Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kosciuszko (1746-1817) was a Polish military engineer who became a Polish national hero in the Russo-Polish War of 1792 and especially as the leader of the 1794 uprising against the partitioning powers of Russia and Prussia, named after him.

Between 1776 and 1783, Kosciuszko also fought on the American side in the American War of Independence. He represented the ideals of the Enlightenment and supported the worldwide movement to abolish slavery. The status of a national hero is attributed to him not only in Poland but also in Belarus, the United States and partly in Lithuania.

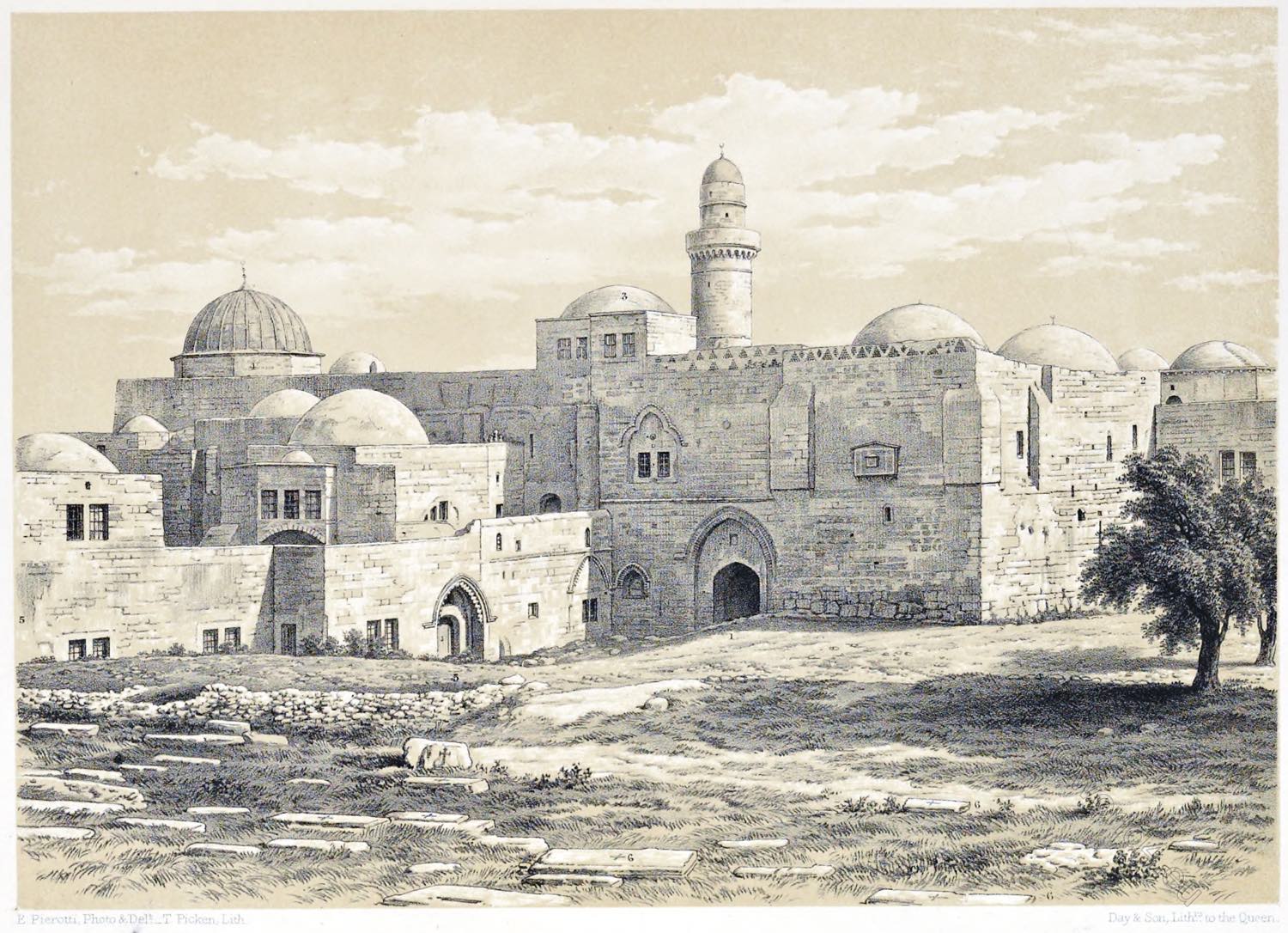

The Tomb of Kosciusko.

