THE EXECUTION OF LORD RUSSELL.

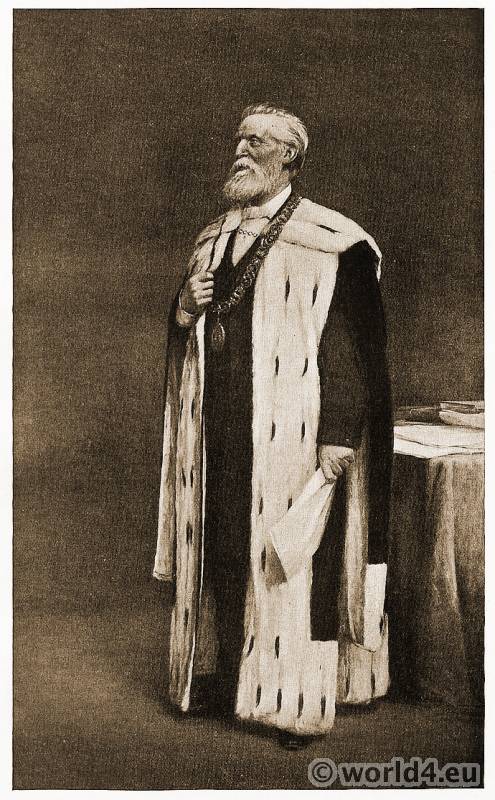

Lord William Russell (1639-1683) was an English politician.

Among the leaders of that party which for a time successfully opposed the attempts of Charles II. and the Duke of York to re-establish arbitrary rule, and to favor the restoration of Romanism in England, one of the most prominent was Lord Russell, usually called Lord William Russell, son of William, Earl of Bedford, and Lady Ann Carr, daughter of Carr, Earl of Somerset.

Lord Russell, Lord Essex, Mr. Hampden, and Algernon Sidney were the principal supporters of the Exclusion Act, by which the Duke of York was not only compelled as a Papist to resign the admiralty, but would have been forbidden to ascend the throne. For a time they succeeded; but there arose a host of false accusers like Titus Oates and Dangerfield. Papist plots and Protestant plots were the subject of continual alarm and excitement, and the reign of persecution again set in. James, Duke of York, was sent to Scotland with plenary powers, which he used in putting Covenanters to the torture. Charles, without formally breaking the laws of the constitution, temporized, as it seemed, to discover how he might himself best profit by either party. Louis of France did his utmost to provoke anarchy by intriguing with all parties at the same time. A reaction came, which was greatly instigated by the violent measures taken against Roman Catholics by the Whig majority in the House of Commons.

The Duke of Monmouth, the illegitimate son of Charles, was one of the exclusionists, but was, it is supposed, too anxious information which tended to the ruin of his friends. Shaftesbury was, if not the most violent, the most determined of the opponents of the claims of the Tories, and he declared that he could raise a force in the city, while Monmouth was to influence a rising in Cheshire and Lancashire, and Trenchard was to stir up the people of Taunton. The king and his counsellors had not been idle. Parliament was dissolved, and a new parliament in the royal interest was called at Oxford, where the ‘Whigs had no influence. Charles demanded that he had the right of naming the sheriffs of London, and acting upon this false assumption, nominated two violent Tories, who were ready to support the royal prerogative. Men who spoke against the Duke of York were heavily muleted. The infamous Jeffreys was recorder of London; the citizens, in fear of fines and executions, were divided amongst themselves; and the counteraction was complete when Shaftesbury, in despair of retrieving his position, threw up the cause of liberty and escaped to Holland, where a few weeks afterwards he died.

It now remained for Charles and his brother the Duke of York to strike at the party who were endeavoring to support the freedom of parliament and the rights of the constitution; and it was not difficult to do so, as some of its members were doubtless engaged in plans which might be called treasonable, though others, like Sidney and Russell, representing quite different opinions as to methods and results, were reformers who desired to act within the lines which the law gives to an assertion of public right.

In order to carry their plan into effect the reformers organized a select committee, called the “Council of Six.” The members of this council were Monmouth, Essex (who was the chief adviser), Sidney, Russell, Lord Howard (introduced by Sidney), and young Hampden, a scholar and a grandson of the Hampden. What the deliberations of this council were it is now difficult to ascertain, owing to the prejudiced sources from which information has to be derived. There can be no doubt, however, that consultations were frequently held as to the best course to pursue for resisting a government which aimed at nothing less than arbitrary power. It is reported that the object of this council was to organize an insurrection all over the country, and, with the help of the discontented Presbyterians in Scotland, to put an end to the tyranny of Charles and his brother. What was the exact extent of these designs it is impossible to determine, unless we believe in the statements of Lord Grey and Bishop Sprat-the two most prejudiced and partial narrators of the Rye House Plot. In all probability there was, as Lady Russell said, much talk about a general rising, which “only amounted to loose discourse, or at most, embryos that never came to anything.” She was convinced, she said, that it was no more than talk, “and ’tis possible that talk going so far as to consider, if a remedy to suppress evils might be sought, how it could be found.”

