CENTRAL ASIAN RUGS BY MAJOR HARTLEY CLARK.

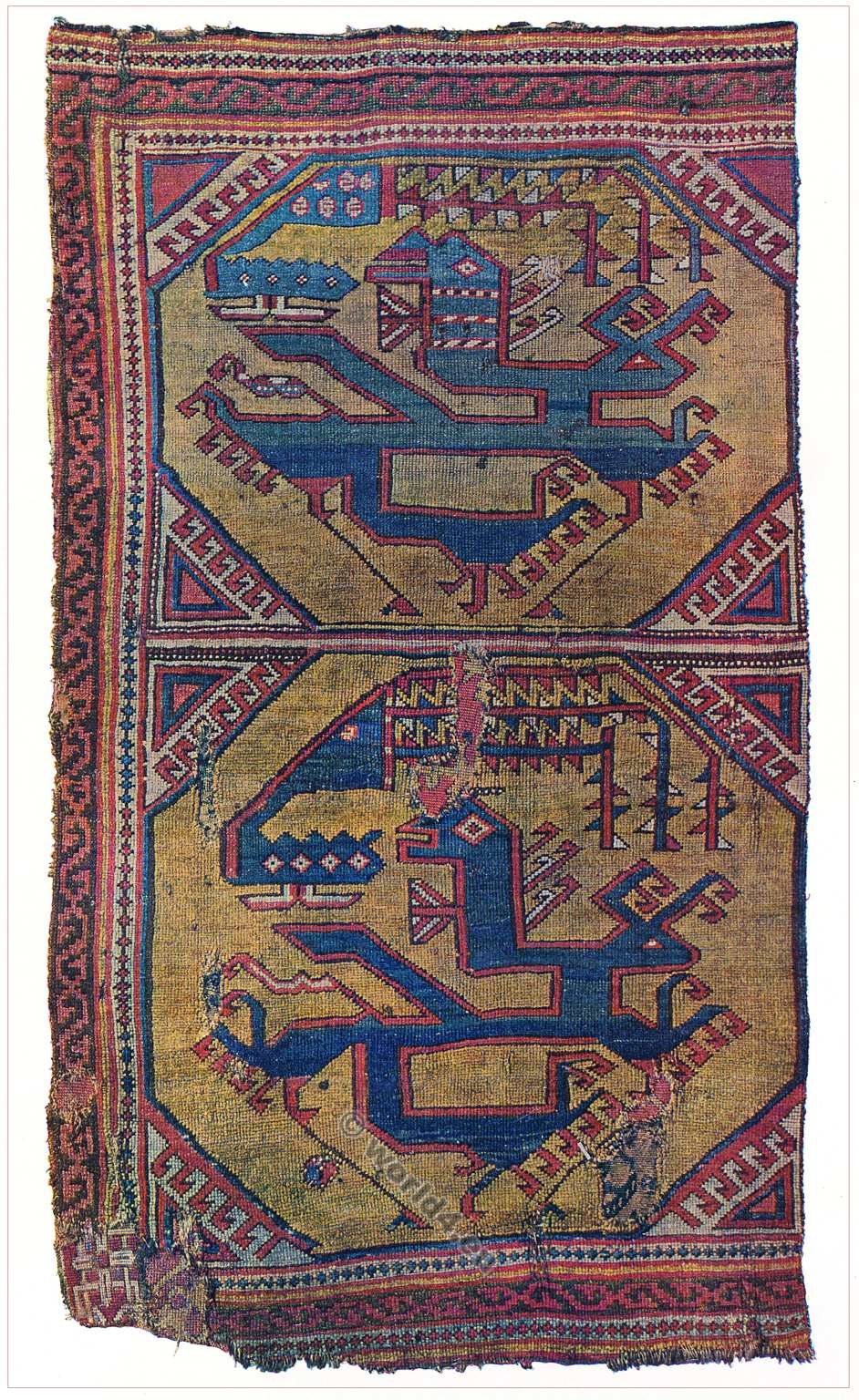

An Adraskand Carpet.

The carpets of Afghanistan, apart from those of the Afghan Turkomans, are, together with those of Baluchistan, in a group by themselves, and in dealing with this group of rugs there are several stumbling-blocks of nomenclature to confuse the uninitiated.

Firstly, the class of carpet most generally called “Afghan,” at the present time, is the Afghan Turkoman, or Filpa.

Secondly, this group of rugs, the majority of which is woven in the country south of Herat, in the province of that name, as far cast as Kandahar, and as far south as Baluchistan, is often quite properly referred to as “Herati.”

