IONA, THE SACRED ISLE

“THAT MAN IS LITTLE TO BE ENVIED WHOSE PATRIOTISM WOULD NOT GAIN FORCE UPON THE PLAIN OF MARATHON, OR WHOSE PIETY WOULD NOT GROW WARMER AMONG THE RUINS OF IONA.”

DR. SAMUEL JOHNSON.

CLOSE proximity to the western coast of Scotland lie a number of islands which are known collectively as the Hebrides or Western Islands. One of the largest of them is Mull, at the mouth of the Firth of Lorne; and off the outer coast of Mull lie two small islands of special interest — Staffa and Iona. The neighboring shores of Mull are rocky and desolate, and to the westward one can see little if anything except the broad sweep of the Atlantic Ocean; so these small islands seem remote and lonely, but they are, in fact, quite accessible, being made the objective points of daily excursions from Oban.

The course is taken around the island of Mull in opposite directions on alternate days. If one chooses to take first the inside passage through the Kyles of Mull, he enjoys a couple of hours of picturesque scenery—particularly on the right, where the Morven hills of Argyllshire present good examples of that peculiar style of beauty so often seen in the heather-covered hills of Scotland.

Near the entrance of the Sound are the ruins of Duart Castle, the ancient stronghold of the MacLeans. A little farther, on the Morven shore, is the site of Ardtornish Castle, where Edith, “Fair Maid of Lorne,” came to wed Ronald, Lord of the Isles. Other points of similar interest are revealed as the steamer passes up the Sound.

In fact, this excursion, like so many others in Scotland, derives additional interest from the legendary history of the neighbouring country. It is a land of legends; and the borderline between these legends and the authentic history of the nation is often so obscure as to be undistinguishable. However, this legendary feature cannot be eliminated without causing the loss of one of the greatest charms of Scotland.

After rounding the northern shore of Mull, the course is taken to the southward towards Staffa, where an hour is allowed for visiting Fingal’s Cave, that singular formation whose aspect is so well known. The landing is effected in life-boats, and the place of disembarkation is changed from day to day, according to the direction of the wind and the condition of the sea. The approach to the cave is by a pathway over rocks which are often so slippery as to interfere considerably with a proper appreciation of the phenomenal character of the island. A sudden turn reveals the mouth of the cavern; and when the sea is smooth, those who are venture-some may penetrate to its farthest recesses. The tall basaltic columns which line the sides, and the vaulted roof which they seem to support, combine to give an ecclesiastical aspect to this wonder of nature. It has been well described as

… that wondrous dome,

Where, as to shame the temples decked

By skill of earthly architect,

Nature herself, it seemed, would raise

A Minster to her Maker’s praise.

Staffa presents no other feature of special interest, so the voyage is soon resumed, and after a short sail the steamer drops anchor at Iona, where the field of interest is much broader. Many centuries of civil and ecclesiastical history furnish material for research, and at the focal point, towards which the lines of inquiry all converge, stands St. Columba.

Iona belongs to the Duke of Argyll. It is of small size, about three miles long by about one mile wide; and the part which the excursionists see is only that which is covered by the little village extending along the shore by the landing.

The superficial observer finds merely an island without natural beauty, in fact of rather barren appearance, containing a cluster of little houses, a few ruins, and an ancient-looking church, partly restored; but the island bears a different aspect when we realise that it was one of the most influential centres for the civilisation and conversion of Scotland — a spot considered so sacred that kings were taken there for burial, and so important as to have been a bone of contention between Scots, Danes, and Norsemen. It has been referred to as “for two centuries the nursery of bishops, the centre of education, the asylum of religious knowledge, the point of union among the British Isles, the capital and necropolis of the Celtic race.”

SPECIAL interest in this little island is created by its close connection with St. Columba, that wonderful man whose life-work is deeply engraved upon the history of Great Britain.

Columba was an Irish monk of royal descent. Tradition states that he became involved in a controversy which ended in a sanguinary war; and that he was ordered to leave Ireland and to remain away until he had converted to Christianity as many persons as had fallen dead by the hands of himself and his followers. Taking twelve companions, he left the home that was dear to him, and headed for the coast of what we now call Scotland. Tradition says further that he stopped first at the Mull of Kintyre, and later at the island of Oronsay; but, finding that even at this place he could still see the shores of Ireland, he pressed on, and landed at Iona, where he decided to remain. A little bay on the southern shore is pointed out as his place of landing, and just above it is a cairn which marks the spot, where, finding that his native land had passed from sight, he was ready to take up his new work, an exile but an enthusiast. The incident occurred in the year A. D. 563, thirty-four years before St. Augustine landed in Great Britain. It is generally believed that Iona had been, and perhaps was then, inhabited by Druids. The ancient Gaelic name of the island was unis nan Druineach, the Isle of the Druids.

Columba cannot be regarded as the first Christian missionary who came to this region, as there are indications of an earlier migration from Ireland to these shores, and a possible occupation of Iona by Celtic Christians. In any case, Columba appears to have obtained peaceful possession, which was confirmed later by Conal, the King of the Northern Scots, to whom the island belonged. Columba and his followers began their work promptly; and their activity and vigor soon brought wonderful results.

From this centre they carried on a beneficent work, which was in time widely extended all over Northern Britain. Many churches and monasteries were founded; and Iona came to be a centre of great influence. Its fame as a holy place spread far and wide; and when, after the death of Conal, his cousin Adian became King of the Scots, the new monarch came to Iona to be crowned by St. Columba. The stone on which he sat, the “stone of destiny,” was thereafter used at the coronation ceremony of the Kings of Scotland. It was later taken to Dunstaffnage and to Scone, and in 1296 it was moved to London. It may still be seen in Westminster Abbey, fastened under the seat of the chair in which the monarchs of Great Britain are crowned.

An interesting reference to this incident is found in a little book, long since out of print, which was written by the Duke of Argyll about forty years ago, under the title “Iona.”

The author writes as follows: “Hither came holy men from Erin to take counsel with the Saint on the troubles of clans and monasteries which were still dear to him. Hither came, also, bad men, red-handed from blood and sacrilege, to make confession and do penance at Columba’s feet. Hither, too, came chieftains to be blessed, and even kings to be ordained—for it is curious that on this lonely spot, so far from the ancient centres of Christendom, took place the first recorded case of a temporal sovereign seeking from a minister of the Church what appears to have been very like formal consecration.”

It affords a good illustration of the far-reaching interest which attaches to this little island.

There is also a tradition that this stone is identical with the stone of Luz, on which Jacob rested his weary head; but one may be pardoned for feeling a little skeptical when tradition oversteps so far the bounds of probability.

In time, the island came to be known as Icolmkill, “the island of Columba of the Church,” or “the island of Columba of the burial-place” — both translations being given as the English equivalent of the Gaelic title.

Columba died in 597. It is stated that, when he saw death approaching he spoke prophetically of the future of Iona, assuring his associates that their insignificant little island would be one of the honorable places of the earth; and that the kings and people of Scotland and of other nations would reverence the spot. This prophecy has been well fulfilled. In addition to the monastical work carried on by the successors of Columba, a special interest in Iona was created by its use as a burial-place for dignitaries of Church and State. Here for centuries were brought the bodies of kings, warriors, chieftains, and ecclesiastical rulers, that they might rest in this sacred place.

One who visited Iona in the sixteenth century gives a description of a burialplace in which there stood three tombs of stone, built like chapels, and each bearing an inscription. On one were the words Tumulus Regum Scotia, and in this were buried forty-eight Scottish kings, including Duncan and Macbeth.

