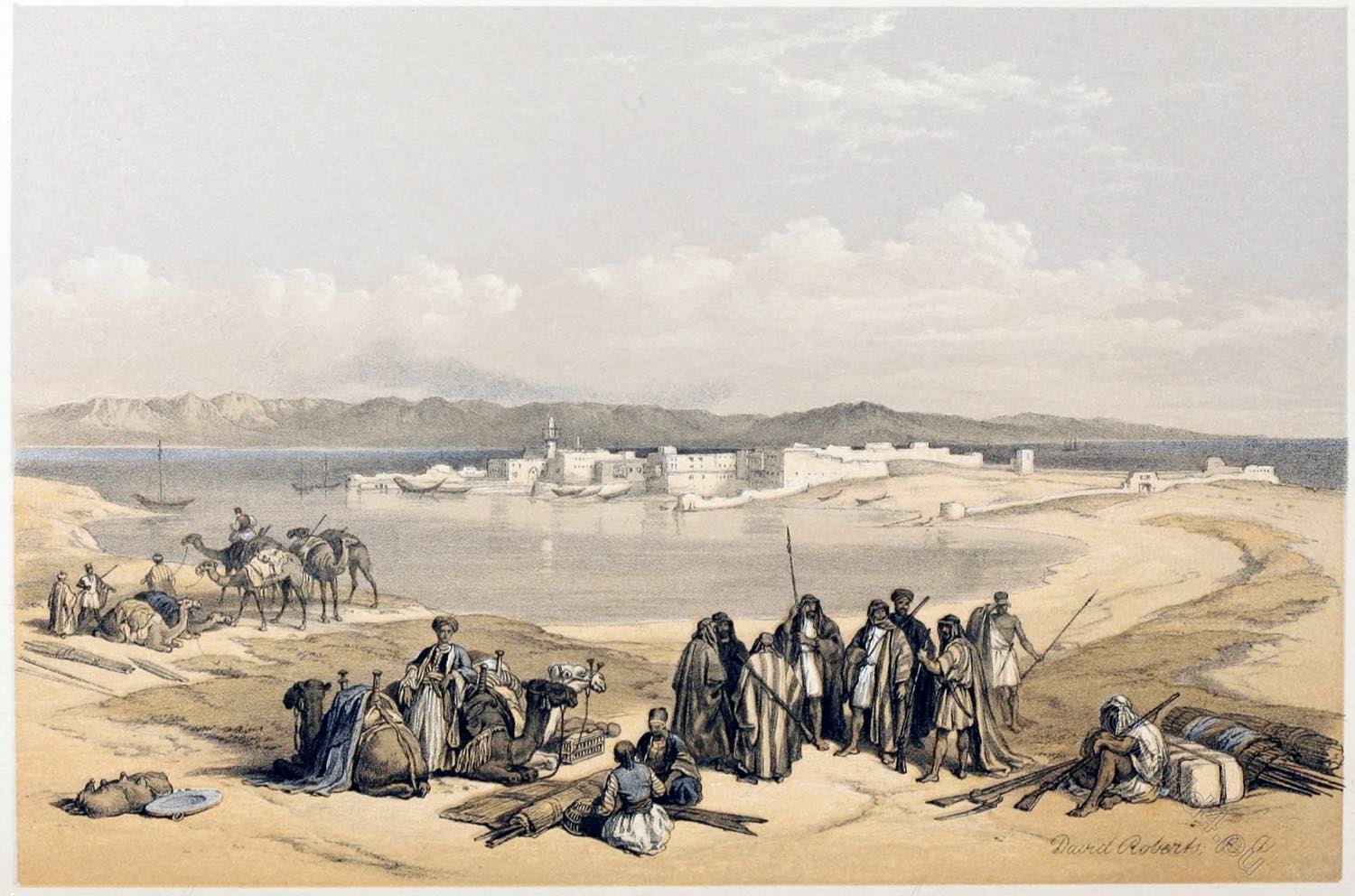

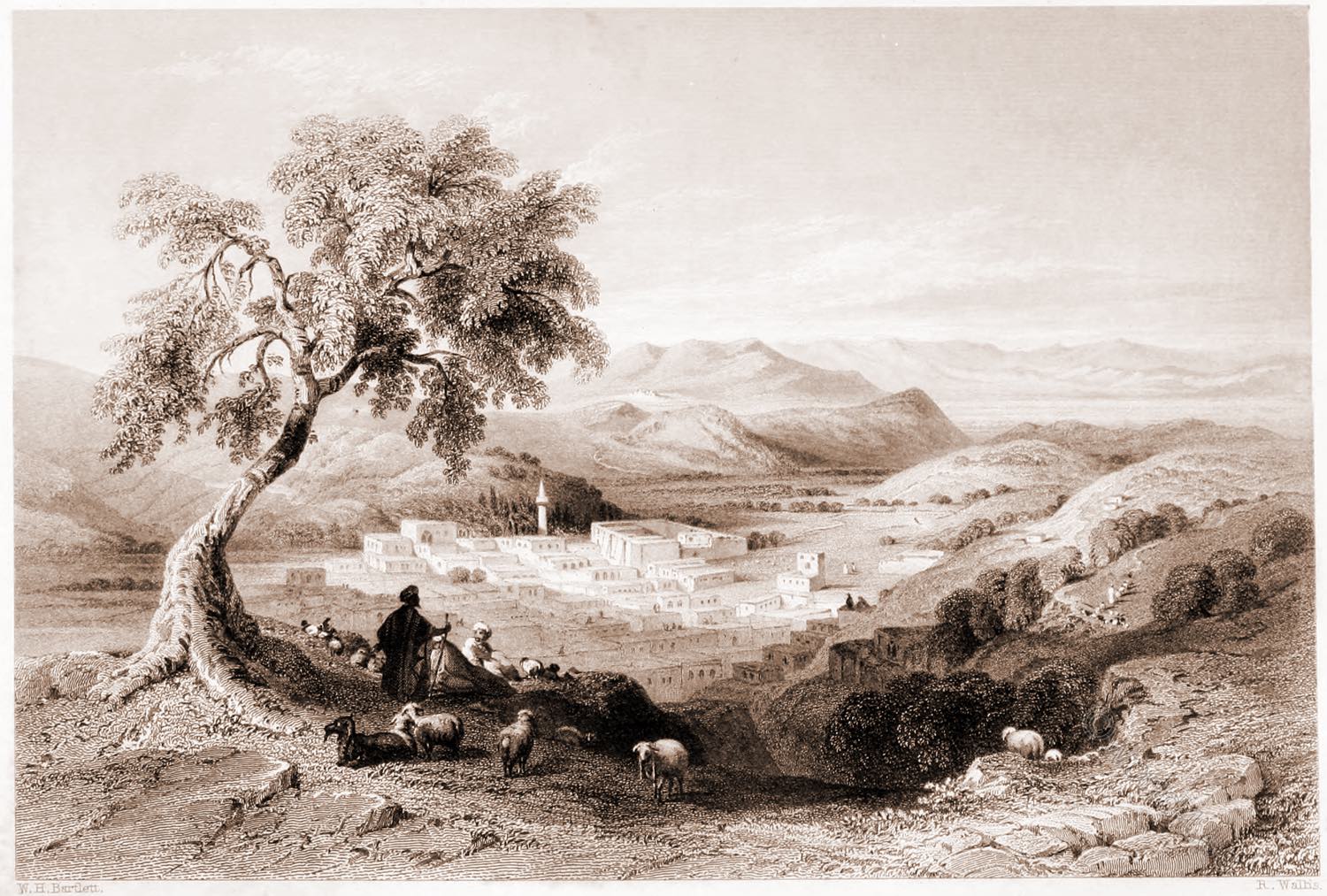

