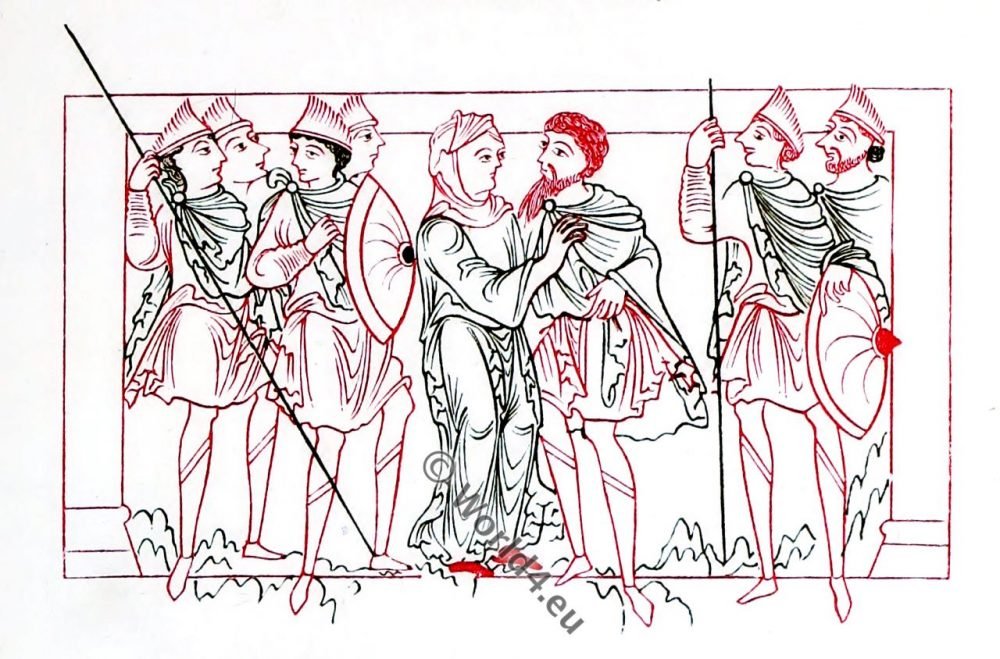

ILLUSTRATIONS OF PRUDENTIUS.

Aurelius Prudentius Clemens, (* 348; – after 405) was a late antique Christian poet.

Prudentius is the most important Christian poet of late antiquity, but his works can be dated only very imprecisely. His poetry is influenced by early Christian writers such as Tertullian and Ambrosius of Milan, as well as by the Bible and the martyrs. His most influential work, however, is the Psychomachia (“Battle of Souls”), the first allegorical poem of Latin literature; It was an inspiration and a source for medieval allegories. Prudentius was very popular in the Middle Ages. There are more than 300 manuscripts, the oldest one from the 6th century.

SIMILARLY illuminated manuscripts of the Psychomachia of Prudentius occur in several collections. The British Museum possesses one: another is found in the library of archbishop Tenison, in the parish of St. Martin in the Fields; and we believe that there is one in each of the Universities. They are all of about the same date.

The accompanying plate represents three of the drawings which illustrate the copy in the British Museum (MS. Cotton. Cleopat. C. VIII.), which appears to be a manuscript of about the ninth century.

They are good illustrations of the civil and military costume of that period. It may be observed that, as far as we can judge by the illuminations which have come down to us, the dress of our ancestors did not vary much during the Anglo-Saxon period.

Prudentius (a Christian poet who wrote at the beginning of the 5th century) was a favourite author among the Anglo-Saxons, and their love of allegorical writing made them prefer, above the rest of the poems, his Psychomachia, in which is described an imaginary battle between the Virtues and the Vices, the combatants being all clothed in human attributes. In the course of the engagement, Patience is attacked by Anger, whom she defeats by the resistance of her impenetrable armour,-

“Provida nam Virtus conserto adamante trilicem Induerat thoraca humeris, squamosaque ferri Texta per intortos commiserat undique nervos. Inde quieta manet Patientia, fortis ad omnes Telorum nimbos, et non penetrabile durans.”

After the defeat of Anger, Patience marches unhurt through the hostile ranks, accompanied by Job, who is represented by the bearded man in the picture, which belongs to the 162nd line of the poem,-

“Haec effata secat medias inpune cohortes Egregio comitata viro: nam proximus löb Haeserat invictae dura inter bella magistrae, Fronte severus adhuc, et multo vulnere anhelus.”

The second drawing refers to line 631 of the poem. The Virtues having obtained the victory, Peace makes her appearance, and drives away Fear, and Labour, and Force. This is the subject of the illumination in the middle of our plate,-

“His dictis curae emotae; metus, et labor, et vis, Et scelus, el placitae Fidei fraus inficiatrix, Depulsae vertere solum.”

Peace is described as being clad in a flowing vest, descending to her feet,-

“Vestis ad usque pedes deseendens defluit imos: Temperat et rapidum privata modestia gressum.”

The Virtues now approach, triumphantly, the citadel, where another deadly contest ensues between Concord and Discord. The approach to the city is the subject of the third drawing on our plate,-

“Sie expugnata Vitiorum gente, resultant Mystica duleimodis Virtutum carmina psalmis. Ventum erat ad fauces portae castrensis, ubi artum Liminis introitum bifori dant cardine claustra.” (Prudent. Psychom. v. 665.)

Our initial (or rather our two initials, for it represents two letters, S and I, a common occurrence in the earlier manuscripts) is taken from a fragment of a Latin Bible, preserved with some other fragments in the British Museum. The manuscript, from which it was stolen at the beginning of the last century, is in the Royal Library at Paris, and was written for Charles le Chauve. It is to be lamented that the fragment, which is in the Harleian Library, has not been restored to the manuscript.

Source: