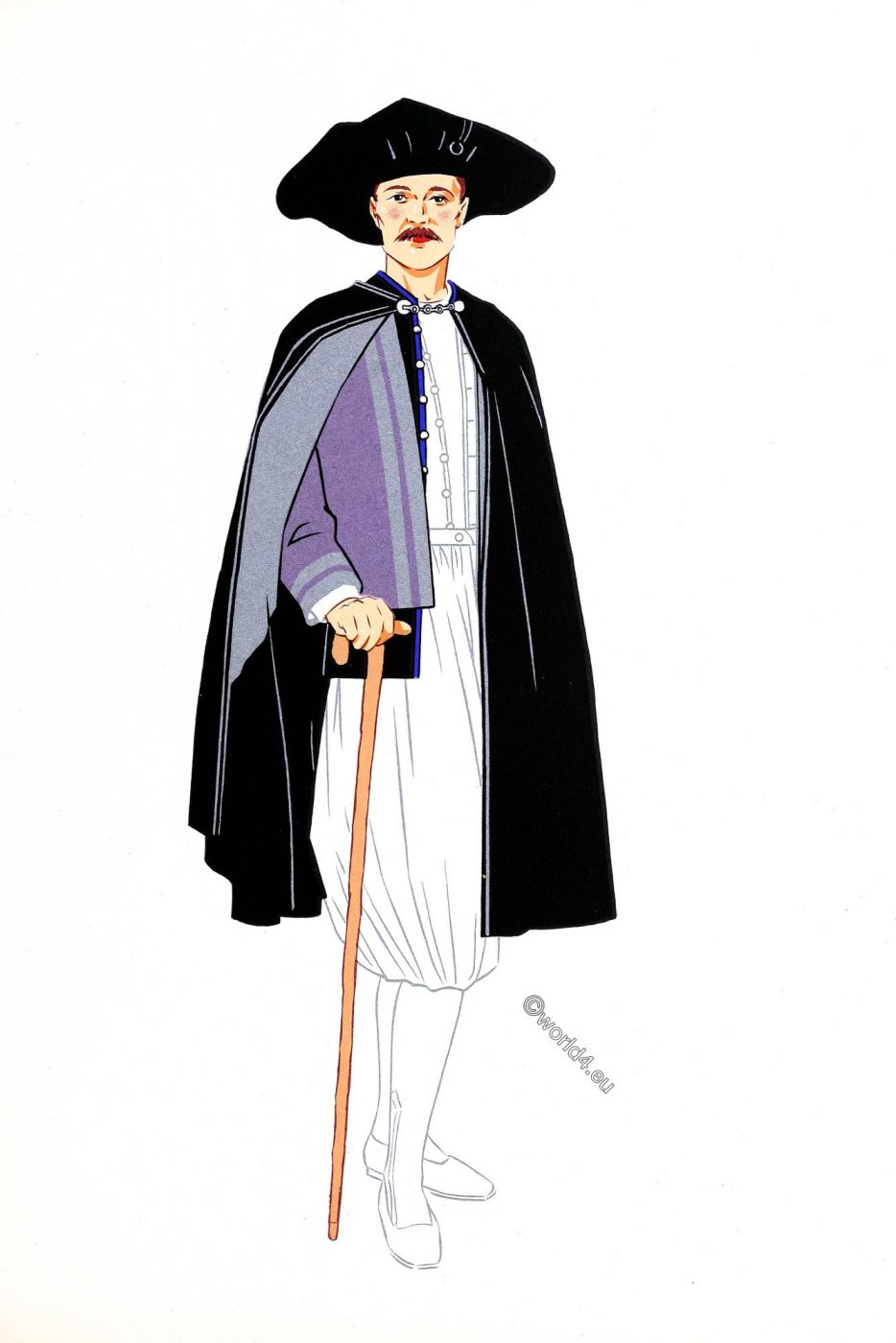

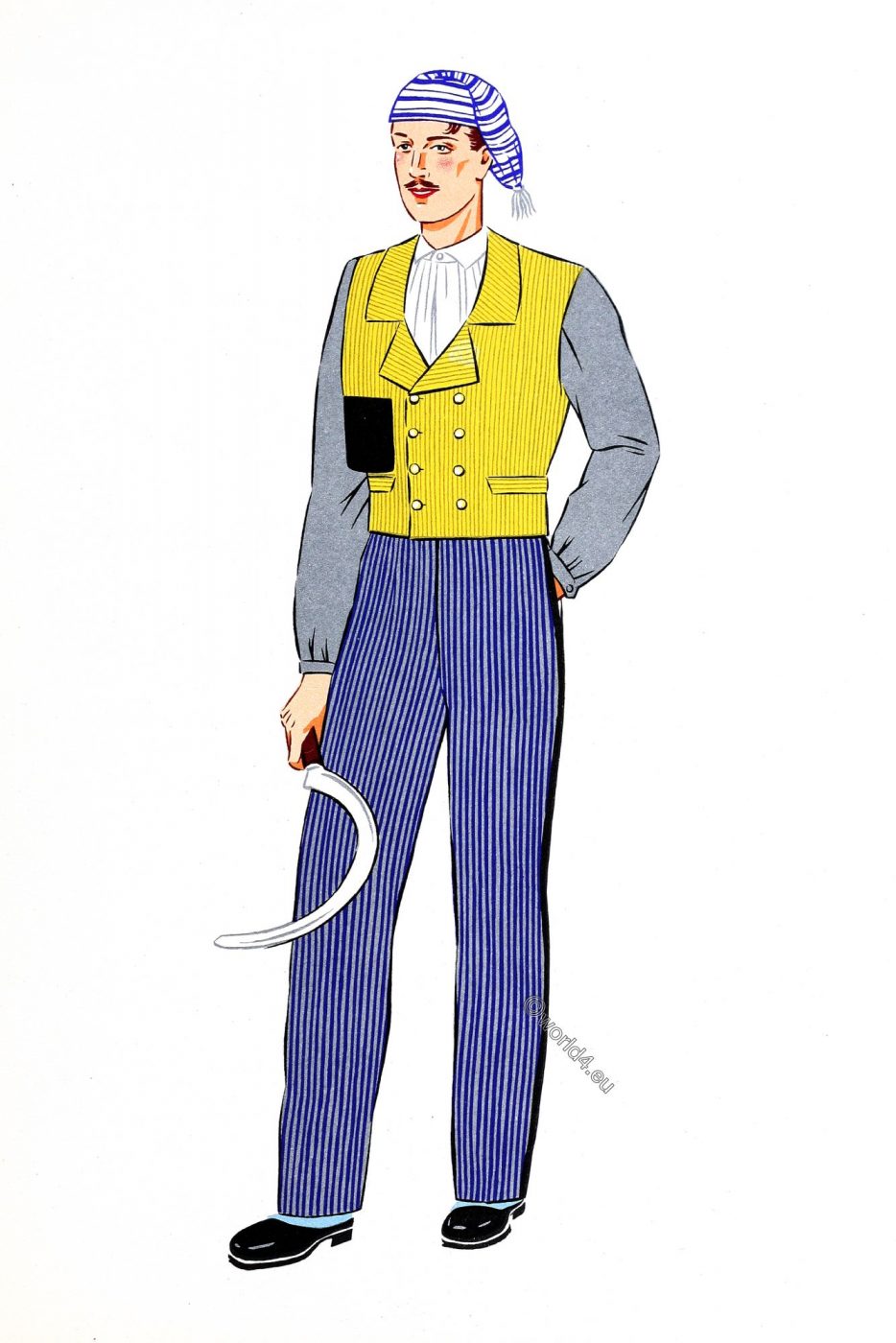

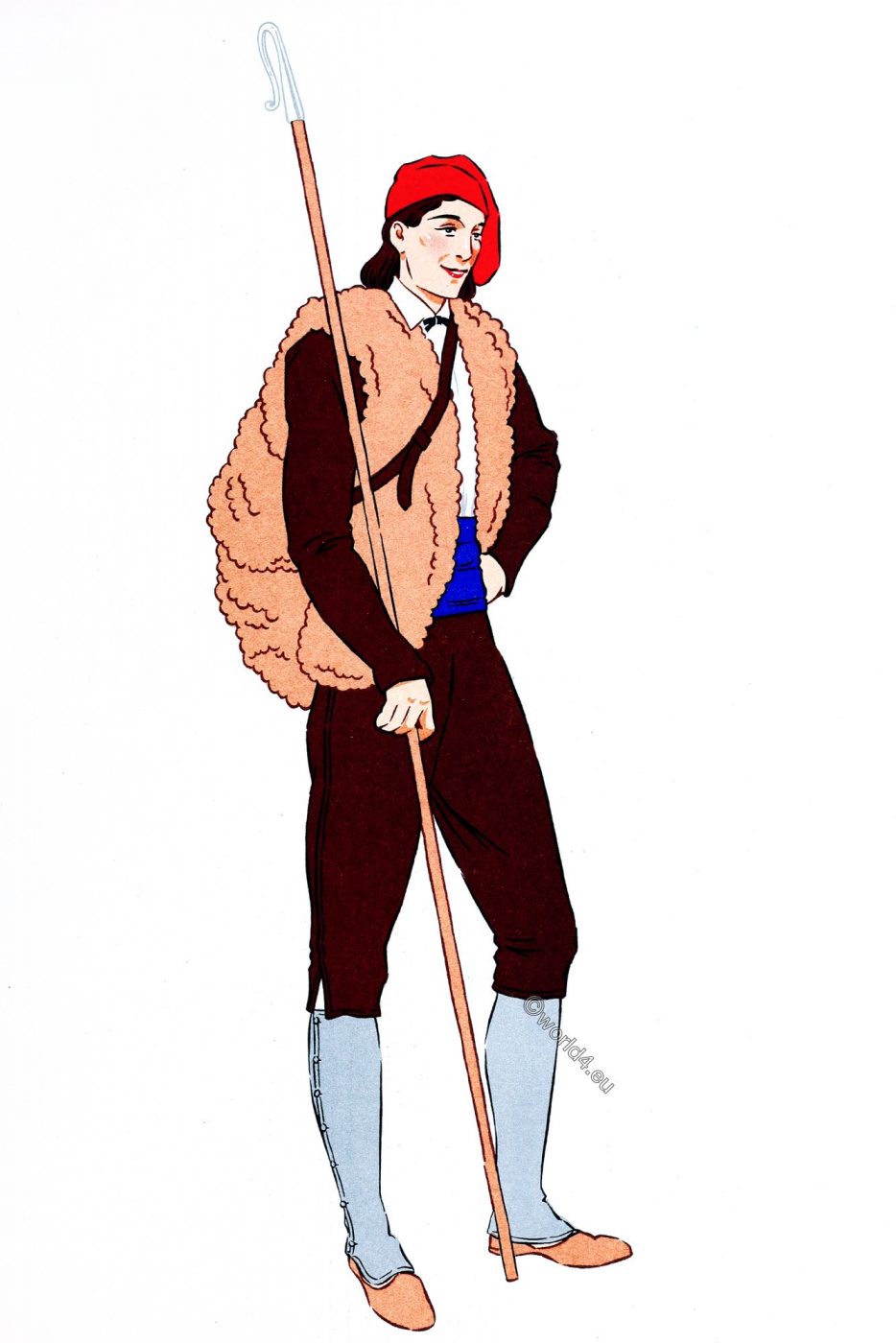

Costumes Nationaux de Alsace, Brittany, Calvados, Landes, Pyrénnées region, Normandy, Champagne-Ardenne, Lorraine, Franche-Comté, Bourgogne, Bresse, Bourbonnais, Savoy, Auvergne, Basque Country and others.

Traditional French national costumes. Les costumes regionaux de la France. Costumes traditionnels français.

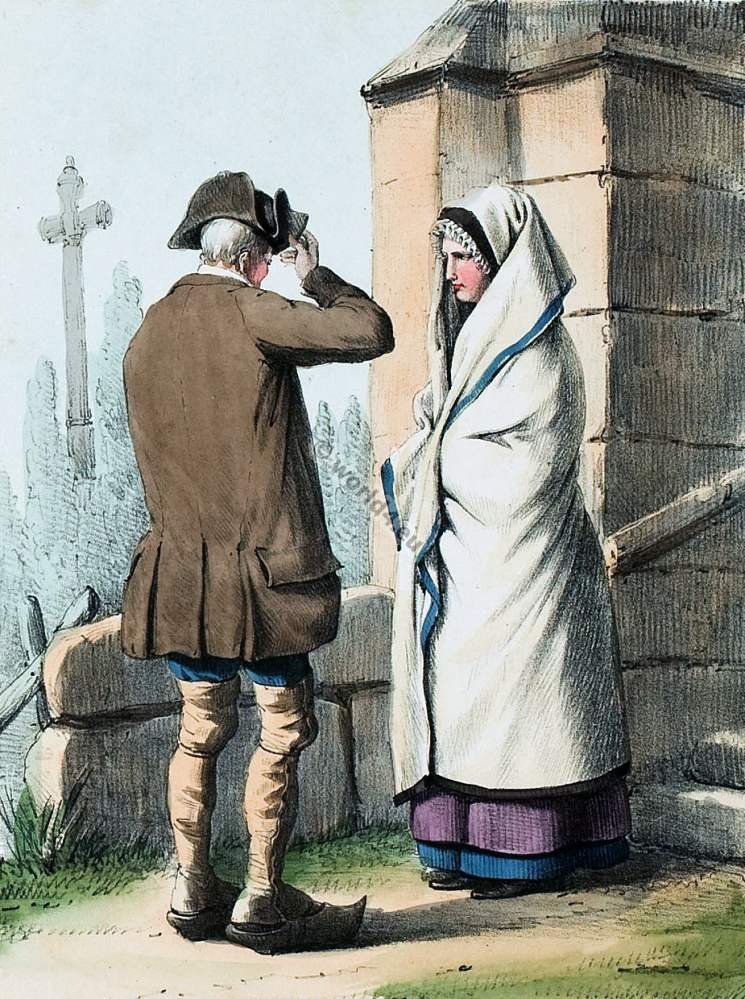

BRITTANY

Brittany (Breton Breizh) is a West French region. Today it consists of the departments Côtes-d’Armor (bret. Aodoù-an-Arvor), Finistère (bret. Penn-ar-Bed), Ille-et-Vilaine (bret. Il-ha-Gwilen) and Morbihan (bret. Mor-bihan). Capital of the region is Rennes (bret. Roazhon).

The department of Loire-Atlantique (bret. Liger-Atlantel), which belongs to the historical Bretagne but not to the modern administrative region of the same name, was split off in 1941 together with the original Breton capital Nantes (bret. Naoned).

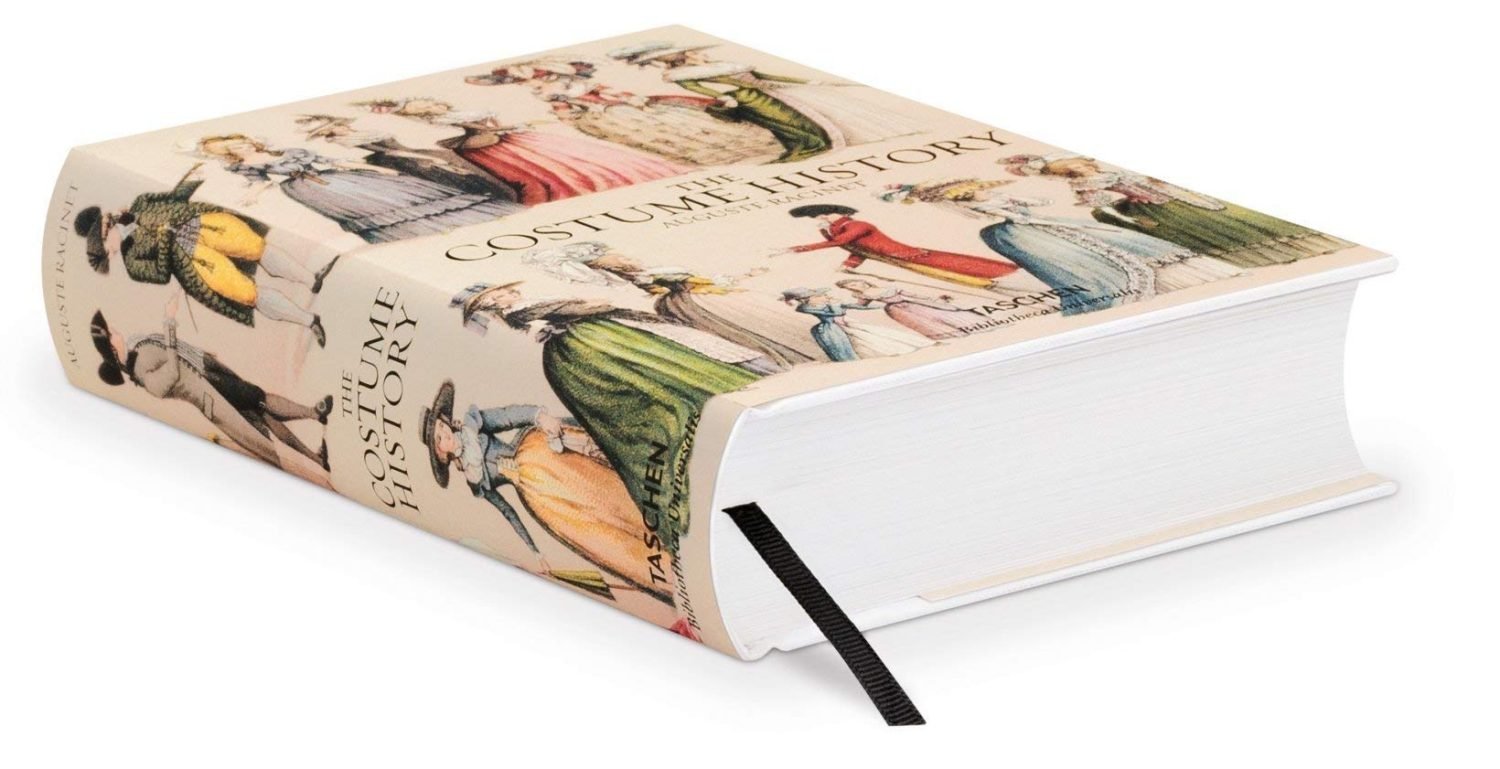

Auguste Racinet. The Costume History by Françoise Tétart-Vittu.

Racinet’s Costume History is an invaluable reference for students, designers, artists, illustrators, and historians; and a rich source of inspiration for anyone with an interest in clothing and style. Originally published in France between 1876 and 1888, Auguste Racinet’s Le Costume historique was in its day the most wide-ranging and incisive study of clothing ever attempted.

Covering the world history of costume, dress, and style from antiquity through to the end of the 19th century, the six volume work remains completely unique in its scope and detail. “Some books just scream out to be bought; this is one of them.” ― Vogue.com

Continuing

NORMANDY

Normandy is today the name of a French region. Since 996 A.D., forerunners have existed as a historical province in the north of France. The area is divided into the lower Seine area (the former region Haute-Normandie) north of Paris and the country towards the west (former region Basse-Normandie) with the peninsula Cotentin. The Normandy region includes the French departments of Calvados, Eure, Manche, Orne and Seine-Maritime.

Related

CHAMPAGNE

Champagne-Ardenne is a former region in the northeast of France, which consisted of the departments Ardennes, Aube, Marne and Haute-Marne. It was named after the historical landscape of Champagne and the Ardennes mountains. Since 2016, the region has formed the western part of the new Grand Est region. Capital of the region was Châlons-en-Champagne, the largest and historically most important city is Reims.