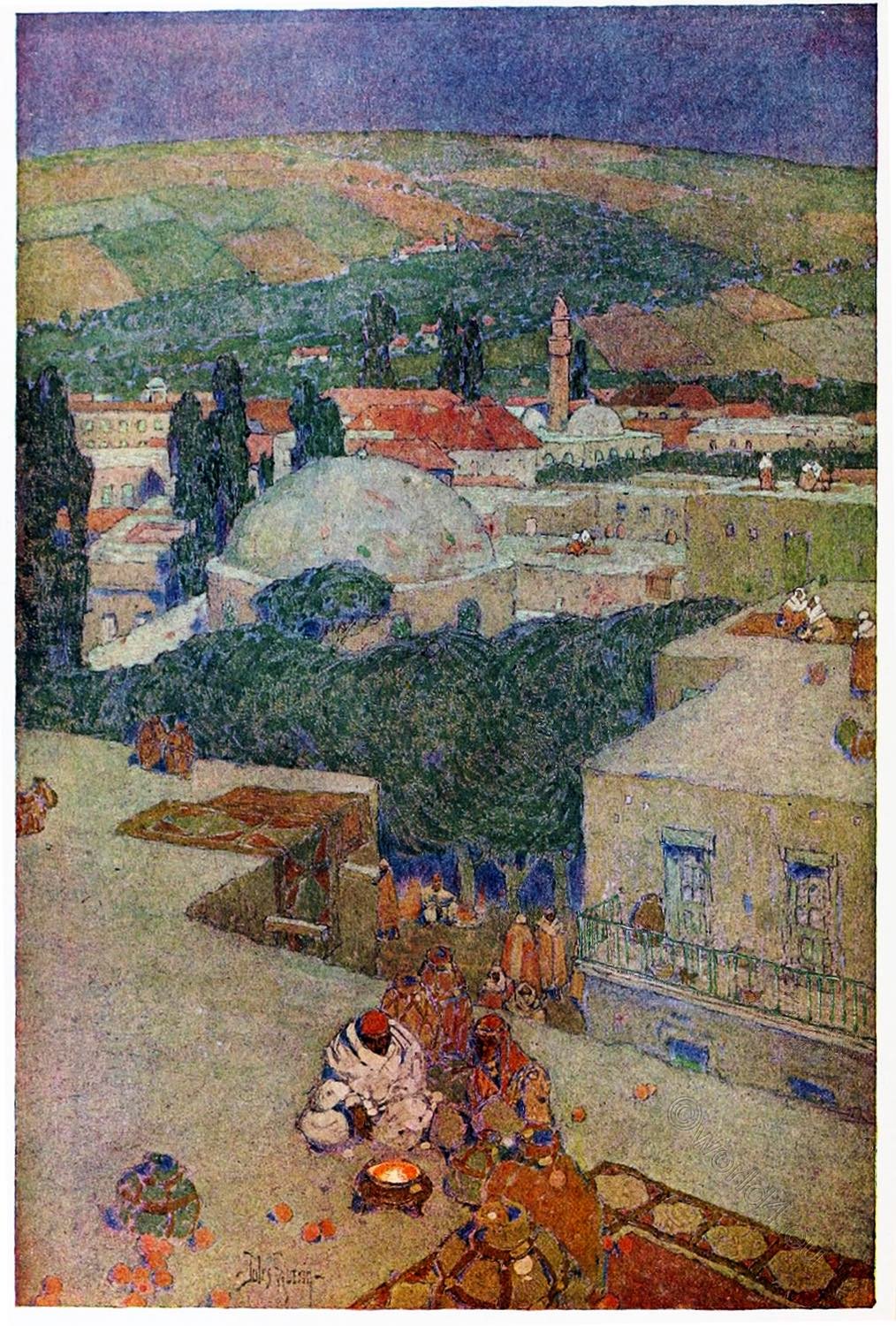

GENERAL VIEW OF NAZARETH

by David Roberts.