Whilst the Council of Six were meditating their plans, whatever they might be, an inferior order of conspirators were holding meetings and organizing an insurrection perfectly unknown to the council. The chief of these conspirators were West, an active man, who was supposed to be an Atheist; Colonel Rumsey, an officer who had served under Cromwell, and afterwards in Portugal; Ferguson, an active agent of the late Lord Shaftesbury; Goodenough, who had been under-sheriff of London; Lieutenant-colonel Walcot, a republican officer; and several lawyers and tradesmen. The aim of these men seems to have been desperate and criminal in the extreme. They talked openly about murdering the king and his brother, and even went so far as to organize a scheme for that purpose.

Among this band was one Rumbold, a maltster, who owned a farm called the Rye House, situated on the road to Newmarket, which sporting town Charles was accustomed to visit annually for the races. Rumbold laid before the conspirators a plan of this farm, and showed how easy it would be to intercept the king and his brother on their way home, fire upon them through the hedges, and then, when the deed of assassination was committed, escape by the by-lanes and across the fields. The murderous scheme of the maltster was, however, frustrated by Charles having been obliged to leave Newmarket eight days earlier than he had intended, owing to his house having taken fire. Treachery now put a stop to any further proceedings of the conspirators.

Among the minor persons engaged in the conspiracy was one Keeling, an Anabaptist, who, having failed as a salter, thought that as Oates and others had flourished so well in the trade of a witness, he might as well follow their example. He had been employed by Goodenough as a spy in the city, and was intimately acquainted with the movements and designs of the conspirators. Accordingly he went to Lord Dartmouth and told his tale, and was referred by his lordship to Mr. Secretary Jenkins. Jenkins took down his deposition, but said that unless his evidence was supported by another witness he could not proceed to the investigation of the matter. Keeling was, however, equal to the occasion, and induced his brother to corroborate his statements. The plot now authenticated by two witnesses, Jenkins thought it his duty to communicate the affair to the rest of the ministry. The younger Keeling, who had been compelled against his will to give evidence, secretly informed Goodenough that the plot had been discovered, and advised all engaged in it to flee beyond sea.

This news reaching Rumsey and West, who were inseparable allies, the two began to think it the safer policy to take a leaf out of the book of Keeling and reveal the whole plot-with a few additions. A house at Rye had been offered them by one Rumbold for the execution of their design. At this house forty men, well armed and mounted, commanded in two divisions by Rumsey and Walcot, were to assemble. On the return of the king from Newmarket, Rumsey with his division was to stop the coach and kill the king and the duke, whilst Walcot was to occupy himself in engaging with the guards. This done, they were to defend the moat till night, and then make their escape towards the Thames.

The details of the story once arranged, Rumsey and West had not to wait long before their veracity was put into requisition. Three days after Keeling’s discovery the plot broke out, and was the talk of all the town. Examinations were freely taken, and many suspected persons seized. A proclamation having been issued to secure those who could not be found, Rumsey and West, whose names were mentioned in the proclamation, delivered themselves up to justice of their own accord. And now their story of the plot was at once divulged. In spite of the little difficulties and improbabilities it contained-such as the absence of any important person to head the insurrection, the awkward fact of only being able to name eight out of the forty armed men who were to assemble at Rye, the ignorance as to how arms and horses were to be supplied, the very practicable idea of defending themselves within mud walls and a moat, and the like-the story was implicitly believed. As an agreeable addition to this manufactured revelation the new witnesses declared that they had heard ‘of the conferences that the Duke of Monmouth and the other lords had with those who were come from Scotland, but knew nothing of it themselves’ (a very safe and cautious reserve). Rumsey, however, said that he remembered the meeting at Shepherd’s and the talk about seizing the king’s guards. 1)

In this critical situation Lord Russell, though perfectly sensible of his danger, acted with the greatest composure. He had long ago told a friend that he was very sensible he should fall a sacrifice. Arbitrary government could not be set up in England without wading through his blood.

1) Ewald Life and Times of Algernon Sidney.