On another tomb were the words Tumulus Regum Hiberniae, and this contained the bodies of four Irish kings. The third tomb was marked Tumulus Regum Norwegia, and here lay buried sundry Norwegian rulers, who, if not literally Kings of Norway, were at least Kings of Norwegians. The Hebrides were more or less subject to Norway for about four centuries, and their rulers bore the title “Kings of the Isles.” Within the burial place lay also the bodies of most of the Lords of the Isles, those rulers who held sway, with more or less independence, in the centuries following the Norwegian occupation. The tombs referred to have disappeared, but the burial-place — in part, at least — is still to be seen. Its ancient name was Reilig Orain, the burial-place of Orain or Oran. Considerable doubt exists about the identity of the Saint after whom it was named. He is reported to have been Columba’s brother, but the oldest existing list of Columba’s companions does not include his name. Some think the name is that of an Irish saint who died before Columba came to Iona. Numerous gravestones are found, most of them lying flat on the ground. Several of the most interesting ones have been gathered together and laid side by side, and surrounded by iron railings for protection from hunters of relics.

The gravestones are worthy of much more careful examination than is possible in the hasty visit of the excursion parties. They bear carvings of a curious character, comprising a wide variety of designs. There are representations of animals, and of galleys, swords, crosses, geometrical designs, and various symbols and devices of a mysterious character. Some of the stones are covered with elaborate traceries. Many bear figures of the dead cut in low relief; and others have similar figures in the shape of effigies raised up on the face of the stones. In many cases the stones can be identified; and these are mostly commemorative of chiefs of Scottish clans who died between the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries inclusive. The older monuments have disappeared. One stone in the enclosure is said to cover the body of a King of France.

The burial-ground was, in the ancient times, approached by a road which led from a bay where the funeral parties landed. This road was known as the Street of the Dead, and although it is now obliterated, there are landmarks to indicate its general direction through a part of the village. It takes but little imagination to picture the sad processions of men of high degree which passed along that path in the days when Iona was looked upon as holy ground.