The man must be insensible to the highest recollections of our being who can look on Nazareth without reverence for the might and mercy that once dwelt there. Generations pass away, and the noblest monuments of the hand of man follow them; but the hills, the valley, and the stream exist, on which the eye of the Lord of all gazed; the soil on which His sacred footsteps trod; the magnificent landscape in the midst of which He lived, working miracles, subduing the stubborn hearts of the multitude, and pronouncing to the Earth that “The Kingdom was at hand.”

The view from the hill above Nazareth is one of the most striking in Palestine. Beneath it lies the chief part of the noble Plain of Esdraelon. To the left is seen the summit of Mount Tabor, over intervening hills; with portions of the Little Hermon, Gilboa, and the opposite mountains of Samaria. The long line of Carmel is visible, stretching to the sea, with the Convent of Elias on its northern promontory, and the town of Jaifa at its foot. In the West spreads the Mediterranean, always lovely, and reflecting every colour of the morning and evening sky. On the North opens out a verdant and beautiful plain, now called El-Buttauf (Lower Galilee). Beyond this plain, long ridges of hills, extending East and West, are overtopped by the mountains of Safed, crowned with that city. Towards the right is “a sea of hills and mountains,” backed by the still higher ridge beyond the Lake of Tiberias, and on the N.E. by “the majestic Hermon, with its icy crown.” 1)

The town of Nazareth (in Arabic En-Nasirah) lies on the western side of a narrow, oblong basin, extending from S.S.W. to N.N.E. twenty minutes in length and ten in breadth. The houses stand on the lower slope of the western hill, which rises steep and high above them: the dwellings are in general well built, and of stone; they have flat, terraced roofs, without the domes so common hi Southern Palestine. The population is about three thousand souls, of which the Mohammedans compose 120 families; the rest are Greek, Latin, and Maronite. 2)

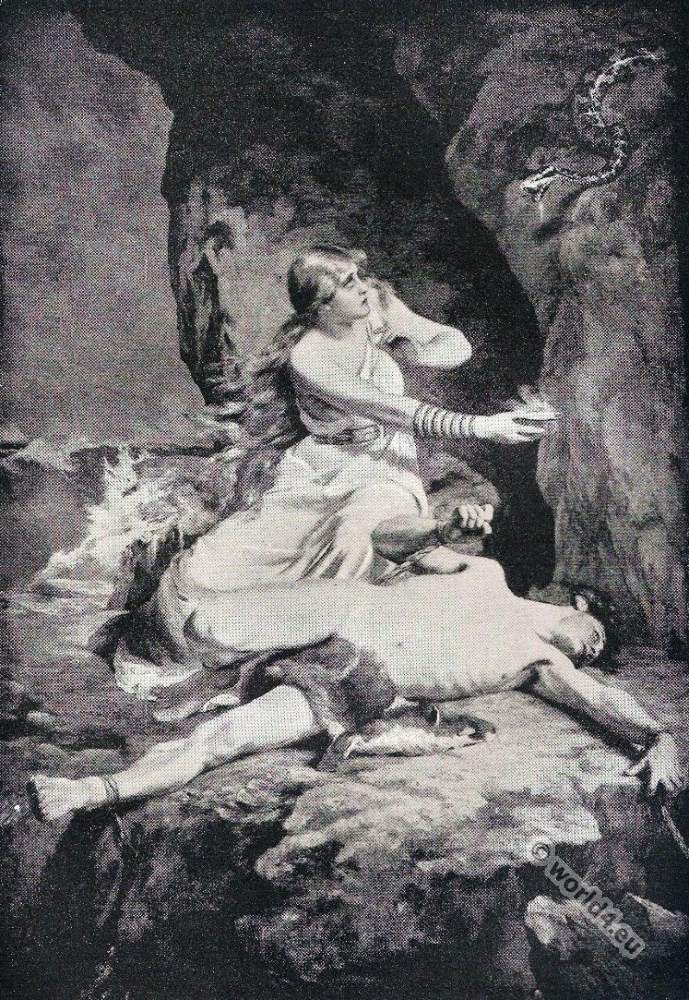

The Monks have been as active, and as unfortunate, as usual, in assigning Scriptural events to localities in Nazareth and the adjoining country. The “Mount of Precipitation” — “the brow of the hill,” to which the people led Jesus, “that they might cast him down headlong,” as narrated by St. Luke—is fixed by them at a precipice overlooking the Plain of Esdraelon, and nearly two miles from the town. But the improbability that a violent populace would have been content to lead the object of their indignation to so great a distance, when they might have cast him down from any of the surrounding cliffs, has induced the monks to move their imaginary Nazareth to the same hill.

As no mention of miracle is made by the Evangelist in the rescue of our Lord, it has been doubted whether any divine interposition was wrought. Yet it is difficult to conceive by what human means He eonld have escaped from the hands of a people who had been infuriated to the degree of forcing Him to the edge of the precipice. “He, passing through the midst of them, went his way,” seems the language of innate power. We hear of no argument or remonstrance from our Lord. He allows the popular rage to act, up to the precise moment when it appeared irresistible; and then convinces His enemies at once of His divine authority and of their crime, by calmly returning through them, now consciously unable to arrest His steps, and leaving them behind, in astonishment and awe.

It is also observable, that the twofold clearance of the Temple, at the beginning and the close of our Lord’s ministry, is an example of silence on the subject of miracle, though both must have been acts of miraculous will; for what individual means could have driven out the whole multitude of money-changers, and the sturdy peasantry and cattle-dealers of Judea, from the court of the Temple? or what other rebuker would not have been trampled or slain by that furious multitude?

1) Biblical Researches, iii. 183. 2) Narrative of a Mission to the Jews, ii. 72.