KOSCIUSKO’S MONUMENT.

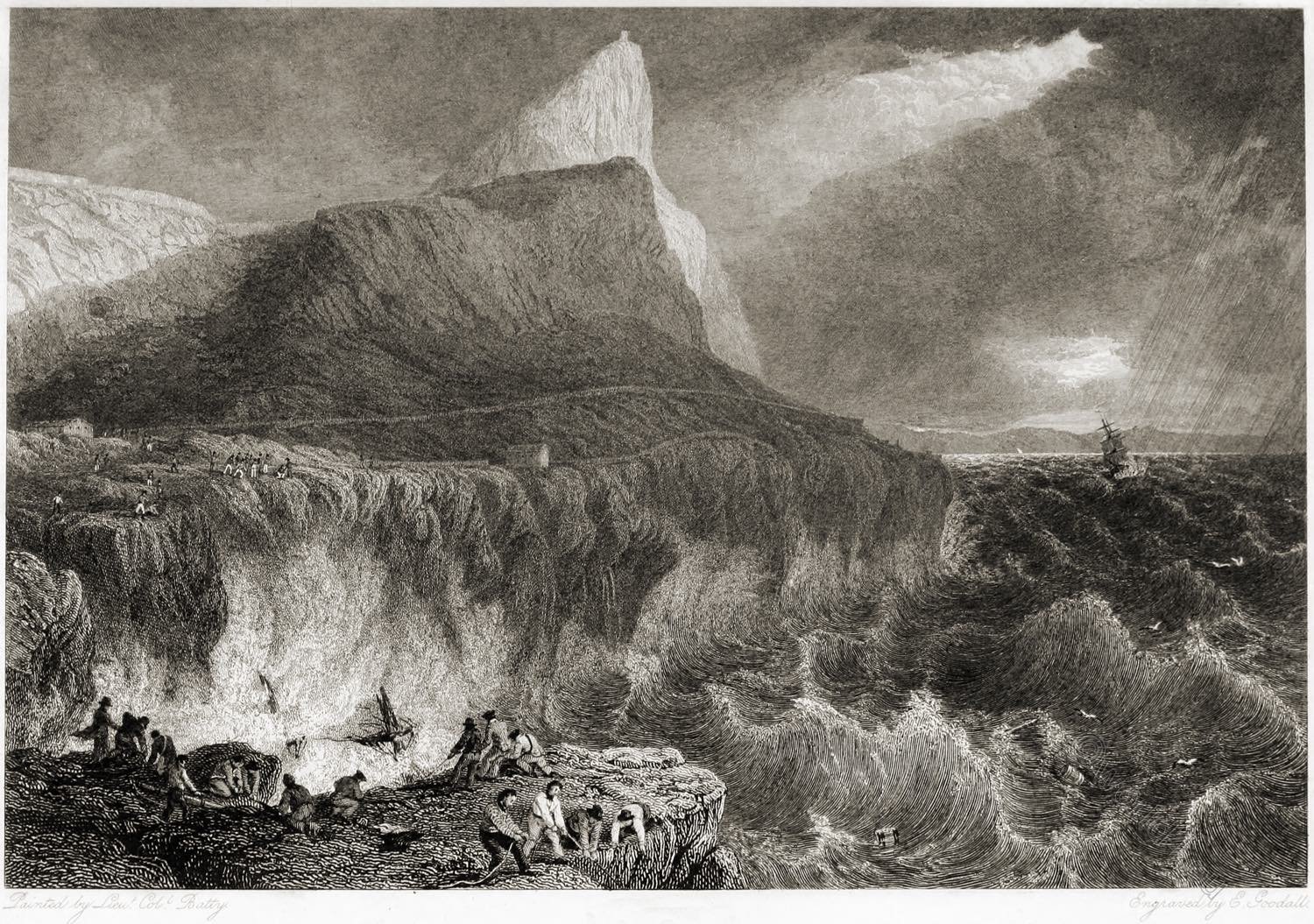

A pretty marble shaft stands on the edge of the broad highland esplanade of West Point, overlooking the most beautiful scene on the most beautiful river of our country. It commemorates the virtues of Kosciusko, who, during his second sojourn in America, lived at West Point, and cultivated his little garden, near the site of this tribute to his memory.

