ABBOTSFORD.

"I passed by the halls of Balclutha,

And behold they were desolate."

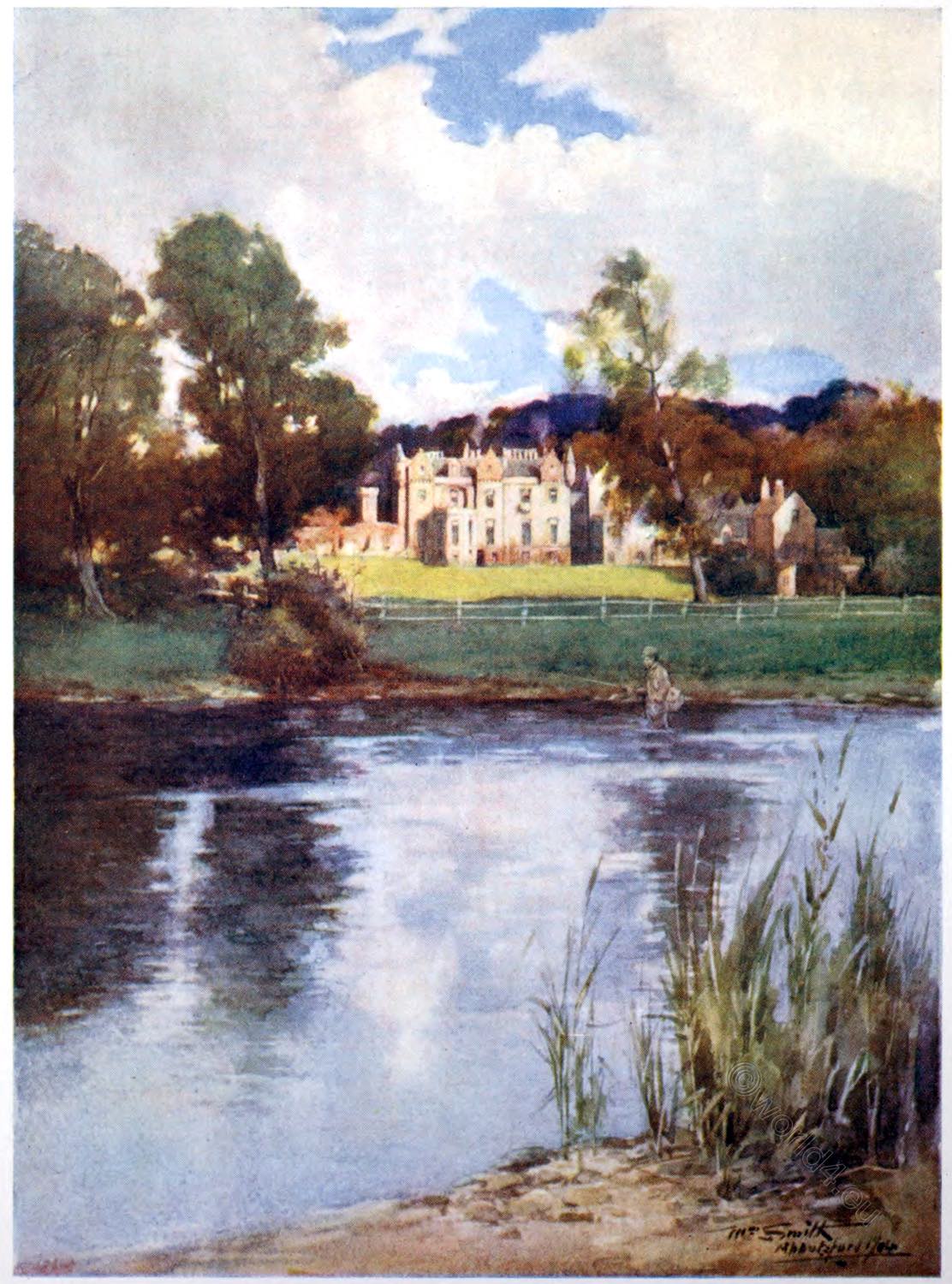

Abbotsford, the well known mansion and estate of Sir Walter Scott, is beautifully situated on the banks of the Tweed, amidst the most enchanting scenery. Seen from a distance the appearance of the house is most magnificent, and as Sir Walter was wont to say— “a romance in stone and lime, one of my own palaces reduced to reality.”