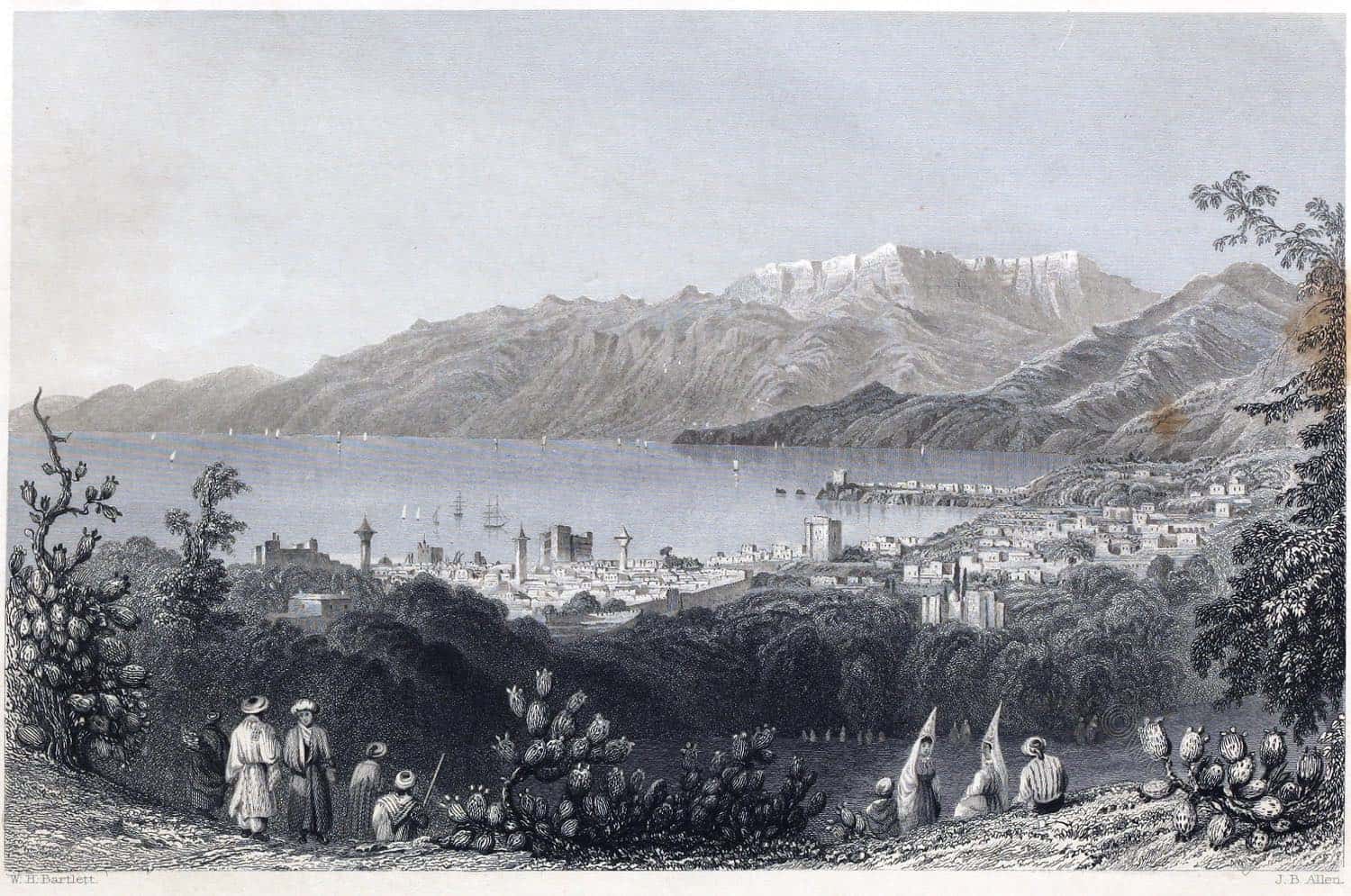

NAZARETH.

by Thomas Hartwell Horne

Drawn by J. M. W. Turner, from a Sketch by C. Barrt, Esq.

Among the various places in Palestine which were honored by the presence of Jesus Christ, Nazareth, where he spent the greater part of his youth, is eminently distinguished. (Matt. ii. 23. Luke ii. 51, 52.)