Kosciusko’s first laurels were gained in this country under Washington. He was educated in the military school at Warsaw, whence he was sent, as one of four, to complete his education at Paris. On his return to Poland, he had a commission given him, but, being refused promotion, he determined to come to America, and join the colonies in their struggle for independence. With letters from Dr. Franklin to General Washington, he presented himself to the great patriot, and was immediately appointed his aid-de-camp, and later he received the appointment to the engineers, with the rank of colonel.

At the close of the war, having distinguished himself by his courage and skill, he returned to Poland, was appointed major-general in the army of the diet, and served as general of division under the younger Poniatowski.

Finding, however, his efforts for freedom paralysed by the weakness or treachery of others, he gave in his resignation, and went into retirement at Leipsie. He was still there in 1793, when the Polish army and people gave signs of being in readiness for insurrection. All eyes were turned towards Kosciusko, who was at once chosen for their leader, and messengers were sent to him from Warsaw to acquaint him with the schemes and wishes of his compatriots. In compliance with the invitation, he proceeded towards the frontiers of Poland; but apprehensive of compromising the safety of those with whom he acted, he was about to defer his enterprise, and set off for Italy.

He was fortunately persuaded to return, and, arriving at Cracow at the very time when the Polish garrison had expelled the Russian troops, he was chosen generalissimo, with all the power of a Roman dictator. He immediately published an act, authorising insurrection against the foreign authorities, and proceeded to support Colonel Madalinski, who was pursued by the Russians. Having joined that officer, they gained their first victory, defeating the enemy with inferior numbers. His army now increased to nine thousand men, the insurrection extended to Warsaw, and in a few days the Russians were driven from that palatinate. He obtained some advantage over the enemy in one more contest, but the king of Prussia arriving to the assistance of the Russians, he was exposed to great personal danger, and suffered a defeat.

From this period he waged a disadvantageous warfare against superior force, and at last at Maczienice (or Maniejornice), fifty miles from Warsaw, an overwhelming Russian force completely defeated Kosciusko. He fell from his horse wounded, saying Finis Poloniae, and was made prisoner.

Kosciusko was sent to Russia, and confined in a fortress near Saint Petersburg, where he was kept till the accession of Paul I (1754-1801, Tsar of Russia and Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp). This monarch, through real or affected admiration for the character of the great man, released him, and presented him with his sword: “I have no longer occasion for a sword, since I have no longer a country,” answered Kosciusko.

In 1797 he once more took his departure for the United States, where he was received with honour and warm welcome by the grateful people whose liberty he had aided to achieve. He was granted a pension by the government, and elected to the society of the Cincinnati. He returned to Europe the following year, bought an estate near Fontainebleau, and lived there till 1814.

He removed again to Switzerland, and established himself at Soleure, where he died, in consequence of a fall with his horse over a precipice near Vevay. Among the last acts of his life, were the emancipation of the slaves on his own estate in Poland, and a bequest for the emancipation and education of slaves in Virginia. Kosciusko was never married. His body was removed to Cracow, and deposited with great state in the tomb of the kings beneath the cathedral.

The oldest officers were his bearers; two beautiful young girls with wreathes of oak leaves and cypress followed, and then came a long procession of the general staff, senate, clergy, and people. Count Wodsiki delivered a funeral oration on the hill of Wavel, and a prelate delivered an eloquent address in the church. The senate decreed that a lofty mound should be erected on the heights of Bronislawad.

For three years men of every age and class toiled gratuitously at this work, and at last the Mogila Kosziuszki, the mound of Kosciusko, was raised to the height of 3000 feet! A serpentine path leads to the top, from which there is a noble view of the Vistula, and of the ancient city of the Polish kings. The small monument at West Point has less pretension, but it is the exponent of as deep a debt of gratitude, and of as grateful and universal honour to his memory.

