Mount Hermon is a 2814 m high mountain massif in the Middle East in the border area between Lebanon, Israel and Syria. In the Arabic language, the mountain is called Jabal ash-Shaykh. The Hermon Mountains extend along the Syrian-Lebanese border for 25 kilometres in a southwest-northeast orientation. In the south, the mountain range ends on the Golan Heights annexed by Israel.

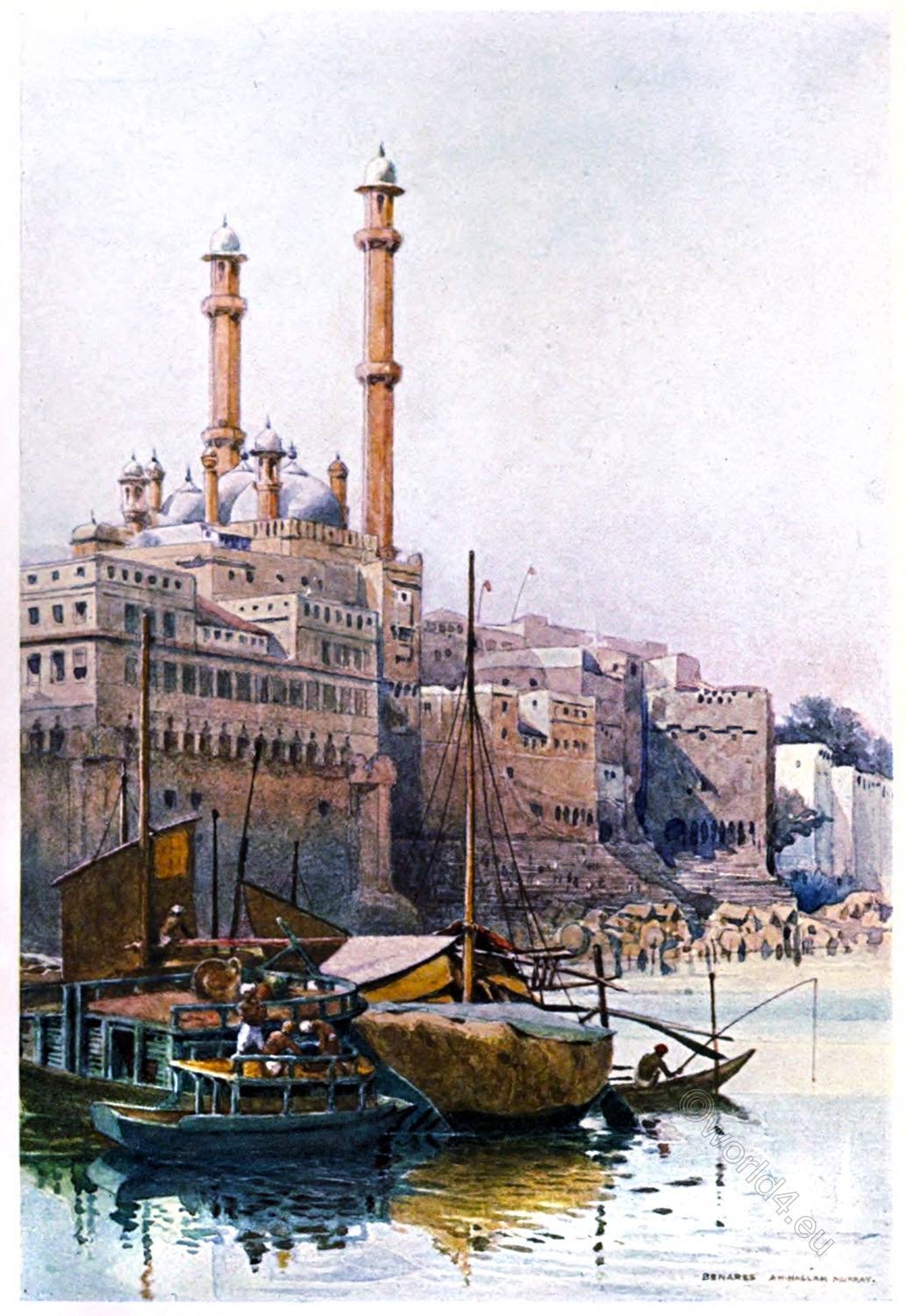

THE LAKE OF TIBERIAS, LOOKING TOWARDS HERMON

by David Roberts.