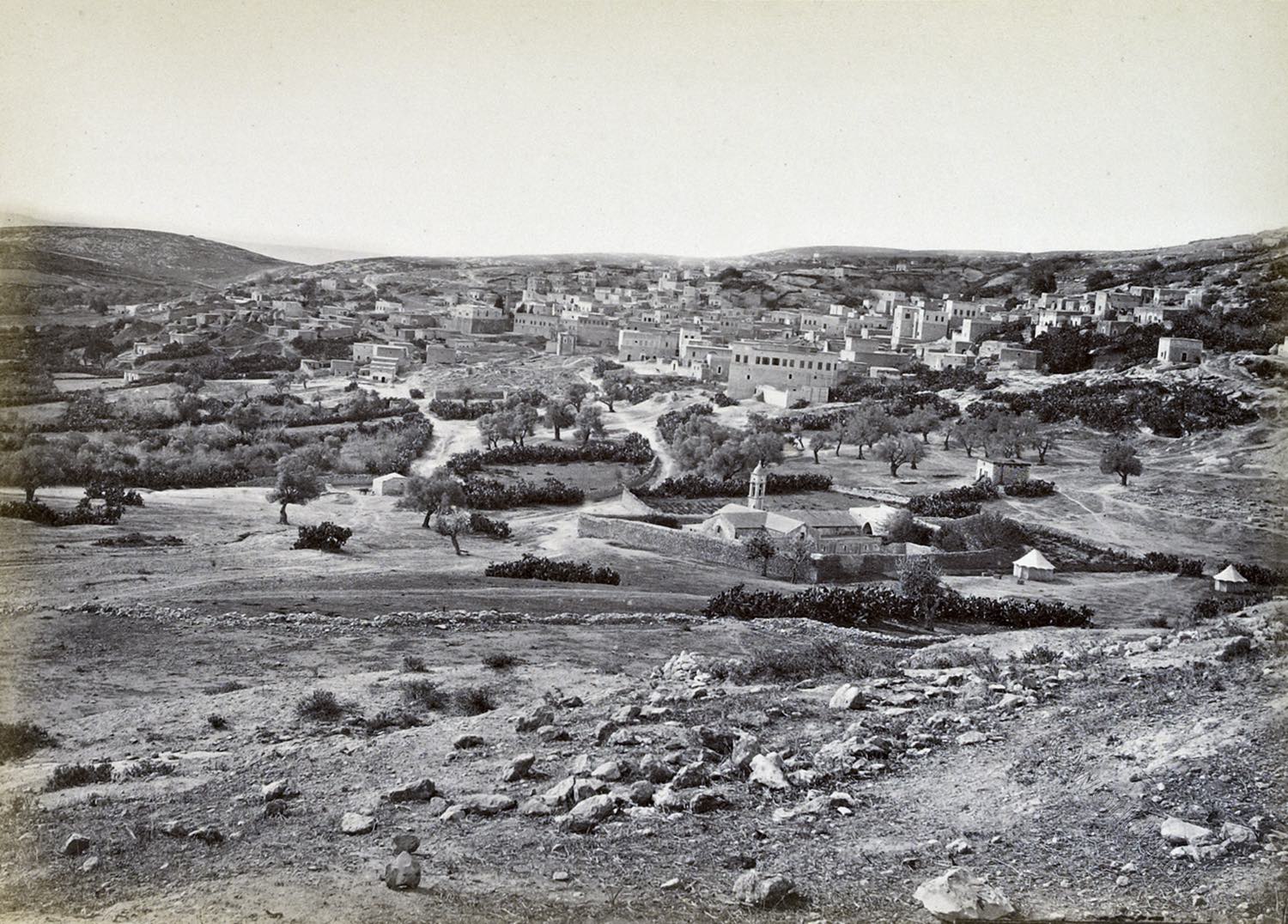

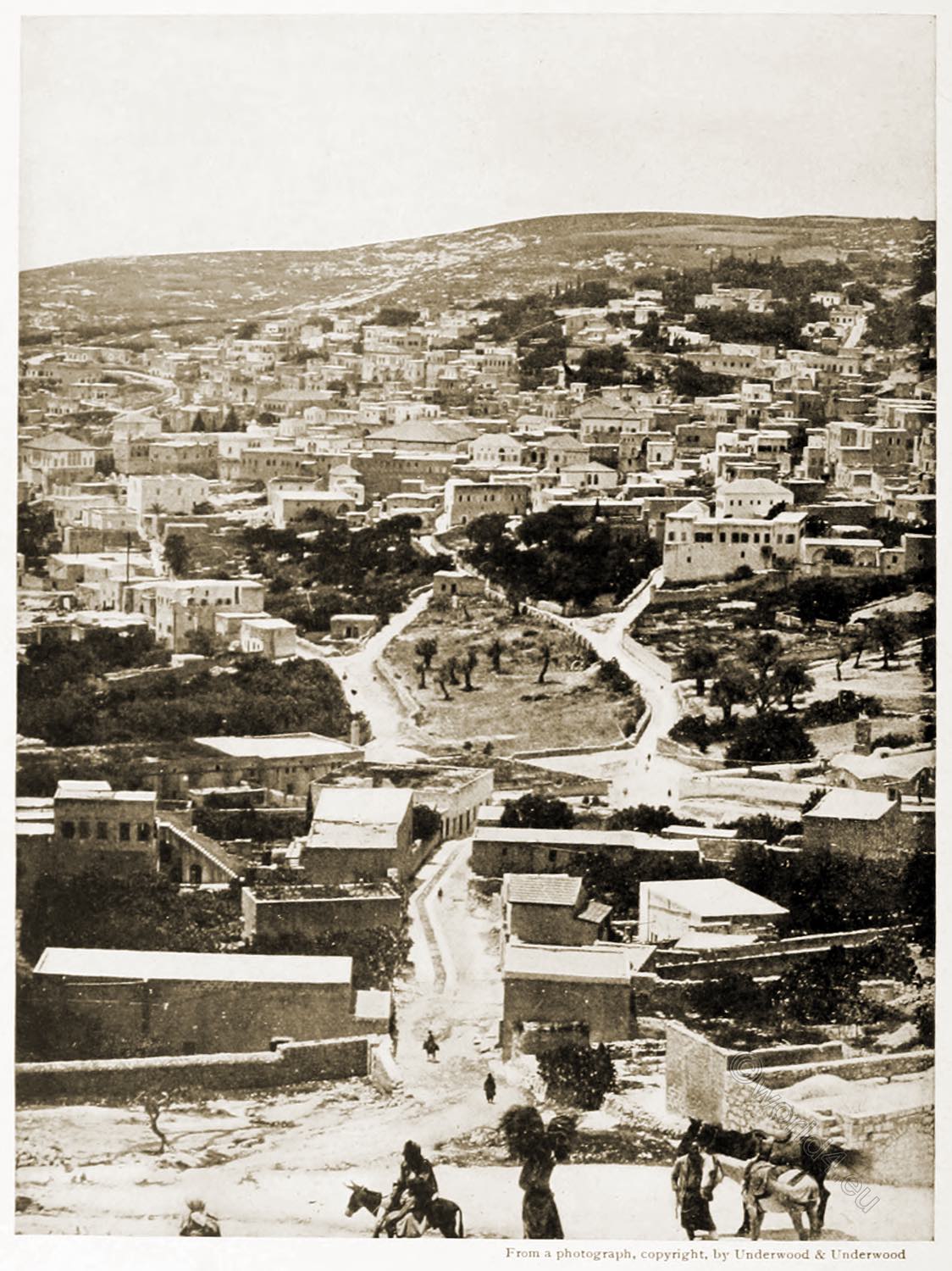

Nazareth is beautifully situated; but, though it is termed a city in the sacred Volume, it is now an inconsiderable village; and the houses are as much marked by poverty as the inhabitants. The vale in which it lies resembles a circular basin encompassed by mountains: it seems as if fifteen mountains met to form an inclosure for this delightful spot; they rise round it like the edge of a shell to guard it from intrusion. It abounds in fig trees, small gardens, and hedges of the prickly pear; and the dense rich grass affords an abundant pasture.