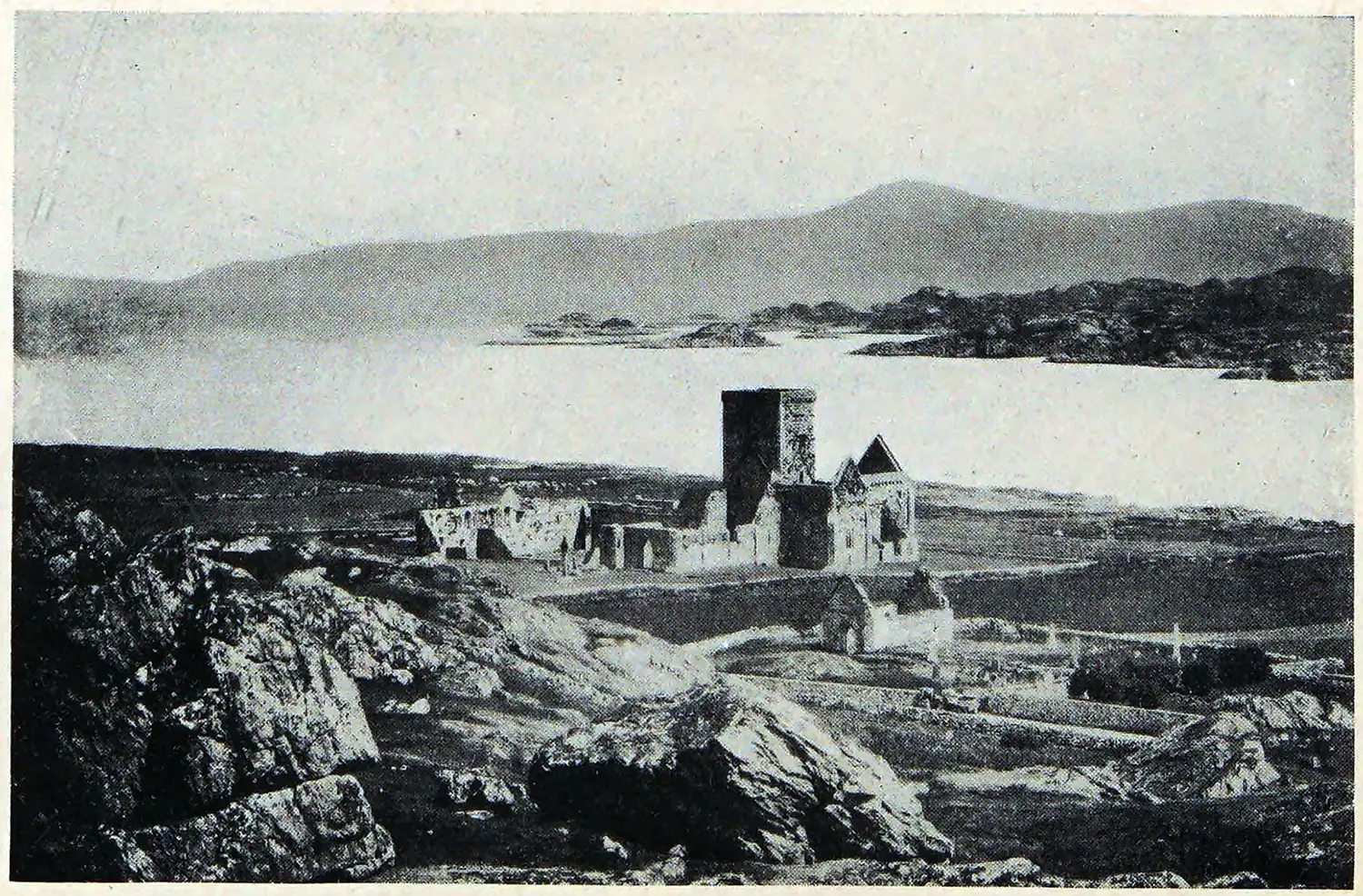

There are other points of interest for the antiquarian, besides the graveyard mentioned above. The ruins of a nunnery, which was founded about the end of the twelfth century, are shown as one passes from the landing to the graveyard. St. Oran’s chapel is a ruined building, about thirty feet long, concerning which little appears to be known. It stands within the enclosure of Reilig Orain, and was probably built about the eleventh century. Across the burial-yard and near the shore of Iona Sound, stands the Cathedral. It is a stone building of about the thirteenth century, measuring about 150 feet in length, and having a square central tower. The style of the building is simple, but impressive. The choir has undergone a process of restoration in recent years. The nave is in ruins. Adjacent to the Cathedral are the ruins of the monastery buildings.

Abbey on Iona. Photo by Henry Bloomfield

Near the Cathedral door stands St. Martin’s Cross, a relic of considerable interest to those who are versed in Celtic antiquities. It is about fourteen feet high, of a gray stone, and similar in general appearance to others still to be found in Great Britain and Ireland. It is quite different in style from the Latin cross; the arms are short, and they are connected with the head of the cross by an attached circle. The cross was erected to the memory of St. Martin of Tours, and it is believed to date from the twelfth century, or earlier. Another cross, MacLean’s, stands nearer the village, but is considered to be of a much later date.

It is to be noted that the only relics of antiquity now visible are of a much later age than that of Columba. Various localities are pointed out as connected with the incidents of his life, and apparently with a considerable degree of accuracy; but a detailed consideration of them would only be of interest to the compilers of guide-books or to those who desire to make a complete study of the Saint’s life and times.

It would be difficult, if not impossible, to give in brief compass a satisfactory account of the great work which was either carried on personally by Columba and his associates, or may be attributed to their influence and inspiration in the lives of those who followed them. Picts, Scots, and Britons came under the spell of those earnest men, who did not con- fine themselves to the mainland, but visited also the distant Hebridean islands, and even went, according to report, as far as Iceland.

After Columba’s death the influence of this old Celtic church became even more widely extended. Oswald, King of Northumbria, asked for a missionary from Iona to labor among his people, and Aidan was sent. He established himself upon the island of Lindisfarne, off the Northumbrian coast; and so by degrees the influences which originated at Iona spread out over the southern half of Great Britain.

During the two centuries after Columba’s death, the monastic work of Iona passed through various vicissitudes, mainly theological. In the following two centuries there were stormy times from other causes, as the Island was frequently ravaged by the Danes and the Norsemen. In 1074 the Western Islands came under the rule of Malcolm Canmore, a Scottish king, whose queen, Margaret, is said to have restored the monastery at Iona from the demoralisation resulting from these times of war. For several centuries after this time, comparatively little is known of the island’s history.

