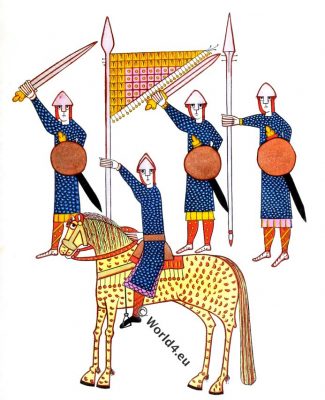

Spanish warriors from a MS. of the end of the eleventh century

EVERY step which we trace back in the history of the nations of Europe brings us nearer to a uniformity of costume. Fashions in dress did not begin to go through that quick vicissitude of change which characterizes modern times, till towards the thirteenth century. We can trace little variation in the dress of the Anglo-Saxons during the whole period of their history, and not much between that of the Anglo-Saxons and the Franks.

As people became more distinctly separated from each other by national jealousies, and long and obstinate wars, the new fashions adopted in one country were more slowly communicated to another, and thus the similarity of costume becomes separated by distance of date; while some countries became so entirely estranged from each other during a long period, that the resemblance of costume and the simultaneous variation was altogether lost.

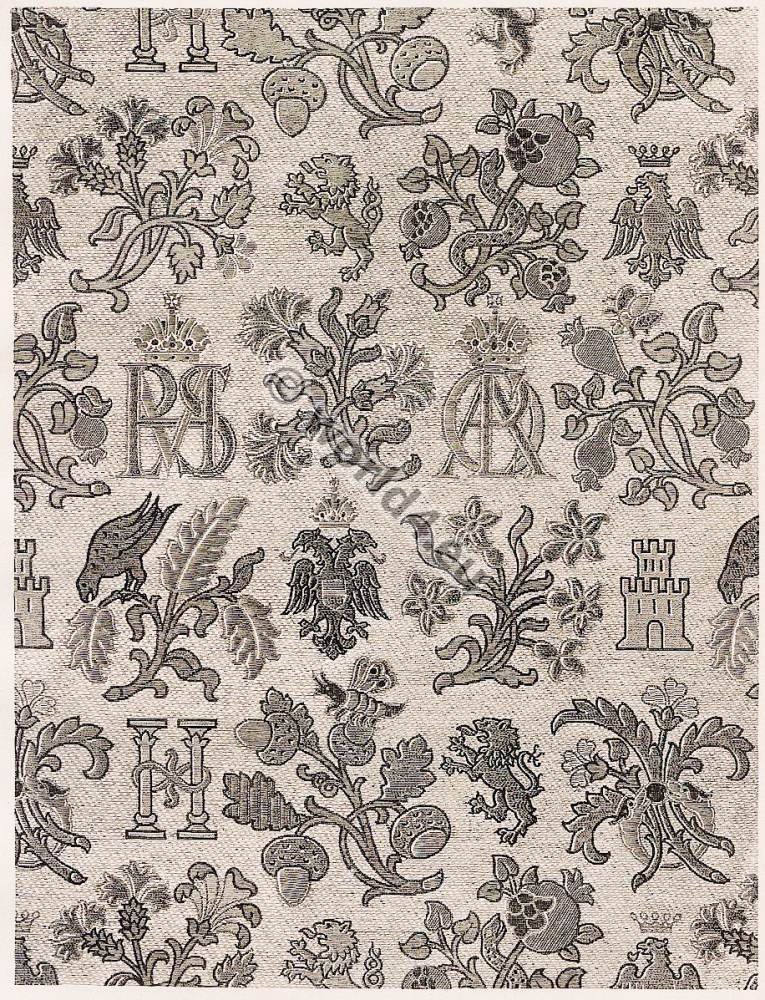

The figures which form our plate represent Spanish warriors of the latter part of the eleventh century, and are interesting on account of their remarkable resemblance to the Anglo-Norman soldiers on the celebrated Bayeaux Tapestry. This resemblance is observable in the style of drawing, as well as in the costume. It is probable that the military habits of this period were in part borrowed from the Saracens: and this supposition is strengthened by the fact that Arabic inscriptions in Cufic characters are found among the ornaments of several robes still preserved, which belonged to German and Frankish barons of the tenth and eleventh centuries.

One peculiarity of the armour of our Spanish warriors is the round shield, with the elegant ornaments on the disc. We give in the margin a specimen of one of these shields on a larger scale, from another part of the manuscript from which these figures are taken.

The manuscript which has furnished these figures (MS. Additional, No. 11,695) is one of the most valuable of the treasures of that kind recently acquired by the British Museum. It is a large folio on vellum, in a beautiful state of preservation, containing a comment upon and interpretation of the Apocalypse, that fruitful source of design to the medieval artists. It was executed in the monastery of Silos in the diocese of Burgos (Old Castile), having been begun under the abbot Fortunius, carried on after his death during the abbacy of Nunnus (Nunez), and completed in the time of abbot John, in the year 1109.

This information we obtain from the manuscript itself; and as it thus appears to have occupied not less than twenty years in writing and illuminating, we may with propriety consider it as representing the costume of the latter part of the eleventh century. This manuscript was purchased in 1840 by the trustees of the British Museum of the Comte de Survilliers (Joseph Buonaparte).

The style of the drawings in this manuscript is itself half Saracenic. The elegance of the ornaments contrasts strongly with the unskilful rudeness in the designs of men and animals, a circumstance which reminds us of the repugnance among the Arabs to drawing men and living beings. It is in many respects a valuable monument of art, and proves clearly the intercourse which existed between the Moors and the Christians in Spain.

Throughout the volume the architecture of the buildings is altogether Moorish—the walls covered with arabesque ornaments, and the remarkable horse-shoe arches, appear on almost every page, and show the accuracy of the term Saracenic adopted by architectural writings. The character of the ornamented initial letters, of which an example is given at the beginning of the present article, bears a close resemblance to that observed in many of our Anglo-Saxon manuscripts of the tenth century.

One of the most interesting groups in this volume, is that representing two minstrels, or jongleurs, given at the foot of the preceding page. They appear to be dancing on a kind of wooden stilts. There are many reasons for supposing that the character of the minstrel, as it existed in Christian Europe during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, was of Arabian origin, as are without doubt many of the tales and stories which they were in the habit of rehearsing; and these figures of Spanish jongleurs, so completely oriental in their appearance, are a valuable addition to our materials for the history of that singular class of medieval society.

Our plate is taken from folio 223 of the manuscript just described; the shield and sword belong to a large in-drawn figure on folio 194; the minstrels are from folio 86; and the initial letter from folio 25.

Source: Dresses and Decorations of the Middle Ages by Henry Shaw F.S.A. London William Pickering 1843.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.