The village stands on the west side of the valley. The houses are small, flat-roofed, and built of a light porous stone. The bazaars are small square rooms, having only a doorway; and a gutter runs through the middle of the narrow streets. In the centre of the town stands one mosque, the minaret of which daily pro- claims that Jesus of Nazareth is not the dominant master here.

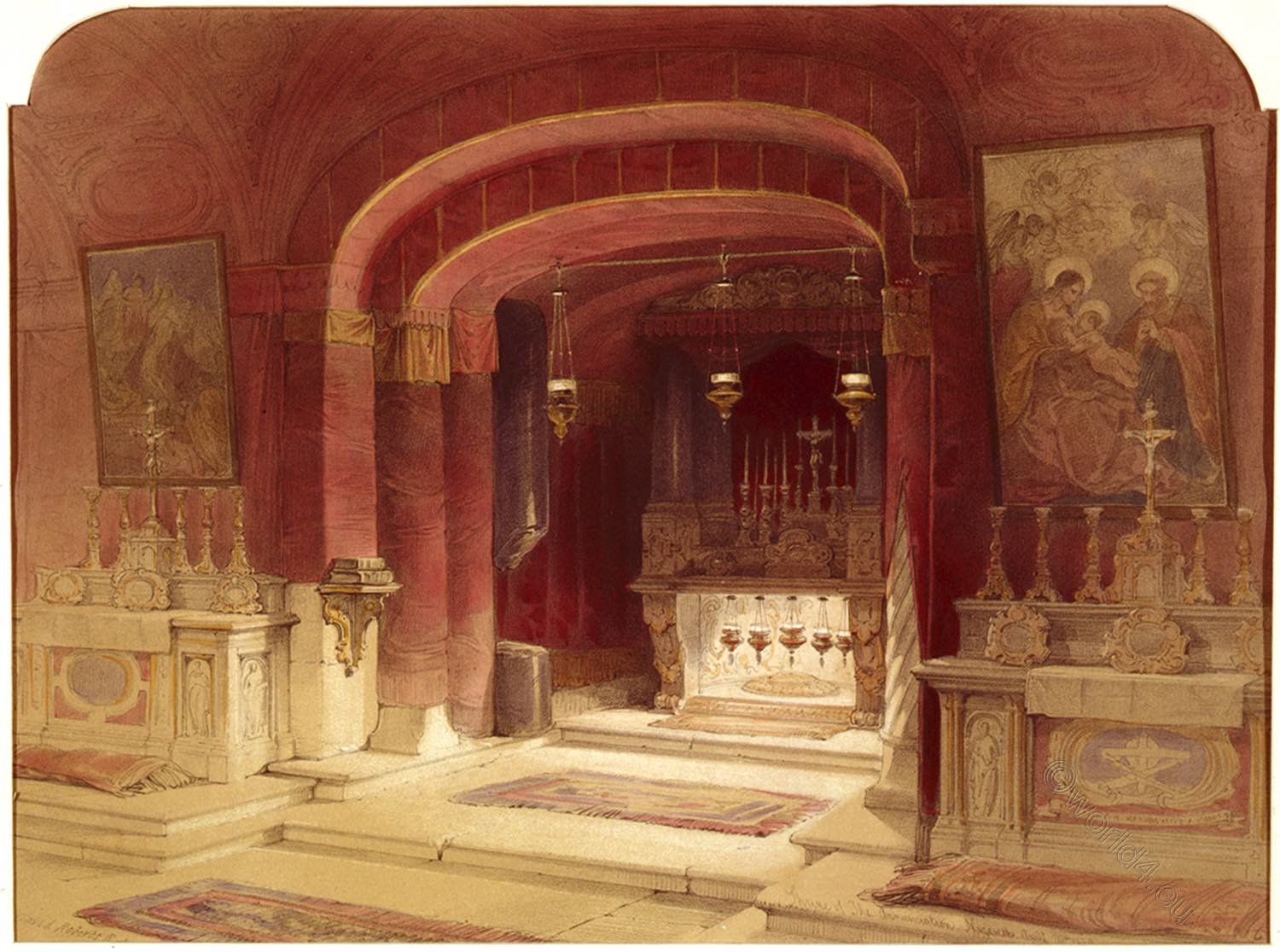

The Latin convent stands at the east end of the village, and is built upon the high ground just where the rocky surface joins the valley. Its church, which is called the ” Church of the Incarnation,” is erected on the supposed spot where the angel Gabriel saluted the Virgin Mary with the joyful tidings related in Luke i. 28—38. It resembles the figure of a cross : that part of it which stands for the tree of the cross is fourteen paces long and six broad, and runs into the grotto which is said to have been the house of Joseph and Mary. The transverse part of it is nine paces in length and four in width, and is built across the mouth of the cave. Just at the section of these divisions are erected two granite pillars, two feet in diameter, and about three feet distant from each other.

According to one tradition, they were intended to represent the dimensions of the angel who delivered the heavenly message: but another account represents them to stand on the very places where the angel and the blessed Virgin severally stood at the time of the annunciation. The innermost column, which is intended to represent the Virgin Mary, has been made the subject of a pretended miracle. The column has been broken through above the pedestal, and the fractured portion is separated, yet the upper part of the column does not fall, but remains suspended in the air. It has evidently no support below, and the monk who shows it protests that it has none above: the inference, which it is wished that the credulous visitor should deduce, is, that it is a daily and perpetual miracle.