FULL consideration of Iona’s place in literature would require more extended treatment than is appropriate to this sketch; but it is desirable to note two interesting features of her literary history—one in the remote past, and one in our own times.

It is a remarkable fact that we have a biography of the Saint of Iona written by one who was born only a few years after Columba’s death, so that the book has almost the value of a contemporary work. Adamnan’s “Life of St. Columba” was no doubt a book of great interest to those who lived in the seventh century, but it does not appeal to the literary tastes of our own times.

The book is divided into three parts. Generally speaking, the first part treats of the Saint’s prophetic revelations; the second part tells of his miraculous powers; and the third part relates the angelic visitations which were granted to him, and also describes his last days upon earth. The foregoing divisions are not, however, strictly maintained, and it is unnecessary to discuss them separately and in detail.

If we were prepared to believe one half of the incidents related, we should need no further proof that Columba was one of the most remarkable men the world ever saw. It is stated that he cured men of diseases, drove away demons, controlled wild beasts, quieted stormy waves, turned water into wine for use in the Mass, mended broken bones, caused grain to ripen early although sowed late, and lastly, that he even raised the dead. It is stated that on one occasion he received requests for favourable winds from two men who wished to sail at the same time in opposite directions, and even this was accomplished by his power. Adamnan evidently thinks it necessary to fortify this last incident against any possible doubts, so he takes pains to explain that the power of Columba’s prayers was great, and reminds the reader that “all things are possible to him that believeth.”

Many incidents are given of Columba’s prophetical powers, not only in foretelling future events, but also in apparently seeing events occurring at the time in places beyond the range of human vision. Here, although still skeptical as to details, we are forced to acknowledge the possibility that there may be some truth in the incidents related. The gift of “second sight” has been for many centuries more or less common in Scotland. Some have considered it merely the product of an overwrought imagination; but others have claimed for it some degree of reality. All that need be said here is that we need not consider these manifestations of Columba’s powers as necessarily based entirely on fable.

The most interesting part of the book is found in its closing pages, where a detailed account is given of Columba’s last days upon earth. The wonderful stories mentioned above, which have taxed our credulity, are soon forgotten as we read the simple and yet graphic narrative of the premonition of death, the long farewell, and the sorrowful assembly of the monks in the church when the aged man passed away at midnight on the altar steps. In fact, leaving aside the references to supposed prophetical and miraculous powers, there is throughout the book a singular attraction in the story of the simple life of benevolence which was lived by these monks of Iona.

It has been said that Adamnan thought in Gaelic and wrote in Latin. While, therefore, the Latin form disappears in the translation, it is not strange that we should, nevertheless, still recognise in this work the highly developed imagination and the love of the supernatural which are so closely associated with the Gaelic nature. These characteristics, it may be noted, have not passed away from the modern representatives of that ancient race; and no doubt their preservation is to some extent due to the continued use of the Gaelic as a living language in the Hebrides and the Scottish Highlands.

THE same spirit of fable and legend which permeates Adamnan’s stories of the distant past, is still hovering about this little island in our own times; and it is especially manifested in the writings of that one recent author who, more than any other, speaks for lona in modern romantic literature, Fiona Macleod. The interest which Miss Macleod’s works themselves create is much increased by the facts about her which have recently been revealed. She was understood to be a lady of Hebridean or Highland family, whose identity, for reasons of her own, it was necessary to conceal.

It follows, therefore, that little could be ascertained in regard to her.

The late William Sharp claimed to know Miss Macleod; various statements were attributed to him with reference to her; and it is even said that he presented to some of his friends a lady bearing that name. Since his death it has been authoritatively announced that the name “Fiona Macleod” was a pseudonym, and that Mr. Sharp was himself the real author. Even with this knowledge, however, it will never be possible to dissociate these writings from the name over which they appeared. Miss Macleod may not have existed.in the flesh, but she is, nevertheless, in the literary world a distinct and living personality, with strongly marked characteristics. The hand that wrote was the hand of William Sharp, but it held a woman’s pen.