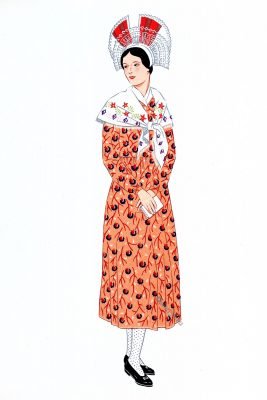

ALSACE

Alsace is a cultural and historical region from eastern France to the border with Germany and Switzerland. It is made up of the Haut-Rhin and Bas-Rhin departments. Its inhabitants are called Alsaciens.

Continuing

LORRAINE

Lorraine is a landscape in the northeast of France. It is the central part of the Grand Est region. From 1960 to the end of 2015, Lorraine, which dates back to the historic Duchy of Lorraine, formed its own region with the capital Metz, consisting of the departments of Meurthe-et-Moselle, Meuse, Moselle and Vosges.

FRANCHE-COMTE

Until 2015, Franche-Comté was a region in the east of France. It consisted of the départements of Doubs, Jura, Haute-Saône and Territoire de Belfort. Today the area belongs to the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region.

BURGUNDY

Burgundy (French Bourgogne) is a landscape in the centre of France. From 1956 to 2015, it was a region in its own right, made up of the departments of Côte-d’Or, Nièvre, Saône-et-Loire and Yonne. The capital was Dijon. The Burgundy region merged with the Franche-Comté region to form Bourgogne-Franche-Comté.

BRESSE

Bresse is an old province in eastern France. Located between the regions of Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes and Bourgogne-Franche-Comté, stretching from the Dombes in the south to the river Doubs in the north and from the Saône in the west to the Jura in the east. The inhabitants of the landscape are called Bressans (or the female inhabitants Bressanes).

BOURBONNAIS

The Duchy of Bourbon, more commonly known as Bourbonnais, is a French historical and cultural region. The main town of this former province is Moulins and its territory corresponds approximately to the department of Allier in the Auvergne region, but some portions are located in neighbouring departments, such as Puy-de-Dôme and Cher (arrondissement de Saint-Amand-Montrond), which merged into the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region in 2016.

SAVOY

Savoy (French Savoie, Italian Savoia, Francoprovençal Savouè) is a landscape which today essentially extends to the French départements of Haute-Savoie and Savoie in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region.

Saint-Colomban-des-Villards is a French municipality in the department of Savoie in the region of Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes. It is is situated about 38 kilometres south-east of Chambéry and about 40 kilometres east-northeast of Grenoble on the Glandon, which originates in the municipality. Here lies the ski area Les Sybelles.

Saint-Sorlin-d’Arves is a municipality in the Savoy in France. It belongs to the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region, the Savoie department, the Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne arrondissement and the Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne canton.

Sainte-Foy-Tarentaise is a French commune located in the Savoie department, in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region. It is located about 75 kilometres east of Chambéry and about 39 kilometres south-east of Albertville on the border to the Valle d’Aosta in Italy.

AUVERGNE

The Auvergne (Occitan Auvèrnhe) is a landscape and one of the historical provinces of central France, located in the heart of the Massif Central. From 1960 to 2015, Auvergne was an administrative region made up of the departments of Puy-de-Dôme, Cantal, Haute-Loire and Allier. The capital of the region was Clermont-Ferrand.

BASQUE COUNTRY

The Basque Country (Basque Euskal Herria or Euskadi, Spanish País Vasco or Vasconia, French Pays Basque) is a region located at the southern tip of the Bay of Biscay on the Atlantic Ocean on the territory of the modern states of Spain and France. The French Basque Country, in the Basque called Iparralde (“Northern Basque Country”), forms the western part of the French department of Pyrénées-Atlantiques.

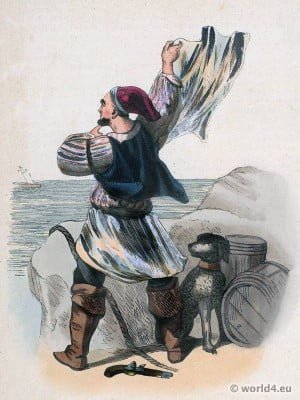

SABLES D’OLONNE

Les Sables-d’Olonne is a French port, fishing and bathing town in the Vendée département in the Pays de la Loire region on the Atlantic Ocean.

PROVENCE

The Provence extends from the Rhône via the Provençal foothills of the Alps and the coastal massif of the Maures to the Maritime Alps (Alpes Maritimes) and the Cottian Alps (Queyras and Haute Ubaye) on the border with the Italian regions of Piedmont and Liguria.

Arles is a city on the banks of the Rhone in the Provence region of southern France. It is famous as a source of inspiration for Van Gogh’s paintings. Arles was once the provincial capital of the Roman Empire and is also famous for the many remains of this period, including the amphitheatre of Arles, which now hosts theatrical performances, concerts and bullfights.

Nice, the capital of the Alpes-Maritimes département, is situated on the pebble-lined banks of the Baie des Anges on the French Riviera. The city was founded by the Greeks and was a popular resort for the European upper class in the 19th century.

The Farandole, from Provençal Farandoulo, is a historical Provençal folk dance in fast 6/8 time, in which an open round dance, led by a dancer, dances various figures. The musical accompaniment is provided by a player with a one-hand flute and a tambourine, behind whom the dancers are wandering through the streets. The dancers are danced in a chain of couples holding hands or connected by cloths. They move on in spirals and entanglements.

Georges Bizet composed a cheerful Farandole in his acting music for Alphonse Daudet’s L’Arlesienne. In the ballet Sleeping Beauty there is a Farandole at the beginning of the second act. Also in the opera “Mireille” by Charles Gounod a Farandole is played at the beginning of the second act.

Félix Gras, dancing the farandole, under the ramparts of Avignon, with his wife and daughters. Félix Gras (1844 – 1901) was a Provençal poet and writer. (Le costume en Provence by Jules-Charles Roux. Paris, Bloud 1909.)

BORDEAUX

Bordeaux (Occitan Bordèu) is a university city and the political, economic and scientific centre of the French southwest. Its inhabitants call themselves Bordelais. It is famous for its Bordeaux wine and cuisine, but also for its architectural and cultural heritage.

PYRENEES

The Pyrenees are a mountain range in southwestern Europe. The Pyrenees chain crosses two regions and six French departments: from east to west the Occitanie (Pyrénées-Orientales, Aude, Ariège, Haute-Garonne and Hautes-Pyrénées) and Nouvelle-Aquitaine (Pyrénées-Atlantiques) regions.

Eaux-Bonnes is a municipality in the Département Pyrénées-Atlantiques in the region Nouvelle-Aquitaine. The municipality belongs to the district of Oloron-Sainte-Marie and the canton of Oloron-Sainte-Marie-2 (until 2015: Canton Laruns).. The inhabitants are called Eaux-Bonnais or Eaux-Bonnaises.

The Val d’Aran is a valley in the heart of the Spanish Pyrenees on the border with France. The valley is linked to the French Gascony not only geographically, but also culturally, linguistically and economically.

Arrien-en-Bethmale is a French municipality in the Ariège département in the Occitan region. It belongs to the canton of Couserans Ouest and the arrondissement of Saint-Girons.

LOZÈRE

The département of Lozère is the French département with the serial number 48. It is located in the south of the country in the Occitan region and is named after the Mont Lozère massif in the Cevennes National Park.

CORSICA

Corsica (French: Corse) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea, largely made up of high mountains, and politically a French territorial entity with special status.

Région de l’Alsace en France.

Les costumes regionaux de la France. Deux cents aquarelles par G. De Gardilanne et E.W. Moffat. Avec un texte historique par Henry Royère et une préface par la Princesse Bibesco.

