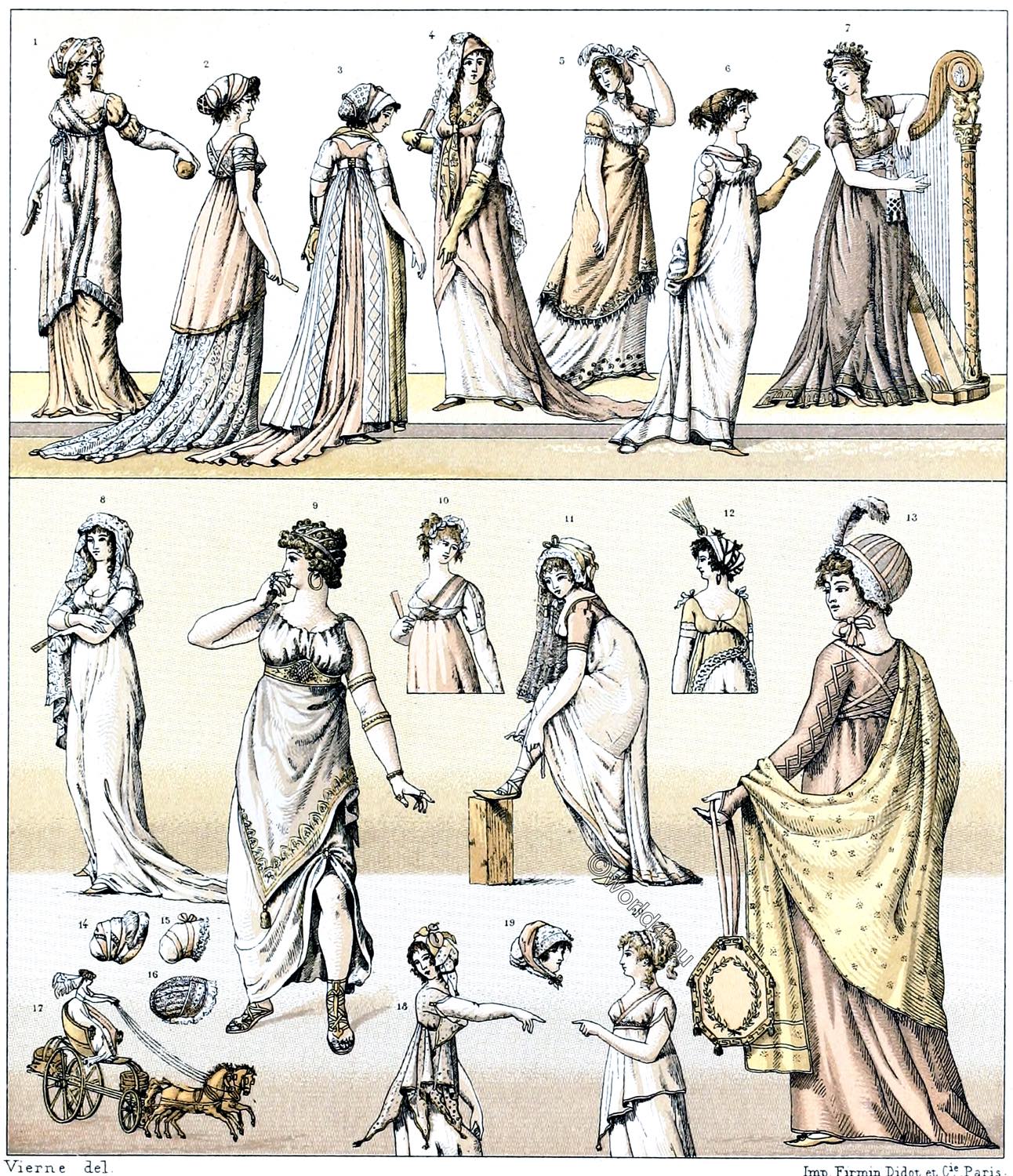

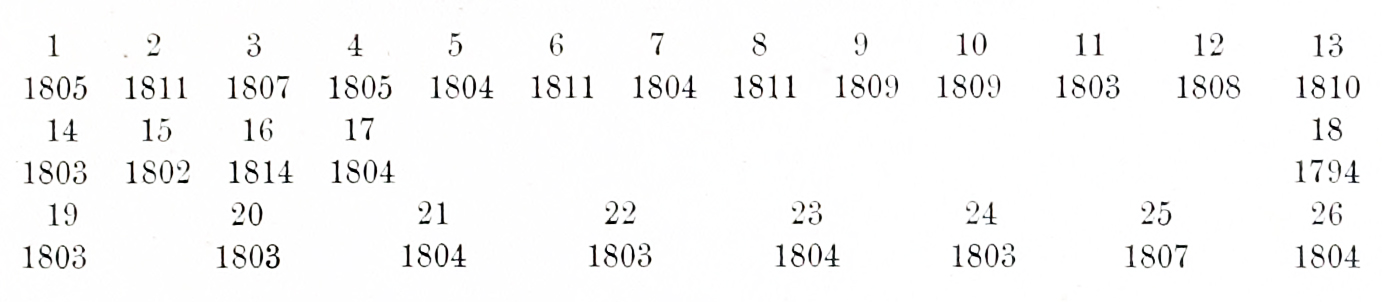

FRANCE XVIII and XIX HUNDRED.

WOMEN’S DRESSES. SHAWLS.

Directorate, Consulate, Empire.

While until the mid-nineties of the 18th century only wide crepe breast cloths were worn (no. 18), towards the end of the century fine cashmere fabrics and thus also scarves and shawls came into use. The figures on this panel show the diverse forms in which the scarf – originally an elongated square piece of fabric with more or less wide embroidery at the ends – was worn and draped, sometimes as a neck and breast cloth (Nos. 19-21), sometimes as a complete wrapping of the upper body (Nos. 9, 11, 23).

The first fabrics made of cashmere wool came to Paris as early as 1775, but found no mercy in the eyes of the ladies at that time. It was not until after the Egyptian expedition of the first consul (Napoleon Bonaparte) that the fashion for wearing Indian scarves spread more and more until, at the turn of the century, it became general and the scarf was considered an indispensable part of the female toilet.

Kashmir then no longer supplied the fabrics alone. Finally, scarves were made in all sizes according to the seasons and from the most diverse fabrics, from cloth, wool, silk, cotton, East Indian cattun and lace. Of course, the finest fabrics were still in use, and it is said that the women tested their fineness by trying to pull the scarves through their rings.