An enthusiastic interest in the Gaelic people, their legends, and their folk-lore, is manifested in this writer’s work. Its field covers all the Hebridean islands, but the central point is Iona. It is not, however, the quantity of the material referring to this island, but rather its quality, which attracts our interest.

Two articles about Iona over the signature of “Fiona Macleod” appeared in the Fortnightly Review during the year 1900; they were afterwards revised and enlarged, and published in book form, under the appropriate title, “The Isle of Dreams.” The following extract from that book is not only characteristic in style, but also singularly expressive of the author’s point of view:

“A few places in the world are to be held holy, because of the love which consecrates them and the faith which enshrines them. Their names are themselves talismans of spiritual beauty — of these is Iona.

“But to write of Iona, there are many ways of approach. No place that has a spiritual history can, to those who know nothing of it, be revealed by facts and descriptions. … I have nothing to say here of Iona’s acreage, or fisheries, or pastures; nothing of how the islanders live. These things are the accidental. There is small difference in simple life anywhere. Moreover, there are many to tell all that need be known.

“There is one Iona, a little island of the West. It is but a small isle, fashioned of a little sand, a few grasses, salt with the spray of an ever-restless wave, a few rocks that wave in heather, and upon whose brows the sea-wind weaves the yellow lichen. But in this little island a lamp was lit whose flame lighted pagan Europe, from the Saxon in his fens to the swarthy folk who came by Greek waters to trade the Orient. Here Learning and Faith had their tranquil home, when the shadow of the sword lay upon all lands, from Syracuse by the Tyrrhene Sea to the rainy isles of Orca. From age to age, lowly hearts have never ceased to ease their burthen here.

To tell the story of Iona would be to go back to God, and to end in God. There is another Iona of which I would speak. I do not say that it lies open to all. It is as we come that we find. If we come bringing nothing with us, we go away ill-content, having seen and heard nothing of what we had vaguely expected to see or hear. It is another Iona than the Iona of sacred memories and prophecies —Iona the metropolis of dreams. None can understand it who does not see it through its pagan light, its Christian light, its singular blending of paganism, and romance, and spiritual beauty.”

The reader quickly finds himself in an atmosphere of legends, dreams, and imaginations. Some of these are of a religious nature, such as the belief current in some quarters that Christ will appear again upon Iona; and a legend that Mary Magdalen was buried in a cave on the island; and a strange and indefinite expectation that there will be on Iona a further manifestation of the work of redemption through the advent of a Divine Woman.

Other legends are of a secular character, in most cases touching the underworld of mystery and magic. We are told of the Sidhe or People of the Hills, who, though found in some of the lonely isles, have their kingdom in the Far North. It is related that one of Columba’s monks sailed towards their country; and he sailed and sailed for nine years, and then lived with the Sidhe for three hundred years, and finally came back to Iona. He related his adventures to the monks then on the island, but when he began to tell of the lovely creatures he had seen in that far distant land, he was promptly buried alive!

Shonny, a sea god, is mentioned— evil in his ways, and greatly feared. There is also another sea god, Menaun by name, who sometimes lives in the sea, fashioned in a mysterious shape, and sometimes goes ashore in the guise of a human being. We read also the legend of Black Angus, who was turned into a seal; and we are told of a monk who preached the Word to the seals along the shore. There are also tales of “second sight,” and various stories of life on Iona and the neighbouring isles, — all having a local color which invests them with a great charm.

In another book the author tells a legend of St. Brighid or St. Bride, who has always been dear to the Gaelic heart under her name of “Muime Chriosd” — the Foster-Mother of Christ. Briefly, the story relates how Brighid and her father were shipwrecked on the shore of Jona. The little girl was welcomed by the Druids, who recognised in her the fulfilment of a prophecy. She grew up beautiful in appearance and in character. One day, at the Fountain of Youth, on Dun-I, *) she saw a vision of a woman of great beauty. Soon afterwards a white dove appeared who led Brighid far away, over distant desert lands, to Bethlehem, where her father was keeping an inn.