The day before the king arrived a messenger of the council was sent to wait at his gate to stop him if he had offered to go out; yet his back gate was not watched, so that he might have gone away if he had chosen it. Yet he thought proper to send his wife amongst his friends for advice. They were at first of different minds; but as he said he apprehended nothing from Rumsey, who had named him in his accusation, they agreed that his flight would look too much like a confession of guilt. This advice coinciding with his own opinion he determined to stay where he was. As soon as the king arrived a messenger was sent to bring him before the council.

When he appeared there the king told him that nobody suspected him of any design against his person, but that he had good evidence of his being in designs against his government. He was examined upon the information of Rumsey. When the examination was finished Lord Russell was sent a close prisoner to the Tower. Upon his going in he told his servant Taunton that he was sworn against, and they would have his life. Taunton said he hoped it would not be in the power of his enemies to take it. Lord Russell answered, “Yes; the devil is loose!”

It is not necessary to enter into the points of the trial, which followed an examination by the privy-council. The bench had been supplied with accommodating judges. Jeffreys was one of the counsel for the prosecution; an illegally returned jury was not allowed to be challenged; the witnesses were perjured, contradicted themselves, and swore to save their lives. One of them (Lord Howard), who had previously declared that he knew nothing that could hurt Lord Russell, was a man of such’ infamous character that the king said he “would not hang the worst dog he had upon his evidence.” Nevertheless his evidence was taken against the testimony of a number of honorable men.

The ground on which Lord Russell was sentenced to death was that he had violated the law in conspiring the death of the king. He argued that, granting the charge to be true (which he denied), it was not that of conspiring the death of the king, but “a conspiracy to levy war;” that this was not treason within the statute (which it was not); and that if it had been, a statute of Charles II. made the accusation null and void, because the time had expired to which the operation of it was limited.

His wife, Lady Rachel Russell, the daughter of the virtuous and noble Earl of Southampton, was his chief friend and counsellor. At his trial, wishing to have notes of the evidence, he asked whether he might have somebody to write for him. The Chief-justice Pemberton said, “Any of your servants shall assist you in writing anything you please.” “My lord,” said Russell, “my wife is here to do it.” And when the spectators turned their eyes and beheld the devoted lady rise up to assist her lord in this his uttermost distress, a thrill of anguish ran through the assembly.

Essex had been taken to the Tower, and while the perjured Howard was giving his evidence intelligence reached the court that in a fit of depression the noble lord had committed suicide. The attorney-general made use of the information to declare that Essex had killed himself to escape the hands of justice. The trial proceeded: the false witness, having recovered the shock of the dreadful news, went on with his evidence, and others swore to save their own lives. Before the jury withdrew Russell said to them, “Gentlemen, I am now in your hands eternally-my honor, my life, my all; and I hope the heats and animosities that are among you will not so bias you as to make you inclined to find an innocent man guilty. I call heaven and earth to witness that I never had a design against the king’s life. I am in your hands; so God direct you!” But the jury soon brought in a verdict of guilty; and Treby, recorder of London, who had formerly been an exclusionist, and who had been deeply engaged with Lord Shaftesbury in most of the city schemes and plots, pronounced the horrible sentence of death for high treason.

Many efforts were made to obtain the royal pardon; but Charles was inexorable, even though £ 100,000 was offered him by his lordship’s father the Duke of Bedford, through the French mistress the Duchess of Portsmouth. Russell’s friends urged him to petition both the king and the Duke of York, and he complied by writing letters, which were of no avail. Lord Cavendish, his friend, offered to manage his escape by changing clothes and remaining at all hazards to himself; but Russell refused, and prepared to die with Christian piety. There are few more affecting accounts than that of the last hours of this nobleman, who seems to have been greatly beloved by all who knew him; while the conduct of his wife, who long survived him, and saw the downfall of the house of Stuart, is an admirable example of courage and devotion. She threw herself at the king’s feet and pleaded with many tears the merit and loyalty of her father as an atonement for those errors his trial, wishing to have notes of the evidence. he asked whether he might have somebody to write for him. The Chief-justice Pemberton said, ” Any of your servants shall assist you in writing anything you please.” “My lord,” said Russell, “my wife is here to do it.” And when the spectators turned their eyes and beheld the devoted lady rise up to assist her lord in this his uttermost distress, a thrill of anguish ran through the assembly.

Essex had been taken to the Tower, and while the perjured Howard was giving his evidence intelligence reached the court that in a fit of depression the noble lord had committed suicide. The attorney-general made use of the information to declare that Essex had killed himself to escape the hands of justice. The trial proceeded: the false witness, having recovered the shock of the dreadful news, went on with his evidence, and others swore to save their own lives. Before the jury withdrew Russell said to them, “Gentlemen, I am now in your hands eternally-my honor, my life, my all; and I hope the heats and animosities that are among you will not so bias you as to make you inclined to find an innocent man guilty. I call heaven and earth to witness that I never had a design against the king’s life. I am in your hands; so God direct you!” But the jury soon brought in a verdict of guilty; and Treby, recorder of London, who had formerly been an exclusionist, and who had been deeply engaged with Lord Shaftesbury in most of the city schemes and plots, pronounced the horrible sentence of death for high treason.