The fact, however, is, that the capital and a piece of the shaft have been fastened to the roof of the grotto; and what is shown for the lower fragment of the same pillar resting upon the earth, according to Dr. Clarke, is not of the same substance, but of cipolino marble. Up stairs, above the church of the incarnation, there are exhibited to travelers another grotto, called the ” Virgin Mary’s kitchen,” and a black smoked place in the corner, which is called her chimney.

Near the convent is shown the “workshop of Joseph:” it is now a small chapel, perfectly modern. Over the altar is a representation of him with the implements of his trade, and holding the infant Jesus by the hand, as if instructing him in his mechanical employment.

The population of Nazareth is estimated, by different travelers, at fifteen hundred or two thousand, about six hundred of whom are Christians. No Jews are permitted to reside here. This village is now called Nassera.

Rae Wilson’s Travels, vol. i. pp. 387—397. Dr. Richardson’s Travels, vol. ii. pp.434—441. Dr. Clarke’s Travels, vol. iv. p. 170. Madox’s Excursions in the Holy Land, &c. vol. ii. pp. 206. 252.

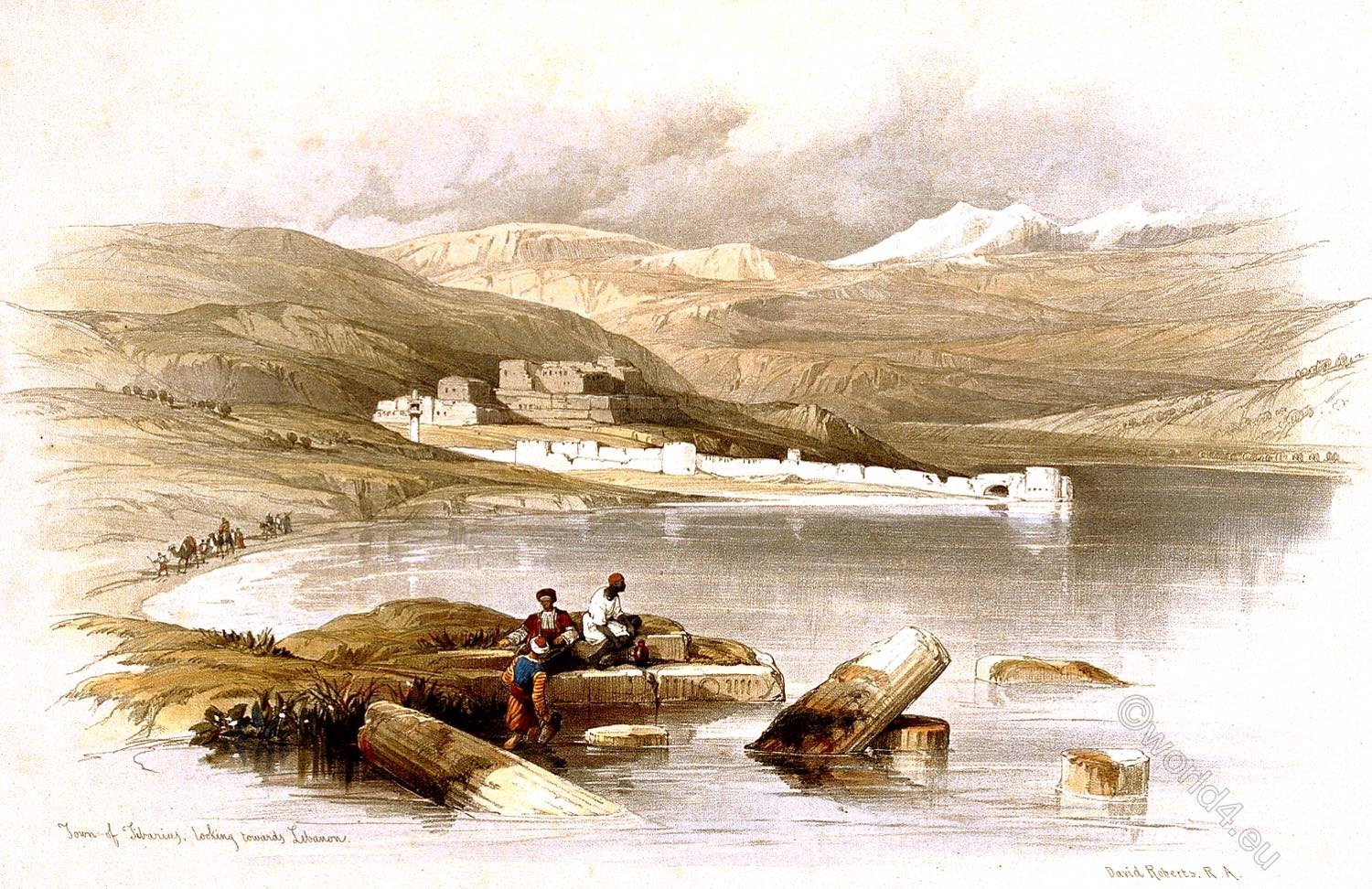

NAZARETH (Plate II.), WITH THE MOUNT OF PRECIPITATION.

by Thomas Hartwell Horne

Drawn by A. W. Callcott, from a Sketch made on the spot by the Rev. R. M. Master.

This view exhibits the village of Nazareth (of which a general account has been given in Part II. of this work), together with the amphitheatre of mountains which rise majestically around it.

Not far distant from the house of Joseph, mentioned in the description already referred to, is shown the synagogue where our Savior preached the sermon related in Luke iv. 18—27-; and also the precipice, from which the monks of the Latin convent affirm that he leaped down, in order to escape the rage of his townsmen, who were offended at his application of the sacred text.

“All they in the synagogue, when they heard these things, were filled with wrath, and rose up, and thrust him out of the city; and led him to the brow of the hill whereon their city was built, that they might cast him down headlong. But he, passing through the midst of them, went his way.” (Luke iv. 28—30.)