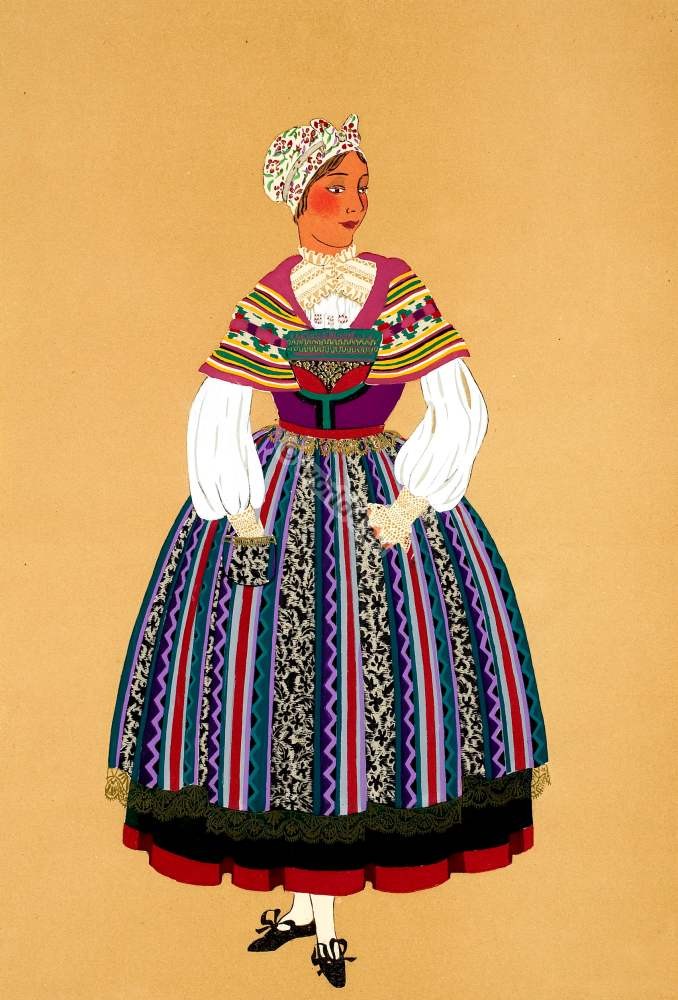

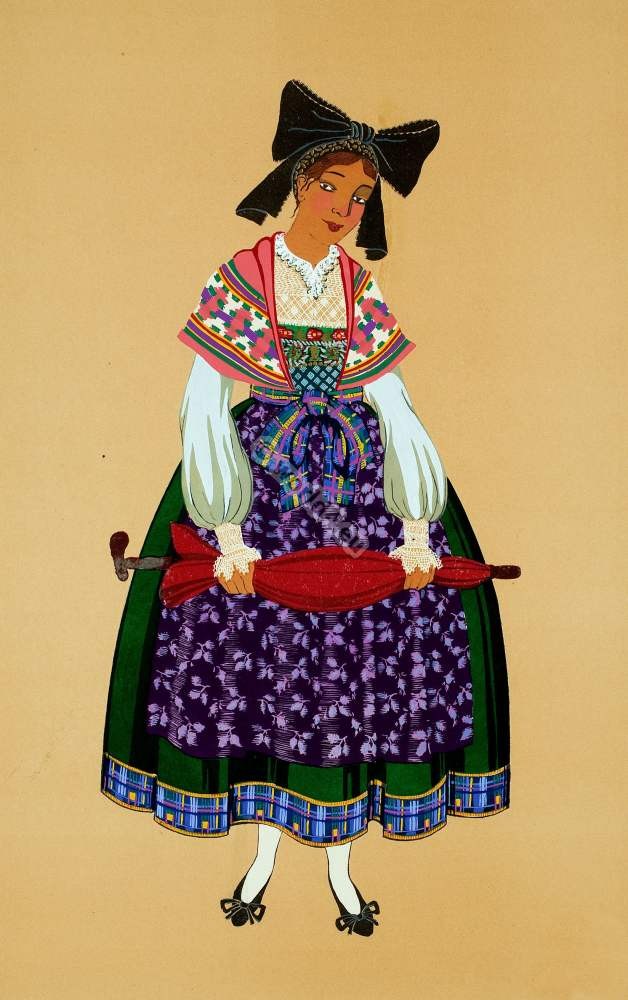

Brittany region.