*) The hill on Iona.

In the father’s temporary absence from the inn, an elderly man with his wife asked for shelter. The wife addressed Brighid in Gaelic, and Brighid recognised her as the lovely woman who had appeared in the vision on Iona. The pair were lodged in the stable, and there the Babe was born. Brighid nursed the Child while Mary slept. Towards morning Brighid fell into a deep sleep, and when she awoke the travellers were gone. She set out to follow them, and finally caught a sight of the city of Jerusalem; and then suddenly was transported back to Iona and to her old life.

Aside from the anachronism of referring to St. Bride as living at the time of the Christian era, there are other matters which a friendly criticism must overlook. We cannot think of the Scriptural incident taking place at an inn called “Rest and Be Thankful”; nor does it accord with our ideas to read of collies and pipers, and of people drinking ale and eating oatcakes and scones, in Bethlehem. But these features are only incidentals; the essential part of the beautiful legend remains, and its beauty is enhanced by the graceful way in which it is related.

Another legend of the island tells how Columba conversed one day with Ardan, an ancient Druid, about their respective religions. Ardan stated in the course of conversation that the birds all knew the mystery of the Cross. Columba meditated long over the idea; and the next day, to test the statement, he called to the birds togather at Iona. They came from every quarter, from distant moors and lochs, and mountain sides; and Columba said Mass for them as they sat around him.

Among the various tales of Iona— ancient and modern, sacred and secular — found in Fiona Macleod’s works, there is one which is worthy of special mention, The Sin Eater.

Neil Ross, after a long absence, is returning to Iona, unrecognized through the changes which the lapse of years have wrought. He hopes for a chance to stop on the way and curse to the face his old enemy, Adam Blair. From an aged woman, who finally recognises him, he learns that he is too late, for Adam has just died, and is laid out for the burial. As Neil is in sore need of money, he is persuaded to earn a fee, in accordance with a current superstition, by taking upon himself the sins of the dead man.

This could be done by an entire stranger, who naturally bore no grudge in his heart; and in such case he would be gradually purified of the sins by the air of Heaven. Neil accordingly eats some bread and drinks some water which had been placed on the breast of the corpse, receives his fee, and departs. He had been told that even if the Sin Eater had a grudge, he could, nevertheless, find a way of easing his burden of sins by casting them into the sea.

It appears, however, that the sins could not be thus disposed of if the Sin Eater was concealing a crime; and Neil soon found he could not get rid of the awful burden he had assumed. He crossed over to Iona to live in his old ancestral home, but he found his homecoming was very different from his anticipations. Shunned by the inhabitants, who seemed to suspect some deep mystery, he went deeper and deeper into the horrors of madness; tried again and again to prevail on the waves to take his burden; called himself Judas; and finally was drowned, tied to two pieces of wood fastened together in the shape of a cross.

This brief résumé gives no idea of the graphic style in which the narrative is told. The scene at the death watch, when one old woman tells another that the mice have left the house because the soul of the dead man, loth to leave, is trying to hide in the dark corners and behind the walls; the description of the mysterious rites according to which the Sin Eater performed his task; the account of how the corpse laughed when the mourners saw Neil going away; all these are examples of word-painting which must be read to be appreciated.

It is a pleasure to turn from an awful tale like this to some of the other stories which show the beautiful side of Gaelic folk-lore—such, for instance, as the story of The Anointed Man. Allison Achanna was not understood by his neighbours. He was “fey.” He could always smile, even when surrounded with distress and suffering. Once he explained to a little girl why he was thus. Years before when lying on the ground with his face buried in the heather, two tiny hands had pressed something soft on his eyelids. He had been touched with the Fairy Ointment, and thereafter all the world and all its inhabitants were beautiful, and there was no more sin, nor ugliness, nor distress.

Surely no further examples are necessary to prove how appropriately this little island is called “The Metropolis. of Dreams”; but only the original writings themselves can show the perfection of the local color which adds such a charm to the gifted author’s works.