When the fashion of scarves came up, the ladies did not part with them. They wore them on the promenade, in society, at the ball. The scarf was a welcome addition to the “Greek” costume that appeared at the same time. On the one hand, it was an opportunity to drape oneself in the antique style and to wrap oneself in it, following the example of the antique statues (no. 23), and on the other hand, to cover the nakedness of the body, which the Greek costume revealed all too generously.

Apart from these wide and large scarves, however, the narrow, sashlike ones, which only protected the neck, were also in fashion (No. 21). The scarf reached the peak of popularity when a dance, le pas du schall, was held in its honour, with which the beautiful Countess of Hamilton achieved great success in the distinguished society. A light silk scarf was used for this dance (No. 6).

During the Consulate and the first half of the Empire, the shawls were monochrome with wide borders embroidered with palm trees or flowers on a different coloured ground. At that time they were called Turkish shawls. Yellow, green, white and ponceau-red (cochineal red) came into fashion one after another.

Around 1811, people wore blue scarves à la Marie-Louise with large palm trees on a wide, white border. To facilitate the drapery and to preserve the drapery once arranged, golden acorns were attached to the ends of the scarf or lead was sewn into the corners (Nos. 11, 22 -24).

(According to several simultaneous fashion magazines.)

Source: History of the costume in chronological development by Auguste Racinet. Edited by Adolf Rosenberg. Berlin 1888.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.