Without belonging to any style of architecture, it partakes largely of the gothic, and combines most of the characteristic features of the old baronial halls. A huge gateway leads into the court-yard, to which are attached a pair of iron collars, formerly used for confining criminals by the neck.

The building is of blue whin-stone, faced with sandstone doorways, windows, cornices, and ornaments, the colours of which contrast finely in its projecting balconies and castellated turrets. The court-yard forms a large square before the house; directly opposite the gateway is a gothic screen of open arches filled with a network of iron, displaying a charming prospect of garden ground behind—beautifully laid out in the old formal style.

Old tablets, rude carvings, monumental remains, antiquities gathered from castles, abbeys, churches, and palaces, attract the eye at every turn, and bear evidence to the devoted enthusiasm and laborious exertion which the noble author brought to bear on the decoration of his mansion; and as several of these ornamental sculptures were the gifts of friends, they bear pleasing testimony to the warm affection with which his friendship was regarded.

Perhaps the most curious relic is the door which formerly closed the portals of the old Tolbooth, Edinburgh: it is built in about half-way up the wall, and at the west end of the house there is a doorway composed of old Tolbooth stones. These were given to Sir Walter when the building was pulled down in 1817.

Not far distant from the doorway is Ralph Erskine’s pulpit—one of the writers of the ” Explanation to the Assembly’s Catechism,” and a justly celebrated divine of the Kirk. All around the back of the house and along the wall of the garden there is a balcony of cast metal—a present from his publishers—and also a finely trellised shaded walk; while at the front is the stone fountain which formerly stood at the old Cross, Edinburgh.