A phrase, or a brief sentence, alludes to some aspect of nature or some manifestation of its forces, and one immediately recognises the accuracy of the Hebridean picture.

The direct references to Iona are, of course, only incidents in the consideration of the broad field of Gaelic tradition and folk-lore; but it is made clear that there is no other spot in Scottish Gaeldom which can compare with Iona in the absorbing interest which it inspires-—whether viewed from the standpoint of history, of religion, or of romance. In fact, it is the peculiar combination of Christianity, Paganism, History and Romance associated with Iona, which makes this interest so great. The author’s power comes from a deep affection and admiration for the Gael, and a soulful sympathy with all that is sad and mysterious, as well as all that is beautiful, in his nature and in his literature.

LEAVING the island, the homeward course lies first to the southward, among the numerous reefs and rocky islets of Iona Sound; and then, rounding the corner of Mull, the steamer passes from the open sea into the Firth of Lorne, towards Oban. On the left lie the rocky shores of Mull—desolate, and yet picturesque, since the granite rocks are streaked with red, and covered here and there with patches of green moss. There is no sign of life except the great flocks of gulls, and the puffins, cormorants, and other birds which are moved to flight at the approach of the steamer.

The voyage is ended at Oban towards the close of the afternoon; and the picturesque view of the town and its vicinity which is afforded by the approach up the Firth of Lorne is a pleasant incident in this enjoyable and unique excursion.

Yes, the voyage is over, but the memories it arouses will not soon pass away. We have been on the borders of Dreamland, and have learned something of its mysteries. Let us not, however, be so fascinated by our experiences in this respect as to overlook that which is substantial and enduring.

It has been necessary to take a distant view into centuries long past, in order to obtain an adequate impression of the important part which this island has played in the history of Great Britain.

One should not visit Iona with the expectation of seeing beauty of landscape or of architecture; her great claim on the traveler’s attention lies rather in her far-reaching historical interest, and in her sacred associations. When one thinks of the distant centuries during which this little island was like a beacon light standing for Christianity, civilisation, and useful knowledge; when one appreciates the fact that beneath the sod lie the bones of kings, chiefs, abbots, monks, priests, and others who, in their generation, were important factors in the civilisation and the religious and civil government of the country; it is then that one realises Iona is a place of more than ordinary interest. For the early years of the nation’s history it is the Westminster Abbey of Scotland.

Source:

- Iona, the sacred isle; by Robert Jaffray (1854-1926). New York, Priv. Print. [The Gilliss Press] 1907.

- Scotland by Joan Berenice Reynolds. London : A. and C. Black, 1915.

Related

- Canterbury Cathedral. The ecclesiastical metropolis of England.

- Nave of Wells Cathedral. Main work of early English Gothic architecture.

- Ely Cathedral in Cambridgeshire, England.

- Glastonbury Abbey in the county of Somerset, England.

- The market cross at Glastonbury, Somerset.

- The Gloucester Cathedral.

- The cathedral of Notre Dame, Paris.

- Monasteries and Cloisters as Centres of learning and Culture.

- Rouen Cathedral coronation site and burial place of the Norman dukes.

- Figures of Ecclesiastics of the cathedral of Chartres.

- Tintern Abbey. An excellent specimen of pure Gothic architecture.

- The cloisters of Belem. The Mosteiro dos Jerónimos. Lisbon, Portugal.

- The Mosteiro dos Jerónimos, also known as Jerome Monastery, Lisbon.

- Al-Andalus. Interior of the Mosque at Córdoba, Spain.

- Pilgrimages and the sacred hills of Buddhism in China.

- The Laura of Mar Saba near the Dead Sea.

- Convent of Mar Saba. The Holy Laura of Saint Sabbas. Palestine.

- The Franciscan Convent of the Terra Santa, Nazareth.

- Early monastic life and the controversy over icons.

- The daily life of the monk favourable or detrimental to creative work.

- The Holy House of Loreto. The Basilica della Santa Casa.

- The convent of St. Catherine at Mount Sinai, Egypt.