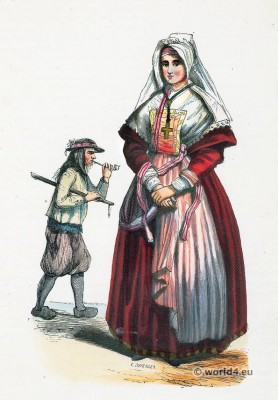

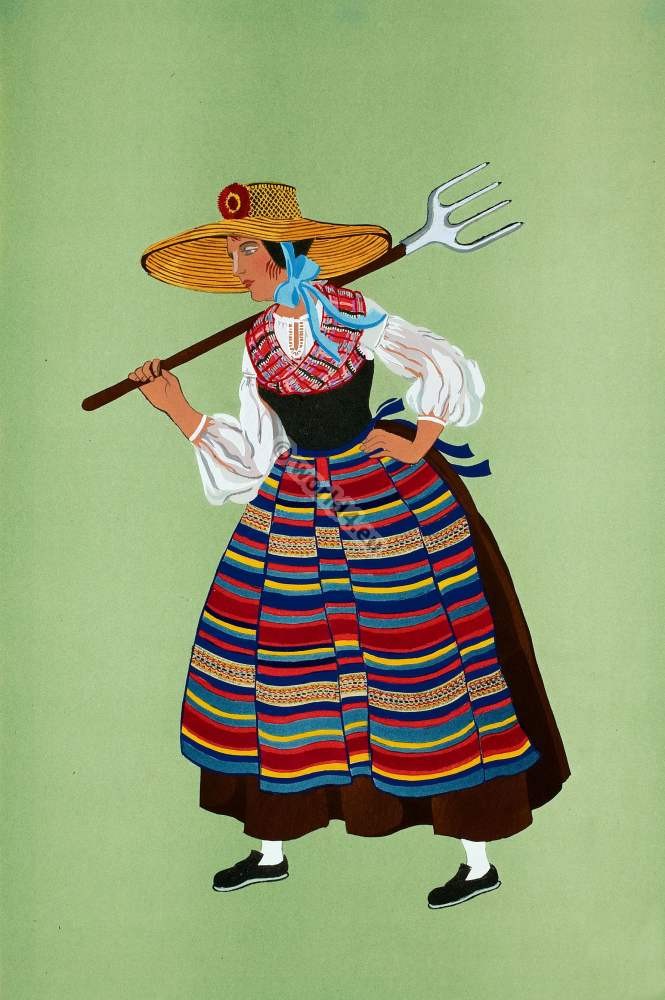

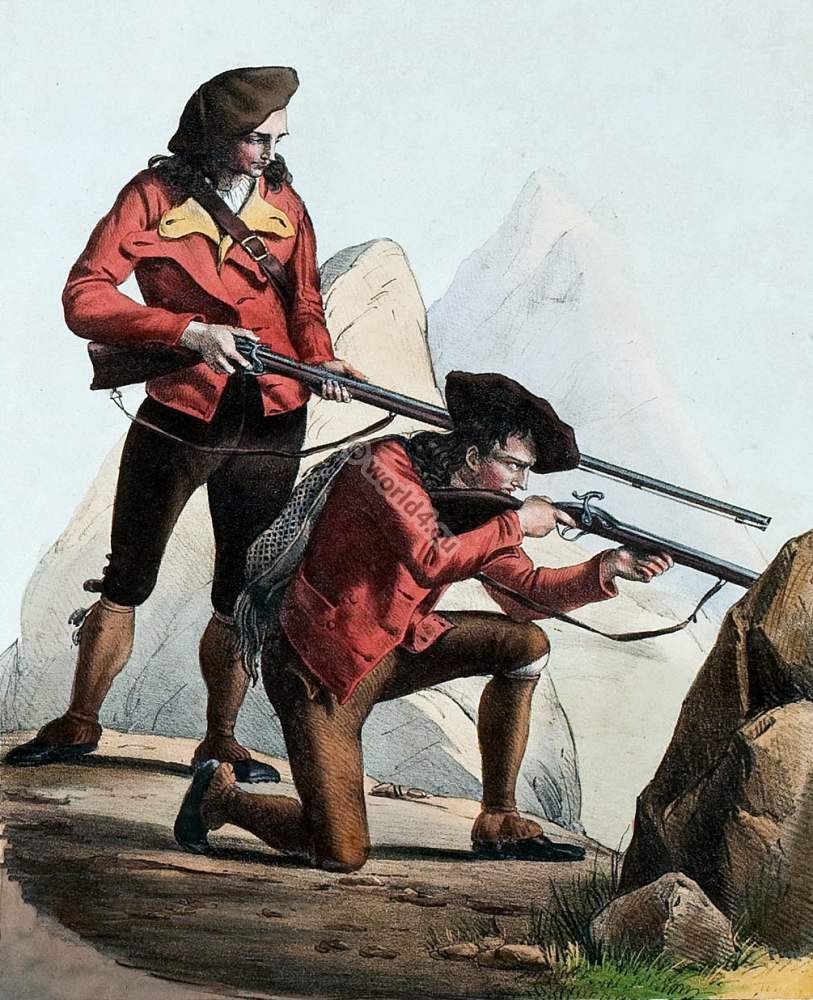

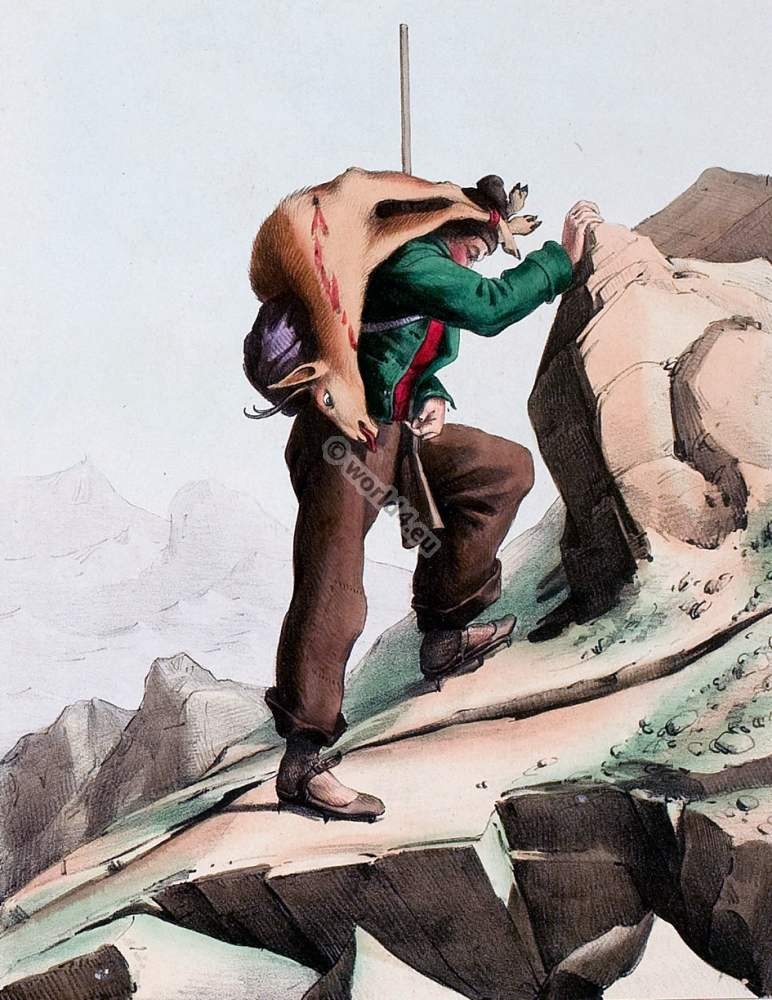

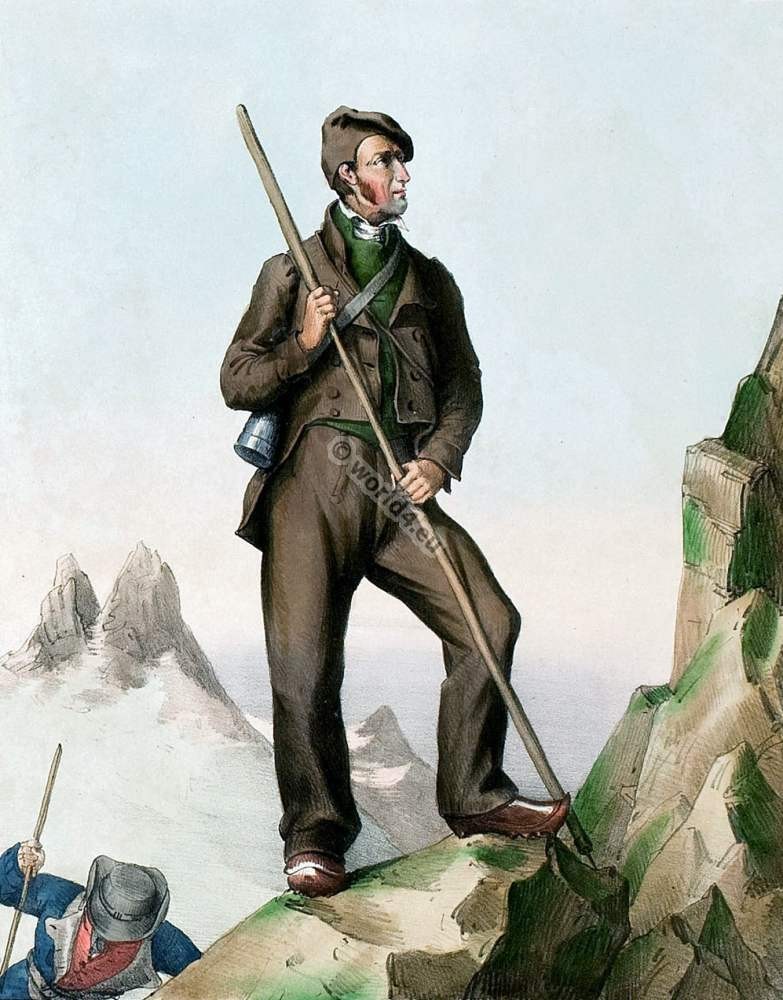

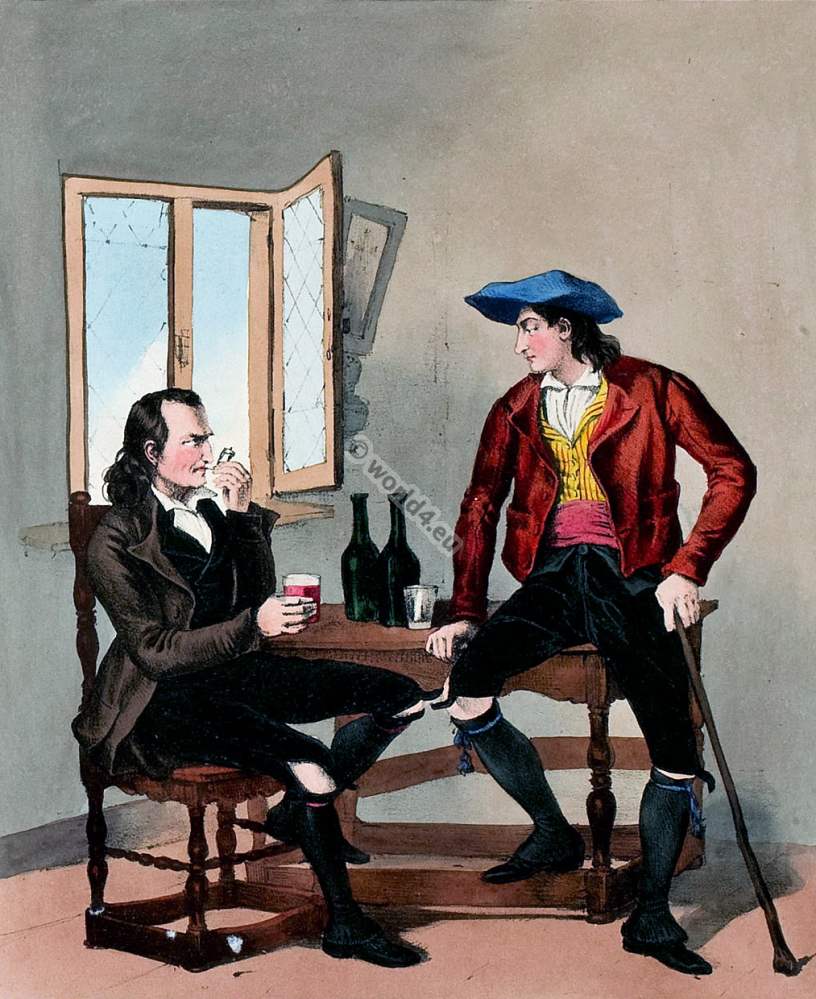

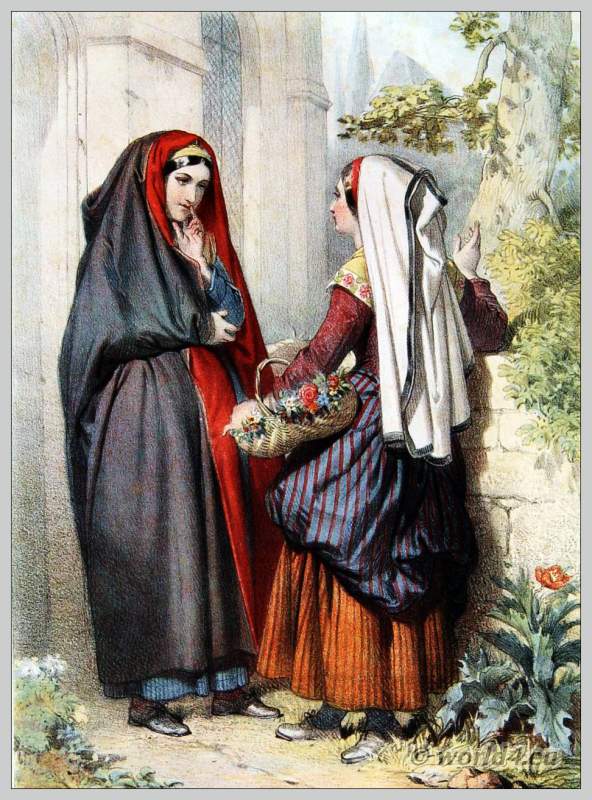

Costumes des Pyrénnées.

Costumes des Pyrénées dessinés d’après nature & lithographiés par Édouard Pingret. Paris: Gihaut frères, 1834.

Traditional French national costumes. Costumes traditionnels français.

by André Varagnac. Assistant curator of the National Museum of Folklore Paris. English translation by Mary Chamot.

An old French proverb says: the habit does not make the monk; the wisdom of our forefathers implied that a man’s clothes can mislead us as to his personality.

While the proverb is true where it concerns individuals, it is false when applied collectively the traditional costume does in fact evoke the past life of the social group which wore it for those who can understand its meaning. I will not go as far as to say that national costumes are equal to the history of a people : an article of clothing is not a page of history.

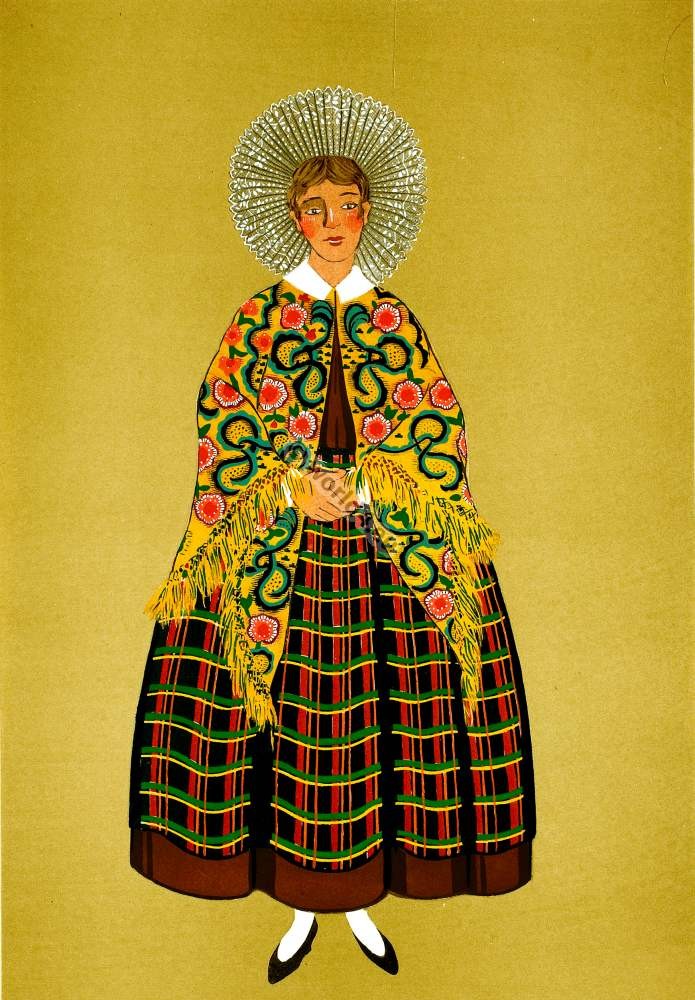

However, look at the Bresse hat (plate 18): this head-gear which was worn by the peasant women on the banks of the Saône as late as the nineteenth century seems incredible, unless we recollect that certain French provinces were included, together with Flanders, in the Spanish Empire. M. Gabriel Jeanton (Gabriel Jeanton (1881-1943), the expert on folklore, has shown us that the Spanish duennas wore this sort of top-knot with black lace. The head-dress was adopted by the rich women of Flanders, passed from there to the Franche-Comté and descended as far as Bresse; it is one of the most picturesque features of the costume which is frequently worn by members of regionalist groups.

Throughout their history the people have collected bit by bit, by hook or by crook, the elements of new costumes. Who among us, does not collect « souvenirs » during our travels? On our return we find our baggage bursting with miscellaneous objects. It is the same with regard to national costumes.—In the course of their long life nations not only surround themselves with but wear on their persons a collection of objects the significance of which they would be unable to explain.