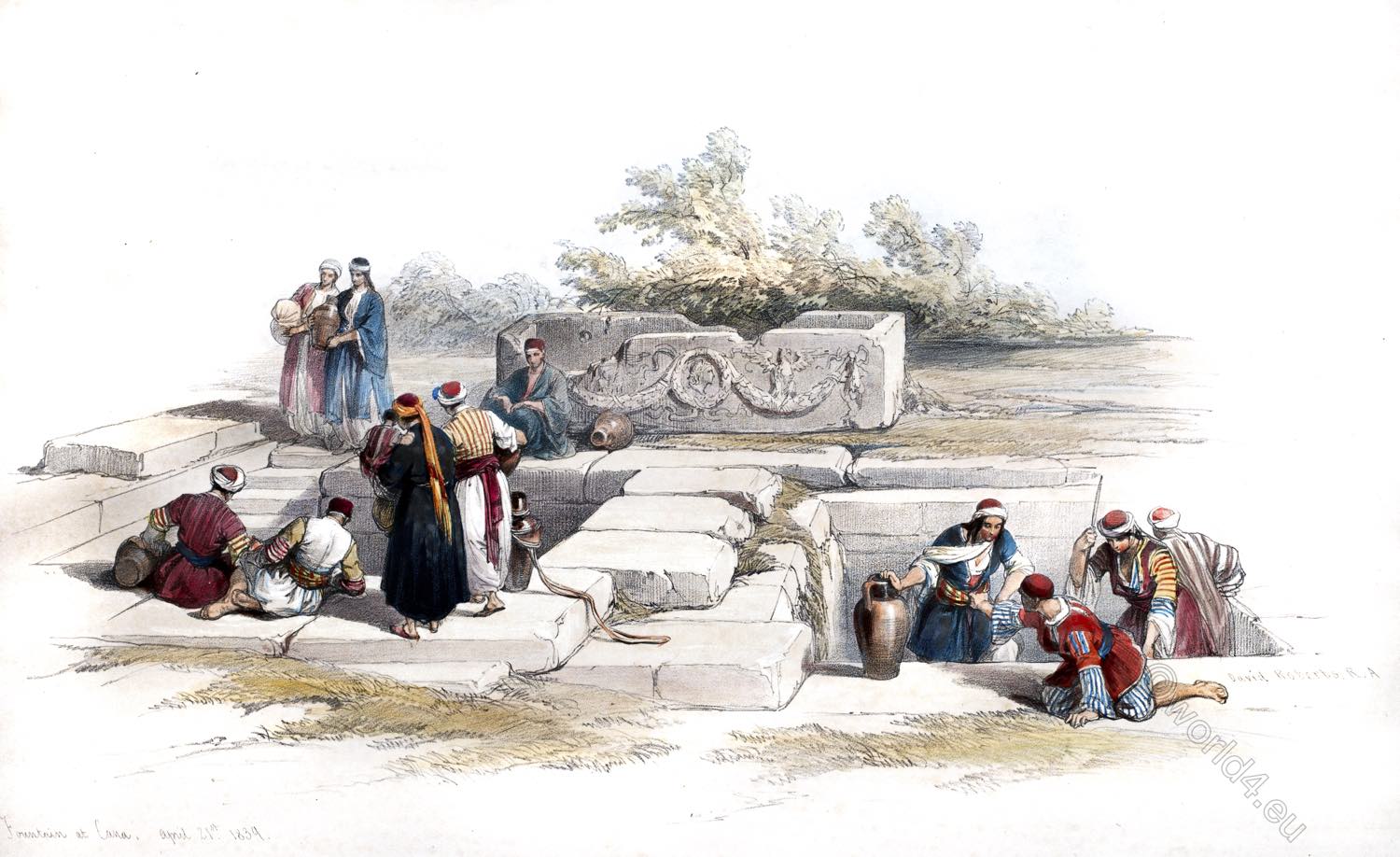

The ancient City of Tiberias, built by Herod Antipas, and named in honor of his patron, the Emperor Tiberius, has long since perished. With the mixture of violence and policy which characterized the Oriental governments, Herod compelled a population from the surrounding provinces to fill his City; adorned it with structures, of which the very fragments are stately; gave it peculiar privileges; and building a palace which was one of the wonders of the land, declared Tiberias the capital of Galilee. 1) The ruins in the Sketch are those of the modern City prostrated by the earthquake.