Thirdly, it must be realized that this quite appropriate name, “Herati,” is apt to confound the unwary, in so far as these rugs bear neither resemblance nor relationship to the ancient Herati rugs with the well-known design of that name. The latter are purely Persian in every characteristic, being indeed woven by Persians in Herat at the time when that city was a part of the Persian Empire, and later being made actually in the Persian province of Khorassan. Similarly the so-called “Kabul” rugs were woven entirely by Persian artisans at Kabul in years gone bv, and were not in any sense an Afghan product, though bearing an Afghan name.

Fourthly, to make confusion worse confounded, this type of rug is, both in the east and in the west, frequently called “Turkomani,” whereas, strictly speaking, it is not Turkoman at all, though there are several points of kinship between the two groups.

Fifthly, there is amongst Eastern dealers a sort of generic term for all the several varieties of the group. This term is “Siyah-kar,” which which means “dark work,” and refers to their general coloring, which is usually very sombre and gloomy-dark blues, dull reds, and browns predominating.

The finest carpets of this type are those made in the Adraskand valley, which is a narrow gorge running roughly east and west, about forty miles south of the city of Herat. These carpets are not infrequently less sombre than the other subdivisions.

Another subdivision is known as “Sabzwar,” being woven in the province of that name south of Herat. Here, again, a minor confusion is introduced by the fact that the word “Sabzwar” means “green colored,” and, consequently, native dealers often wrongly group together and classify as Sabzwar all such carpets as contain a considerable quantity of dark green. Of these there is a fair proportion.

There are further subdivisions gradually merging into the Baluchistan proper, which is a similar type.

The characteristic field patterns of these rugs may roughly be divided into two main categories – (a) those containing large geometric figures, ill-defined octagons, and crude “Trees of Life”; (b) those containing a regular repetitive design throughout the field, such as a diamond or eight-petalled rosette formation, generally profusely surrounded by latch-hooks.

The main border is commonly of a rectilinear floral nature, the edges of the design being frequently picked out in white. This is flanked on either side by secondary borders of formal geometric design, whilst the guard stripes are often the “running latch-hook” or the so-called “reciprocal trefoil.” These border designs, together with the very common use of the latch-hook and of the octagonal disc in the field, are curiously Caucasian in feeling.

The prayer rugs of this group have rectangular mihrabs, which are frequently much deeper than they are wide, and sometimes contain an octagonal plaque, on to which the devout Mussulman bows his forehead in prayer. The field of the prayer rugs usually consists of a small repetitive leaf design or a “Tree of Life ” formation. It is not uncommon to find prayer rugs, and sometimes other small rugs, which depart in color-scheme from the usual sombre tones to the extent of employing a natural camel-hair or fawn color in the field. This is a not unwelcome relief from the customary dull reds and deep blues toning to purple, together with an often extensive use of dark green or brown.

The carpet illustrated is an exceptionally beautiful fabric from the Adraskand valley, dating back to the eighteenth century. Of unusual size, exquisite workmanship, and skillfully drawn design in a wealth of color seldom met with in these rugs, it was obviously made to the special order of some wealthy potentate, probably as a Durbar carpet.

A field of deep translucent blue, edged round with a large running latch-hook, is the background for an all-over repetitive design of eight-petalled rosettes within diamond formations, each surrounded by small latch- hooks, the color-scheme of which is in varied shades of red, blue, saffron, and flame color. Good as the plate is, it has failed on this small scale to reproduce adequately the beauty of the chromatics.

It will be noticed that rather than have any incomplete portions of this repetitive design at the edges of the field, the spaces have instead been filled in, according to the weaver’s fancy, with a number of small devices, amongst which are included conventional floral designs and small octagonal discs containing eight-pointed stars.

The main and secondary borders, with their guard stripes, showing distinct Caucasian feeling, are typical of this group of rugs, and are in perfect harmony with the field. Very small in the main border can be detected the shaped symbol of religious significance, connected by origin with sun-worship, which occurs in many of the Central Asian rugs.

This carpet must, like all of its kind, have originally had broad web-ends, colored in consonance with the field.

These carpets of Southern Afghanistan are very plentiful, usually of good dyes and material, stout in texture and durable, but withal unattractive because of their too sombre coloring. Did these people but produce more carpets like the rarely fine example illustrated, there would be a readier market for their wares.

Source: The Connoisseur. An illustrated Magazine for Collectors. Edited by C. Reginald Grundy. Vol. LXII. (JANUARY—APRIL, 1922). London: Offices of The Connoisseur, AT I, Duke Street, St. James’s 1922.

Continuing

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.