How can we read that strange book, — the traditional dress? As we have already indicated in a previous publication on Central Europe, any traditional dress presents prehistoric features, and aspects inherited from fairly recent history, sometimes even contemporary fashions. Experts know well that such a mixture constitutes folk-lore. But as far as costumes go this duality of origin is more apparent in France than in Central of Eastern Europe. There are two reasons for this which I will try to indicate.

First of all it should be borne in mind that France has always been one of the final points of invasions. Take a map of Europe, or better still, a map of Europe and Asia : the former appears to be a prolongation, or cape projecting from the Asiatic continent towards the Atlantic in the West. At the very end of this immense cape we find the last outpost, a kind of peninsula, which is France. She has served as final buffer to many prehistoric and historic adventures.

Periodically great waves of humanity, coming from the Asiatic steppes, broke against her mountains, covered with forests, or on her western shores where the earth ends and there is nothing but the Atlantic beyond the reefs. They were the people of the steppes, nomads, who rode small, sturdy horses and galloped across the continent. Consult the map again: a vast, limitless plain stretches westward beyond the mountains of the Ural and the buttresses of the Caucasus, Russia, Poland, Germany, Belgium, the provinces of Artois and Picardy, France as far as Paris, the Loire, Poitou and Aquitaine.

It is one of the highways along which formerly countless covered wagons drawn by oxen must have passed, trekking in the fashion of the Boers or Americans trailing westward. As a matter of fact, man did not wait for wheels in order to travel. The European savage living in the wild bush, pushed forward along the banks of big rivers like the Danube, carrying first his flint and later his bronze axes.

Small groups moved from lake to lake, and built dwellings on stacks; others erected enclosures of cyclopean masonry on ridges bounded by two valleys. All these people knew how to spin and weave; they wore clothes. The shape of their cranium is still found among certain types in France to day and, believe me, certain fashions in dress also. Since the end of the Stone Age a number of diverse races have lived side by side in France. Even in prehistoric times they must have been variously clothed. See the diversity in their funeral rites: at certain times in certain regions the dead were buried; at other times or in other parts of the land they were cremated. Archaeologists have sometimes unearthed collective burial grounds, and sometimes individual tombs. It is unbelievable that the people who honored their dead so differently should have been clothed in a uniform fashion; France presents more human contrasts in spite of her present national unity than any country in Europe.

The second reason for the variety of French traditional costumes is of more recent date. We must not forget that the national history of France is one of the longest in Europe. For a considerable time the aristocrat classes, and especially sovereign persons who kept courts, obviously having their own fashions, had constantly influenced the dress of the population by reason of their prestige and the desire of the humble to imitate their betters. Can we explain this action simply by the splendor of Versailles and the Roi Soleil? Things were not so simple until the last few centuries, and it is only in the nineteenth century that France had acquired her present form. Up till then entire provinces were being influenced by other sovereign centers. We must realize how late the centralization of France was accomplished. Not only were important fractions of the French masses influenced by neighboring empires for a long time as I have remarked regarding the Bresse hat; but during all the Middle Ages princes and simple feudal lords kept their own small courts, where the arts and consequently fashions evolved in a particular manner.

With the exception of the mountain and coastal regions where life has always been hard, peasant costume had been too long under aristocratic influence not to have lost most of its archaism. How interesting it would be if a student of folk-lore collaborated with a historian to determine the relative epoch and the probable origin of our regional costume. A new light would be thrown on the currents of civilization in these unknown times, and the curve of a coif, or the pinking of a bonnet would help to discover the old lines of political and economic forces which became so entangled in a Europe giving birth to nationalities.

Everyone knows that the great States might have been differently constituted on the Continent than actually happened. For example the court of Burgundy might have become a royal court with a little intelligence and not much genius. And have we ever studied what ancient Lotharingia meant?* Does anyone remember that a part of the provinces of the Kingdom of France were considered a foreign country up to the Revolution as far as custom duties went, for their having refused to contribute towards the ransom of King Jean le Bon, imprisoned by the English during the Hundred Year’s War? All this evokes the motley of French traditional costume.

- In addition to today’s Lorraine, the Carolingian Lotharingia also included Saarland, Luxembourg, Trier and the areas on the lower reaches of the Moselle, Wallonia, the Lower Rhine with Aachen, Cologne and Duisburg and the south of the Netherlands in the area of Maastricht, Eindhoven, Breda.

Here then, is the infinitely complex canvas which, if we were in a position to recognize and follow each thread separately, would allow us to determine the origin and evolution of every article of these costumes. Shall we attempt this fine dissection? Whole volumes and the patient lives of scholars would hardly suffice. To those who would attempt to follow these researches, I should recommend first of alia study of the treatise of Quicherat (French historian and archaeologist 1814 – 1882.) and especially that of Camille Enlart (1862 – 1927, was a French art historian.) on the history of costume. But such is not the aim of the present volume.

To begin with, the researches that I have mentioned and which will shortly be undertaken under the auspices of the « Musee National des Arts et Traditions Populaires » directed by M. Georges Henri Riviere have been barely sketched so far. Works relating to local costumes are numerous (i) but of varying importance. I may say that books giving scientific descriptions and notably classifications of old types of costumes according to zones are extremely rare as regards the French provinces. Under these conditions, how is it possible ever to fill the lacunae, since the daily wearing of traditional costume has become a memory in most French departments?

Students are generally advised to check the regional revivals by comparing them with nineteenth century descriptions and especially with the numerous lithographs and romantic engravings on one hand, and with old photographs taken before 1900 on the other. This is very excellent advice, but it is only part of the necessary work. Photographs are rarely accurately dated and located, even when they do not deal with figures dressed for an edition of post cards. Usually they only serve to confirm information already acquired.

As to the descriptions by travelers of the last century, these, like the romantic pictures, nearly always lack really scientific precision. The details must be verified one by one from another source of information. Our last hope of achieving more knowledge lies in the old peasant clothes stored away in cupboards and attics. As a result of the many expeditions, especially in Sologne, conducted by him, M. Riviere visualizes the possibility of reaching in another ten years or so, the marvelous source of documentation gathered from systematic inquiries held on the spot by specialists, and of comparing the results of these inquiries with data collected from marriage contracts and from inventories of possessions officially drawn up after death.

Such is the state of our knowledge and ignorance, allowing for a few occasional successes; and we ourselves were determined to envisage these questions only after several years of hard work along the lines already described. But man proposes and God disposes: at times public taste is ahead of the specialist’s work. What miserable artisans we all are, each one in his atelier, where he dreams of an eternity of work before him! M. Lucien Febvre has described this aspect of our life very well. The artisan is a bit of a wizard in his way; but even if he is a master craftsman he can only be an apprentice wizard. There are times when his pot boils over and upsets everything.

And such is the position of folk-lore experts to-day.

The love of tradition is becoming fashionable, and like all fashions is imperious. Fashion is a spoilt child. She wants everything at once. It is then that the good regionalists demur and protest against this fever: they have spent dozens of years collecting the clothes and ornaments of their region. They have had to fight against the false costumes of their locality. They have succeeded in reconstructing the last true costume worn by the peasant women of a certain village, or hamlet. And suddenly fashion arrives from Paris and says: « What a lovely idea for the modiste. This coif will make the sweetest hat for Deauville! »

It is useless crying out or covering our faces at that. Such is life, the life that sweeps like a torrent over our customs. Let science continue her slow march; but she has no right to withhold the result of her researches, however incomplete or rudimentary. Let us have museums, plenty of them, where authentic costumes are pinned together in glass cases like immense butterflies. Meanwhile the street will be full of dresses which vaguely evoke an ancient province, and hats boldly inspired by this or that coif. And these authentic costumes will be imitated, very inaccurately no doubt, in our dance halls, our houses and at our fancy-dress balls.

Our modern life which loves bright colors and secretly hates the banality which threatens our existence, thirsts for fantastic and gay visions which appeal to the imagination of adults as colored albums and Épinal pictures* do to children. It is all a question of measure and common sense. M. Medvey has deliberately omitted to represent the faces and bodies of the peasants in his costumes, and I can only praise him for it. The traditional costume of the French peasantry has become a relic, a relic for science, and it would be impossible to represent it in its natural rural environment, except in a tedious and erudite publication. I wish to tender warm thanks to my excellent collaborator, Madame Germaine Lesecq, whose accurate method and rare devotion enabled us to undertake the difficult and delicate task of preparing the present work. Madame Henri Monceau has furnished valuable documentation for the Bourbonnais costume (Plate 19) and Madame Felix Chevrier has kindly helped us for Lorraine (Plate 11). I also wish to thank Madame Laperrière who explained certain details of the Savoyard costume. I hope that all these will find here the expression of my sincere gratitude.

- Picture sheets are the single-page prints (flat print) of the 18./19. Century, most of which were handcoloured. As popular picture and later reading, they were widely used. Jean-Charles Pellerin — having been born in Épinal, named the printing house he founded in 1796, Imagerie d’Épinal.

These delicately colored pages about to be scattered far from the lands where the archaic clothes, which served as distant models for them are stored, now faded and smelling of lavender, can and must be the means of acquainting us with the soil and of teaching us to know and love it better. One cannot attempt this without trying to represent, however sketchily, their lineage.

Let us take these pictures in one hand and a bundle of slips in the other. Life hurries on. Well, let it then receive the testimony of a science in the making, in the lack of a science already established. Let it follow us into the wings, into the ateliers where ideas are being ceaselessly cut out, beaten, forged and clipped in an endless attempt to adjust them to life, which escapes and never stands still. Though we are not yet in a position to present a «natural history of French peasant costumes», we have advanced far enough in historical research, thanks to M. Camille Enlart, to outline broadly the evolution of the principal articles of clothing of our regional costumes for men and women and their many variations.