The view commands various sites, memorable from their connexion with Scripture. On the West coast lies El-Medgel, the site of Magdala, the City of Mary Magdalene; Capernaum, Chorazin, and Bethsaida, once lay on the same coast; and in the vicinity, more to the South, was the City of Tarichaea. On the East coast was the scene of the great miracle, the feeding of the four thousand; and in the horizon is the majestic Hermon, 10,000 feet above the Mediterranean.

The Rabbins held that the former City stood on the site of Rakkath, while Jerome records a tradition that it was once Chinnereth; 2) but, leaving those laborious triflings to their natural obscurity, it is evident that the original Tiberias occupied a site farther to the north. There the ground is still strewed with fragments of noble architecture,—baths, temples, and perhaps theatres; giving full proof of a Capital raised with the lavish grandeur of a Herodian City.

In the great, final war, which extinguished Judah as a nation, and commenced the longest calamity of the most illustrious and unhappy race of mankind, Tiberias escaped the general destruction. Submitting to the authority of Vespasian, without waiting to be subdued by his arms, the City retained its population, and, probably, its privileges.

In the national havoc, it even acquired the additional wealth and honors of a City of Refuge. It had a coinage of its own, exhibiting the effigies of several of the Emperors, down to Antoninus Pius. It appears to have peculiarly attracted Imperial notice, for Hadrian, though pressed with the cares of the Roman world, commenced the rebuilding of a temple, or palace, which had been burnt in an insurrection. 3)

But the history of this beautiful City has a still higher claim on human recollection, as the last retreat of Jewish literature. On the fall of Jerusalem, and the final expulsion of the Jews from the central province, the chief surviving portion of the state, the rank, the wealth, and the learning, were suffered to take shelter within the walls of Tiberias. In the second century, a Sanhedrim was formed there, and the broken people made their last attempt to form a semblance of established government. 4)

The two great Hebraists, Buxtorf and Lightfoot, have given the history of the School of Tiberias, more interesting than the details of massacre, or the description of ruins. The protection of the City drew the principal scholars from the cells and mountains where they had concealed themselves from the habitual severities of Rome.

Under the presidency of Rabbi Judah Hakkodesh the School flourished, and acquired the acknowledged title of the Capital of Jewish learning. The first natural enterprise of such a School was the collection of the ancient interpretations and traditions of the Law; and those were embodied by Rabbi Judah in the Mishna (about A.D. 220). In the third century, Rabbi Jochanan compiled the Gemara, a supplement to the Mishna (about A.D. 270), now known as the Jerusalem Talmud.

In the sixth century, the Babylonian Jews also compiled a Gemara, named the Talmud of Babylon, now more esteemed by the Jews. But the School of Tiberias is said also to have produced the Masora, or Canon for preserving the purity of the text in the Old Testament,—a labour whose value, however the subject of controversy, is admitted to be incontrovertible.

The civil history of Tiberias is the common recapitulation of Eastern sieges and slaughters. Fortified by Justinian, it fell successively into the hands of the Saracens, the Crusaders, Saladin, the Syrians, 5) and the Turks. The French invasion brought Tiberias into European notice once more (a.d. 1799). On their retreat it sank into its old obscurity, and must wait another change, of good or evil fortune, to be known.

1) John, vi. 23 ; xxi. 1. Joseph. Antiq. xviii. 2, 3. Bell. Jud. ii. 9, 4.

2) Josh. xix. 35. Hieron. Coram, in Ezech. xlviii. 21.

3) Epiphan. ad Hseret. i. 12.

4) Lightfoot, Ap. ii. 141. Buxtorf, Tiberias, 10, &c.

5) Niebuhr, Reise. iii. Volney, Voyage, c. xxv.

Source: The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, & Nubia, by David Roberts, George Croly, William Brockedon. London: Lithographed, printed and published by Day & Son, lithographers to the Queen. Cate Street, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, 1855.

Continuing