Many efforts were made to obtain the royal pardon; but Charles was inexorable, even though £ 100,000 was offered him by his lordship’s father the Duke of Bedford, through the French mistress the Duchess of Portsmouth. Russell’s friends urged him to petition both the king and the Duke of York, and he complied by writing letters, which were of no avail. Lord Cavendish, his friend, offered to manage his escape by changing clothes and remaining at all hazarcds to himself; but Russell refused, and prepared to die with Christian piety. There are few more affecting accounts than that of the last hours of this nobleman, who seems to have been greatly beloved by all who knew him; while the conduct of his wife, who long survived him, and saw the downfall of the house of Stuart, is an admirable example of courage and devotion. She threw herself at the king’s feet and pleaded with many tears the merit and loyalty of her father as an atonement for those errors with which honest. however mistaken, principles had seduced her husband. It is said that Charles refused her even a reprieve of six weeks, saying, “How can I grant that man six weeks, who, if it had been in his power, would not have granted me six ours.

Finding all applications vain, Lady Russell collected courage and endeavored by her example to strengthen the resolution of her unfortunate lord. He exhibited no fear of his sentence. “His whole behavior,” says Burnet, “looked like a triumph over death.” He said he felt none of those transports that some good people felt; but he had a full calm in his mind, no palpitation at heart, nor trembling at the thoughts of death. He was much concerned at the cloud that seemed to be now over his country; but he hoped his death would do more service than his life could have done. He asked Burnet to assist him in suggesting the way in which he should draw up a paper to leave behind him at his death, and he was three days employed for some time in the morning to write out his speech. He ordered four copies to be made of it, all which he signed; and gave the original, with three of the copies, to his lady, and kept the other to give to the sheriff on the scaffold. He also wrote to the king, in which he asked pardon for everything he had said or done contrary to his duty, protesting he was innocent as to all designs against his person or government, and that his heart was ever devoted to that which he thought was his majesty’s true interest.

He added that though he thought he had met with hard measures, yet he forgave all concerned in it from the highest to the lowest, and ended hoping that his majesty’s displeasure at him would cease with his own life, and that no part of it should fall on his wife and children. “The day before his death,” says Burnet, “he received the sacrament from Tillotson with much devotion: and I preached two short sermons to him, which he heard with great affection; and we were shut up till towards the evening. Then he suffered his children that were very young, and some few of his friends, to take leave of him: in which he maintained his constancy of temper, though he was a very fond father. He also parted from his lady with a composed silence; and as soon as she was gone, he said to me, ‘The bitterness of death is passed;’ for he loved and esteemed her beyond expression, as she well deserved it in all respects. She had that command of herself so much, that at parting she gave him no disturbance.”

The substance of the paper delivered to the sheriff was first a profession of his religion and of his sincerity in it: that he was of the Church of England, but wished all would unite together against the common enemy; that Churchmen would be less severe, and Dissenters less scrupulous. He owned he had a great zeal against Popery, which he looked on as an idolatrous and bloody religion; but that though he was at all times ready to venture his life for his religion or his country, yet that would never have carried him to a black or wicked design. No man ever had the impudence to move to him anything with relation to the king’s life; he prayed heartily for him, that in his person and government he might be happy both in this world and the next. He protested that in the prosecution of the Popish plot he had gone on in the sincerity of his heart, and that he never knew of any practice with the witnesses. He owned he had been earnest in the matter of the exclusion, as the best way in his opinion to secure both the king’s life and the Protestant religion, and to that he imputed his present sufferings; but he forgave all concerned in them, and charged his friends to think of no revenges. He thought his sentence was hard, upon which he gave an account of all that had passed at Shepherd’s. From the heats that were in choosing the sheriffs he concluded that matter would end as it now did, and he was not much surprised to find it faIl upon himself; he wished it might end in him. Killing by forms of law was the worst kind of murder. He concluded with some very devout ejaculations.

This is the synopsis of Lord Russell’s paper as delivered to the sheriff; and immediately after the execution, to which he went with the greatest composure and religious fortitude, copies of the document were printed, and distributed all over London. The king and the duke, with their supporters, may well have felt that they had not triumphed after all, for this paper must have contributed greatly to the events which followed, and to the final release of the country from the Stuarts. Within six years after the execution of Lord Russell, James II., when leaving his throne, and, seeking for aid, had the meanness or the stupidity to apply to the aged Earl of Bedford for assistance. “My lord,” said the fugitive king, “you are an honest man, have great credit, and can do me signal service.” ” Ah! sir,” replied the earl, “I am old and feeble, but I once had a son.” The king is said to have been so struck with this reply that he was silent for some minutes.

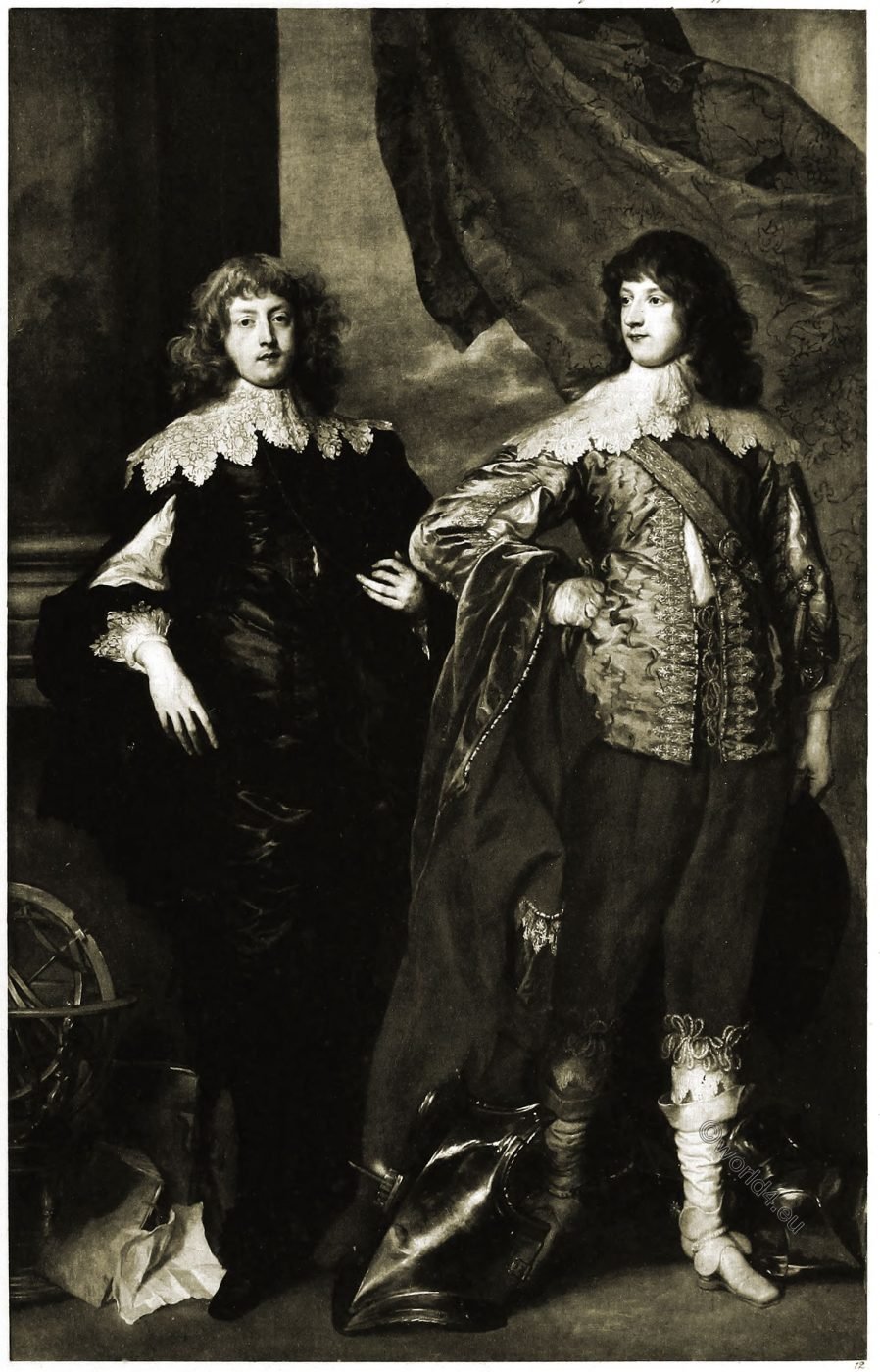

Source: Pictures and royal portraits illustrative of English and Scottish history, from the introduction of Christianity to the present time : Engraved from important works by distinguished modern painters, and from authentic state portraits. With descriptive historical sketches by Thomas Archer. London: Blackie & son, 1880.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.