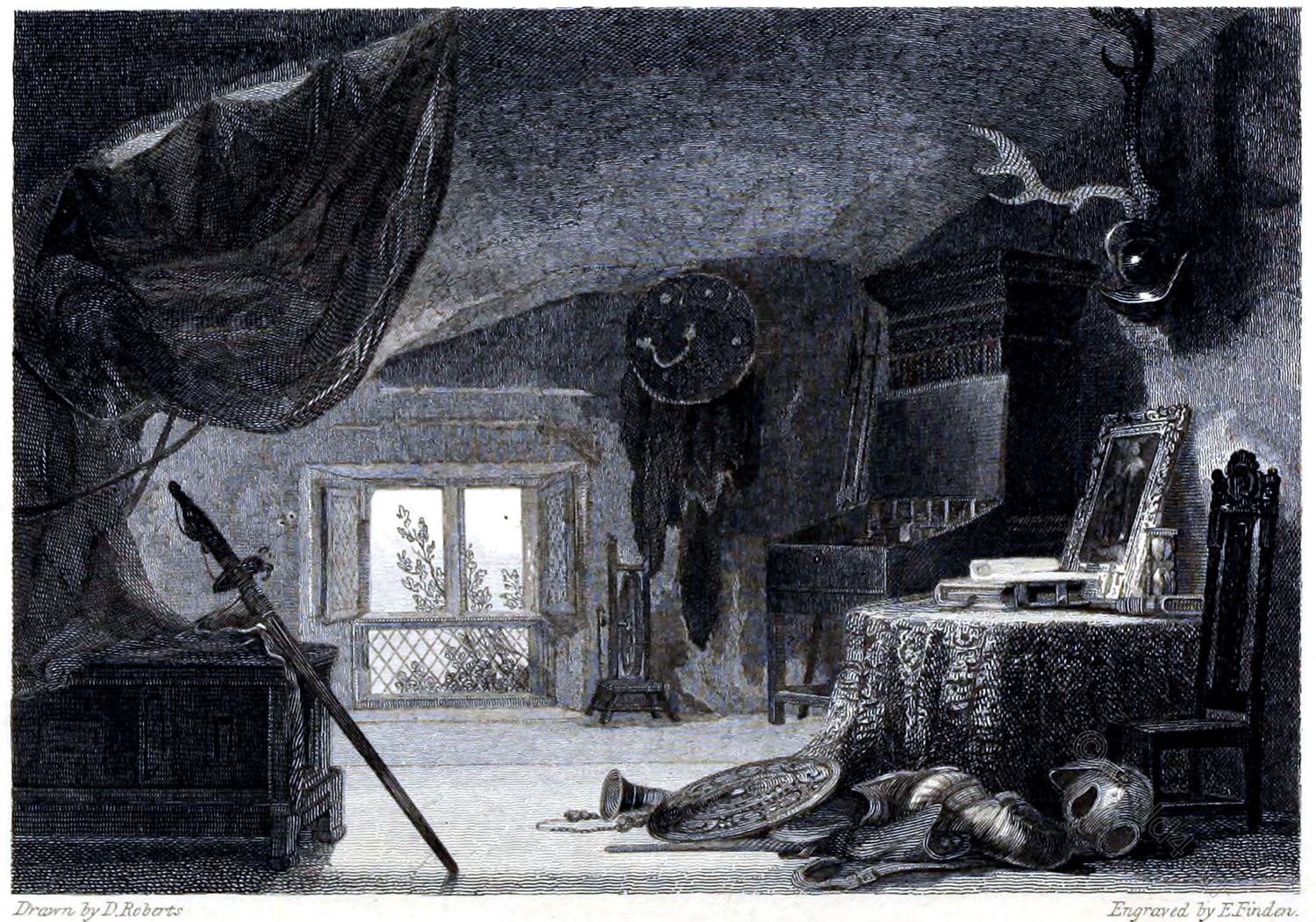

The chief entrance to the mansion is a copy of the porch of Linlithgow Palace. Under its roof is a pair of wild bulls’ horns, and over the door is a pair of elk antlers. The door leads the visitor directly into a large, handsome baronial hall, decorated with emblems of chivalry, and containing some highly interesting and valuable antiquities.

One of the “hawls” to which Sir Walter alludes in his letters, was the richly carved old wainscot on the Avails, and which he obtained from the Palace of Dunfermline. The floor is of black and white marble, the roof appropriately embellished with armorial bearings. Two rows of escutcheons run along the cornices of the ceilings, emblazoned with the heraldic distinctions of those who kept the borders.

The fire-place is a copy from Melrose Abbey. In the corner near the door are the keys of the Old Tolbooth, while every part of the room bears some interesting relic of bygone times, many of them associated with the poems and novels of Sir Walter.

Scott’s Library is a good sized room, shelved from top to bottom, and containing an immense collection of reference books. In the centre is a plain, narrow table, and a leather chair. A narrow gallery runs round the room, affording access to the higher shelves, and communicating with a bed-room.

In a closet attached to the Study, are to be seen the costumes Scott wore as a member of the Celtic Society and of the Yeomanry Club, and also his last country dress, the broad skirted coat with large buttons, the plaid trousers, the heavy shoes, and stout walking stick—the dress in which he rambled about in the morning, and which he last wore alive.

The Study communicates with the Library; this room is splendidly fitted up with all that taste could suggest or wealth purchase. The ceiling is of carved oak, after models from Roslin, and the balconied windows look out upon the Tweed. Over the mantle-piece is a full-sized portrait of the poet’s eldest son, in the Hussar uniform. At one end of the room is the magnificent bust of Sir Walter by Chantry, and at the other a copy of the Stratford bust of Shakespeare.