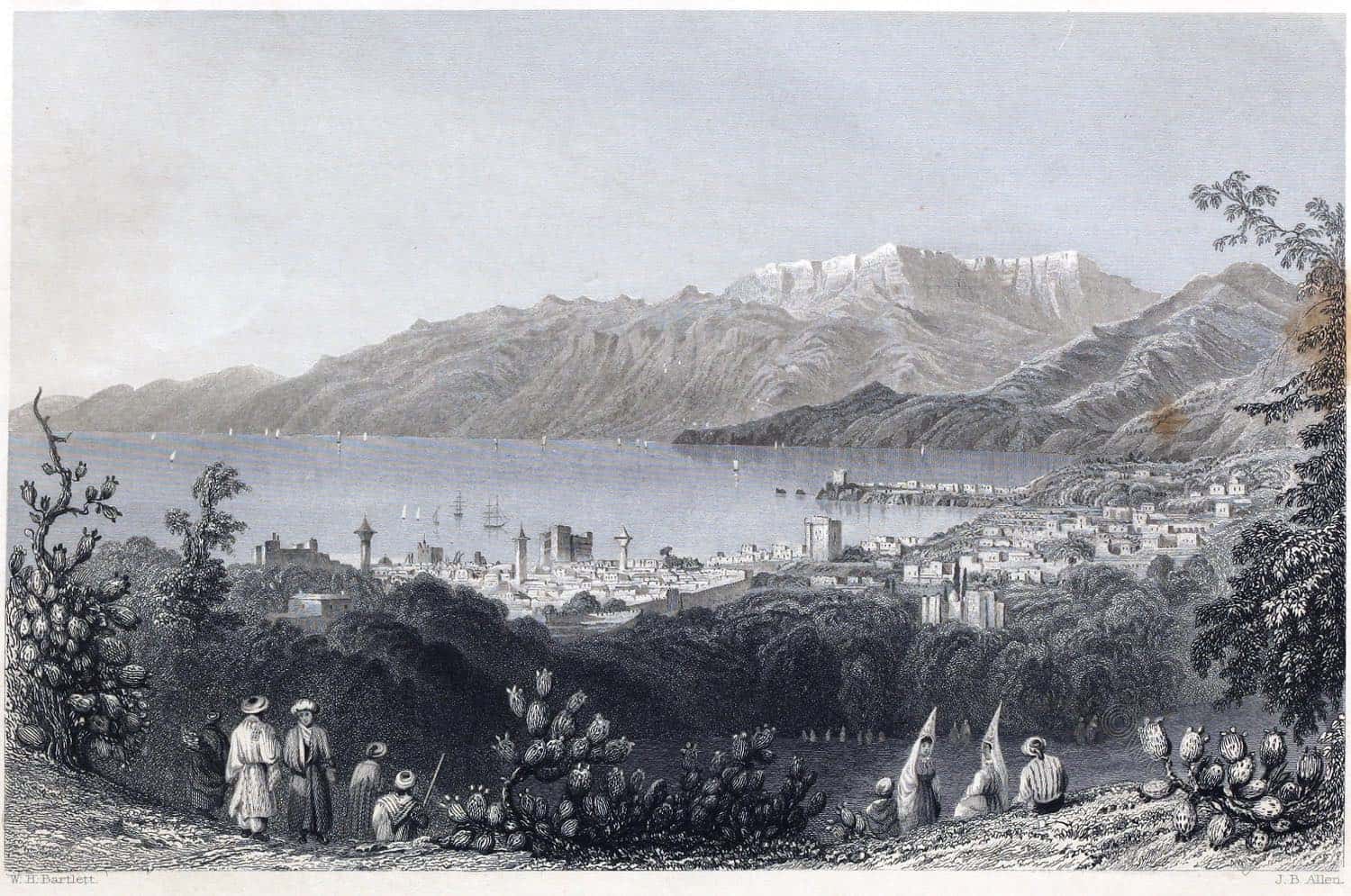

Source: American Scenery; or, Land, Lake, and River Illustrations of Transatlantic Nature. From Drawings by W. H. Bartlett. Engraved by R. Wallis, J. Cousen, Willmore, Brandard, Adlard, Richardson, &c. The Literary Department by Nathaniel Parker Willis, Esq. London: George Virtue 26, Ivy Lane. 1840. Vol. 1.

Continuing

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.