As I have already remarked, I expect a great deal from the comparison of the traditional and the prehistoric costume. No sooner do we leave the highways with their fast cars, than life in the country forcibly reminds us of the true rhythm of History. When you stop for a minute on the landes of the Limousine the silence provokes a singing in the ears of the town-dweller. The surrounding country seems to be absolutely deserted save for the distant figure of a farm-hand guiding a couple of oxen harnessed to a wheelless wooden plough, which resembles in many points the swing-plough of Roman colonists. Occasionally the man speaks or sings to the beasts in harsh or soft tones, which carry surprisingly far. In the middle of the landscape under a chestnut tree stands a dolmen like a budding cathedral rising from the ground. For twenty, twenty-five, thirty centuries and maybe longer, the picture has been the same; probably the lande had more grass, was more steppe-like and the gorse was thicker. And what about the men? Did they wear skins? Or tunics, which we consider feminine? Were they draped like the Romans or like the present-day Hindu?

Everything tends to prove that the Gaulish peasant wore trousers and clogs like the twentieth century French peasant. It is precisely in the male costume that the prehistoric element is more easily found. In spite of the rather tight-fitting breeches that court fashions frequently imported for festive and ceremonial dress, many of the male costumes have either straight trousers or pleated and puffed ones called Bragou-braz in Breton. Both go back to prehistoric ages. Have you ever looked at ancient monuments of Parthian or other «barbarian» warriors? If you take into account the technique of gathering pleats — inevitable to artists who themselves wore draperies, we have here on these reliefs and on the pottery the prototype of our modern trousers.

M. Marcel Mauss has pointed out that the garments with sleeves and leggings which differ so much from the ample folds of draperies, commemorated for us in Greek statuary, appear to be one of the characteristics of subarctic or steppe civilizations. We must bear in mind the waves of migrations: they start off from a vaguely defined domain in Central Asia or Eastern Europe, to descend on one hand towards France and Spain, and on the other hand, towards the near East, Iran and India. These men were horsemen wearing trousers and leggings as opposed to the Roman cavalry. The Legions encountered them at the two ends of the world as it was then known: in the Near East it was the Parthian cavalry that Rome never got the better of; in the West it was the cavalry of Vercingetorix, and later that of the Germanic tribes, which the Emperors hired as auxiliary contingents. The comfort of the dress was so obvious that the short breeches (femoralia) became more and more customary in the time of Augustus. They resembled our shorts. Later on, at the time of the Byzantine Empire, Rome adopted the long Gaulish braies or trousers. That is how Alexander Severus came to wear long white trousers.

It would therefore be wrong to think that the wearing of trousers was adopted in the country by French nineteenth century fashions. Certainly the old rural costume often included breeches, in imitation of the town-dweller of the eighteenth century, — breeches ending in gaiters. But trousers were not totally ignored by the country people. In fact we can assert that modern dress owes this garment to popular tradition, which is conservative in spite of the caprices of aristocratic fashions. The Francs strengthened this tradition which had been rather compromised by the customs of rich Gauls, who were Roman citizens.

Chessmen dating from the time of Charlemagne clearly show us the dress of the Frankish troops: the horsemen wore leggings over their breeches. It is certainly very difficult to reconstruct the successive types of clothing during the Dark and Middle Ages. Yet it would seem that long and straight trousers were chiefly kept as the traditional costume of seafaring men, while the peasants and artisans appear, in the rare pictures where they are represented, to be dressed like our boy scouts or attired in wider pleated and puffed breeches, not unlike those worn by the Zouaves, or the bragou-braz of the Bretons. And it is among the sailors that the French Revolution was to rediscover the classical shape of the long trousers, which were to become the distinctive mark of the « patriots », the «sansculotte»; as opposed to the «aristocrats» in stockings and buckled shoes. Ever since then the riding boot has given way to trousers strapped under the foot which became one of the principal elements of romantic elegance.

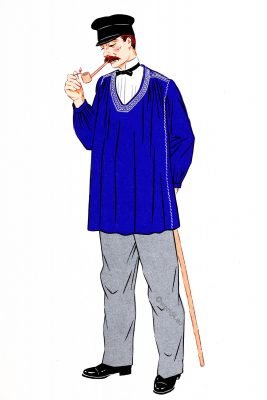

Another immemorial article of the traditional male costume is surely the blouse. Certain Parisian trades still wear it — the market gardeners; while the masons, delivery boys, street porters etc. gave it up quite recently. The great increase of knitwear and leather during the Great War and as a result of sport is one of the principal causes for the disappearance of the short and pleated blouse in the city trades and consequently in its actual uses in the country. The blouse is a vestige of an antique costume in that it is an outer linen garment. It takes us straight back to Merovingian times. Let us consult a reproduction of one of the rare contemporary documents representing figures. We find that the men are dressed in two shirts. The one underneath was called subucula* and corresponded to our modern shirt; the one on top was called dalmatic and was simply a blouse with looses sleeves which reached to the knees, whereas our country blouses stop mid-way down the thighs. The Gallo-Romans of the sixth century wore a cloak, with or without a hood over this blouse. The Francs wore the Gaulish woolen sate instead of a cloak, or a heavier fur cloak. The shirt, blouse and cloak were retained indefinitely by shepherds and herdsmen.

- The subucula is the lower of the two tunics (Tunica intima).

But let us return to the long tunics of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries of which the Catholic sacerdotal vestments are a memory. Towards the middle of the fourteenth century the male tunics start suddenly to grow shorter, barely reaching to the waist. The hose become unusually developed, rising as high as this new short tunic. The light breeches worn by the nobles and bourgeois of the Middle Ages are really an ordinary pair of leggings, fitting tightly, and they end by uniting into a single garment fastened at the waist. The breeches (our shorts) which covered the hose became superfluous and only remained as accessories called trunk hose, while the rest of hose became the stocking (has de chausse, from whence has, stocking, a word still used in French).

I have already mentioned the curious insistence on the double tunic, inherited from antiquity, in Central European countries. Thanks to the researches of historians we can see through successive centuries the evolution of aristocratic dress which influenced the peasant fashions in France. It was probably in imitation of the fashions of the Byzantine Empire, the spiritual and economic supremacy of which extended far to the West, that the double tunics of the men’s costumes were lengthened during the early Middle Ages so as to trail on the ground. It becomes difficult at this time to distinguish the dress of the two sexes. The elongated silhouettes which adorn the portals of the Cathedral of Chartres and many other Romanesque churches present a singular appearance not unlike the pipes of an organ. It was the linen shirt (chainse) covered by the long narrow tunic (bliaud). The people at that time wore either relatively short knee length blouses or tunics; which were sometimes tucked up or gathered under belts. This tucking up of the hems, which must have been rather uncomfortable, persisted among the habits of the country people. In the fifteenth century the Tres Riches Heures of the Duke Jean de Berri shows us mowers and haymakers attired in this fashion. During the eighteenth century this tucking up of women’s skirts was very current: that was how (more than by the use of rush bustles or padding) the countrywomen imitated the «paniers» of aristocratic gowns. The bad state of country roads up to the nineteenth century obliged the peasant women to tuck up their skirts almost always.

From the thirteenth century, and very clearly in the fourteenth, clothes became more complicated and articles of clothing appear which we find in the traditional costumes as well as in modern dress. Each of the two tunics is again doubled: and we find the shirt is covered by a doublet, the ancestor of our waistcoat. At the same time the outer clothes (the bliaud, the ancient dalmatic) is divided into coat and sur-coat, the ancestors of our jacket and overcoat respectively. In the fourteenth century most of these articles of clothing were close-fitting, which distinguishes them from the dress of the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Therefore it is during the fourteenth century that the close-fitting elements of traditional costume originated (we must not forget that nothing remains of the loose tunics but the blouse or the cape). And here it is that the practice of padding, which we find in so many regional feminine costumes, starts. During the Middle Ages knitwear was unknown (knitted hose began to be mentioned in the fifteenth century). The use of knitwear for underclothes is quite modern. Lacking jerseys, our ancestors used padded linings between two layers of quilted linen. This technique was very important in determining the silhouette: padding allows for aesthetic deformation, and helps to find a fashion of « line ».

We have already recalled the « paniers » of the dresses during the Old Regime. It was only the end of a long tradition, the first excesses having appeared in the fourteenth century, especially at the court of Isabeau of Bavaria. At that time women affected a waddle. Even their hair was padded, and rose in fabulous hennins: the high coifs of Normandy and Saintonge have kept the memory alive. As to the dresses, they became corsets, that is to say short, slashed in the bodices, and laced. During the winter the corset was lined with fur. It introduced in the country the wearing of close fitting dresses in such heavy material, that they supported the torso without whalebones. And so it is that the body of woman since the fourteenth century up to the traditional costumes of our regions, has been stiffly trussed. In the case of the Savoyard costume the local aesthetic demands a square torso « the clock case ».

Many important changes dare from this period. The neckerchief was one of the most charming features of eigteenth century fashions and some of our regional bodices seem to have imitated this fashion of Marie-Antoinette’s court: certainly it helped enormously to popularize the shawl, but the scarf had existed since the fourteenth century; Enlart explains that it had originally been a traveling-bag, but had become a strip of material worn over both shoulders or across one (Le Costume, Paris, Picard, 1916, p. 94.).

Therefore, we cannot exaggerate the important influence that aristocratic fashions in the fourteenth century exercised on the ulterior evolution of traditional dress. M. Marcel Mauss often stresses the deep impression made by the coming of Isabeau of Bavaria and her court; for the first time a taste for luxury was implanted in French mediaeval society.

The peasants came in to this heritage during the following centuries and made but few subsequent changes in their dress until the nineteenth century, when the invasion of readymade clothes reached even French villages. When feminine dress was divided into bodice (caraco) and skirt and certain masculine festive clothes included the culotte à la Français and the three-cornered hat, the chief variations of the traditional costume since the Hundred Years’ War had taken place. The rest is a question of local evolution, of conservatism or imitation peculiar to certain regions, villages or even parishes.

We have still to consider the influence of the romantic age on this series of evolutions. But here the study of costume was impeded by a controversy on quite another subject. Students of folk-lore began by studying legends, tales and superstitious beliefs instead of popular life. Eminent nineteenth century sociologists applied themselves to discover links between these traditions and the pagan religions of antiquity. The scent was hot, and the hunt was successful. Perhaps too successful. There was a time when every thing, from the use of the umbrella to the growing of pumpkins, was explained by solar myths; so in folk-lore everything was due to pagan cults. The reaction was inevitable.

