of the helmets and the leather covering of the shields with paintings, as you can see at no. 10, 12, 13 and 15. The boeotic helmet with nose protection and large, firm cheeks and neck guard (no. 18) is worn most often by warriors on Greek vases. The differences of the helmet decoration gave it a manifold appearance. Waving hair tails were formerly common as feather bushes. With the progress of the industry, the individual parts of the helmet, especially the visor, were also made movable. The helmet was held by a strap under the chin.

The armour was made of metal or leather or of spun flax with multiple linings. Although the latter material seemed to be not very resistant, the Athenians took it up again after having worn iron or bronze armour for a while. The Macedonians still wore cloth armour at the time of Alexander the Great. Fig. 5 shows a hero with such armour, which is still covered with metal plates. The shoulder blades, composed of jointed plates, are fastened with cords which are pulled over the chest and knotted together underneath.

At the lower end of the armour, leather strips were attached to protect the belly, often in double rows one above the other, forming a kind of apron. The metal armour joined the human body in its forms. If it was a whole, i.e. intended to protect the chest and back, the two armour pieces were strapped together at the sides.

Or the armour was held together by hinges on one side and straps on the other. The armour worn over the tunic or chiton was often decorated with engravings. Those who were not dressed in a tunic wore a short, apron-like skirt under the armour, which was tied around the hips. Homer talks about this skirt that our Fig. 18 seems to be wearing.

As you can see at No. 2, under the leather frenzy you also wore a finely worked tunic made of striped stitches. A belt holds the tank and tunic together. The pendant hung down from the right shoulder to the left side, where the sword was carried almost horizontally. If the leg splints, which also followed the shape of the legs exactly, covered the entire lower leg, they did not need to be attached (No. 18). However, if they only protected the front side of the leg, they were strapped together at the back under the knee and under the calf with straps.

The shield was the main defensive weapon. It was usually round and curved inward. The handle for the hand was located inside at the top edge of the bows for the arm in the middle. A sling was used to carry it on the back while marching, hung around the neck. Originally the shield was woven from willow branches, later it was assembled from small boards of fig, willow or beech wood. Then shields were made from ox hides by placing several of these hides on top of each other and holding them together with nails or a metal edge. The shield of the Ajax consisted of nine ox skins laid on top of each other.

Here and there metal plates were put on and in the middle a curved piece of metal, which the Romans called umbo, navel. It was used to catch sword strokes and to strike the opponent. In further development of the shield, certain badges, mostly animals and heads of bronze, were placed in the middle, namely on the shields of the leaders. When the outer side of the shield was completely covered with metal, sometimes the whole metal surface was decorated with artistic reliefs. Famous are the descriptions of the shields of Achilles, Hercules and Aeneas in Homer, Hesiod and Virgil. A popular shield sign was the head of Medusa, which Athena first included in her shield and to which defensive and frightening power was attributed.

The place of the bronze ornaments was also represented by paintings. Apart from the round and oval shield, the Greeks also used the crescent-shaped shield, the pelt, which seems to be of Asian origin, since it is worn by the Amazons. With the Greeks they wore the peltasts, a light infantry. In contrast to the Peltasten is the Hoplit, the heavily armed man who formed the phalanx and had to carry a 12 – 15 feet long lance in addition to the shield and the sword. No. 4 is an archer who is even more lightly armed than the Peltast. The archers were mostly used as skirmishers.

No. 2 represents a lightly armed horseman. He rides without saddle and stirrups and the horse has no horseshoes. No. 3 represents Orestes. Remarkable are the high, pointed cap and the leg dresses reaching to the knees, which remind of the costume of the Scythians and Thracians. In heroic times, weapons were made of copper, tin and bronze.

No. 1. helmet with neck and nose protection, which covers almost the whole face.

No. 6 and 17. helmet with movable ear protection, which is folded up.

No. 7. Phrygian helmet.

No. 9 and 11. Sword with its sheath. The scabbards were made of wood or ivory.

No. 16. Hunter with chlamys, cap and throwing spear.

(According to Willemin: Costumes des peuples de l’antiquité)

Source: History of the costume in chronological development by Auguste Racinet. Edited by Adolf Rosenberg. Berlin 1888.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.