The Mount of Precipitation, as it is now called, is about a mile and a half distant from Nazareth, according to Dr. Richardson, but two miles according to the observations made by Mr. Buckingham and the Rev. W. Jowett; though Dr. E. D. Clarke maintains that the words of the evangelist explicitly prove the situation of the ancient city to have been precisely that which is occupied by the modern village. Mr. Jowett, however, has (we conceive) clearly shown that the Mount of Precipitation could not be immediately contiguous to Nazareth. This village, it will be observed, is situated in a little sloping vale or dell on the side, and nearly extends to the foot of a hill, which, though not very lofty, is rather steep and overhanging.

“The eye naturally wanders over its summit, in quest of some point from which it might probably be, that the men of this place endeavoured to cast our Saviour down (Luke iv. 29.); but in vain: no rock adapted to such an object appears.

“At the foot of the hill is a modest simple plain, surrounded by low hills, reaching in length nearl)r a mile ; in breadth, near the city, a hundred and fifty yards; but further on, about four hundred yards. On this plain there are a few olive-trees and fig-trees, sufficient, or rather scarcely sufficient, to make the spot picturesque.

“Then follows a ravine, which gradually grows deeper and narrower, till, after walking about another mile, you find yourself in an immense chasm with steep rocks on either side, from whence you behold, as it were beneath your feet, and before you, the noble Plain of Esdraelon. Nothing can be finer than the apparently-immeasurable prospect of this plain, bounded to the south by the mountains of Samaria. The elevation of the hills on which the spectator stands in this ravine is very great ; and the whole scene, when we saw it, was clothed in the most rich mountain-blue colour that can be conceived. At this spot, on the right hand of the ravine, is shown the rock to which the men of Nazareth are supposed to have con- ducted our Lord, for the purpose of throwing him down.

“With the Testament in our hands, we endeavored to examine the probabilities of the spot; and I confess there is nothing in it which excites a scruple of incredulity in my mind. The rock here is perpendicular for about fifty feet, down which space it would be easy to hurl a person who should be unawares brought to the summit; and his perishing would be a very certain consequence. That the spot might beat a considerable distance from the city is an idea not inconsistent with St. Luke’s account; for the expression ‘thrusting’ Jesus’ out of the city, and leading him to the brow of the hill on which their city was built,’ gives fair scope for imagining, that, in their rage and debate, the Nazarenes might, without originally intending his murder, press upon him for a considerable distance after they had quitted the synagogue.

“The distance, as already noticed, from modern Nazareth to this spot is scarcely two miles— space which, in the fury of persecution, might soon be passed over. Or should this appear too considerable, it is by no means certain but that Nazareth may at that time have extended through the principal part of the plain, which lies before the modern town: in this case, the distance passed over might not exceed a mile.

“It remains only to note the expression—’ the brow of the hill, on which their city was built’: this, according to the modern aspect of the spot, would seem to be the hill north of the town, on the lower slope of which the town is built but I apprehend the word ‘hill’ to have in this, as it has in very many other passages of Scripture, a much larger sense; denoting sometimes a range of mountains, and in some instances a whole mountainous district. In all these casss the singular word ‘Hill,’ ‘Gebel,’ is used according to the idiom of the language of this country.

“Thus, ‘Gebel Carmyl,’ or Mount Carmel, is a range of mountains: ‘Gebel Libnan,’ or Mount Lebanon, is a mountainous district of more than fifty miles in length: ‘Gebel ez-Zeitun,’ the Mount of Olives, is certainly a considerable tract of mountainous country. And thus any person, coming from Jerusalem and entering on the Plain of Esdraelon, would, if asking the name of that bold line of mountains which bounds the north side of the plain, be informed that it was ‘Gebel Nasra,’ the Hill of Nazareth; though, in English, we should call them the Mountains of Nazareth. Now the spot shown as illustrating Luke iv. 29. is, in fact, on the very brow of this lofty ridge of mountains: in comparison of which, the hill upon which the modern town is built is but a gentle eminence.”

This intelligent traveller, therefore, concludes that this mountain may be the real scene where our Divine Prophet, Jesus, experienced so great a dishonor from the men of his own country and of his own kindred.

In a valley near Nazareth is a fountain which bears the name of the Virgin Mary, and where the women are seen passing to and fro with pitchers on their heads as in days of old. It is justly remarked that, if there be a spot throughout the Holy Land which was more particularly honored by the presence of Mary, we may consider this to be the place because the situation of a copious spring is not liable to change, and because the custom of repairing thither to draw water has been continued among the female inhabitants of Nazareth from the earliest period of

its history.

Dr. Richardson’s Travels, vol. ii. p. 441. Buckingham’s Travels in Palestine, vol. ii. p. 315. Jowett’s Christian Researches in Syria, pp. 165—167. Dr. Russell’s Palestine, p. 317.

Source:

- The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, & Nubia, by David Roberts, George Croly, William Brockedon. London: Lithographed, printed and published by Day & Son, lithographers to the Queen. Cate Street, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, 1855.

- The Christian in Palestine; or, Scenes of sacred history, historical and descriptive by Henry Stebbing (1799-1883). London: G. Virtue 1847.

- The Holy Land by Robert Smythe Hichens, (1864-1950). Paintings by Jules Guerin. New York: The Century co. 1910.

- Souvenirs d’Orient: album pittoresque des sites, villes et ruines les plus remarquables de la Terre-Sainte, par Félix Bonfils (1831-1885). A Alais (Gard): Chez l’auteur, 1878.

- Landscape Illustrations of the Bible, consisting of views of the most remarkable places mentioned in the Old and New Testaments, from original sketches taken on the spot by Thomas Hartwell Horne (1780-1862), engraved by William Finden (1787-1852), Edward Francis Finden (1791-1857), Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851), Bartolomé de las Casas (1474-1566). London: John Murray: Sold also by Charles Tilt, 1836.

Continuing

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.