There are admirable souls who inform you that Carnival, which is dying out in our villages was perhaps imported from Italy through Nice during the Second Empire. The same story holds for dress. We are told that the authors of romantic lithographs might very well have not only invented their so-called documents but even created local fashions by their fantastic pictures. Briefly the scientists and the artists of a hundred or hundred and thirty years ago were unduly interested in « local color », and added it where there had been little before. Carried away by their desire to admire the picturesque, they may even have suggested to local tailors and embroiderers how to enhance their models and have furnished them with designs for the embroidering of some of the Breton costumes.

I admit that I am not convinced, or rather that I believe such influences had always existed without really achieving the effect attributed to them in the circumstances. I do not conclude from the fact that some of the present day Breton pottery is quite unlike that of seventy-five years ago, that the romantic artists must have influenced Breton dress fashions during the past century. We know that the contemporary pottery comes from important factories founded at the end of the nineteenth century. It had little in common with the older crafts, though it has its own merits. And it cannot be compared to the conditions in which the local tailor worked and often still works, when he has not been ousted by the competition of mass production suits.

To conclude, we find that in the majority of cases our first documents concerning the dress of this or that region go back to the romantic age, and that during the preceding centuries painters, engravers, sculptors or draughtsmen represented the common people clothed in a uniform of poverty, if not in truculent rags. From this very true statement we come to the singular conclusion that peasant dress up to the romantic age was very alike everywhere, and varied but slightly from century to century, reflecting the distant fashions of court. By creating the Office of Folk-lore Documentation at the Palais Chaillot, and by enriching it daily, M. Rivière methodically collects all the material bearing upon this question. Is it too soon to venture an opinion? I do not think so. Already serious local enquiries, of which M. Gabriel Jeanton has furnished an example, have helped to discover the existence of very special regional fashions long before the romantic period.

The relative uniformity of popular dress in documents earlier than the nineteenth century simply shows us what has often been noted in other artistic spheres: from the seventeenth century onwards artists are not really interested in the people except on rare occasions.

Those among them who continued the admirable tradition of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries and were not guided by convention, those « painters of reality » who are being patiently discovered by M. Rene Huyghe, have nearly all, with the exception of lye Nain, been forgotten. How many canvases of the eighteenth century represent stereotyped cottages, which give us at the most an idea of the artist’s origin or of the part of France that he knew best! Why is it that we have no conventional farmers, tradespeople, peasants? Were they not at least part of the background?

I deemed it necessary to stop at these arguments for we had already collected bit by bit a certain amount of information regarding the great age of traditional dress. It is always worth while to submit a bona fide objector to an objective examination. What we finally deduce from the contemporary tendency to « rejuvenate » the traditional costume is the general fact that in the nineteenth century, which was to witness their almost complete disappearance, the different regional costumes tended to vary and to change more rapidly. It was like a dying person’s fever. This is quite comprehensible and I am willing to concede this point to the partisans of the romantic origin of our regional fashions, though I do not explain it in the same way. I cannot suppose that the cause of this rapid evolution of our peasant fashions was due to any propaganda of the intellectuals. I simply consider that the nineteenth century was the age which metalled country roads, built railways and eventually produced the motor-car. Individual contact between countrymen and the big centres increased so much as to become a mass phenomena, men and goods travelled more easily. And the small centre of civilization which harbored the local tailor and his clients now received more and more manufactured articles from outside : another thing to upset the tailor’s trade is the fashion-plate, which is beginning to find its way from town to town, and soon from borough to borough. And it will not be long before fashion magazines penetrate as far as our villages. The tailor’s trade declines as a result, before dying out completely.

But these controversies would perhaps not arise if anyone knew more about the tailor’s singular trade: it is time to evoke it if we want to surround our pictures of peasant costumes with their picturesque social background.

Few people know that there used to be such disgraceful trades, that only the feeble, the sick or the puny could follow them. In Africa it is often the blacksmith who loses caste. In France it used to be the tailors and the rope-makers. An excellent chronicler of life in Brittany a hundred and thirty years ago, O. Perrin, records the helotism of these artisans in Armorican * society and tells us that « the tailor endeavors by every means to attain a different position to that which he is entitled to by his profession. The contempt with which he is treated by our peasant nobility, e. g. the laborer, no doubt dates from the far-off times when industry, now a reigning queen, or any other sedentary occupation was considered an infamy. At that time only those who could not work in the fields or fight followed such an occupation. Therefore tailors were generally poor creatures disgraced by Nature, hunchbacks, one-eyed, lame, all the misshapen and incomplete male population of the villages. It was natural that their physical inferiority and their feminine trades placed them on the lowest rung of the social scale in the rough fighting days; only the rope-makers, cacoux, that other caste of pariahs, were below them ». (Galerie bretonne, 2nd edition, Paris, 1838, vol. III, pp. 26-27.)

- Aremorica (also Armorica, from Celtic are mori, “in front of the sea”) was a geographic name for the north-western coast of today’s France between the rivers Sequana (Seine) and Liger (Loire), today’s landscapes Normandy and Brittany.

It is possible that Perrin, who published his work in 1808, rather exaggerated the lot of the unfortunate tailor. Popular tales represent this artisan as a jolly little fellow, shrewd and industrious, like most dwarfs, all the more amusing because they are not important. No sooner was the wool spun, and the cloth woven by the village weaver, than the tailor was expected ; he always settled down in the farmhouse for several weeks to enable him to clothe the whole family. Though he was constantly on the move he rarely travelled far. He had his own circle of clients and never saw as much of the world as the stone-cutter or the itinerant tinker. Such was the master of local elegance, and we must try to imagine him in order to understand how so many strange costumes evolved. He conscientiously followed the old rules of his trade which he had been taught, allowing himself an occasional innovation: it was his way of doing his best. His clients, like himself were swayed by two desires with regard to dress- fashions; one was to conform to costume for the honor and prestige of their little community in competition with neighboring villages, and the other to imitate after a fashion the marvellous attire worn by the bourgeois or the nobility, who sometimes visited their lands between two sojourns at court. Poor, touching, fearsome imitations, artless and naive, for the peasant had no right to wear the dress of the great.

The originality of folk-lore is found in just this mingling or rather in this incessant and candid juxtaposition. With his amazing hereditary ability the local tailor created new fashions with bits and pieces naively added to his stock of regional tradition.

The portrait of the tailor, who is rapidly becoming a legendary figure would be incomplete if we did not mention the social significance of his functions in the heart of these small communities. There has never been one type of traditional costume only in the same village at a given time: these costumes have always varied, not only according to, sex but also according to age and wealth, which is the real basis of social condition among the peasantry.

Charles-Brun tells us the following about feminine dress in the valleys of the Pyrenees: « The colors or details of feminine costume in the valley of the Ossau are significant. The widow is always dressed in black. Married women between the ages of twenty-five and thirty-eight wear a black hood or cap. The young girl has a white pinafore, the young married woman a black one. An heiress wears the same red skirt as other girls, but adds a broad green silk ribbon »(1). Such peculiarities of dress have been described for other regions. They would appear everywhere if the studies of traditional costume had been carefully conducted before the decadence of these costumes. In Bresse, and especially in the charming borough of Romenay, where the new Museum of Folk-lore obtained one of the prizes at the International Exhibition of 1937, young girls of marriageable age wear lace bonnets with more or less lace frills, according to the amount of their dowry (2) and a red ribbon under their chin to distinguish them from the ordinary girls.

So it was that the tailor was intimately connected with village life; he created for each person what was in reality the emblem or living advertisement of that person’s real condition. It is therefore hardly surprising that the tailor was traditionally chosen as go between during betrothals? Perrin gives us a humorous description of him (3), as well as of the extraordinary luxury of the three costumes which the bride had to wear successively.

This last trait helps us to place the man at a time when the traditional costume was part of the family wealth. A part of the reserve was worn on one’s back in the form of precious metal. The tailor deposited certain family possessions in embroideries and gold lace; he invested them in ornaments much as a solicitor invests money in bonds.

Referring to the costumes of Central Europe we have noted the ancient function of this marvelous use of ornament. I am inclined to believe that the accumulation of metal ornaments is not a recent phenomena, but rather the contrary. The increase of trumpery finery during the nineteenth century was no novelty, but expressed primitive desires; it occurred whenever highly colored industrial materials arrived on the local market. The adopting of certain colors in the traditional costume remains a sign of archaism even if it merely concerns ordinary aniline dyes.

And now we must justify our choice from among the regional costumes. Modern taste inclines towards old predilections. The need to evoke gay images and bright colours turns us towards the most archaistic parts of the country. From Brittany to Alsace, and to the Basque country we have concentrated chiefly upon the mountainous regions and the coast where the oldest folk-lore is to be found. Several plates, often reproduced from older models, furnish terms of comparison with other regions, where interchanges since the preceding centuries were so frequent, and where the traditional costume varies but little from the town fashions of old.

Foreign readers to whom the contemporary aspect of France is unfamiliar, must not think that a journey across our country would put them in the presence of traditional costumes. Some day, perhaps, the girls from our provinces will understand how much of their charm they lose in adopting the banal uniformity of the « latest thing ». Charles-Brun, the apostle of triumphant regionalism may count on the trump card which is feminine vanity. The day that our country girls will make up their minds to sew their own festival clothes their ingenuity will be comparable to that which inspired the late village tailor and that day the regional costume will have regained its place in the heart of popular art and living folk-lore.

André Varagnac (1894-1983)

Tip: In these days, if one wants to sew their own festive costumes or want to add ancient cultural features to their modern designs, they can make use of custom patches that can be freely designed.

(1) Costumes des provinces françaises, Paris, Ducher, n. d., vol. I, p. 38.

(2) See Gabriel Jeanton: Costumes bressans et mâconnais. Tournus, Renaudier, 1937, p. 31

(3) Ibid. p. 25 ff. The tailor as ambassador.