The Library is connected with the Drawing-room, containing portraits of Sir Walter himself, of Mrs. Scott and her daughters, and also of Mr. Lockhart. In this room are a set of richly carved ebony chairs, presented to the baronet by George IV.

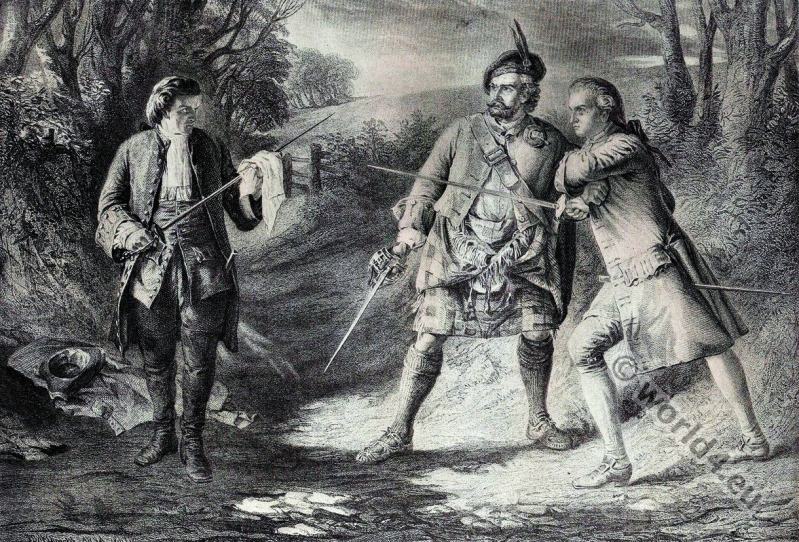

Adjoining the drawing-room is the Armoury, a narrow room of considerable length, with an arched roof, and a blazoned window at either end. Amongst other curiosities this room contains the pistol of Claverhouse, the sword given by Charles I. to Montrose, Rob Roy’s musket, Hofer’s blunderbuss, the hunting flask of James VI., the pistols of Napoleon, &c.

The Armoury communicates with the Dining-room, containing portraits of Cromwell, Claverhouse, Lord Essex, Charles II, Charles XI of Sweden, and a head of Mary Queen of Scots in a charger. This room communicates with a small parlour, in which is preserved a most valuable collection of paintings.

There are few places of more interest to the tourist than the palatial residence of Walter Scott. It was the ambition of his life to build up a baronial mansion, and to restore something of old baronial state, and “here he gradually raised, as his resources increased, the magnificent structure, which stands unequalled in either Scotland or England.”

In a sketch of Scott’s life, appended to an edition of the poem, the editor remarks with some severity on the “reckless ambition to be the founder a house, the creator of an estate and title,” which “marred the fair proportions of his mind, neutralised his natural generosity, and drowned his heroic spirit in the cold waters of selfishness.” But these remarks are neither gracious nor candid.

Scott’s was no vulgar ambition; it was grafted on the ardent feeling for blood and kindred which was the great redeeming element in the social life of what we call the Middle Ages. His yearning desire to make an era in his family was something better than the common-place object of amassing a fortune and investing it in land.” ” The lordliest vision of acres would have had little charm for him, unless they were situated on Ettrick or Yarrow.

His enthusiasm for Scottish antiquity was seen in every part of his splendid mansion, “every roof and window blazoned with clan bearings or the lion rampant gules, or the heads of the ancient Stuart Kings”— he wished to revive departed glories—and this and no more was the innocent ambition of the lord of Abbotsford.

Source:

- Album of Scottish Scenery: a Series of Views, Illustrating Several Places of Interest Mentioned in Sir W. Scott’s Poems and Novels by John Tillotson London: T. J. Allman, 1860.

- Abbotsford, painted by William Smith, jr., described by William Shillinglaw Crockett (1866-1945). London: Adam and Charles Black, 1905.

Continuing

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.